Here are just five of the many iconic quotes by Queen Elizabeth I. In this article, we will retell some of the fascinating stories of her life and then attempt to discover the hidden meanings behind her most famous words.

Elizabeth I: The Wise Words of a Tudor Woman

When considering the most frequently quoted phrases in British history, there are many influential and eloquent figures whose words immediately spring to mind. The Duke of Wellington, for example, notably claimed that “the Battle of Waterloo was won on the playing fields of Eton.” A little earlier, Samuel Johnson declared that “he who is tired of London is tired of life.” Most recently, Winston Churchill gave his inspiring wartime speech, in which he immortalized the stirring words, “We will fight them on the beaches.”

However, it is not only great men, but also great women, who are responsible for coining some of the most powerful quotes ever uttered. Queen Elizabeth I, who ruled England between 1558 and 1601, is one such female figure whose words have endured the centuries.

Elizabeth reigned for over four decades, and so successful was her time on the throne that it has since become known as the Golden Age. During this time, Elizabeth spoke wisely on many topics, just a few of which will be explored in this article.

1. On Her Succession to the Throne

“This is the Lord’s doing, it is marvellous in our eyes.”

When the joys and burdens of queenship fell upon her in November 1558, Elizabeth Tudor was just 25 years old. Although this may seem a young age to cope with such great responsibility and to wield such great power, her youth would not have been an issue that many thought important or even relevant. King Henry V, whose reign was still remembered fondly as one of the most successful, had also inherited his father’s throne at the age of 25. Furthermore, many of Elizabeth’s predecessors had begun their reigns in their teenage years or even childhood. The list of British history’s younger Monarchs includes her father, King Henry VIII, who turned 18 just a few days after his coronation. Other notable ages for succession and successful rule, up until this point in history, include nine (King Henry III), 14 (King Edward III), and 18 (King Edward IV).

Despite her young age and her supposedly weak gender, Elizabeth was ready to rule, and had been for quite some time. So intensely had this moment been awaited that she had even prepared herself with a short but meaningful speech. What could be more important than her first sentence spoken as Queen of England?

Those who surrounded Elizabeth would have been ready to capture her words, note them down, and hastily spread them across the country. Elizabeth was an intelligent and shrewd young woman; she would have known that her reaction to her sister’s death would be a source of anticipation to many. For this reason, it was appropriate for Elizabeth to have something ready to say, rather than risk being caught off guard.

It was on the 18th day of the month that Elizabeth finally had the chance to deliver her chosen words. After a reign of just under five years, Queen Mary I had died at St James’s Palace in Westminster. There was only one realistic heir, and that heir was immediately proclaimed the new Queen of England.

Later that same day, the news was brought to Elizabeth at her residence, Hatfield House in Hertfordshire. On hearing that she was now Queen, she fell to the grass beneath her feet. “This is the Lord’s doing,” she said, “it is marvellous in our eyes.” Some historians think that she would likely have spoken the words in Latin: “A domino factum est istud, et est mirabile in oculis nostris.” Either way, there is no mistaking where the quote originates. This significant sentence can be found in the Bible, towards the end of the Book of Psalms. Psalm 118, to be exact.

The quote has many variations and may differ according to which translation of the Bible is being used. “This is the Lord’s doing; it is marvellous in our eyes,” or something similar, can be located precisely in verse 23.

Psalm 118 was (and still is) a popular choice of Psalm for many occasions. It is often especially selected for its beautiful expressions, its themes of thanksgiving, and its promotion of the reliance of humankind on God alone.

The psalm is attributed to King David and was possibly composed to celebrate either a military victory or a deliverance from some hardship. Elizabeth may very well have felt this psalm reflected her own situation, a permanent end to the difficulties she had faced during the reigns of her brother (Edward VI) and her sister. “It is marvellous in our eyes,” hardly expresses grief over the loss of a beloved family member. On the other hand, it is important to remember that the word “marvellous” was not used in the same way then as it is now. By using the word “marvellous,” Elizabeth was insinuating that her accession was mysterious, wonderous, and something to be marveled at.

