A Scotsman in Greece. This is where the story of the Parthenon Marbles controversy begins. When Lord Elgin arrived in Athens at the beginning of the 19th century, the Parthenon was in ruins and Greece was under foreign occupation. A few years later, when Elgin left Greece, the Parthenon had been stripped of many of its metopes, figures, as well as much of its friezes. The controversy surrounding the Elgin Marbles, as they came to be known, had just begun. It continues today, more than two centuries later, with the fate of the Marbles remaining at the heart of the repatriation debate.

The Parthenon Marbles: Stolen Artworks, Global Heritage?

The debate surrounding restitution (or repatriation) sits at the center of a series of “interlinked questions about past, present, and future rights and wrongs” (Lundén). Those in favor of repatriation believe that cultural artifacts that were looted or purchased during armed conflict or in a colonial environment should be returned to the countries (and descendants) of the people who created them.

Just as colonial endeavors sought to exercise control over the colonized country, its people, economy, and self-determination, repatriation enables former colonies to reclaim their cultural past. It allows them to finally take control of the narrative surrounding their history, and to reaffirm their international presence, and cultural and economic independence from former colonizing powers and outside notions of Western superiority.

As Kiwara Wilson writes, repatriation allows former victims to control “their past through controlling the objects of their cultural past,” because “he who controls the objects controls the story.” In this sense, works of art that were stolen, bought, or acquired under unclear circumstances merge with the very notion of the nation’s past. These works effectively become the nation’s past—emblems of the nation’s identity; fetishes of the nation’s past and the violence that stained it; symbols of a specific culture’s ability to create lasting works of art, and an opportunity for former colonies to shake off the legacy of colonialism and its cultural burden.

Those in favor of repatriation tend to believe that returning stolen artworks is the first step in pushing former colonizing powers to both acknowledge their colonial past and take active responsibility for the economic (and, of course, cultural) damage inflicted on the colonized.

On the other hand, those who oppose and resist repatriation efforts maintain that art does not belong to a single nation or people, that the Benin Bronzes and the Parthenon Marbles are part of a shared global heritage, a heritage that is, first and foremost a testament to humankind’s ability to create timeless artworks. Their location becomes irrelevant. The fact that they can now be appreciated in museums far from the place where they were conceived—museums visited by thousands of people every year and which claim to be “universal” and “encyclopaedic”—is a testament to the ever-evolving history of dialogue between nations and a means of promoting cross-cultural understanding.

Critics of repatriation efforts also raise questions about the ethics of restitution. For example, should fragile works be returned to countries with unstable political situations, countries that have recently emerged from prolonged periods of warfare and cannot guarantee the proper conservation of these artworks? If it were proven that the artworks were safer and more accessible in Western museums, would it then be right to refuse any claims for their return?

This, in turn, begs another question: more accessible to whom? To the descendants of those who created them or to Western society? And what about artworks that were “legally acquired” under laws that, despite existing in contexts of subjugation, were valid?

From Athens to London

The Parthenon Marbles will forever be associated with the name of Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin (1766-1841), the Scottish-born British ambassador to the Ottoman Empire; Lord Elgin, as he’s commonly known. By the time he set foot on the Acropolis, the Parthenon, the temple dedicated to the goddess Athena, was already in ruins. Much of its roof and interior had been destroyed, and a Venetian mortar round fired from the Hill of Philopappos on September 26, 1687, during the Morean War, brought down three-fifths of the sculptures.

