As the statue of Marduk was carried through the city of Babylon, every man, woman, and child stopped to pay homage to the figure. Although it neither moved nor spoke, the people considered this sculpture to be the living embodiment of their most important god. The Babylonians, like other Mesopotamian societies, were a polytheistic culture that worshipped several gods and goddesses. The collective pantheon of ancient Mesopotamian gods consisted of local gods who acted as patrons for individual cities as well as interregional deities who were worshipped by multiple cultures. Some deities became so prominent that they were worshipped throughout the Cradle of Civilization. As a result, they are considered the most important gods of Mesopotamia.

1. An/Anu: The Supreme Mesopotamian God

An, referred to by the Akkadians as “Anu”, was the Mesopotamian god of the sky. Similar to the sky gods of other ancient mythologies, such as Zeus, An was considered the supreme god of their pantheon and the father of many other Mesopotamian deities. An was also listed as one of the three gods involved with creating the universe, and he was widely revered as the ultimate authority figure in Mesopotamian culture. Although An was worshipped throughout Cradle of Civilization, he was said to have a particular connection to the Sumerian city of Uruk and was often referred to as its patron deity.

As the supreme deity and ultimate authority figure, the Mesopotamians relied on An to maintain their physical and social world. An was said to contain the entire universe within himself, and he also controlled the laws by which the universe was governed. Correspondingly, the Mesopotamians considered An to be the supreme authority over their administrative structure and the final word on legal disputes of any kind. As a result, kings would support their right to rule by claiming that they held An’s favor. Similarly, Mesopotamian administrators would legitimize their policies by asserting that the laws were supported by An.

Legal documents, such as the Code of Hammurabi, would enforce compliance by asserting that those who broke their laws would incur the wrath of An. In comparison to other deities, An was relatively detached from day-to-day happenings in Mesopotamian society. However, he was undoubtedly one of the most important deities in their pantheon.

2. Enki/Ea: Wisest of the Mesopotamian Gods

Enki, also known as Ea, was the Mesopotamian god of water and wisdom. Enki was said to reside in the Abzu, which the Mesopotamians believed was a freshwater ocean located beneath the earth that was the source of all streams, rivers, and lakes. One of Enki’s primary roles was as a creator deity, as he was one of the three Mesopotamian gods involved in making the universe. Enki was also credited with making the first humans out of clay and he was believed to have created the Tigris and Euphrates rivers out of his semen. In addition to being the god of water and wisdom, Enki was associated with trickery, magic, and fertility. As was the case with many Mesopotamian gods, Enki was closely associated with specific cities and was believed to be the patron of the city Eridu.

As agricultural societies, the Mesopotamians depended on water for their continued survival. As a deity associated with the production of water, Enki was considered essential to the life of the people and to the continuity of their cities. In addition, Enki was also considered a protector of humanity who would defend mortals from the destructive aggression of other deities. As the god of wisdom, Enki was often called upon by individuals who needed advice or by administrators and kings seeking the wisest course of action.

In addition to maintaining their physical and mental wellbeing, the Mesopotamians also relied on Enki for their spiritual health. In relation to his association with magic, Enki was credited with developing rituals for exercising demons and expelling evil. Enki then taught these practices to priests, who the Mesopotamians depended on to protect them and maintain their spiritual wellbeing. As such, Enki fulfilled a myriad of roles which made him integral to the Mesopotamians.

3. Enlil: The Great Mountain

Enlil was one of the most prominent gods in the Mesopotamian pantheon, second only to the supreme god An. Enlil was primarily the Mesopotamian god of air, earth, and storms. However, he was also believed to have control over the fates and his commands were unalterable. He was listed with An and Enki as one of the three gods involved in the creation of the universe. However, the Mesopotamians viewed Enlil as a god of both destruction and creation, as they believed that this deity was primarily responsible for natural disasters and catastrophes. In the Epic of Gilgamesh, Enlil is responsible for sending the Great Flood that almost wipes out humanity. Although Enlil’s primary temple was located in the city of Nippur, he was worshipped throughout the Fertile Crescent and had temples in many politically prominent cities, such as Assur and Babylon.

Enlil’s importance is reflected through his titles, such as “The Great Mountain” and “King of All Lands”. Because Enlil was both creator and destroyer, the Mesopotamians attributed all aspects of their existence to him. As a deity with unalterable authority and control over fate, events that happened on earth were attributed to the will of Enlil. As such, this deity was central to the Mesopotamian worldview. In addition to his cosmological significance, Enlil was also important to the political structuring of Mesopotamian societies. As an authoritative deity, Enlil was said to confer kingship on ordained rulers. Mesopotamian kings who wanted to legitimize their reign did so by claiming the blessing of Enlil.

