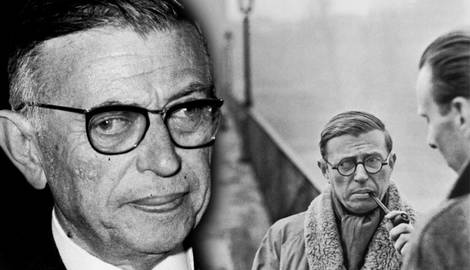

Jean-Paul Sartre was a leading existentialist philosopher. His works examined concepts such as the nature of existence, radical freedom, and the inherent challenges of human relationships. Sartre was an atheist who argued that because God does not exist, people are responsible for giving meaning to their lives. A political activist and Marxist, Sartre sought to bridge existentialism and Marxism. His impact on philosophy as we know it today remains as strong as ever, with many thinkers using his works in their quest for meaning.

Who Was Jean-Paul Sartre?

| Timeline of Key Events in Sartre’s Life | |

|---|---|

| Year | Event |

| 1905 | Born in Paris, France. |

| 1933–34 | Studies in Germany; influenced by Husserl and Heidegger. |

| 1938 | Publishes Nausea, his first novel. |

| 1943 | Publishes Being and Nothingness, his magnum opus. |

| 1964 | Awarded Nobel Prize in Literature (refused it). |

| 1980 | Dies in Paris; ~50,000 people attend his funeral. |

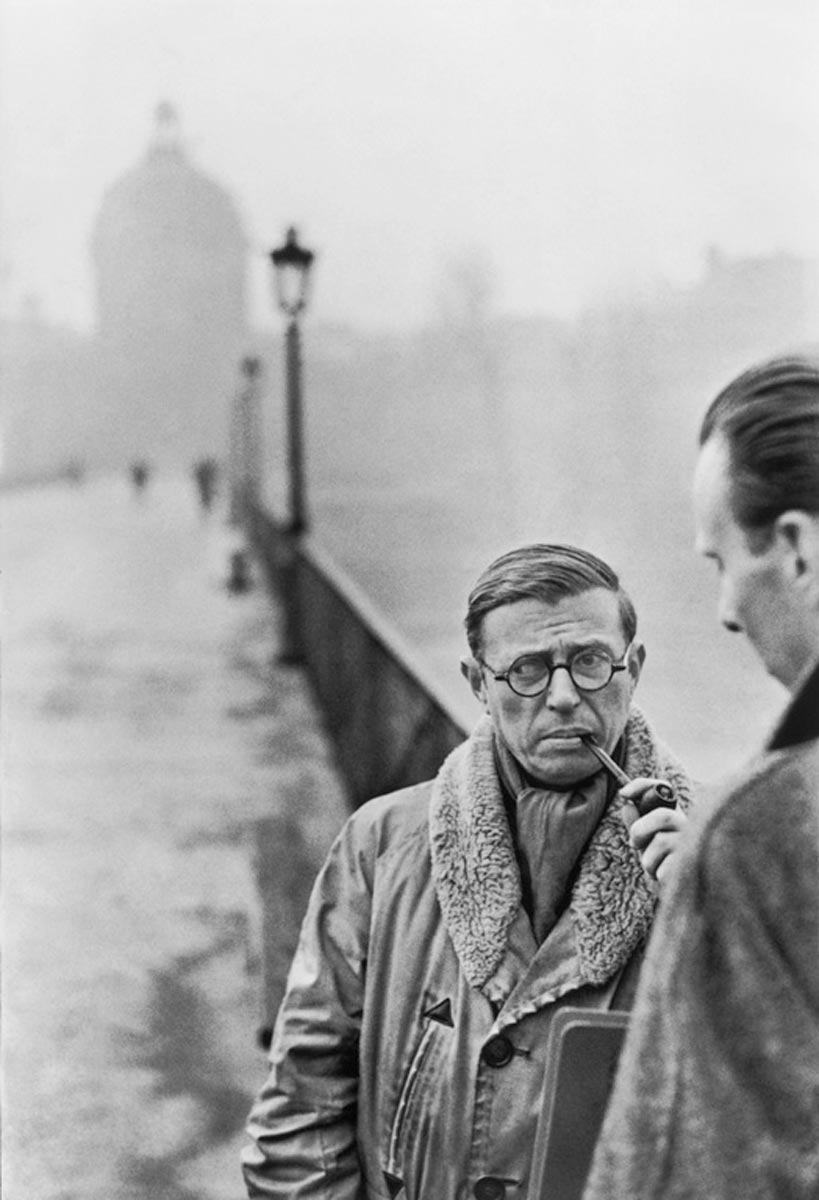

Jean-Paul Sartre was born in Paris in 1905. As an adult, Sartre was known for hosting long philosophical conversations that began with coffee in the morning and dragged on late into the evening over dinner and drinks. But Sartre was not always so sociable. He once described his childhood as “suffocating” and remembered having very few friends. Upon his father’s death, his mother and grandfather raised him. Sartre commented that during this time, he grew up alone with only his books for company. He went on to study at the prestigious École Normale Supériore in Paris and taught philosophy in advanced high schools. From 1933 to 1934, Sartre studied in Germany, where he was significantly influenced by the phenomenological philosophy of Edmund Husserl and Martin Heidegger.

The first book Sartre published was a philosophical novel entitled Nausea (1938). It became a best-seller and immediately solidified his popularity. He published his magnum opus, Being and Nothingness, in 1943 and eventually received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1964. Sartre refused the honor, stating that he did not want to become “a tool of the establishment,” because “a writer should not be an institution.” This incident highlights Sartre’s controversial tendencies, which sometimes got him into trouble and affected his relationships, such as his friendship with fellow existentialist-leaning philosopher Albert Camus.

