The Ten Commandments are the foundation of ethical conduct for Christians, even though they were given to Moses at Sinai. How have Christians distinguished between this moral law and other types of law? Is the origin of the moral law in God or some other source? In what different ways have theologians ordered the Ten Commandments and classified their different uses? Did Christ and the early church reinterpret them? How do different denominations view the law in relation to grace?

The Ten Commandments and Other Laws

The Ten Commandments are a summary of the moral laws contained in the Bible. Moral laws are standards for human behavior and right action that are higher than national laws or personal codes of conduct. Moral laws transcend human laws, containing principles that have a universal and changeless quality. The Ten Commandments encapsulate those moral laws that were given to Moses on Mount Sinai after the escape from Egypt (Exodus chapter 20) and were repeated in the “Second Law” of Deuteronomy (chapter 5).

It is important to understand that there are other types of law in the Old Testament than moral laws. The two most prominent are ceremonial and civil laws. Ceremonial laws center around the worship practices of ancient Israel, containing directions about priests, sacrifices, and festivals. They also include dietary and clothing laws that define what it means to be ritually clean. The civil laws set out what constituted criminal acts and punishments in ancient Israel. They cover issues like contracts, injuries, and inheritance.

There are two other law types that need mentioning in order to understand the moral law outlined in the Ten Commandments. Natural law is a more philosophical approach that places moral principles within human nature and conscience. While the Bible doesn’t use this exact phrase, it does talk about the law of God as displayed in the natural order and written on the human heart. Canon laws are the regulations made by churches for their own government. Christians would argue that both of these should not contradict moral law and in fact, express the same principles.

The Origins of Moral Law

The origin of moral law lies in God’s nature. That means for Jews and Christians the Ten Commandments are a revelation of who and what God is. They do not flow from the will of God and were not created by the choice of God (“divine command theory”). They are a reflection of the moral attributes of God, such as justice, holiness, goodness, and truth. The principles of God’s moral law are eternal and unchangeable like God himself.

There are interesting implications for the divine origin of moral law. One is that God can’t break his own laws. They limit God, or, at least, describe the boundaries of God’s own moral behavior. For example, lying is prohibited in the ninth commandment, so the Bible says that God himself cannot lie. Another is that morality does not exist independently of God, as a code outside God that he is bound to obey (“moral theological objectivism”). Rather, it is an expression of God’s own moral character toward himself and others.

