By the time of her death in 11 BCE, Octavia the Younger had lived through some of the most tumultuous decades in Roman history. As the Roman Republic entered its death throes, Octavia was caught between rivals, as her brother, Octavian, vied with her husband, Mark Antony, for control of the Empire. Although she did not live to see the Julio-Claudian dynasty emerge in its full complexity and power, Octavia’s legacy would shape the first era of the Principate, as her grandsons and great-grandsons would go on to become emperors.

Octavia’s Family: History of the Gens Octavia

Octavia the Younger was a member of the gens Octavia. This was a plebeian family that originally hailed from the town of Velitrae, in the Alban Hills south of Rome. Although the family would go on to be one of the most significant in Roman history, their origins appear modest in comparison. The gens first came to prominence around 230 BCE, when Gnaeus Octavius Rufus became a quaestor, a lower magistracy responsible for financial administration.

Later, the Octavii family would attempt to craft a suitably antiquated history for themselves; distinguished family trees and genealogies were valuable in the febrile atmosphere of competitiveness in the late Republic. Suetonius records the story that the Octavii owed their citizenship to Lucius Tarquinius Priscus. Whether the fifth king of Rome was responsible for enfranchising the family is hard to determine. Certainly, it is not recorded in other sources for the early Republic, such as Livy.

Indeed, Octavian, later to be known as Augustus, would record that his biological father, Gaius Octavius, was a novus homo or “new man.” This term refers to those men in ancient Rome who became the first of their family to serve in the Senate. Cicero remains the most well-known of these in the history of the Republic.

Gaius’ emergence into Roman politics would have significant ramifications. After his first marriage ended with the death of his wife, Ancharia, Gaius married Atia, who was the niece of Julius Caesar. The details of how they met are not well known, but it may be a coincidence of geography. Atia’s paternal family hailed from near Velitrae. Atia and Gaius had two children: Octavius, born around 63 BCE, and Octavia the Younger, born around 69 BCE. When their great-uncle Julius Caesar was murdered in 44 BCE, it was revealed that he had adopted Octavian as his heir. The children of the gens Octavia were thrust into the center of Roman politics as civil war loomed.

Octavia’s First Marriage: Gaius Claudius Marcellus

Although she would become one of the most significant women in Roman history, because of the patriarchal nature of that society, Octavia’s prominence was inherently linked to her relationships with men. Her marriages would prove important to the later course of imperial history.

Some time before 54 BCE, Octavia was married to Gaius Claudius Marcellus. He belonged to the gens Claudia, one of Rome’s most prominent patrician families. The family included many illustrious members. Appius Claudius Caecus was the man responsible for the Via Appia, the oldest road in Rome. Appius Claudius Pulcher had been consul in 212 BCE during the Second Punic War. Marcus Claudius Marcellus famously received the spolia opima, one of Rome’s highest military honors, when he defeated the Gallic king Viridomarus in single combat in 222 BCE.

The marriage between Octavia and Gaius Marcellus was fruitful, despite Octavia being significantly younger than her husband. Octavia bore Gaius three children. There was one son, Marcus, and two daughters, Claudia Marcella Major and Claudia Marcella Minor.

Political Pawn: Octavia, Pompey, and Mark Antony

A timely reminder of Octavia’s lack of personal agency in the Roman world would come not long after her marriage to Gaius Marcellus. The men in her life already recognized that the young bride was a potentially useful bargaining chip in the high-stakes politics of the late Republic. Her great-uncle, Julius Caesar, wanted to wed the young Octavia to his political ally, Pompey. The reasoning behind this was that Pompey’s wife, Julia, Caesar’s daughter and Octavia’s cousin, had died. Another marriage between the two families would consolidate their political alliance.

Unfortunately for all involved, and the Republic itself, Pompey declined the proposal. Instead, he married Cornelia Metella. Not only did this indicate that the relationship between Pompey and Caesar was deteriorating, but it left Octavia married to Gaius Marcellus for the time being. Marcellus himself was opposed to Caesar’s growing power. In fact, during his consulship in 50 BCE, Gaius (unsuccessfully) attempted to have Caesar recalled from his 10-year governorship in Gaul.

