Since the 2019 fire, people across the spectrum of religious practices as well as influential faith organizations, have come to the forefront to talk about the need to conserve Notre-Dame de Paris. How many know that the site that holds the legendary crown of thorns the Bible claims was placed on the head of Christianity’s dying savior and was also a holy place for pagans of old? There is something about Notre-Dame, something perhaps in the French land that lies beneath it, that has drawn people to worship there since before the advent of Christianity.

Druids and the Early Spiritual Landscape

Before the Roman invasion, France was known as Gaul and primarily populated by families of subsistence farmers. There were some quasi-urban centers where the population gathered, as people had long sensed that there is strength in numbers. These places were led, both administratively and spiritually, by druids. And, in places like the site of Notre-Dame Cathedral, druids led the people to worship the deities that would make fields fallow and rains plentiful for life-sustaining seedlings. These Gaulish priests and their followers participated in rituals that frequently focused on natural elements like springs and groves.

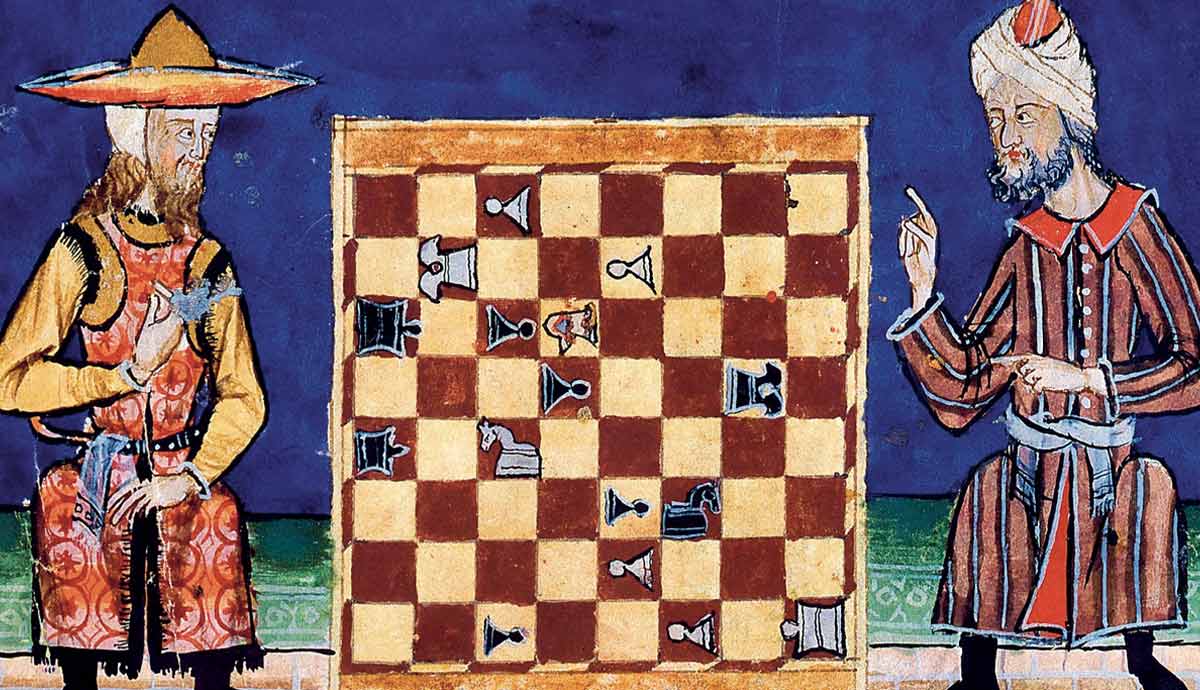

Then, the Romans invaded, despite the violent pushback of the less militarily organized Gaulish people. The conquerors named the city they built here Lutetia, referencing the swampy quality of the land. These Roman forces not only established cities with temples for the gods they brought with them from home but also introduced a number of deities who meshed into an amalgamation of Roman/Gaulish figures unique to the area. A famous column from Lutetia, now Paris, shows both Roman and Celtic gods, illustrating the blend of religious practices during this era.

From Pagan Worship to Roman Temples: The Early History of Notre-Dame

As the Roman Empire expanded, so did its influence on the spiritual and cultural landscape of the conquered people it meant to integrate. Beneath what is now Notre-Dame, the foundations of a Roman temple to Jupiter still bolster the more modern structure. It is believed that this temple of the Roman patriarchal deity was the center of religious life in Lutetia.

However, the Roman provinces were also where Christianity began to spread. The descendants of people who followed the ways of the land-loving druids and perhaps visited columned Roman temples were now converting to Christianity. In those early years, Christians who came to proselytize in Gaul were often martyred. Their deaths led to eventual sainthood. With the conversion of the entire empire under the reformed Constantine, many temples were refashioned into churches.