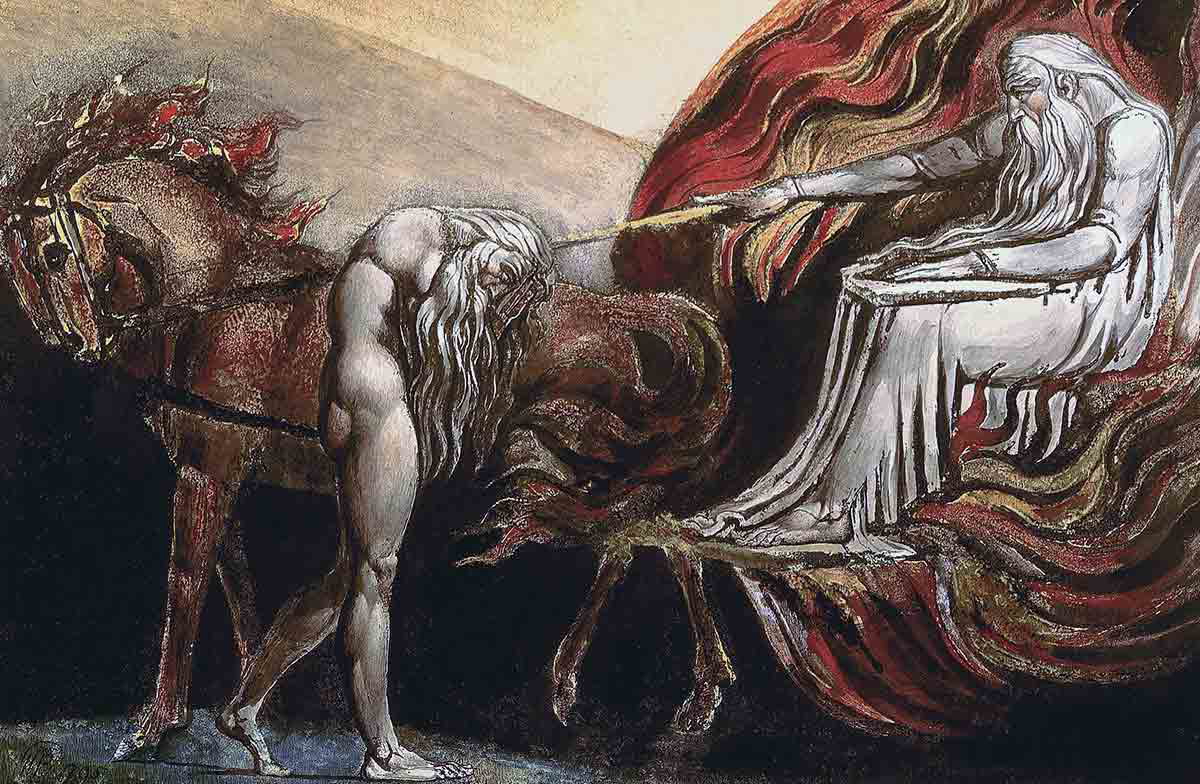

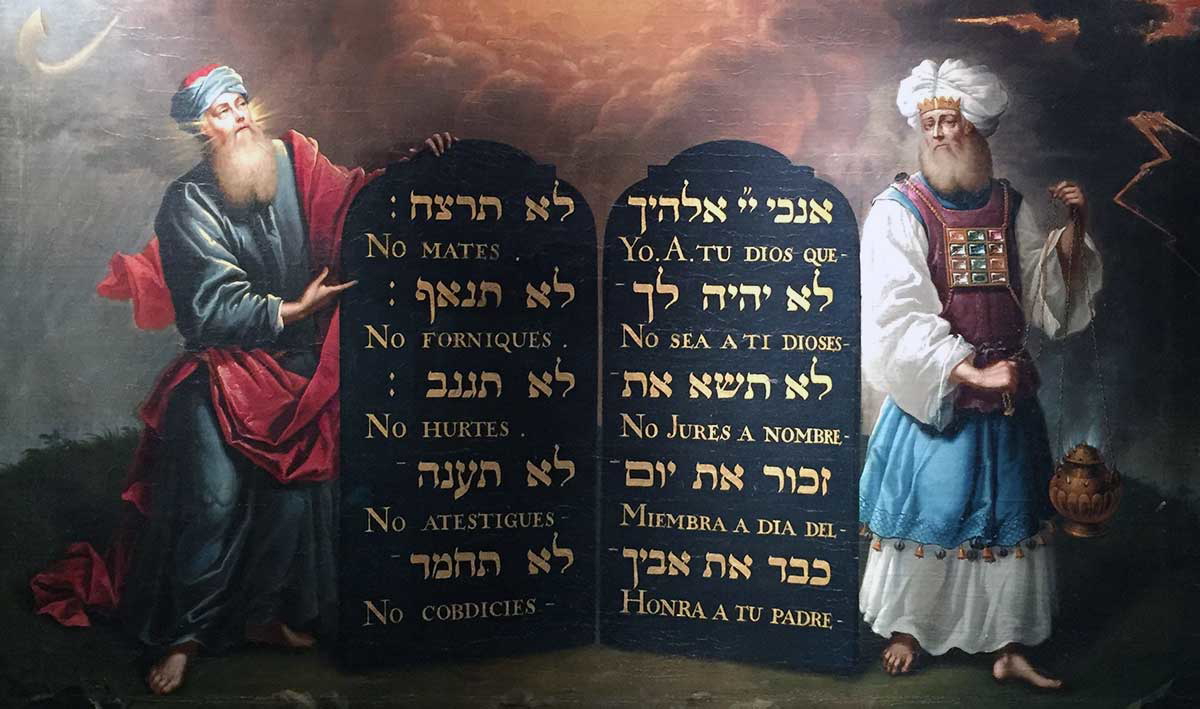

The Ordering of the Ten Commandments

The Ten Commandments were originally written on two tables of stone by “the finger of God” and given to Moses. Theologians usually divide the commandments into two categories, depending on which of the two stones they were written on.

- The first table contained four human duties towards God — (1) don’t worship other gods, (2) don’t make images, (3) don’t take God’s name in vain, and (4) keep the Sabbath holy.

- The second table contained six human duties toward other humans — (5) honor your parents, (6) don’t kill, (7) don’t commit adultery, (8) don’t steal, (9) don’t bear false witness, and (10) don’t covet.

There are some different ways to number and order the Ten Commandments within Jewish, Catholic, and Protestant traditions. The differences come from factors like counting the preface to the Ten Commandments—“I am the Lord your God who brought you out of Egypt”—as the first commandment. Also, the Roman Catholic church combines the first two commandments and then divides the final commandment against coveting into two separate commandments.

