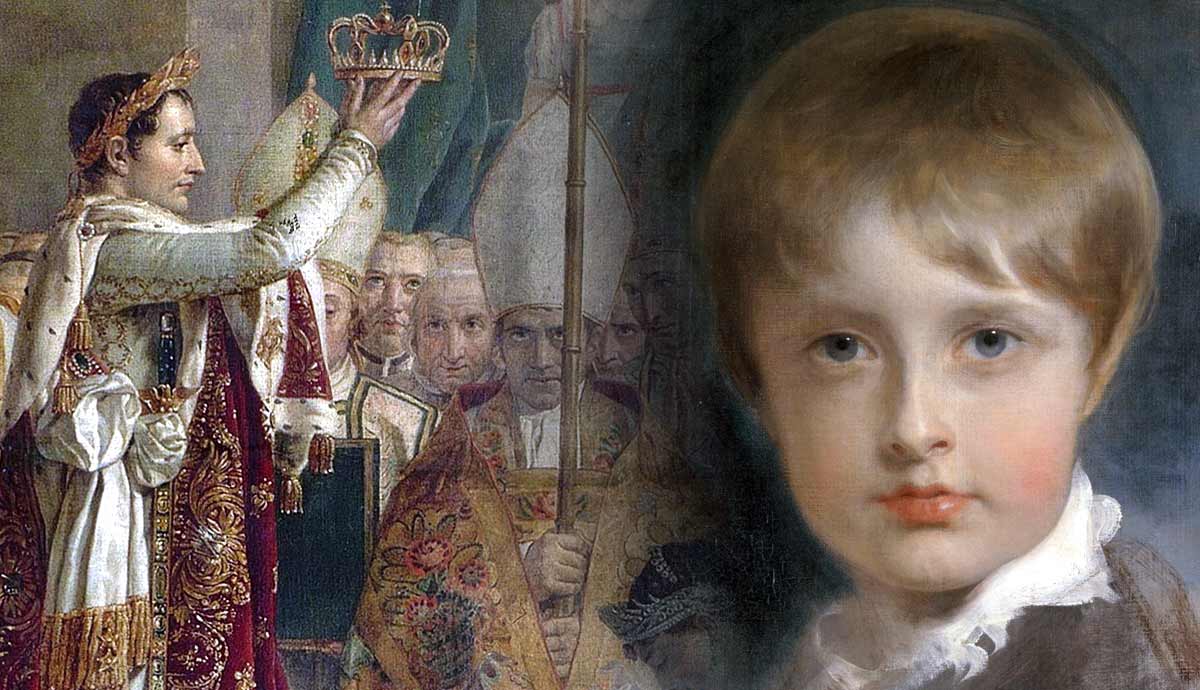

While in exile on the island of Saint Helena, Napoleon remarked to a loyal follower, “What a novel my life has been!” (Gueniffey, 1). Indeed, many aspects of Napoleon’s biography read like fiction. For example, by his mid-twenties, Napoleon was already a successful commanding general. By the time he crowned himself Emperor of the French in 1804, Napoleon ruled a country that extended its borders to include swaths of Italy, Switzerland, Germany, and the Low Countries (Leggiere, 1). Below, we’ll explore the details behind Napoleon’s remarkable life and career.

Where Was Napoleon Born?

Napoleon Bonaparte, France’s future ruler and conqueror of much of Europe, was born on the Mediterranean island of Corsica on August 15, 1769. The Republic of Genoa ruled the island before selling it to France in 1768.

France acquired the island amid a struggle for independence led by the charismatic Pasquale Paoli. Despite initial military setbacks, French troops forced Paoli into exile.

Napoleon’s parents, Carlo and Letizia, had eight children who survived infancy. Joseph was their oldest son, followed by Napoleon. Lucien, Elisa, Louis, Pauline, Caroline, and Jerome followed.

Historian Patrice Gueniffey explains that both of Napoleon’s parents had ancestral roots in present-day Italy. His ancestors arrived in Corsica during the 16th century (2014, 19).

