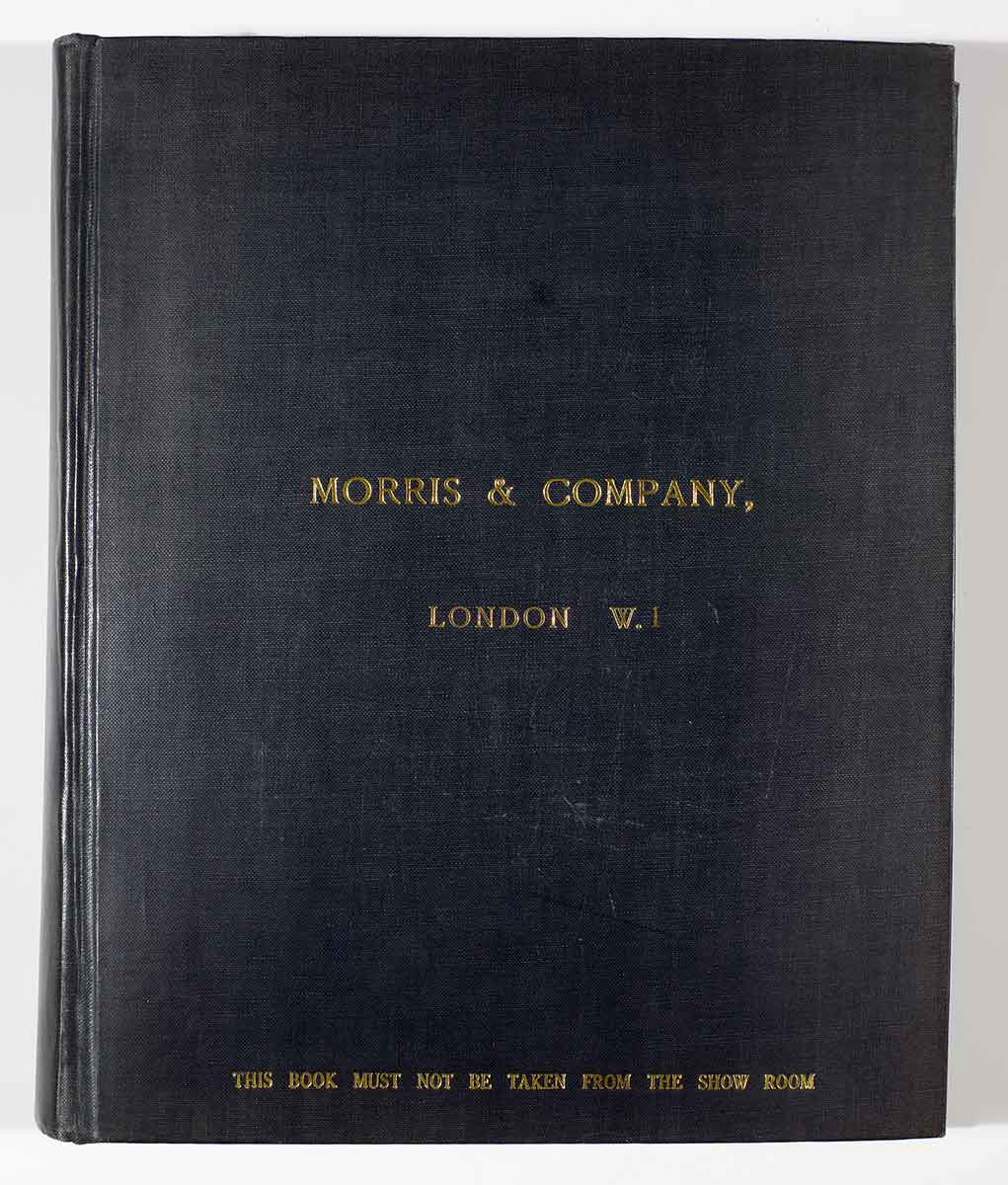

A direct response to the technological onslaught of the Industrial Revolution, the Arts and Crafts Movement championed a return to the traditional craftsmanship of the medieval period. Its leader was William Morris, who led the charge with his business Morris & Co. Initially known as Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co., the business created a wealth of stunning interior spaces decorated with its own handcrafted wallpaper, furniture, and other decorative arts pieces. Morris himself was directly inspired by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, a leader of the Pre-Raphaelite movement.