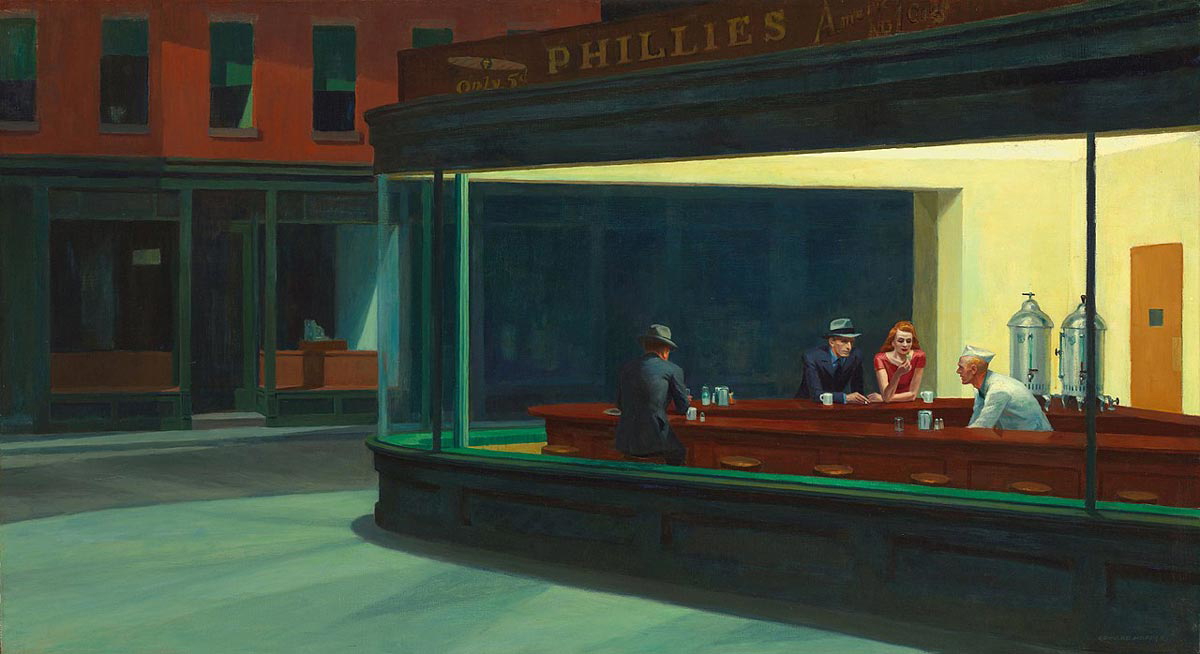

Jean-Paul Sartre lived a very unconventional existence for his time, refusing to follow the common traditions such as marriage or even monogamous relationships, for that matter. However, he did have important human connections, such as with the existentialist philosopher Simone de Beauvoir, which started as a romantic relationship but became a deep friendship. Sartre lived most of his adult life in hotel rooms and did not have many possessions. He spent his days contemplating, discussing, and writing in the cafés of Paris — his two favorites, the Café de Flore and the Café des Deux Magots, were located on the Left Bank of the Seine river.

This alternative lifestyle was consistent with his existential phenomenology and its emphasis on individualism and radical human freedom. Sartre argued that we are always free to choose, which many of his followers found incredibly liberating. By the time of his death in 1980, he had become so renowned that his funeral was attended by around 50,000 people.

What Did Sartre Say About Reality?

Key Takeaways

- Reality is divided into for-itself (consciousness) and in-itself (objects).

- The gap between them, “nothingness,” makes freedom possible.

- We cannot fully know others’ consciousness, which fuels conflict.

Sartre defines reality as fundamentally comprising two parts — subjects and objects. He refers to the former as the “for-itself,” or human consciousness. The latter he refers to as the “in-itself.” While objects are fixed, human consciousness is not — the for-itself is absolutely free. Our consciousness shows us there is a world of possibilities for the for-itself, and thus a gap is introduced between objects, which are fixed, and consciousness, which is possibility. That gap is “nothingness,” as in there is no-thing there.

| View of Reality | |

|---|---|

| Concept | Explanation |

| For-itself | Human consciousness: free, open to possibilities, not fixed. |

| In-itself | Objects; fixed, unchanging, without freedom. |

| Nothingness | The gap between fixed objects and free consciousness — the space of possibility. |

