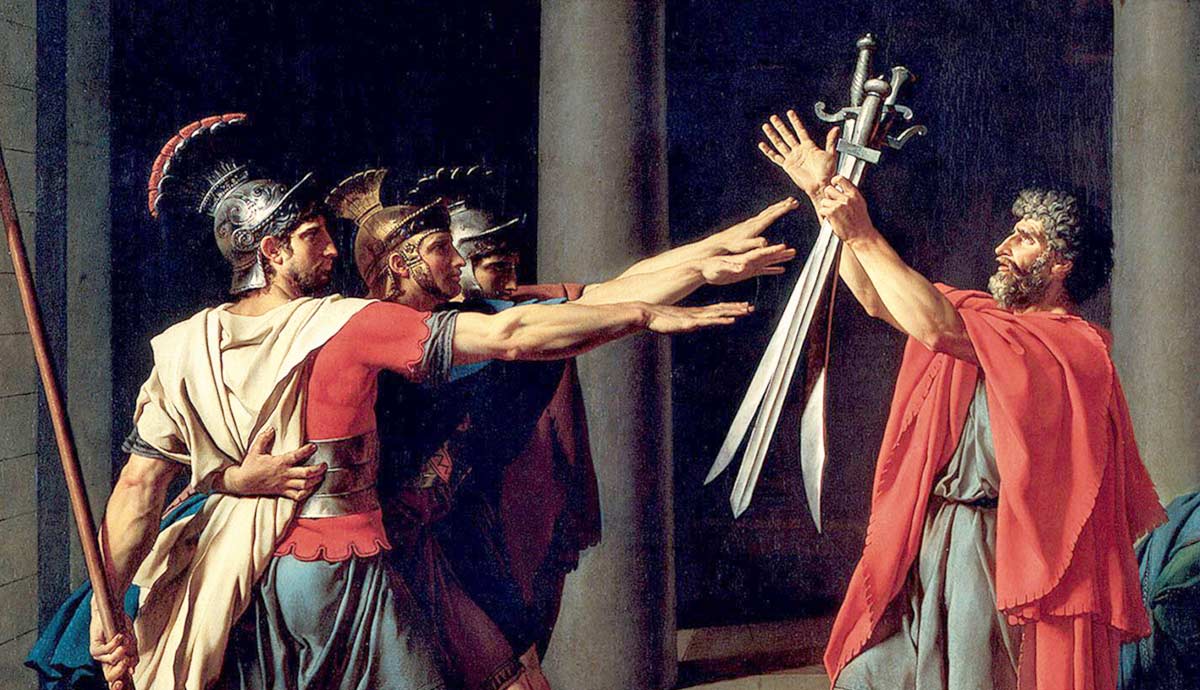

The advocates of the line were admirers of the art of Nicolas Poussin who participated in the classical style. The “colour group” admired the art of Peter Paul Rubens who painted in the Baroque style. By 1717, there was an apparent resolution of the long-running debate in favor of the colorists. The debate itself is an informative insight into perceived relations to the classical tradition, political allegiance, and even philosophical outlook regarding the use of reason and the senses.

Poussin vs Rubens

In the late 17th century, a heated debate developed between a school of thought that held that the drawn line was more crucial to the art of painting, and another view that color was more important. This seemingly academic and inconsequential argument had deep roots and provoked questions about the nature of superior artistic representation.