4. Marduk: King of the Gods

Scholars believe that Marduk may have originated as an agricultural deity who was worshipped as the patron of the city of Babylon. As the Babylonian Empire rose as a political power in the region, Marduk became an increasingly prominent deity in the Mesopotamian pantheon.

Over time, Marduk would take on the roles of many other gods, such as An and Enlil, until he became one of the most important and powerful Mesopotamian gods in their history. At the height of his worship, Marduk was considered the king of the gods and the supreme authority who controlled all things “in heaven and earth”. As a result, Marduk was also credited with helping form the universe and bring order to the physical world by defeating the goddess Tiamat and her army of primordial chaos. However, a central role of Marduk’s was to maintain universal balance so he was viewed as a god of both creation and destruction.

As a god who helped create the universe and bring order to the natural world, Marduk was central to the cosmology of later Mesopotamians. Being a god of both creation and destruction, Marduk was also associated with calamities that occurred, such as natural disasters. These aspects of Marduk, coupled with his supreme authority, would have likely made his influence seem all-encompassing to the Mesopotamians.

Along with this, Marduk’s status as a supreme god made him important to the political structure of Babylonian Mesopotamia. In order to be accepted as a ruler, every king of the Babylonian Empire had to receive Marduk’s approval through a ritual in which they grasped the hands of Marduk’s statue. The Babylonians were so dependent on Marduk that when a statue of the god was taken from the city during a war, the Babylonians could not practice their religious rituals until the statue had been returned.

5. Ishtar/Inanna: Queen of the Universe

Ishtar, also known as Inanna, was the Mesopotamian goddess of love, sex, and war. Corresponding to primary roles, Ishtar was associated with fertility and politics. However, Ishtar’s sphere of influence extended beyond her main aspects, as she was also perceived as a divine administrator of justice. Along with this, this goddess was worshipped as a type of liminal deity who could influence transitional periods in life. In Mesopotamian mythology, Ishtar often acted as an instigator who would challenge the authority of other gods or initiate confrontations that would trigger significant events.

Mesopotamian texts recorded that Ishtar was the twin sister of Shamash and the younger sister of Ereshkigal, the goddess of the underworld. This goddess was universally worshiped throughout the Fertile Crescent and had temples in every major city. Her cult center, however, was in the Sumerian city of Uruk.

Corresponding to her wide sphere of influence, Ishtar was involved in almost every aspect of Mesopotamian life. As the goddess of love and sex, Mesopotamians would go to the temple of Ishtar to be married or to seek her help with conceiving a child. As a liminal goddess who often challenged social norms, the Mesopotamians believed that Ishtar enabled her followers to cross entrenched social boundaries, such as gender roles and class-based limitations.

Similarly, Ishtar had significant influence over the politics of Mesopotamia as kings would legitimize their rule by ceremonially “marrying” themselves to the goddess. Ishtar also had a role in the more violent side of Mesopotamian politics as the goddess of war. In particular, rulers would often call upon her for victory in battle. Due to her influence over secular and political life in Mesopotamia, Ishtar continued to be one of the most important deities throughout Mesopotamian history even as other gods lost their status in the pantheon.

6. Shamash/Utu: The All-Seeing

Shamash, also referred to as Utu, was the Mesopotamian god of the sun. Similar to the Greek god Apollo, it was believed that Shamash pulled the sun across the sky each day. Because of this, the Mesopotamians believed that Shamash saw everything that happened on the ground, and so this god also became associated with truth and justice. As a result, Shamash was the primary god of justice in the Mesopotamian pantheon as well. Shamash was the twin brother of Ishtar, the goddess of love and war. Although Shamash was worshipped throughout Mesopotamia, his primary temples were located in the cities of Sippar and Larsa.

Unlike some of the other important deities in the Mesopotamian pantheon, Shamash was not credited with creating the universe. Rather, his significance came from his role in maintaining the physical world by ensuring that the sun rose each day. As an agricultural society, the Mesopotamians were dependent on the sun for growing their crops. While this alone secured Shamash’s place as an important deity, his role as a god of justice was of equal significance to the social and political structure of Mesopotamian culture.

Shamash was credited with bringing the rule of law to humans, and was said to be the ultimate judge of both mortals and other Mesopotamian deities. Shamash was also involved with enforcing legal contracts, treaties, and business transactions, Some scholars believe that the Code of Hammurabi, one of the oldest legal codes in human history, was meant to be a contract between King Hammurabi and the god Shamash.

7. Nanna/Sin: God of the Moon

Nanna was the Mesopotamian god of the moon. Referred to as “Sin” in some texts, this god was one of the oldest deities in their pantheon. In addition to his primary role as a lunar deity, Nanna was believed to have the ability to see the future and to control the destinies of mortals. As a result, this god was heavily associated with magic and rituals. In particular, Nanna was linked to divination, astrology, and omens.

