Parents are often warned against spoiling their children, and for good reason. Too much immediate gratification can easily lead to entitlement, a lack of responsibility, and self-destructiveness. This isn’t just conjecture, at least not if we use the life of Pope Leo X as an example.

Born into opulence and handed nearly everything he could have ever wanted on a silver platter, by the time Leo received the “Keys to the Kingdom,” there was little doubt what he’d do with the wealth of the church. What little doubt remained was quickly removed when, upon election to the pontificate, he openly quipped, “God has given us the papacy, let us enjoy it.”

The Noble House of Medici

To understand Leo X, you have to first understand the family he was born into—the House of Medici. A noble family from the Tuscany region of Italy, the Medici grew rich from participating in trade until they amassed enough wealth to open the famed Medici Bank, which at its prime was the largest bank in Europe and made the Medici one of, if not the, richest people on the continent.

Calculating their wealth by today’s standards is tricky, but while some people spend their wealth on houses or fancy clothes, the Medici were on a level of wealth so staggering that they essentially bought the city of Florence itself, amassing so much power that even though they were technically private citizens the city became their personal family fiefdom for many years and provided a base for them to rise to even greater heights later. The Palazzo Medici Riccardi, Palazzo Vecchio, and the Uffizi were all built with Medici wealth and remain some of Florence’s most impressive landmarks even today.

By the time of Leo’s birth in 1475 his father Lorenzo, who was known by the modest title “the Magnificent” was so powerful that he more or less single handedly brought stability to the Italian Peninsula, helped Florence into its Golden Age, and kicked the Italian Renaissance into overdrive, all while dodging assassins and positioning his family for further assured greatness. This power and prestige allowed them to finance their building projects as well as patronize every major Italian Renaissance artist you could name, marry into several royal families, and position four members of their family into the papacy, the first of which would be Leo.

Baby Giovanni, the seventh of ten children, was destined for greatness at birth. His mother reportedly had a dream the night before he was born that she gave birth to a lion, a vision that served as both the inspiration for his eventual papal name and a premonition that seemed to indicate that he was headed for a life in the clergy. With the help of his family’s influence, Leo became an abbot at age seven, the first of 42 offices he would hold before the age of 16. In fact, he became a full cardinal at age 13, a designation that had to be made in secret as he was technically too young to hold such a position, but there were few things that Medici influence couldn’t obtain.

By the time he was 16 and was old enough to officially enter the college of Cardinals and take up residence in Rome, he had already grown accustomed to a lifestyle of extravagance financed by his positions in the church and his willingness to sell offices to his friends and allies.

This behavior must have reached new levels ostentatiousness because his father, a lavish spender and practitioner of political intrigue second to none, was so concerned that one of his last acts on his deathbed was to write his son a letter advising him to turn away from his wicked ways and become more virtuous, tone down his spending on luxurious like silks, jewels, and sumptuous banquets, and try to be more modest in both lifestyle and demeanor warning “there will be many who try to corrupt you.” But Lorenzo made a small miscalculation—his son didn’t require anyone’s help when it came to corruption.

