Today, the Emperor Nero is known as one of Rome’s most decadent and tyrannical rulers. A princeling of just 16 when he was elevated, he proved so unpopular that he was dead by the age of 30, and Rome’s first ruling dynasty, the Julio-Claudians, died with him. But Nero was not born to be emperor. The son of a disgraced imperial princess exiled for treason, no one could have predicted that the preceding Emperor Claudius would choose Nero as his successor over his own biological son. So how was it that Nero became emperor of Rome?

A Tumultuous Childhood

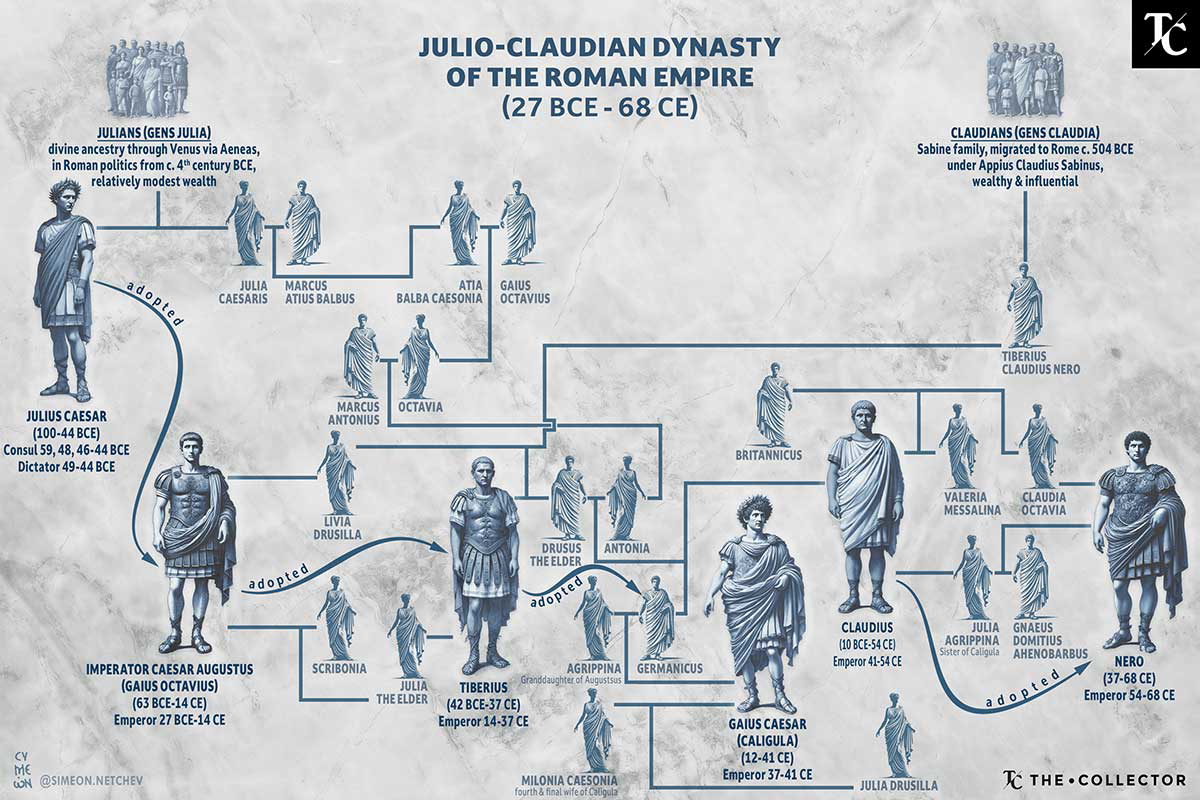

Nero was born in 37 CE as Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus. He was the son of Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus, a son of the first Roman Emperor Augustus’ niece Antonia Minor, and Agrippina the Younger, a great-granddaughter of Augustus, daughter of the popular general Germanicus, and sister of the then reigning Emperor Caligula. This made Nero a very blue-blooded member of the reigning Julio-Claudian clan, and the infant was Caligula’s closest male relative when he died in 41 CE.

However, Caligula was very fond of his sister Drusilla and even named her husband Marcus Aemilius Lepidus as his heir. But when she died in June 38 CE, Caligula became suspicious of all those around him. Caligula accused his other sisters, Agrippina and Livilla, of conspiring with Lepidus to overthrow their brother. Agrippina was sent into exile, and her son was sent to live with his paternal aunt Domitia Lepida, and his inheritance was taken away from him.