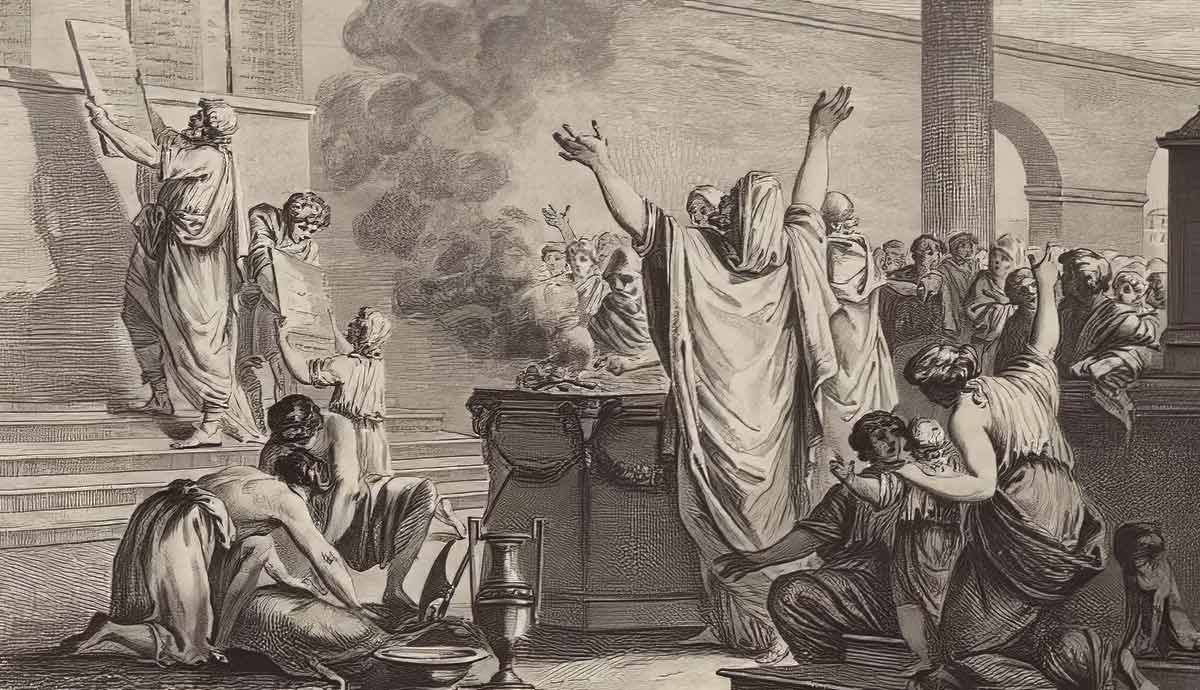

At this time, the Parthenon was being used as an ammunition store. Before that, it had served as a Christian church, known as either the Church of the Parthenos Maria or the Church of the Theotokos (Mother of God). Its orientation had been changed, icons had been painted onto its old walls, and ancient sculptures had been removed and lost.

More than four centuries after it became the fourth most important Christian pilgrimage destination, the Parthenon was converted into a mosque. Christian altars and icons of Christian saints were either removed or covered up. A minbar—the pulpit from which the imam delivers his sermon—was installed.

A few decades before Greece finally achieved independence in 1832, Lord Elgin was granted permission by the Ottoman authorities to take measurements and remove statues from the ruins of the Parthenon. Which is what he did. Statues and figures were removed not only from the Parthenon but also from the various buildings that make up the Acropolis. Some came from the Temple of Athena Nike, on the southwestern edge of the Acropolis; others were removed from the Erechtheion, on the north side, and others still came from the Propylaia, the monumental Greek Doric complex that served as the gateway to the Acropolis.

In 1816, the British Museum purchased the marbles from Elgin following a vote by the House of Commons. By this time, Elgin was a 50-year-old bankrupt former politician. An inquiry found that he had acquired the marbles legally, thus legitimizing the British Museum’s acquisition. However, in 2024, Zeynep Boz, the Turkish culture ministry’s anti-smuggling official, publicly questioned and rejected the legality of Elgin’s actions. There was no actual evidence, no official document or firman (a royal mandate or decree) from the Sublime Porte containing the sultan’s seal or signature to prove that the Scotsman had been granted permission by the Ottoman authorities.