As this happened Lutetia morphed more and more into urban Paris. The local martyr, St. Denis, played a significant if somewhat mythical role in this transformation. According to the Parisian locals, after being beheaded on Montmartre, St. Denis carried his severed head for a miraculous stretch before collapsing at the site that would later become a basilica in his honor. This story, still repeated to this day, underscores the burgeoning Christian presence and the blending of Roman and early Christian spiritual practices.

First a Woman, Then Another

One example of the magnificent blend of the early modern era and prehistory is the veneration of both St. Brigid and the Black Madonnas. They both serve as examples of the intersection between pagan and Christian traditions. Originally a pagan fire goddess, Brigid was associated with healing, poetry, and smithcraft. As Christianity spread, she, much like the gradual morphing of Notre-Dame’s site itself, transformed into a Christian icon. The once solidly pagan figure of female strength then became a powerful symbol of the blending of pagan and Christian beliefs by converts unwilling to forsake all of their closely held mythos. Saint Brigid’s Day, celebrated on February 1st, marks this transition and continues to be a significant cultural event, particularly in Ireland and France, specifically in Paris.

The veneration of Black Madonnas further illustrates the persistence of pagan rituals within Christian contexts. These statues, often found in places once sacred to ancient goddess worship, represent a blend of pre-Christian and Christian beliefs.

One such Dark Madonna, also known as Our Lady of Good Deliverance, has been celebrated for centuries and is believed to offer protection and resilience to those who call out to her, particularly to those standing up to abusers. It is thought that she once adorned The Basilica and Cathedral of Saint-Étienne, the church that predated the building of Notre-Dame de Paris by approximately six centuries.

This early basilica and home to Our Lady of Good Deliverance was torn down around the mid-1100s when construction began on the cathedral’s foundations. The original was lost, but a replica of Our Lady was created in the 14th century and can still be visited today at a fellow Parisian church, the Congregation of the Sisters of St. Thomas of Villeneuve. Our Lady came to be in this place after being taken from her pedestal and hidden away in a private home during La Terreur.

The symbolism of the fiery goddess as a protectress is deeply rooted in these traditions. Saint Brigid, for example, was revered for her ability to provide solace and empowerment. Similarly, praying to the Black Madonna was believed to help people confront and overcome their challenges. This protective aspect of pagan goddesses carried over into Christian veneration—despite a lack of females depicted in positions of authority—demonstrating how these ancient beliefs were adapted and preserved within a new religious framework.

In England and France, the continued veneration of Black Madonnas and the incorporation of pagan elements into church services and religious festivals highlight the enduring influence of these ancient traditions. As in the case of Our Lady of Good Deliverance, to whom many prisoners of the revolutionary mobs prayed, beliefs may shift but often find a new home with the faithful.

Overall, the transition from paganism to Christianity in Western Europe was not a simple replacement of one set of beliefs with another. This would have been too sudden and nearly impossible to enforce. Instead, it was a complex process of adaptation and integration, where ancient practices and symbols were reinterpreted by both those in power and the believers themselves. The enduring presence of figures like Saint Brigid and the Black Madonnas in religious life today serves as a reminder of the deep and lasting connections between these two spiritual traditions. So many participating may not even know that they’re one in a line stretching back to prehistory, of people praying to a woman for just outcomes and safeguarding.

Eugène Viollet-Le-Duc: The Architect Who Reshaped Notre-Dame de Paris

This wasn’t to be the last of France’s transitions of belief. The cathedral itself had a before and after a period that was distinctly separated by the ravages of the Reign of Terror. Prior to this event, the cathedral library boasted between 10,000 and 12,000 volumes, evidence of its importance and the dedication of those who contributed to its growth. Although approximately 300 manuscripts were sold to the king by the mid-18th century, the library’s remaining volumes included illuminated missals made for notable bishops like Pierre d’Orgemont and Gérard de Montaigu, several liturgical manuscripts from earlier eras, the only known copy of the first edition of the Shepherds’ Calendar, and works by Charles Perrault.