When Caligula died, the young Nero’s age and diminished position meant that none would have considered him for power. But the Praetorian Guard chose an even less expected heir, Claudius, the uncle of Caligula, who had previously been kept out of the spotlight for health reasons.

Marriage Machinations

Upon his rise to power, Claudius arranged for the recall of his exiled nieces, Agrippina and Livilla, and Agrippina was reunited with her young son Nero, and their inheritances were reinstated. Their fortunes rose as Agrippina married the wealthy and influential two-time consul Gaius Sallustius Crispus Passienus, who divorced Nero’s aunt Domitia Lepida to make the match. He died and left his estate to Nero.

Agrippina made an even more favorable marriage on January 1, 49 CE, when she married her uncle, the Emperor Claudius, despite taboos around the close relationship. Some historians believe that part of the motivation for the marriage was to bring Nero into the direct imperial line as a potential heir, alongside Claudius’ biological son with his previous wife, Messalina. Britannicus was four years younger than Nero, and perhaps his youth and Claudius’s age and health made the question of an older successor feel pressing.

Becoming Heir

Agrippina certainly took advantage of the situation to promote her son’s fortunes. She was no doubt influential in having Claudius adopt her son in 50 CE, when he officially became known as Nero, and was granted the title of princeps iuventutis (leader of the youth), which Augustus had used to mark out his young heirs 50 years earlier. Agrippina probably also encouraged him to be awarded the toga virilis, or symbol of manhood, in 51 CE at the age of 14, before the normal age. She was instrumental in arranging the marriage of Nero and Claudius’s daughter, Octavia, in 53 CE, and having him elected consul designate for the year 56 CE, when he would be 20.

Agrippina employed one of the best minds in the Roman Empire, Seneca, a famous philosopher, to tutor her son and teach Nero how to rule, and also secured the loyalty of the Praetorian Guard, instrumental in the imperial succession, through her favorite, the praetorian prefect Sextus Afranius Burrus. When Emperor Claudius died in 54 (allegedly after eating poisoned mushrooms given by Agrippina), Nero was proclaimed emperor by the Praetorian Guard and with the Senate’s approval. The 16-year-old was now master of the Roman Empire.

Princeps and Regent

While Nero was made emperor, during the early stages of his reign, the youth was overshadowed and influenced by his ambitious mother. The extent of Agrippina’s influence can be best seen in depictions of the imperial family, especially on the coinage minted in the first years of Nero’s reign. One of the earliest coins features Agrippina on the obverse — the place traditionally reserved for the emperor. Other coins show a joint portrait of mother and son, suggesting an equal relationship. The most striking example of Agrippina’s power is the relief from Aphrodisias (in modern-day Western Turkey), where Agrippina is portrayed as the source of the emperor’s authority, crowning her son.

However, the relationship between mother and son soured quickly. Agrippina’s increased meddling in imperial politics and her son’s private life was unacceptable to Nero and his other advisors, who wanted to exert greater power over the princeps. Reportedly fearing that Agrippina might use Britannicus against him, Nero poisoned his stepbrother in 55 CE.

The already bad relationship between mother and son turned worse when Nero started an affair with an ex-slave girl, Claudia Acte. Thus, when Agrippina tried to befriend Nero’s wife, Octavia, Nero exiled his mother from the Palace in 56 CE. However, Agrippina’s influence continued to manifest through her allies at the court, such as Seneca or Burrus. Nero had to get rid of his mother if he wanted to establish himself as a sole ruler.

Taking Sole Power

Eventually, Nero decided on a final solution to remove his troublesome mother. Some sources suggest that this was partially influenced by his relationship with Poppaea Sabina, even though he was still married to Octavia. Other sources suggest that Nero was motivated by a plot to replace him with his cousin Gaius Rubellius Plautus, in which Agrippina may have been implicated.

The sources on Agrippina’s death differ and contradict each other, but they all agree that Agrippina survived several assassination attempts. The most infamous one involved a self-sinking pleasure barge from which Agrippina miraculously escaped, able to swim ashore. However, Agrippina’s luck finally ran out in 59 CE when Nero reportedly sent assassins to her villa.

After the death of his mother, Nero became the sole emperor, finally divorcing Octavia and marrying Poppaea in 62 CE, only to be kicked to death by her husband in 65 CE.

Agrippina’s death is generally seen as a turning point in Nero’s reign. With no significant checks on his power, he sank into megalomania and began to indulge in unsavoury activities. It is difficult to know how much of this criticism is legitimate and how much was the result of Nero being posthumously vilified as the last member of one dynasty, sacrificed to justify the rise of the next.