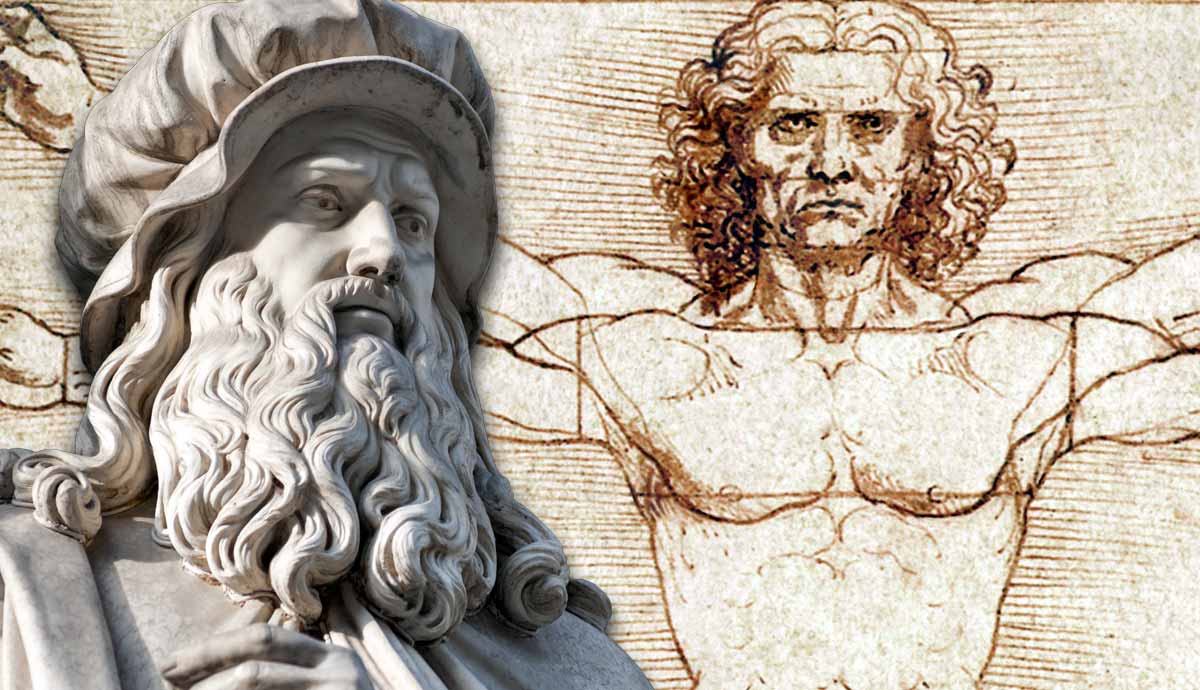

On the one hand were the Poussinists who were classicists in the conventional sense. They believed that the emulation of the forms and atmosphere of the sculpted models of ancient Greece was the highest artistic endeavor and would furnish art with an ideal of perfection.

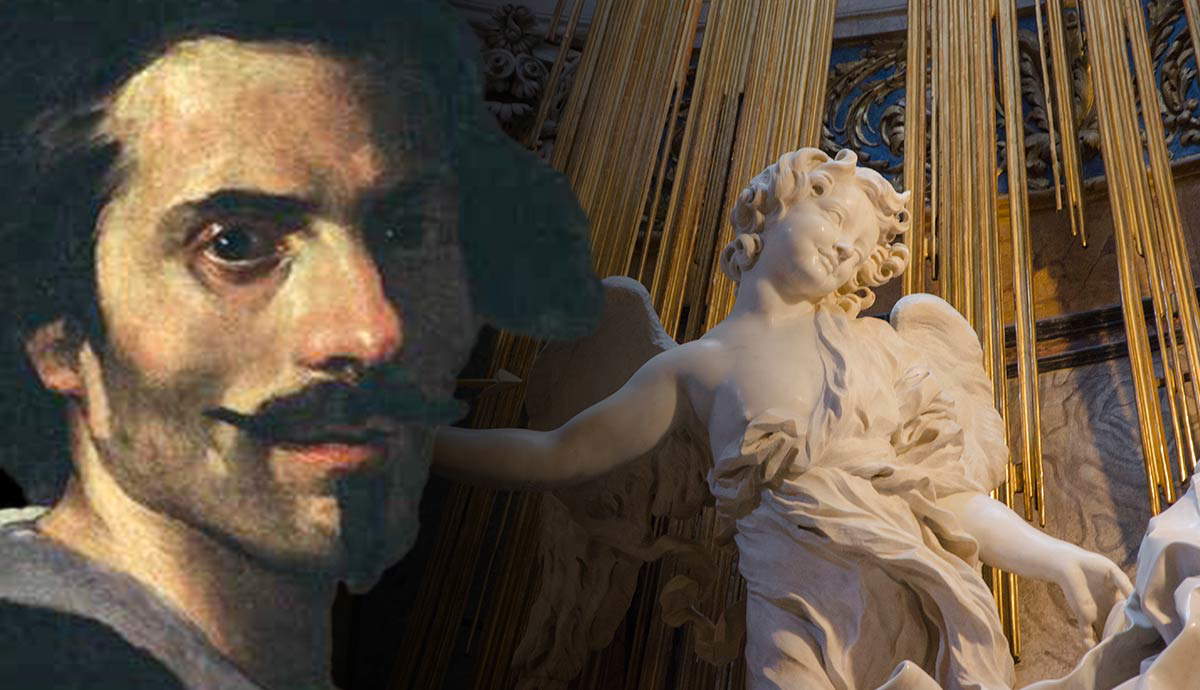

On the other side were the Rubenists who advocated for the naturalistic potential of color prioritized over line. Their objective, as for Peter Paul Rubens himself, was a truthful representation of reality without the imitation of the formal motifs of ancient classical art.

Each side of the argument drew from a deeper metaphysical view of the world and the conditions of consciousness. Also, the dispute crystalized issues of artistic excellence, the nature or possibility of perfection, and the opposition between emulation and naturalism.