While Napoleon’s parents supported Paoli, they decided to make peace with French officials. This decision paved the way for Napoleon’s future in France. Indeed, Frank McLynn points out that Napoleon began his military schooling in France in 1779. At the time, McLynn notes, Napoleon was a committed Corsican nationalist who idolized Paoli (2003, 18-19).

The young Napoleon would not break with his childhood hero’s Corsican patriotism until the early 1790s. By the end of 1793, Napoleon had participated in his first battle and became a hero in Revolutionary France for his role in the siege of Toulon. At the same time, Patrice Gueniffey notes that Napoleon’s family was no longer welcome in Corsica (2014, 120). Napoleon’s destiny would be shaped in France and not Corsica.

How Tall Was Napoleon?

Scholars have debated the question of Napoleon’s height as they have virtually every aspect of his life and career. According to historian Martyn Lyons, Napoleon “was a short man, even by the standards of the day” (1994, 1). Others suggest that our popular perception of Napoleon’s stature is the remnant of anti-Napoleonic propaganda.

You might be familiar with Napoleon’s nickname, the “Little Corporal.” Napoleon earned this affectionate nickname from his troops during his first successful campaign in Italy in 1796-1797. Historian David A. Bell notes that one French sergeant in 1796 considered Napoleon to be “small, skinny, very pale, with big black eyes and sunken cheeks” (2019, 29).

As Martyn Lyons points out, Napoleon’s enemies tended to call him “Boney” and the “Ogre” (1994, 1). So, was Napoleon the “Little Corporal” or a monstrous “Ogre?”

Napoleon’s height does not appear to correspond to the familiar satirical political cartoons of the age. According to most measurement methods of the era, Napoleon was not as short as often depicted in popular memory. The myth of his dramatically short stature originated from British propaganda. For example, British cartoonist James Gillray frequently depicted a diminutive Napoleon in his satirical political cartoons.

Nevertheless, Napoleon was not particularly tall, as we know from first-hand accounts. For example, Andrew Roberts notes that Arab historian Niqula al-Turk described Napoleon during the French invasion of Egypt in 1798 as “short, thin, and pale” (2014, 177).

Napoleon and Josephine

Napoleon married Marie Josèphe Rose Tascher de La Pagerie in March 1796. However, at the time of their marriage, she was known as the widow de Beauharnais. Moreover, Napoleon knew his wife by another name altogether: Josephine.

The woman Napoleon christened Josephine came from a family of prominent French settlers on the Caribbean islands of Martinique and Saint Lucia. Historians know little about her youth before her arrival in Paris at the age of seventeen in 1780.

Josephine was the mother of two children from her first marriage to General Alexandre Vicomte de Beauharnais. Historian Andrew Roberts notes that Josephine’s first marriage was an unhappy one. Beauharnais was abusive and even resorted to kidnapping their son during one of Josephine’s attempts to escape her husband (2014, 69).

Nevertheless, according to Roberts, Josephine tried to save her husband from the guillotine during the Terror in the French Revolution and was nearly guillotined herself (2014, 69).

By 1807, Napoleon cemented his control of the European continent by forging closer ties with Tsar Alexander I of Russia. At this point, Napoleon’s concerns turned to family and the absence of an heir. As Frank McLynn notes, debates raged in Napoleon’s inner circle about which royal house should be approached to arrange a marriage upon his divorce. Some, including Napoleon, sought a Russian princess. Others favored a match with a Habsburg princess. Ultimately, Napoleon divorced Josephine and married Marie-Louise of Austria (2003, 381-382).

Napoleon’s Letters to Josephine

Napoleon wrote a seemingly endless stream of passionate and often scandalously erotic letters to Josephine. Andrew Roberts explains that Napoleon wrote hundreds of pages to Josephine during his 1796 campaign in Italy. Despite the romantic nature of these letters, Roberts notes that Napoleon often signed them “Bonaparte” or simply “BP” just as he signed off orders to subordinate officers (2014, 82).