Titanic Fall, Meteoric Rise

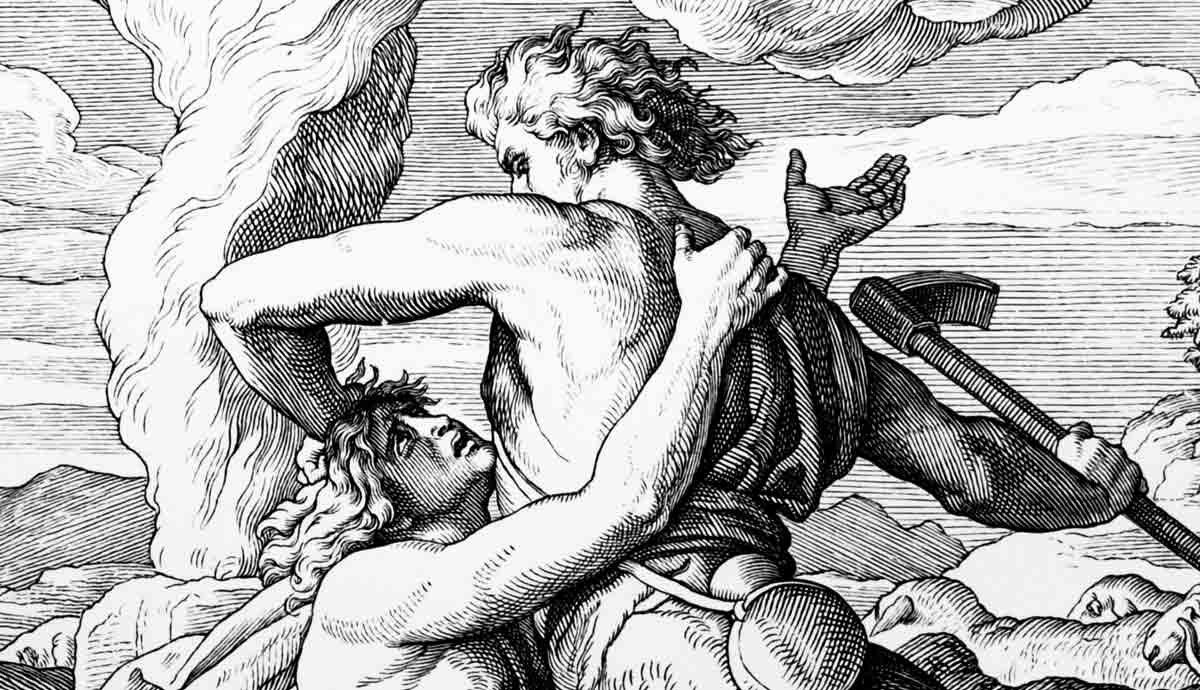

After Lorenzo’s death, power shifted to Leo’s older brother Piero, who lacked his father’s political acumen. This resulted in him bungling a series of political affairs so badly that his family palace was looted and his entire family was driven out of the city in 1494.

With their power base now gone, it seemed like a fool’s bet that Leo would ever become Supreme Pontiff, but several fortuitous events eventually saw him regain all his brother had lost, including a bloodless return to power in Florence after several failed attempts to do so by force.

By 1513, he had regained his family’s wealth and stature just in time for Pope Julius II to die and a Conclave to be called. While he seemed a long-shot candidate at the outset only garnering a single vote during the first ballot, he was able to win the votes of younger members of the College of Cardinals, those who believed that his love of art and literature would make him a more moderate force within the Vatican, and of course thanks to piles of Medici gold being slipped into less than scrupulous hands. When he was finally confirmed in 1513, he remembered the final words of his father and celebrated with only a small, modest gathering.