Perhaps because of his relationship to Octavia, and also likely as a result of his not fighting against Caesar’s forces at the Battle of Pharsalus in 48 BCE, Gaius Marcellus’ anti-Caesarian views did not cost him his life. When he died in 40 BCE, however, Octavia was not left to grieve the passing of her first husband for long. By senatorial decree, she was married to Mark Antony, Caesar’s second-in-command, later that very same year. She was to be Antony’s fourth wife, after the death of Fulvia.

By this time, Caesar had been assassinated, but Octavia still found herself a political pawn for the men in her life. It was hoped that her betrothal to Antony would bolster the uneasy alliance between the two men vying to replace Caesar as the leading man in the Republic: Antony and Octavian.

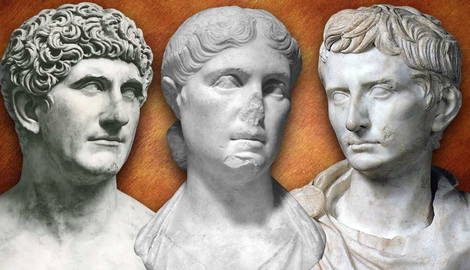

For all appearances, it seems that Octavia was a loyal wife to Antony in the early years of their marriage. Certainly, they had two children together: two daughters, Antonia Major and Antonia Minor. Octavia raised these alongside her own children and step-children, partially in Athens, where she had travelled with her husband, as recorded by Plutarch. A striking indication of Octavia’s importance during this period was demonstrated by her appearance on coinage minted by her husband. She was one of the earliest Roman women to appear in this medium.

The Matrona and the Pharaoh: Octavia and Cleopatra

Despite the importance of Octavia to Antony suggested by her numismatic portrayals, she was not able to compete with Cleopatra, a Queen and a Pharaoh, for her husband’s attention and affections. The two first met in Tarsus, Asia Minor, in 41 BCE. Antony had summoned the Queen of Egypt to him, and there she hosted the Roman triumvir aboard her ship. At the meeting, Cleopatra was able to confirm her loyalty to Rome.

The encounter also gave her the opportunity to invite Antony to Egypt. So began one of history’s most famous and romanticized affairs. Well received in Alexandria upon his visit, Antony decided to effectively abandon his wife. While Octavia returned to Rome, her husband continued to cavort with Cleopatra in Egypt. It was to prove disastrous for Antony. His elopement with the foreign queen allowed Octavian’s propaganda to go into overdrive.

The image circulated of Antony by his enemies was of a man who would abandon Rome for the riches and licentiousness of the east as soon as he was victorious. In creating this impression, Octavia’s return to Rome to continue to raise her children would have been extremely valuable as a point of contrast.

The contrast was sharpened by Octavia’s ongoing commitment to Antony for a time. For instance, during her second husband’s abortive campaign against Parthia, it was Octavia who had attempted to secure the fresh troops and funding Antony needed in 35 BCE. By this point, however, the union between the two was well and truly fractured. Arriving in Athens with the resources she believed her husband needed, Octavia was greeted with a letter. On her husband’s orders, she was to go no further. They were divorced in 33 BCE, and Antony gave orders that Octavia be ejected from his house in Rome.

Despite the breakdown of her marriage and the embarrassment she may have felt from being abandoned in favor of the Egyptian Queen, Octavia continued to dutifully raise her children. This included those born of her marriage to Antony. Because of her resolute commitment to her marriage and children, Octavia came to be viewed as an embodiment of traditional Roman feminine virtues. In contrast to Antony, seduced by the riches of the “other,” Octavia was recognized as an idealized Roman matrona.