Sartre does not explore how those two realities came about, partly because of his atheism, which is central to his position of radical human freedom. However, the next important implication to explore here is how it connects to his views on human existence. When we look at other people, we assume they have a for-itself, because having consciousness is integral to human existence. However, we cannot enter the consciousness of another human being, so we can only ever assume that others have a for-itself. We only see other individuals as objects.

This situation creates two problems. First, there is the problem that only another subject can recognize another subject, yet we cannot fully confirm the subjectivity of another, thereby undermining our own positions as subjects. Second, it creates an ever-present problem of interpersonal conflict, since we cannot avoid objectifying others.

What Did Sartre Say About Human Existence?

Key Takeaways

- Existence precedes essence: people define themselves through choices.

- We are “condemned to freedom,” responsible for every decision.

- Denying freedom leads to “bad faith” and an inauthentic life.

One of the defining elements of Jean-Paul Sartre’s philosophy is the idea that “existence precedes essence” — this statement expresses his position on human existence and its radical freedom. We are not born with any fixed essence. The choices we freely make in life subsequently shape our essence, which we can make to be whatever we want. Because Sartre does not believe in God, he also believes that nothing is pre-defined. He declared:

“Man is nothing else but which he makes of himself.”

However, Sartre also proclaimed that we are “condemned to freedom.” Our consciousness always reminds us that there is a future open to us and that there are possibilities to freely choose from. Thus, there is a part of our self that is a “not-yet,” which also means that who we currently are is not our full self. As he summarizes it: “I-am-what-I-am-not and I-am-not-what-I-am.” The denial of this kind of human existence is precisely what Sartre argues leads to one living an inauthentic life.