Although an Italian translation of the firman does exist and is now held by the British Museum, historians have been unable to find the official copy in the archives from the imperial area.

The British Museum… or the Brutish Museum?

Over 200 years after the British Museum acquired them, the Parthenon Marbles have become widely known as the Elgin Marbles—a name that marks the most recent turning point in the history of the Parthenon and the Acropolis itself, the moment when some of the most important and iconic pieces of Greek art and history became intertwined with British society.

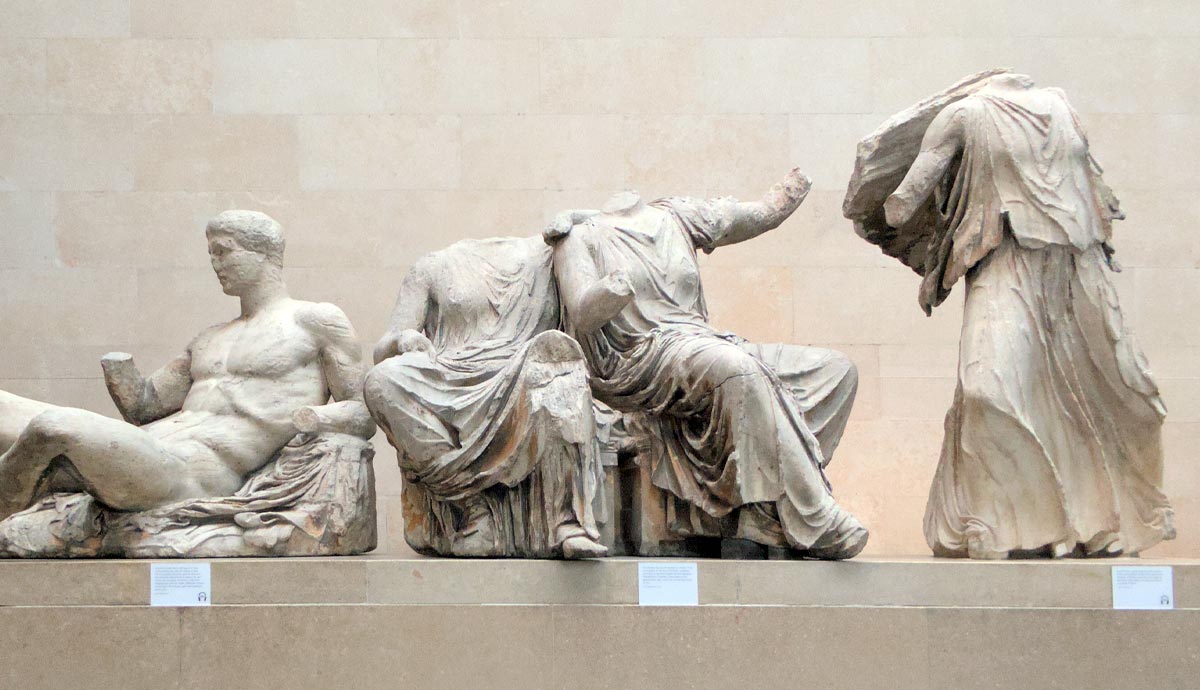

The British Museum currently holds 75 meters (247 feet) of the original Parthenon Frieze, which was sculpted between 443 and 438 BCE, and depicts the procession held during the Great Panathenaia, the festival commemorating the birthday of Athena. While 50 meters (164 feet) of the frieze are displayed in the Acropolis Museum in Athens, close to where they were conceived and created, most of the rest are housed in the British Museum and remain at the center of the restitution debate. The British Museum also houses 17 pedimental figures and 15 high-relief metopes.

These decorated panels depict the battle between the Lapiths and the Centaurs at the marriage of Peirithoos and once adorned the exterior of the Parthenon, just above the exterior colonnade. Long after Elgin returned home with the Parthenon metopes, sculptures, and pieces of frieze, Greece formally sought the return of the Parthenon Marbles. The year was 1893. Four years later, in 1987, the entire Acropolis was inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage site.