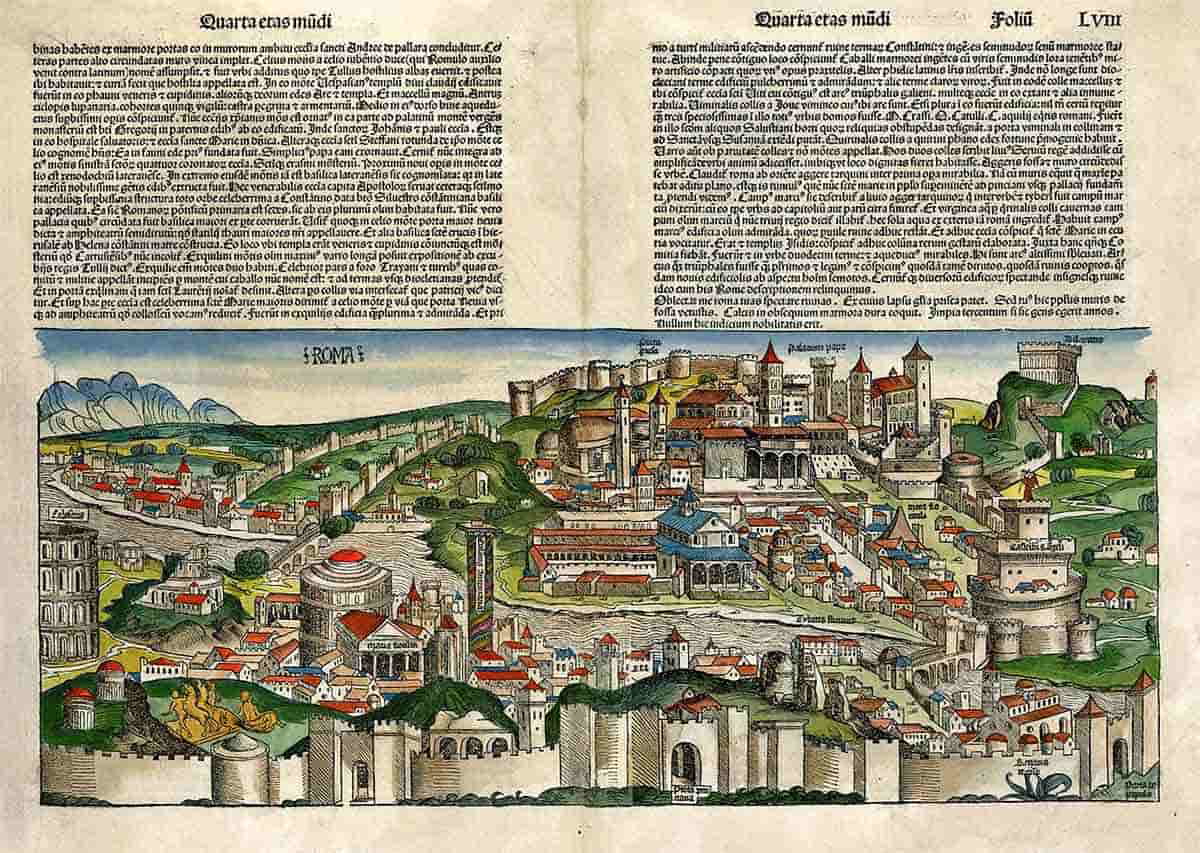

Just kidding. He held one of the most ludicrously over-the-top parades in the history of Rome, complete with newly-built triumphal arches, golden chariots, fountains that spouted wine in place of water, and of course, Leo himself atop a white horse under a canopy of imported silk. And this was only the beginning.

“Let us Enjoy It”

While many members of the church hoped that Leo X would usher in a golden age of reform, he soon proved them all wrong. Right away, he began installing his family into high-ranking positions within the church, including installing one cousin as the new Archbishop of Florence (and would eventually become Pope Clement VII) and another as the Duke of Urbino. He also continued to patronize the arts in the same way that his family had, keeping Renaissance greats like Michelangelo and Raphael on retainer and overseeing the grand renovation of Saint Peter’s Basilica. He was also reported to have donated vast amounts of gold to the poor of Rome. And then there were the parties.