Philosophical inquiry about what it means to “live authentically” is a hallmark of most thinkers who call themselves existentialist philosophers. When we deny our freedom to shape our essences, then we are living in “bad faith,” as Sartre called it. He argued that living authentically should be our primary goal.

What Did Sartre Say About Human Relationships?

Key Takeaways

- Sartre’s famous line: “Hell is other people.”

- We objectify others yet need them to affirm our own existence.

Other people are an additional challenge to living authentically. Sartre famously declared that:

We cannot get inside the consciousness of another being, so we can only assume that others have a “for-itself.” However, only another for-itself can confirm that I too have a for-itself, so we are perennially in this conundrum of not being very sure of much other than the absurdity of human existence and our relationships with others. We think we have the agency to determine what others mean to us, but we also have to assume that others can do the same to us. We need others to understand ourselves, yet we want to believe we have the individual agency to understand ourselves. Therefore, our relationships with others are distorted and alienated. In some ways, we also only have ourselves to blame — a paradoxical and problematic existence indeed.

What Did Sartre Say About Religion?

Key Takeaways

- Sartre’s atheism made humans responsible for creating meaning.

- Believed God’s existence would undermine freedom.

- Ethical choices have no universal guide — each person must decide.

As noted, Sartre’s position on radical freedom is based on his atheism. Since we live in a world without a God, it is up to us to navigate our existence. It is our responsibility to make choices and to give meaning to things. This is seen in how our “for-itself” makes us aware of the gap between fixed objects and future possibilities. His hope is that one ultimately sees more of the optimism in this — we are each completely free to write our own autobiographies as we see fit.

Sartre argued that if God existed then we would not be free. He also argued that the concept of God is contradictory because the standard Judeo-Christian view holds that God is an absolutely, fully realized being. Yet this implies an “in-itself” in Sartre’s terms, and God cannot be both a fixed entity and have future plans at the same time.

This position also suggests that there are no values in the world, which is especially problematic for ethics, given the human desire to assume that there is some kind of moral standard we can use to judge others. Sartre raises this problem in the famous example of the young man who comes to him for advice about either joining the war effort or staying home to care for his aging mother. Sartre tells the man that he has no advice for him. There is no moral theory that Sartre can use to help him; the man must simply decide.

What Did Sartre Say About Politics?

Key Takeaways

- Lifelong activist, positioned on the far left.

- Tried to merge existentialism with Marxism but faced contradictions.

- Criticized capitalism for alienating individuals and masking freedom.

Naturally, Sartre’s atheism is problematic for many. The same can be said for his politics. Sartre was a life-long activist who believed he was never active enough. He resided on the far left of the political spectrum. One of his goals in philosophy was to try to reconcile existentialism and Marxism.

This would prove to be challenging. The Marxist position argues that history is moving in a specific direction that will end in a classless society. This deterministic position conflicts with Sartre’s position on radical freedom. Sartre attempted to work around this problem by arguing that it is not deterministic but rather Marxism is simply the best expression for its time. However, this was not accepted by many people as a successful resolution. Sartre argued that capitalism alienates the individual and turns freedom into an illusion — it masks true reality. But, he argued, we can also find a shared subjectivity as a collectively exploited group, moving from an “us-as-object” role to a “we-as-subject” role. However, this conflicted with his emphasis on individualism as a key feature of existential phenomenology.

Regardless of where one stands on Sartre’s views, we cannot deny his impact on philosophy. He addressed concerns over the pessimism brought on by two world wars and a Great Depression, highlighting the importance of pondering questions of direct human concern. Moreover, his work did not just impact philosophy. Sartre also influenced psychology, art, literature, and theology. His work remains an important revolt against attempts to dehumanize human existence.