The debate raged for several decades after 1671 in the French Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture, a distinctly conservative institution that at least initially was predicated on the principles of the Poussinists. However, by 1717 the Royal Academy made a partial concession that was seen by many as the ultimate triumph of the Rubenists’ aesthetic.

Origins

A contention arose between the Poussinists and the Rubenists in the French Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture in 1671. However, the seed of this disagreement was sown over a century earlier in Rome. There, a dispute occurred in the Academy of San Luca between Andrea Sacchi and Pietro da Cortona, which in some essential ways typified the debate between the Poussinists and the Rubenists of latter 17th century Paris.

Sacchi was critical of what he characterized as Pietro’s exuberance and the excessive decorative detail in his painting. Sacchi also saw in Pietro’s painting a certain diffuseness, as his images contained many figures and various themes. Sacchi was a classicizing painter—his pictures limited the number of figures—and had a more unitary approach to meaning. Meanwhile, Pietro cited his own work as developing multiple themes within one image as a preferable kind of art.

Nicolas Poussin, the inspiration for the Poussinists of the 17th century, was a party to the Roman debate. He took sides with Sacchi and classicism against Pietro da Cortona in these discussions. It was these two styles of painting that were to clash again in 1671, reigniting the controversy. On the one hand, was the classical attitude that was informed by ancient Greek poetic theory and philosophy. On the other side was the Baroque which had more modern affiliations, both in terms of aesthetic theory and philosophy.

The French debate raged on for almost two decades, through 1699, when Roger de Piles—a painter and devotee of Baroque Rubenism was elected as a member of the Royal Academy. This marked a departure for the Academy which was initially resolutely partisan for Poussinism. Institutional victory was finally claimed by the Rubenists in 1717. This was the year of the accession of Antoine Watteau to the Academy for his painting The Embarkation for Cythera.

In this work, Watteau painted an atmospheric scene that prioritized tone and color above the Poussinist line. The picture is expressive and evocative, with the diminutive loosely painted figures engaged in leisure. The principles of classicism are flouted in several ways. The brushstrokes are imprecise in many areas and blended or merely juxtaposed inconsistently. The sensuous details of color, light, and shade are foregrounded by Watteau.

However, the recognition of Watteau’s painting was conditional and incomplete. Since its inception in 1648, the Royal Academy held history painting as the highest genre of art and it maintained this conviction into the 18th century. Accordingly, Watteau was not accepted as a history painter but as “peintre des festes galantes” (a painter of scenes of aristocratic leisure), a category devised especially for him. Watteau’s accession to the Academy was interpreted as a victory for the Rubenists, and it was, albeit qualified.

Poussin’s The Arcadian Shepherds (1637-8) and Rubens’ The Fall of Phaeton (c. 1604-5)

Both Poussin and Rubens were students of the ancients, and both could claim to be classical scholars. Yet their responses to their sources were wildly different from each other.

Generally—and at the height of its power—Poussin’s art can be described as what art critic Joachim von Winckelmann would write in the mid-18th century of Greek statuary’s “noble simplicity and quiet grandeur.” Poussin’s meditative second version of The Arcadian Shepherds of 1638 certainly meets Winckelmann’s description. Poussin’s art was imitative of the art of antiquity, from its carefully delineated figures to his settings in ancient pristine landscapes, and even the quotations of figures’ poses from the ancients. In the case of The Arcadian Shepherds, the stance of the female figure to the right is modeled on that of the Cesi Juno.

In the case of Rubens, his response to classical mythological sources in The Fall of Phaeton is idiosyncratic and more divergent from the conception of antique art in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. However, one famous sculpture which proved so influential to the Flemish artist that he made several sketches of it while in Rome, and can be cited as a stylistic foundation for Rubens’ image. The Laocoon—an ancient Roman copy of a Greek original—is writhing with motion if not violence.

Rubens himself, as a scholar and artist, maintained “It is necessary to understand the antiques, nay, to be so thoroughly possessed of that knowledge that it may diffuse itself everywhere.” He did not see his art as a departure from the legacy of classical antiquity but he did see it as a creative re-interpretation of its original source: the urge to naturalism.

Stephen J. Cody has written that the ancients were so “interested in the sensory experience of the body’s natural texture, that they made the marble suggest living flesh.” It is in this way that Rubens was a classicist. With the ancients, he sought to investigate the phenomena of nature while asserting his own individual aesthetic as a vehicle. It is his individualism—evident in the dramatic sweeps of light, shade, and color in The Fall of Phaeton—that makes him a Baroque artist.

Within the classical tradition, therefore, the Laocoon is part of a current contrary to the inherited conventions of later classicism which championed noble grace, Stoic equanimity, and the primacy of the drawn line. Indeed, Rubens decried the style of painting that prioritized line as an unfortunate consequence of the too-assiduous study of ancient sculpture. He argued that painting should not “smell of stone.”