Among pro-repatriation activists, the anniversary of the artifacts’ acquisition by the British Museum is known as the “black anniversary.” Those who have publicly campaigned for the marbles to be returned to Greece include British historian and professor Paul Cartledge, who once asked: “‘Where best for the Parthenon Marbles?’ It’s a no-brainer. In the newish Acropolis Museum. The clue is in the name.”

“There is no other example of a piece of art as crudely dismembered as the Parthenon, with even the heads and bodies of individual sculptures located in different countries,” writes Constantine Sandis. He then marvels at the fact that “if the missing sculptures and fragments of this aesthetic travesty were to be reunited with those in the New Acropolis Museum, visitors could study them as one entire whole, with a direct view of the monument to which they belong.”

The British Museum, for its part, maintains that it “takes its commitment to be a world museum seriously,” describing its collection as “a unique resource to explore the richness, diversity and complexity of all human history, our shared humanity. The strength of the collection is its breadth and depth which allows millions of visitors an understanding of the cultures of the world and how they interconnect – whether through trade, migration, conquest, conflict, or peaceful exchange.”

Elgin, National Hero or Cultural Plunderer?

The debate about restitution is likely to continue for as long as humankind exists. There is no easy answer to the questions it raises. While some view museums as civic and educational institutions, temples of knowledge dedicated to preserving the best of what humanity has to offer, others, such as Dan Hicks, author of the influential book The Brutish Museums, also recognize their darker side. A side steeped in notions of Western superiority, colonial plunder, and, ultimately, violence. These two perspectives can and do coexist.

Museums have always been, and will continue to be, battlegrounds. Lord Elgin’s legacy is similarly dual, deeply contested, and nuanced. Did he really save the Parthenon Marbles from further destruction, as many of his admirers claim, at a time when many ancient Athenian buildings were in ruins, partially destroyed, and more often than not being repurposed by Ottoman authorities?

Or was Elgin himself part of that destruction, given that the removal process was itself invasive and sloppy? Was he a lover of art or a cultural plunderer? Even if we agree that his acquisition of the Parthenon marbles contributed to a greater appreciation of Greek art and history in Europe, how much of that appreciation and understanding was tainted by colonial attitudes, notions, and economic interests? Did Elgin really receive a firman from the Ottoman authorities, granting him the legal right to measure, draw, and ultimately remove what are now known as the Elgin Marbles? Assuming he did, was his acquisition legitimate, given that Greece was under Ottoman foreign occupation at the time?

Constructed and completed over a period of 15 years, between 447 BCE and 432 BCE, the Parthenon has always been a symbol of all that ancient Greece contributed to the world in terms of art, culture, and democracy, as well as a symbol of modern Greece following its independence from the Ottoman Empire. The Parthenon continues to bridge time and space. The Parthenon Marbles are now considered an integral part of the cultural heritage of both Britain and Greece. They are a reminder of the complex relationship between two societies—the British and Greek—grappling with a troubled shared history and its legacy. So is Lord Elgin—celebrated by some as a national hero, a lover of art, and the man who possibly saved the Parthenon Marbles from destruction—and denigrated by others as a cultural plunderer and a symbol of cultural appropriation.

Bibliography

Salome Kiwara-Wilson, Restituting Colonial Plunder: The Case for the Benin Bronzes and Ivories. 23 DePaul J. Art, Tech & Intell. Propr. L. 375 (2013).

Staffan Lundén, Distorting history in the restitution debate. Dan Hicks’s ‘The Brutish Museums’ and fact and fiction in Benin Historiography, International Journal of Cultural Property, 31: 202-225, (2024).

Dan Hicks, The Brutish Museums. The Benin Bronzes, Colonial Violence and Cultural Restitution, Pluto Press, (2020)