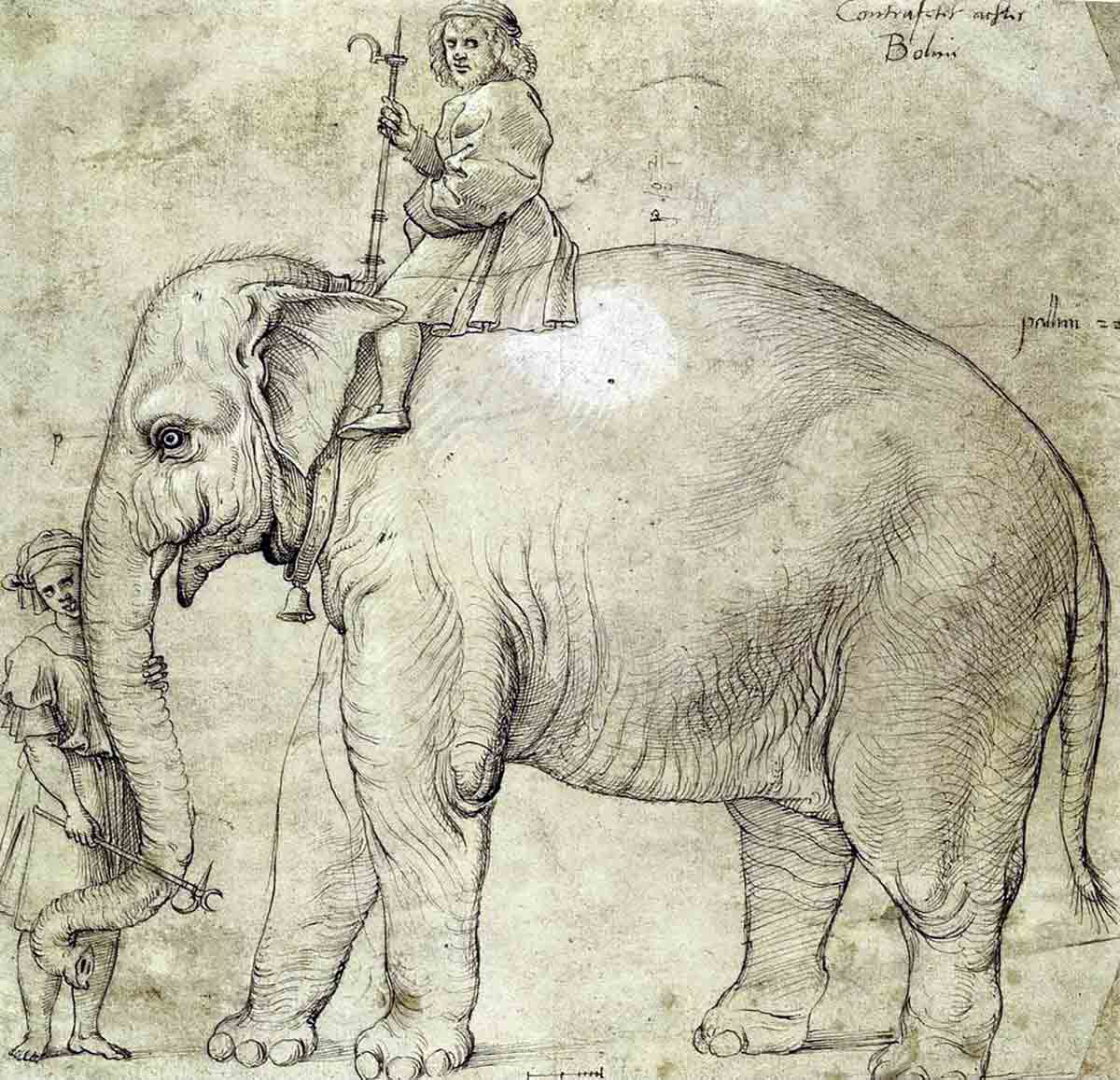

From the outset Leo X’s papal court became legendary for its lavish feasts and what one contemporary called “idle and depraved amusements” including masquerades, hunting trips, and “jests” where he would enthusiastically applaud all kinds of bizarre acts like organizing a fake Roman Triumph led by a burlesque performer who rode Hanno, the pope’s albino elephant.

All of these activities cost money, which he spent at such an alarming rate that before long he had depleted the Church’s funds to such a degree that he began pawning palace furnishings, papal jewels, and even selling off statues of the Apostles. When even this wasn’t enough, he took it one step further and began selling indulgences—payments for the forgiveness of sins. It was this act for which he would go down in infamy, as it put him on a collision course with a German named Martin Luther.

The Protestant Reformation

Even before Leo X became pope, Rome was a circus of vice and corruption, and several smaller reformation movements were smoldering in far-off corners of Europe. But the lavish spending being financed by indulgences was a bridge too far for many, including a German Priest named Martin Luther, who wrote a series of critiques collectively known as the 95 Theses, which, according to popular telling, he ceremonially nailed to the door of All Saints Church in Wittenberg. These writings, dedicated to Pope Leo himself, were disregarded, and after excommunicating Martin Luther it was back to partying.

It isn’t clear if he misunderstood the gravity of what was transpiring, or simply did not care, but either way his inability to grasp what was transpiring in Germany with Luther and his adherents provided much needed oxygen for the launch of the Protestant Reformation, a movement whose political, economic, and social ramifications are too numerous to list here.

His excommunication of Luther turned out to be one of his final acts because, despite his youth, he died in 1521 at the age of 45, leaving a Church that was by most measures teetering on the edge of the precipice. His spending was so out of control that he had actually borrowed against future earnings, meaning that his next two predecessors were hampered by the legacy of his patronage.

While much of that money resulted in the creation of many now priceless treasures of the Renaissance, it also meant that the Church was fighting the Protestant Reformation with one hand tied behind its back at a time when it needed three. The resulting mess left him condemned for all time by many contemporary church scholars like Sigismondo Tizio, who summed up his reign by saying that Leo, “chased nonsense, instead of paying serious attention to the needs of his