Rubens’ response to classicism did not demand the stylistic emulation of the tradition as it recurred during the Renaissance. His response was individualistic and his ethic, naturalistic. His Baroque pictures were full of movement intensified by the quick and loose application of paint.

The solidity of forms and figures in Poussin’s The Arcadian Shepherds, and the primacy of outlines make for a materiality and presence. Poussin’s colors are muted so as not to distract from his theme of mortality. The solid materiality of the tomb is inscribed with “Et in Arcadia ego.” This means either the occupant of the tomb is speaking, or Death is speaking. The occupant says “I, too, lived in Arcadia,” but if the inscription is translated as “I, too, live in Arcadia,” the theme of general mortality is invoked.

The tomb—a pure unyielding object of stone—is central in the image. Its stark and sheer lines speak of inevitability, the passage of time, and the pervasiveness of death, even in a pastoral paradise. The image is both commemorative of the dead and forward-looking to the ultimate mortal moment. But Poussin also paints the present, the discovery of the tomb by the shepherds, and their reading of the inscription as an occasion for quiet reflection. Death is present in the sense of the inscription and in the stone of the tomb. By virtue of this, it is itself made material.

By contrast, in The Fall of Phaeton, Rubens is painting motion as much as figures in motion. His image shows a flux rather than any of the heavy substance of the Poussin. The shape of the cascading figures is an oval, the shape of a seemingly unending vortex. These figures, including Phaeton helplessly falling from his father Helios’s chariot, are caught up in chaos. The oval also proves a counterpoint to the great “wheel” or crystalline sphere of the heavens on the left—itself momentarily strained before the restoration of the heavens.

Rubens does paint his figures with substance and weightiness, but as much as he does so, he also paints the chaotic motion of the vortex that is more startling for the materiality of his figures. He therefore reveals the power of Zeus and his thunderbolts all the more sublime.

The sublimity of the image is by way of inference—Rubens does not paint the person of Zeus but rather paints his power abstractly with a dynamic interaction of light and shade. Brilliant gold and darks sweep across the canvas in a great expressive gesture that threatens to flood out into the world of the beholder. The thunderbolts and the fluctuations of light and shade are loosely painted as if inviting the imagination to feel the awe of a bottomless sublime.

The turmoil in the expressions of Phaeton, the Hours, the Seasons, and the horses are testament to the dreadful power of the gods which is only suggested by their terror.

Rubens proceeds by intimation and open suggestion without statement. Poussin’s painting is self-contained. His tomb is central, the shepherds are gathered around it, and the light also falls on them while on either side the distant landscape is dimly lit. Rubens’ primacy of tone and color, and his exploration of the capabilities of hues to dematerialize a scene—even when his figures have a sculptural substance—provide in the Phaeton picture a world of vicissitude and chance. Poussin’s world is circumscribed by strong lines and as such is far more certain and substantial, evoking a permanence.

The Aesthetic, the Political, and the Philosophical

The debate between Poussinism and Rubenism in the later 17th century was not merely a debate about whether line or color should dominate in the ideal painting. The line-color dispute was the surface appearance of the disagreement and the manifestation of a fundamental difference both politically and philosophically.

The adherents of the overtly classical art of the mature Poussin were also seen as adherents, by and large, of the French royal establishment. Their version of classical art, with its textual and visual influences from antiquity and the Renaissance, required a learned and informed audience. Their insistence on formal structure, compositional and gestural quotation, and all of this being affected by the “sculptural” line, was seen as elitist and an art for scholars.

Rubensian art, on the other hand, was not textual. It focused on the expressive potential of color, and on drama. This version of Baroque painting was readily accessible to a wider audience who were not necessarily acquainted with the ancient literary or artistic models. Rubens’ art was more sensuous, more easily understood, and was thus seen as more egalitarian.

The line-color dispute was also rooted in a fundamental philosophical divergence between idealism and empirical naturalism. Poussinism—and much of classical art—was based on an idealization of form. This was done according to the antique stipulation that the best objects and figures are to be arrived at through the selection of elements from nature with the use of reason. At base, this conception of the ideal is derived from Plato and his contention that the objects and attributes of the world are imperfect versions of their ideal “Forms,” such as “beauty” or “the good.” The Poussinist tradition participated in this worldview. The drawn line was seen as the quintessence of the operation of reason in art, which was to combine nature’s diverse elements and produce an approximation of the ideal form.

Rubens’ art was, as noted, sensuous and of this world. His painted figures are heavy and fleshy. More than anything he painted physical sensation. His art is firmly attached to the empirical world, and he could find a philosophical justification in the position of John Locke among others. These empiricist thinkers maintained the tabula rasa idea—that there are no innate ideas, nor ideal Forms. Instead, they opined, that everything is derived from sense experience.