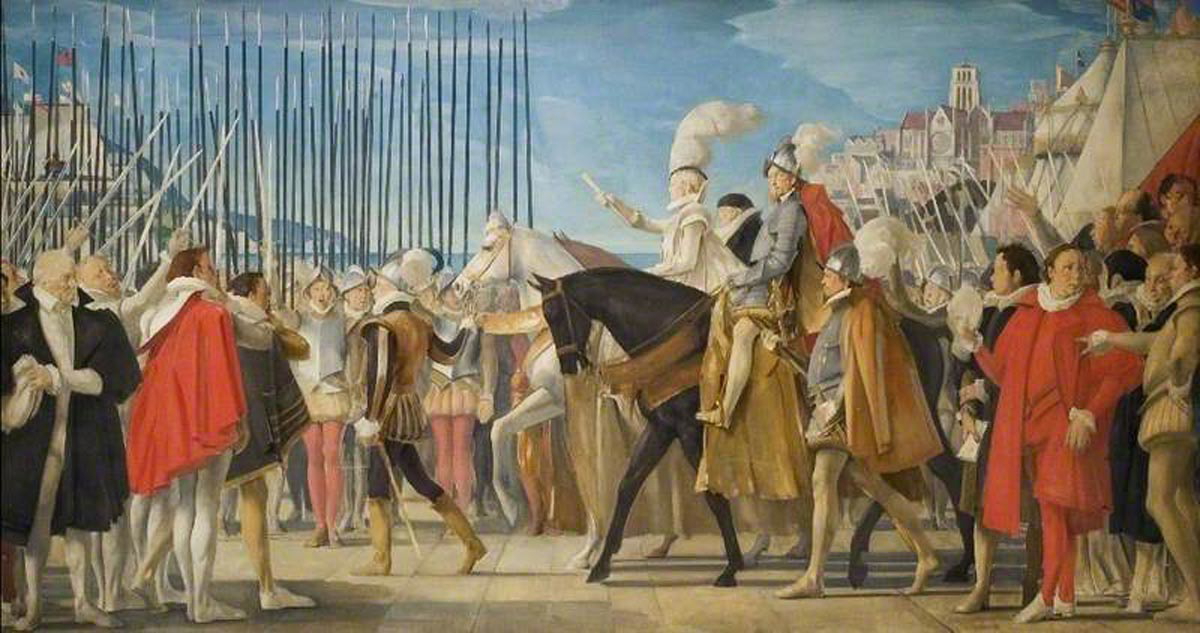

It wasn’t just Elizabeth who thought well of the Lord’s doing. A large percentage of the common people in England were delighted with the prospect of a Protestant Monarch. The Encyclopaedia Britannica tells us that “she came to the throne amid bells, bonfires, patriotic demonstrations, and other signs of public jubilation. Her entry into London and the great coronation procession that followed were masterpieces of political courtship.”

On Elizabeth’s entry into London, one admirer noted that “if ever any person had either the gift or the style to win the hearts of people, it was this Queen, and if ever she did express the same it was at that present, in coupling mildness with majesty as she did, and in stately stooping to the meanest sort.”

2. On Religion

“I would not make windows into men’s souls.”

When it comes to the many quotes of Queen Elizabeth I, this is certainly one of the most cryptic. Its tone is somewhat more mysterious than that of her other well-known sayings, and its meaning may not immediately be clear to all who read or hear it. Nonetheless, Elizabeth made this oblique declaration at the very beginning of her reign. Upon assuming the crown, Elizabeth allegedly declared that she “would not make windows into men’s souls.”

By this, Elizabeth meant that she did not mind what people thought or believed regarding the Bible or the Church. By refusing to “make windows into men’s souls,” Elizabeth showed that she would not attempt to pry into the hearts and minds of her people, but would allow each individual to come to their own conclusion regarding the theology of the Church of England.

This in itself was a huge step forward for the Christian faith in Britain. After four decades of religious tyranny (particularly from King Henry VIII and Queen Mary I), a more tolerant monarch may have been a welcome relief for Catholics and Protestants alike. Elizabeth herself has become famous for being a Protestant Queen (like her mother and sometimes her father), and so long as her country was Protestant on the outside, she would not condemn her people for the ideas and beliefs they kept inside.

As with many of her quotes, it is not known for certain that Elizabeth actually said the words aloud. One record of the phrase can be found in the letters of Francis Walsingham. In a note to Sir Frances Bacon, he said the following: “Her Majesty, not liking to make windows into men’s hearts and secret thoughts except the abundance of them did overflow into overt and express acts or affirmations, tempered her law so as it restraineth only manifest disobedience, in impugning and impeaching advisedly and maliciously her Majesty’s supreme power, and maintaining and extolling a foreign jurisdiction.”