A Pre-Raphaelite Mentor to Arts and Crafts Movement’s William Morris

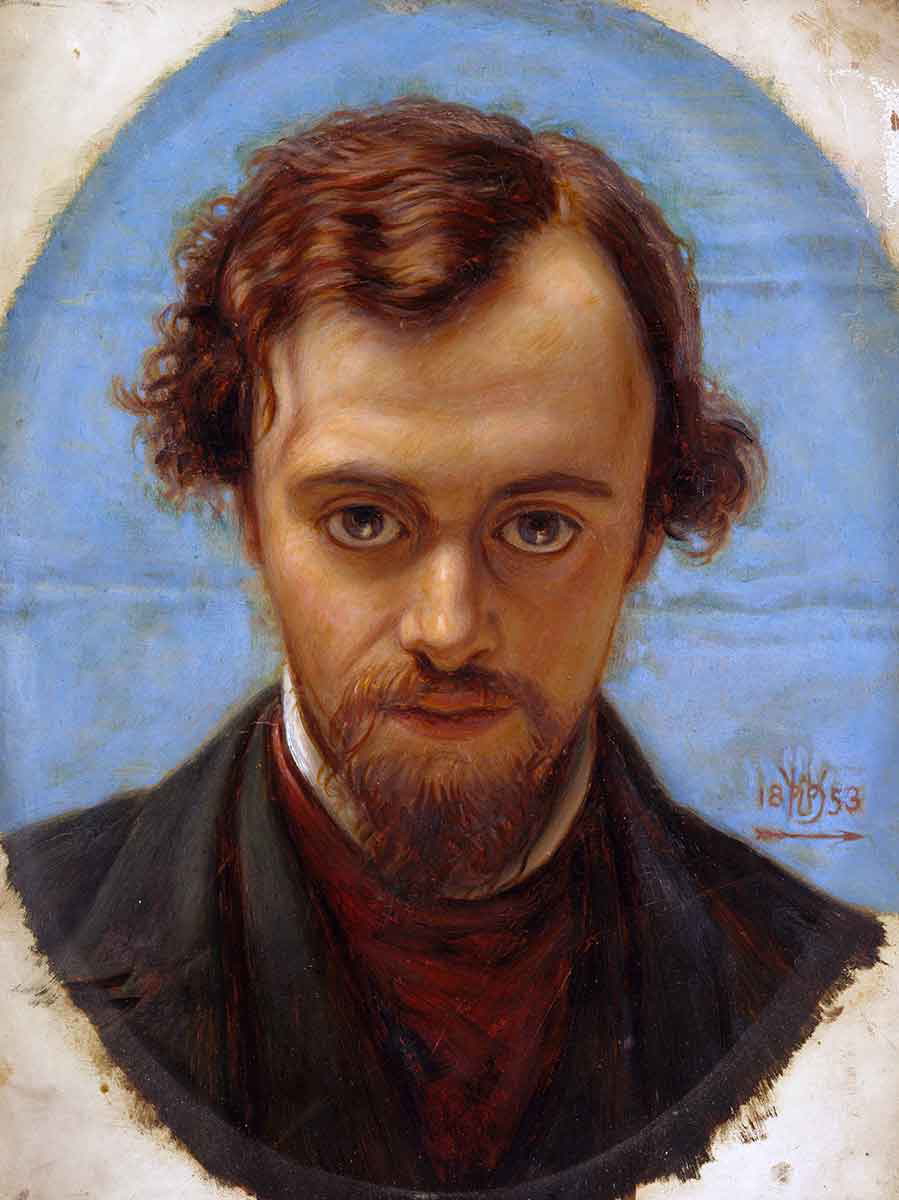

Dante Gabriel Rossetti was one of the most influential artists of the 19th century in Great Britain. Born in 1828 as the son of an Italian poet and politician, Rossetti helped to found the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in 1848 while studying at the Royal Academy of Arts in London. Along with his friends and fellow students William Holman Hunt and John Everett Millais, Rossetti sought a return to an authenticity in art that he felt had been lost since the Italian Renaissance. This attitude towards art would put Rossetti at odds with England’s official art establishment, resulting in his early Annunciation painting Ecce Ancilla Domini! being harshly criticized. Even though Rossetti refrained from holding exhibitions of his works after this, it did not keep his creations from gaining popularity through personal visits to his studio and word of mouth.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s works of art came to typify Pre-Raphaelite medievalism and beauty, transporting viewers into a world of wonder and enchantment. Often depicting scenes from medieval literature, other times recounting simple morals in visual form, his powerful art propelled him forward as a leading Pre-Raphaelite artist. His attitudes towards beauty in women were particularly important for the Pre-Raphaelite movement, differing from the prevailing attitudes of his time, in which restrictive corsets and severe updos were typical. Rossetti’s fascination with a different type of model could be seen early on in his career through his relationship with his wife, Elizabeth Siddal, whose striking auburn hair and otherworldly features strongly attracted Rossetti. Siddal’s unique looks provided an endless source of artistic inspiration to Rossetti until her death in 1862, and went on to become the cornerstone for the artist’s ideal model.

When Morris Met Rossetti

In light of this information, it is easy to understand the powerful effect Rossetti’s vision and presence would have had on younger artists in the 19th century. One artist who was particularly affected by the larger-than-life Rossetti was William Morris. A young man of well-to-do origins, Morris was a theology student at Oxford University in the 1850s. While at Oxford, Morris was dazzled upon viewing works of art by John Everett Millais and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and lost interest in the church as he became enthralled by art. Abandoning a prestigious apprenticeship to an architect after completing his studies, Morris decided to become an artist and work more closely with Rossetti. This was the beginning of a long relationship between Morris and Rossetti that would have a permanent impact on Morris’ artistic output.

In 1857, Morris began collaborating with Rossetti on a set of murals for the Debating Hall of the Oxford Union. This was very much a project led by Rossetti, who had received the initial commission and had conceived that the theme of the murals be Arthurian legend rather than the proposed topic of scientist Sir Isaac Newton. Under Rossetti’s guiding hand, Morris began to explore his own artistic vision here as never before. Here, Morris combined his architectural and artistic knowledge, creating ornate painted patterns on the upper sections of the building of the Debating Hall.