As a newlywed campaigning in Italy in 1796, Napoleon frequently wrote Josephine to join him in Milan. While she eventually left Paris to join Napoleon, Josephine had little desire to leave for Italy. Historian Martin Boycott-Brown notes that Josephine was having an affair with a young French officer. However, Boycott-Brown says Josephine gave Napoleon the excuse that she may have been pregnant and could not travel (2001, 321). Despite mutual infidelities over the years, Napoleon and Josephine formed a powerful team that helped Napoleon navigate his rise to power.

Napoleon’s letters and those of other leading French officials became a valued commodity for British propagandists. For instance, Andrew Roberts says British officials published captured French correspondence between 1798 and 1800. Most of these captured letters focused on French military reversals in Egypt. However, some were more personally damaging to Napoleon. For example, several letters from Napoleon to his brother Joseph detailed Josephine’s excessive spending and corruption (2014, 171-172).

Overall, Napoleon’s letters to Josephine reflected a key component of his personality: his boundless energy and ability to multi-task. For example, David Bell notes that in 1796-1797 alone, Napoleon wrote or dictated nearly two thousand letters (2019, 28).

Did Napoleon Have Children?

According to Andrew Roberts, had Napoleon’s empire been ruled by an established dynasty like the Habsburgs, it might have survived the succession of a brother or nephew to the throne. However, since the empire was only a few years old, Napoleon faced considerable personal and political pressure to father a legitimate heir to the throne (2014, 536).

Before marrying Austrian Princess Marie Louise in 1810, Napoleon had two illegitimate sons, Charles Léon Denuelle de la Plaigne and Alexandre-Florian-Joseph Colonna, Count Walewski. The French aristocrat Émilie Pellapra claimed to be Napoleon’s daughter. However, scholars suspect this claim to be false.

Napoleon believed he secured his dynasty’s future with the birth of his son, Napoleon François Charles Joseph Bonaparte, in March 1811. Napoleon’s heir is also remembered as Napoleon II, the King of Rome, and his Austrian title, the Duke of Reichstadt.

Napoleon was also the stepfather to Josephine’s children, Eugène and Hortense. Eugène became one of Napoleon’s most trusted lieutenants. For example, historian Alexander Mikaberidze explains that Eugène became the Viceroy of the Kingdom of Italy (2020, 285).

Napoleon arranged an unhappy marriage between Hortense and his brother, Louis. Ultimately, their son, Louis-Napoleon, would follow in his uncle’s footsteps and rule France as Emperor Napoleon III.

What Happened to Napoleon’s Son?

Napoleon II lived a tragically short and isolated life. As a child, he briefly served as the disputed successor to his father as Emperor of the French. However, he was destined never to rule or return to France. Instead, he became known as Franz, the Duke of Reichstadt, and lived in Vienna. He died of tuberculosis at the age of 21 in 1832.

His father, Napoleon I, died in exile on the remote island of Saint Helena in May 1821. According to Andrew Roberts, Napoleon last saw his young son and Marie Louise in late January 1814 (2014, 692).

References and Further Reading

Bell, D.A. (2019). Napoleon: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press.

Boycott-Brown, M. (2001). The Road to Rivoli: Napoleon’s First Campaign. Cassell & Co.

Gueniffey, P. (2015). Bonaparte: 1769–1802. (S. Rendall, Trans.). The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press (Original work published 2013).

Leggiere, M.V. (2007). The Fall of Napoleon: The Allied Invasion of France 1813-1814. Cambridge.

Lyons, M. (1994). Napoleon Bonaparte and the Legacy of the French Revolution. Macmillan Education.

McLynn, F. (2003). Napoleon: A Biography. Pimlico.

Mikaberidze, A. (2020). The Napoleonic Wars: A Global History. Oxford University Press.

Roberts, A. (2014). Napoleon the Great. Penguin.