This mention of Elizabeth’s decision (“not liking to make windows into men’s hearts and secret thoughts”) seems to attribute the quote to her directly. But was Walsingham quoting words he had heard from her own mouth? Was he repeating what other courtiers had reported? Or did the words actually originate from him?

Unfortunately, we will never know. However, this quote remains important to the modern-day historian as it highlights Elizabeth’s unprecedented religious tolerance.

3. On Marriage

“I will have but one mistress here and no master.”

Elizabeth I is famously remembered as the Virgin Queen. In 1559, in the midst of a speech to parliament, Elizabeth declared her intentions to remain unmarried, “This shall be for me sufficient,” she swore, “that a marble stone shall declare that a Queen, having reigned such a time, lived and died a virgin.”

Elizabeth stood by her word. She never married, and she supposedly (though it is considered extremely unlikely by many historians) remained a virgin until her death in 1603. Elizabeth purposely defied the expectations of her era by refusing to take a husband. Obviously, a consequence of her decision to remain unmarried was that she could produce no heirs to her throne.

This is not to say that she did not have marriage suitors. Just a few of the men proposed for her hand were King Phillip II of Spain, King Eric XIV of Sweden, Archduke Charles of Austria, and Francois Duc d’Anjou. Elizabeth entertained the idea of marriage to these men at various points throughout her reign, but never went through with any of the plans.

Despite this, Elizabeth was rumored to have enjoyed romantic relationships with various men, most notably Robert Dudley. He was also known as the Earl of Leicester, and is still popularly believed to have been the love of Elizabeth’s life. It was Robert Dudley at whom this quote was aimed.

This quote of Elizabeth’s is different from all the others, and its difference is what makes it so special. This is because it was said on a whim, in the heat of the moment. “I will have but one mistress here and no master,” was firmly stated by Elizabeth during an intense argument with Robert Dudley. Perhaps with the desire of causing him envy, Elizabeth had been showing particular attention to other gentlemen at her Court. Robert Dudley complained to her about her affection for other men, and a squabble ensued.

The nature of this conversation means that Elizabeth’s words weren’t planned, but were spoken in a rush of anger. This quote comes from Elizabeth the woman rather than Elizabeth the Queen. Here, while shouting at her possible lover before a room of shocked courtiers, Elizabeth displays the emotion that any woman might feel in the midst of an argument with the man she adores.

In its full version, the quote is slightly longer: “God’s death, my Lord, I have wished you well, but my favour is not so locked up for you that others shall not participate thereof. And if you think to rule here, I will take a course to see you forthcoming. I will have but one mistress here and no master.”

4. On War

“I know I have the body of a weak and feeble woman, but I have the heart and stomach of a King.”

Of all the quotes attributed to Queen Elizabeth I, this is undoubtedly the most famous. These words were first composed as part of a longer oration known as the Speech To The Troops At Tilbury, which was said to have been delivered by Elizabeth on August 9, 1588. The aim of her speech was to inspire her English troops, in preparation for the fast-approaching invasion by the Spanish Armada.

But how do we know what Elizabeth said at Tilbury? Well, there are four notable versions of the speech, all of which were recorded at various points over the century that followed.

The first record of the Speech at Tilbury was taken by a man called Leonel Sharp (1559-1631), a Chaplain to Robert Devereux and a friend of Robert Dudley. Sharp was present at Tilbury camp at the time the speech was delivered. This is good for news historians—it means anything he wrote about his time there can be considered a primary source. Sharp was chosen to repeat Queen Elizabeth’s oration to the whole army assembled there. He was also responsible for recording the speech on paper and beginning its circulation.

Some years after the battle, a transcript of the speech was discovered in a letter from Sharp to the Duke of Buckingham. It is this version that is widely considered to be the most authentic. In 1654, over 60 years after the speech was delivered, Sharp’s record was published in a collection titled Cabala, Mysteries of State.

Another version of the speech was recorded in 1588. This lyrical poem, entitled Elizabetha Triumphans, was published in 1588 by a writer named James Aske. Although it was written in the same year the speech was delivered, it cannot be considered accurate as it was purposefully reworked into a work of literature, rhyming and in iambic pentameter, to be read for pleasure rather than inspiration.

A third version of the speech was recorded in 1612 by the English preacher William Leigh (1550-1639). His record is much shorter and includes some passages in Latin.