Even his completed mural, Sir Palomydes’s Jealousy of Sir Tristram, contained an abundance of decorative sunflowers, showing a taste for floral patterns that became a defining feature of his work later in life. The Arthurian legends that Rossetti had chosen for the theme of the murals, as well as Rossetti’s character-driven approach to them, were also influential for Morris. Morris surely took note of the drama of Rossetti’s approach to the murals, such as in Rossetti’s Sir Launcelot prevented by his sin from entering the Chapel of the San Grail, and took a similar approach to some of his most important works in the Arts and Crafts movement.

Explorations in Decorative Arts

As Morris began to solidify his views on fine and decorative arts, Rossetti remained an important mentor and collaborator to the younger artist. This continuation of their relationship was manifested in Red House. Red House was a home that Morris had constructed towards the end of the 1850s for himself and his wife Jane Morris, whom he had met during the creation of the Oxford murals. Red House embodied many of the principles that would come to define the Arts and Crafts movement, flaunting its handcrafted features in defiance of modern architectural standards, and featuring charming bespoke rooms carefully cultivated by Morris. The interior design of the house had a distinct medieval flair, an interest that Rossetti had helped Morris to develop.

Rossetti assisted Morris in making his medieval visions a reality at Red House. For example, Rossetti created a series of beautiful paintings in his distinctive Pre-Raphaelite style for a settle Morris had designed. The settle was originally intended to be a furnishing for Morris’ London studio at Red Lion Square, but its final home was Red House. The paintings on the settle were inspired by La Vita Nuova by Dante Alighieri, an Italian poet of the 13th and 14th centuries close to Rossetti’s heart, and specifically featured scenes between Dante and his beloved Beatrice. This merging of the sentimental and medieval styles of Pre-Raphaelite art with the tangible form of the settle was a very important step towards the Arts and Crafts pieces that Morris would go on to create.

The Founding of the Firm

Dante Gabriel Rossetti also maintained a presence during one of the most significant moments of Morris’ career, the founding of his business in 1861, originally known as Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co. This business was conceived in the aftermath of Morris’ scheme at Red House, which had articulated his unique vision of interior design, celebrating traditional craftsmanship over modern mass production. Craftspeople at Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co. created the company’s products through archaic processes that the Industrial Revolution had threatened to render obsolete.