Imperial Heir Apparent? Octavia and Marcellus

The end of Octavia’s marriage in 33 BCE confirmed what was by now an open secret. The relationship between Antony and Octavian had utterly broken down, and the fate of the Roman world would once again be decided by war. In the end, it was the young man, Caesar’s adopted heir and the brother of Octavia, who would triumph. The decisive victory came at the Battle of Actium in 31 BCE. With Octavian’s victory came the death of the Republic, although the new master of the Roman world appears to have done his very best to disguise the extent and character of his autocratic powers.

Soon to be known as Augustus, one of the defining problems of the long reign of Rome’s first emperor was the question of succession. Since Augustus did not have any sons of his own, who should be the one to follow in his footsteps as princeps?

One possible successor was Marcus Claudius Marcellus, the eldest son of Octavia and her first husband, Gaius Marcellus. As Augustus’ nephew, he was the emperor’s closest male relative. Although he was never formally adopted by Augustus, his stellar early political career suggests that Marcellus was favored by the emperor. Along with his cousin Tiberius, Augustus’s stepson from his wife Livia, Marcellus served under his uncle in the Cantabrian Wars in Hispania. In 25 BCE, he was married to Augustus’ daughter, Julia.

Any further plans for Marcellus on Augustus’ part were cut tragically short. Both uncle and nephew contracted an illness in Rome in 23 BCE. While Augustus himself recovered, it proved fatal to Marcellus, and the young man died at Baiae, in Campania. A sign of his status within the nascent imperial dynasty came with the internment of his remains in the Mausoleum of Augustus, the monumental tomb the emperor had constructed for himself on the Campus Martius.

The loss of her son devastated Octavia. It was claimed that the lines of Virgil’s Aeneid, which recount Aeneas meeting with Marcellus in the underworld, so moved Octavia that she fainted. Upon recovering her composure, she is alleged to have rewarded the poet handsomely for his work.

Monumental: Octavia’s Legacy

Octavia died of natural causes in 11 BCE. After her death, Octavia was interred within the Mausoleum of Augustus, where she was once more reunited with her son. According to Seneca, she was so devastated by the death of Marcellus that she effectively retired from public life. This seems unlikely, however, given her extraordinary prominence in the Augustan City of Rome.

Octavia was one of several women in the new Julio-Claudian dynasty who were publicly visible in the new regime, which testified to the important ideological role of women in the Principate. Through their children, they were the guarantors of future stability. Alongside this, their feminine virtues, closely linked to their maternal roles, were celebrated. Octavia, along with Livia, became some of the earliest women in Rome to have their likenesses displayed to the public on a large scale, for example, on coinage and in artworks. This latter was an honor that had previously been limited to only one woman, Cornelia, the mother of the Gracchi.

Elsewhere in Augustan Rome, the city of marble emerging from one of brick, there were striking signs of Octavia’s importance in the city’s architectural fabric. The most notable of these, which still survives in part to this day, is the Porticus Octaviae in the south of the Campus Martius. Originally built on the orders of Quintus Caecilius Metellus Macedonicus in 146 BCE with the spoils of the Achaean War, the porticus enclosed the temples of Juno Regina and Jupiter Stator to the north and south. Within the porticus, there were also the equestrian statues of Alexander the Great’s generals, looted from the Greeks. The porticus was restored by Augustus in 27 BCE and renamed in honor of his sister; it was now known as the Porticus Octaviae. Within the walls of the porticus, there was also a library, which Octavia herself had ordered built in memory of her beloved son Marcellus. The compound included an assembly hall, the curia Octaviae, and lecture rooms. Remains of the Porticus, heavily restored by Septimius Severus after it was damaged in a fire, are still visible today.

Octavia would also leave her legacy through her bloodline, as a direct ancestor of three of the following Julio-Claudian emperors. While she was not a blood relative of Augustus’s stepson and heir, Tiberius, through her daughter with Mark Antony, Antonia, she was the great-grandmother of the emperor Caligula and the grandmother of his uncle and successor, Claudius. Octavia was also the great-grandmother of Caligula’s sister, Agrippina, who would go on to marry her uncle, Claudius, and become powerful in her own right. She was also the mother of the final Julio-Claudian emperor, Nero.