Due to the somewhat unreliable nature of these versions, the authenticity of the Speech at Tilbury has been debated by historians, particularly over the last two centuries. When analyzing our versions of the speech, there are three questions to be answered. Firstly, did Elizabeth really deliver this speech at Tilbury? Secondly, if she did, how accurate are our transcripts? It seems unlikely that they provide a word-for-word account of what was actually spoken. Thirdly, did she compose the words herself, or were they written for her by an advisor?

Many historians consider the speech unreliable, believing it to have been altered or fabricated over time. The historian David Loades, for example, was somewhat sceptical. He wrote, “whether she used these words we do not know, although they have an authentic, theatrical ring.”

On the other hand, the Speech at Tilbury has been accepted as reliable by many historians, including J.E. Neale. He claimed that he saw “no serious reason for rejecting the speech.” He explained that the words sounded like something Elizabeth herself would have written; “some of the phrases have every appearance of being the Queen’s, and the whole tone of the speech is surely very much in keeping [with her other quotations].”

It is hardly difficult to believe that Elizabeth’s words were her own, for she was known to compose her own speeches, and even to write poetry for her own enjoyment.

With this particular section of the speech, Elizabeth paints herself as a king, and highlights her bravery, her power, and her skills in leadership. Elizabeth’s self-depiction as a king rather than a queen was a common theme throughout her reign. On many occasions, she referred to herself as a prince rather than a princess.

5. On Death

“All my possessions for one more moment of life.”

Despite her Christian faith, Queen Elizabeth I was famously terrified of death. It was in March of 1603, at the age of 69 and after a reign of 44 years, that she was finally made to face her greatest fear. She became extremely unwell. It was clear to everyone, including her, that she would not recover. It is said that, having succumbed to her sickness, she remained in “a settled and unremovable melancholy” for hours on end. Towards the end of her life, she sat motionless on the floor at the end of her bed, with only a cushion for comfort.

When Robert Cecil told her that she must go to bed and sleep, her reply was short, “Must is not a word to use to princes, little man,” she informed him. The reason for Elizabeth’s refusal to go to bed has been speculated over the last four centuries. Elizabeth knew she was likely to die. Maybe she thought that if she went to bed or went to sleep, she would not get up again.

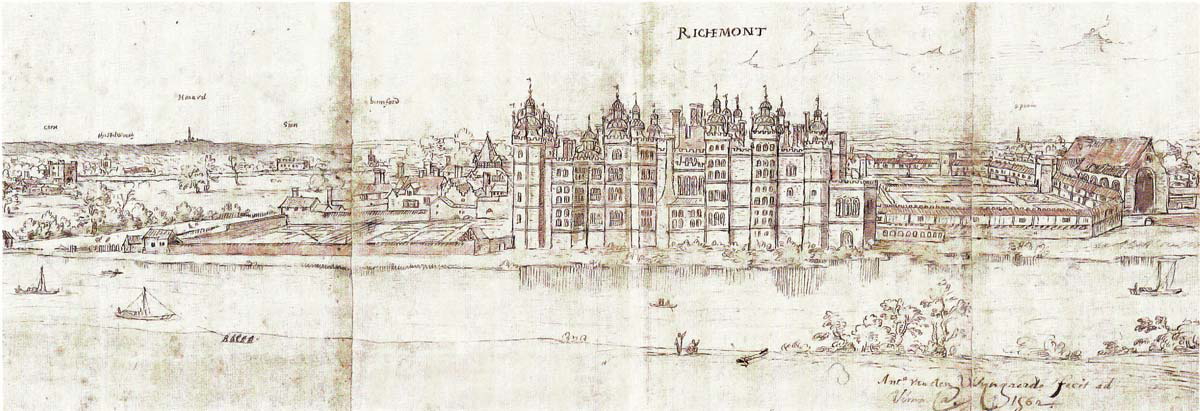

Elizabeth died at Richmond Palace on March 24 that same year. A few hours later, King James VI of Scotland was proclaimed as King James I of England.

Elizabeth’s last words were thought to have been, “All my possessions for one more moment of life.” Although the quote is well known, its authenticity is doubted. Some historians believe the story of Elizabeth’s last word is fabricated or even apocryphal.

The body of Queen Elizabeth I now lies in Westminster Abbey in London. She shares her final resting place with her half-sister, Queen Mary I, and the Latin inscription on their tomb reads: “Regno consortes & urna, hic obdormimus Elizabetha et Maria sorores, in spe resurrectionis,” this translates as, “Consorts in realm and tomb, here we sleep, Elizabeth and Mary, sisters in hope of resurrection.”