The company was a pioneer in the Arts and Crafts movement, with Morris personally overseeing its production and planning the decorative schemes it offered clients. Rossetti, ever passionate about finding ways to infuse both fine and decorative arts with an authentic and medieval spirit, was enthusiastic about the business. Serving as a founding member of the company, he convinced other artists in his Pre-Raphaelite circle to assist in the endeavor, including Ford Madox Brown and Edward Burne-Jones. In this way, Rossetti, with his beliefs in the necessity of taking inspiration from times past to create great art, can be said to have laid the groundwork for Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co. to take flight as the figurehead of the Arts and Crafts Movement.

The Pre-Raphaelite Influence of Morris & Co.

Many of the most important works of Morris’ firm, today known as Morris & Co., trace their origins to the Pre-Raphaelite style that initially inspired William Morris at Oxford. Working alongside other artists from the movement, Burne-Jones and his collaborators created works that paid homage to Rossetti and the Pre-Raphaelite movement while at the same time celebrating the specific values that defined the Arts and Crafts Movement. For example, the company’s “Jasmine” wallpaper of 1872 immerses viewers in a detailed vision of jasmine flowers and hawthorn leaves, celebrating natural beauty and lifting up a simple and authentic ideal. This type of design, with its heavy emphasis on natural patterns that seem to dance across a wall, was a common theme in many of the wallpapers Morris & Co. created.

Pre-Raphaelite influence can be especially felt in the Holy Grail tapestries which the company created for the oil magnate William Knox D’Arcy’s dining room at Stanmore Hall in the 1890s. The final tapestry of the series, The Attainment, particularly stands out as one of Morris’ greatest successes. In this scene, the knight Sir Galahad kneels before the Holy Grail, the titular artifact that he and his fellow knights of the Round Table have been searching for throughout the series. He holds a bunch of lilies in his hand, a traditional flower associated with purity, while being greeted by a trio of angels.

The image comprises an immersive medieval world, in which characters are adorned in Arthurian armor and textiles, and the Grail is housed in a Gothic structure. The implication of this visual imagery seems to be that the purity of Sir Galahad can only be achieved by focusing on what is simple and true, with the medieval setting entrenching Sir Galahad in a world reflecting his nature. Such a symbolic work of art seems to have been heavily inspired by Morris’ experiences at the Oxford Union, with his character-driven approach being inspired by what he had learned from Rossetti.

Rossetti’s Lasting Mark on the Arts and Crafts Movement

Many of the ideas that Rossetti transmitted to Morris were impactful for other leading figures in the Arts and Crafts Movement. They can be seen specifically in the art of Walter Crane. Crane was an important leader in the Arts and Crafts Movement, even helping to establish the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society in the late 1880s and serving as its first president. He had also collaborated with Morris to create illustrations for Morris’ Gothic-inspired publishing house, Kelmscott Press. Of all Crane’s works, his 1905 triptych The Briar Rose seems to embrace the Pre-Raphaelite legacy that the Arts and Crafts Movement had inherited most especially. Like the Pre-Raphaelite works discussed so far, the triptych recounts a mythical tale, the famous fairytale Sleeping Beauty.

In the manner of the Oxford murals and Holy Grail tapestries which preceded it, The Briar Rose immerses its viewers in a medieval world, complete with detailed costumes for characters and majestic Gothic backgrounds. In the paintings that make up the triptych, Crane attempts to accomplish on canvas what William Morris accomplished at Red House. Indeed, the triptych celebrates handcrafted works, with a carefully carved lute and detailed embroideries in the princess’s bedchamber. In the third panel, it is possible to see a lady of the palace embroidering, drawing attention to her individual skill with a needle.

Another colleague of Morris’ in the Arts and Crafts Movement, William De Morgan, also was impacted by the legacy of the Pre-Raphaelites. De Morgan worked at Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co. for a time, and eventually decided to begin his own ceramics manufactory in 1872. Even after De Morgan began his own business, Morris sold De Morgan’s products at Morris & Co. De Morgan also frequently drew inspiration from medieval sources, such as the medieval Islamic pottery that provided the driving force behind his approach to glazes. While De Morgan experimented with different types of medievalism than Morris and Rossetti did, works such as the charger displayed above demonstrate a love of natural imagery and an embrace of pattern that the Pre-Raphaelites also shared.