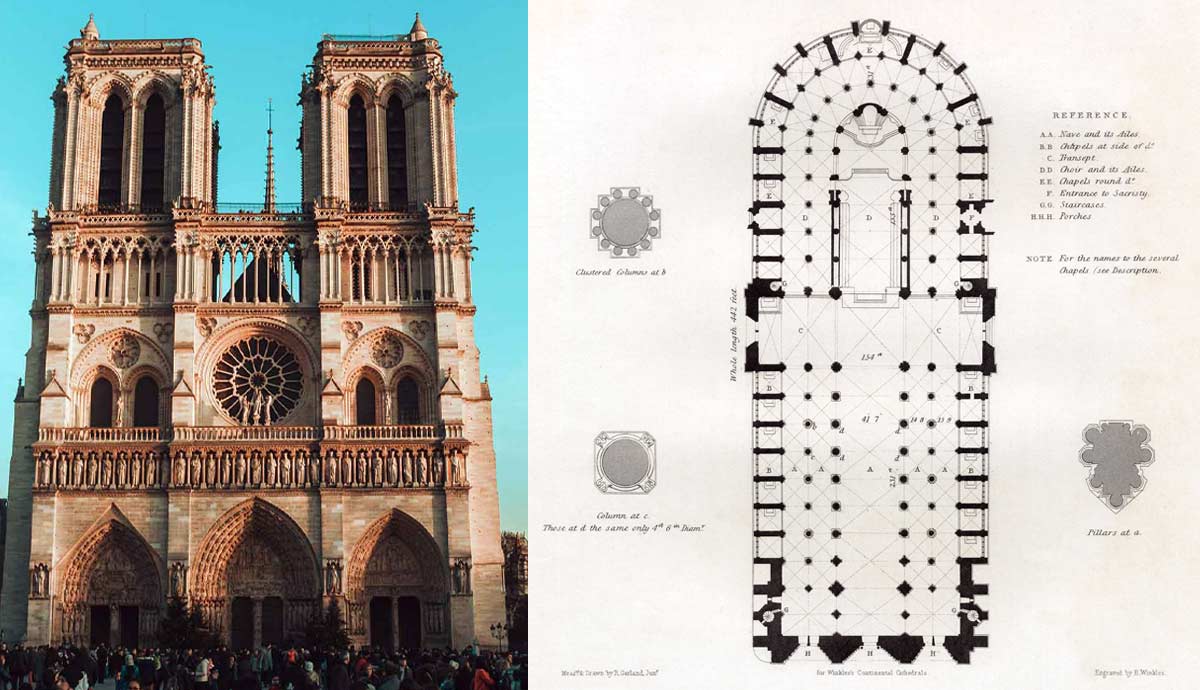

The French Revolution didn’t just spell an end to the monarchy. By the mid-19th century, Notre-Dame de Paris was left in a state of disrepair entirely intentionally. The ravages of social upheaval had left scars: statues of the kings of Israel had been beheaded much like St. Denis. The cathedral’s bells that once called people to service had been melted into cannons. Acid rain had eroded the artistry of the stonework. Gargoyles and other imposing statuary that once adorned the church had diminished to rather sorry blobs of masonry.

Eugène Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc, a young man in his 30s, was chosen in 1844 to manage the restoration project. Eugène believed he could not only restore the cathedral but improve upon it. His vision and dedication breathed new life into the crumbling structure. He achieved this despite peers calling him bourgeois and arrogant. Viollet-le-Duc did restore Notre-Dame’s Gothic grandeur but allowed his dreams of modernization to inform some of the details. He accomplished his goal of being both innovative and committed to historical accuracy.

Notre-Dame: A Symbol of Resilience and Faith

As of today, Notre-Dame stands as a symbol of resilience. Until the fire in the cathedral’s roof, it was the home of one of Christianity’s most revered relics—the crown of thorns said to have been worn by Jesus during the Crucifixion. This priceless relic was saved from the flames and now awaits Notre-Dame’s restoration in the Louvre. This cathedral, with its gothic arches and smoke-stained but majestic presence, has witnessed centuries of change, turmoil, and renewal.

The 2019 fire that ravaged the ancient site caused an outpouring of support. Calls for its restoration came from all corners of the globe, highlighting the reverence for this iconic spiritual home of both people alive today and those who came long before. Notre-Dame, a sanctuary for druids, Romans, and Parisians alike continues on as a testament to human history and cultural heritage.

And, best and perhaps most macabre of all, many of those who came before us are still there. After the devastating fire, preventive archaeology led to the discovery of two lead sarcophagi buried where the cathedral’s transept intersects its nave. One set of remains was determined to be a high-ranking priest. The other is believed to belong to a knight from the 15th century, nicknamed “Le Cavalier” by researchers since his bones show he probably lived much of his life astride a horse.

The sarcophagi were carefully opened and analyzed at the Toulouse University Hospital, revealing fascinating details about their occupants. The knight’s skull, elongated due to a headband worn since infancy, was buried in a flower crown. The presence of embalming plants indicated a high-status individual but one who suffered from a chronic illness and oral disease. These findings provide a glimpse into the lives and deaths of the individuals who were part of Notre-Dame’s long and storied history.