Nanna is listed as the son of Enlil and is married to Ningal, the goddess of fertility and reeds. Some Mesopotamian texts list Nanna as the father of Ereshkigal, Ishtar, and Shamash. As one of the oldest deities in their pantheon, Nanna was worshipped throughout Mesopotamian history and his cult was widespread in the Fertile Crescent. Nanna’s cult was centered in the Sumerian city of Ur, and the Great Ziggurat in this city was dedicated to him.

Similar to Shamash, Nanna’s importance lay in his role in maintaining the physical world. Just as the Mesopotamians believed that they would not have the sun without Shamash, they relied on Nanna for the continued presence of the moon. Mesopotamians also depended on the moon to keep track of time and their annual calendars were divided by lunar phases. Nanna was also important to the religion of Mesopotamian societies, as divination and the observation of omens were central to their belief systems. Because religion was often integrated into Mesopotamian politics, Nanna also had influence over issuing verdicts in legal disputes and was often called upon to “illuminate” the truth.

The Influence of the Mesopotamian Gods

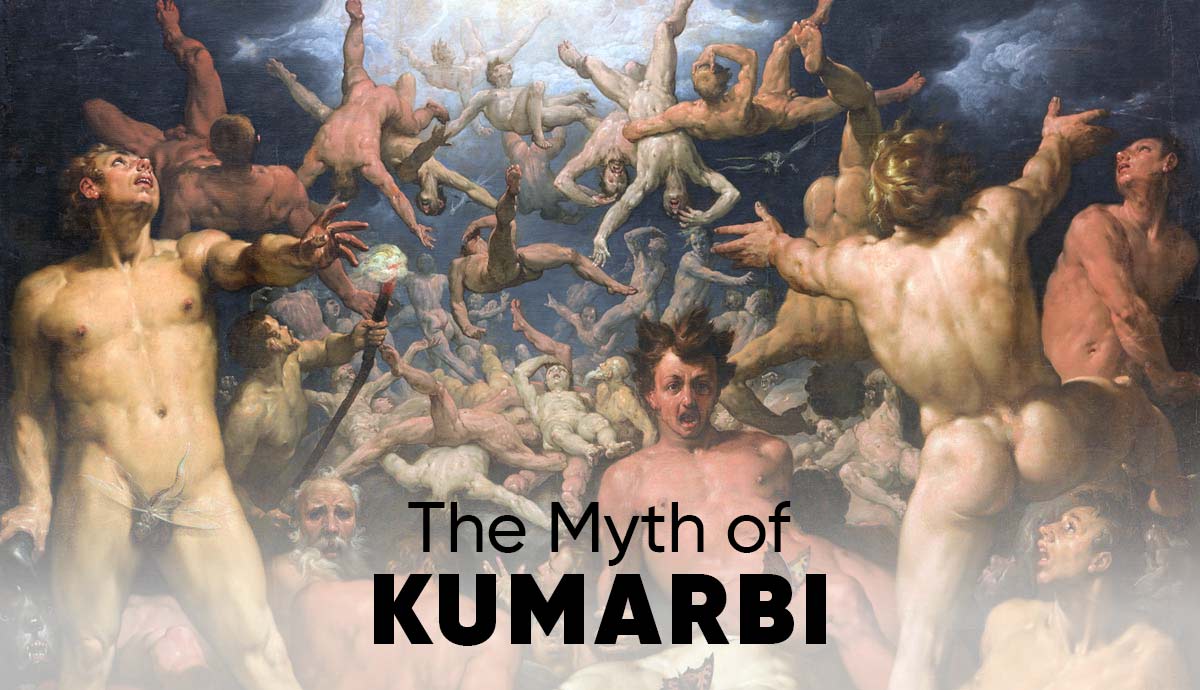

The religion of ancient Mesopotamia was complex and sometimes contradictory, as the role of each deity would change according to the needs of the time and the dominant cultures that worshipped these figures. However, the Mesopotamian gods fulfilled a number of roles that were essential to the people of the Fertile Crescent. To the Mesopotamians, these ancient deities gave birth to the universe and maintained both the physical and spiritual world around them. The Mesopotamian gods supported the social structure of the first civilizations and cared for the people in their day-to-day lives. When they died, as all mortals do, these deities cared for their souls in the afterlife.

Although worship of the Mesopotamian gods slowly died out following the fall of the Persian Empire, this religion heavily influenced the mythologies of later polytheistic civilizations, such as the Egyptians and Greeks. Concepts that originated in Mesopotamian mythology, such as the Great Flood or the conflict between chaos and order, also had an influence on monotheistic Semitic religions such as Judaism and Christianity. While gods such as Marduk and Enlil are no longer worshipped in large temples or carried through cities, these important deities undoubtedly had a lasting effect on all human history.