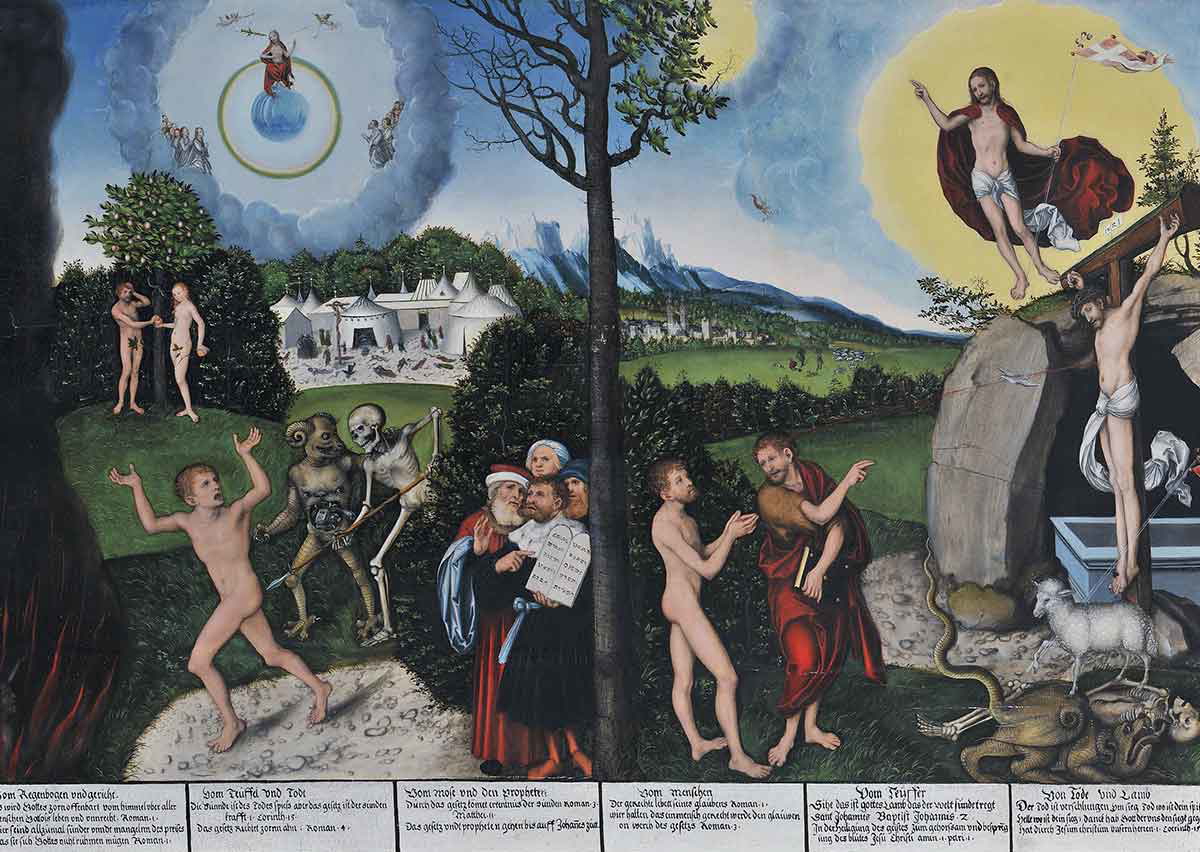

The Three Uses of the Law

Protestants within the Lutheran and Calvinist traditions have generally agreed that the Ten Commandments can serve three purposes in New Testament times. These purposes are commonly known as the “three uses of the law.” They are designed to summarize how the Ten Commandments can function in different settings and for individuals at various points in their religious journey. Sometimes the names and order of these three uses are different, depending on the creed containing them or the theologian discussing them.

The three uses of the law are these:

- The first use of the law is to restrain the external outbreak of sinful actions by individuals in societies through fear of punishment.

- The second use is to reflect the moral perfections and requirements of God when compared to the shortcomings and sins of the human heart.

- The third use is to help Christians regulate their lives in a way that is pleasing to God.

Lutherans call these three uses of the law: curb, mirror, and guide. Calvinists call them (in order) the political or civil use, the elenctic or pedagogical use, and the didactic or normative use. The first two apply to all humans, but the third is only for Christians.

Christ’s Interpretation of the Commandments

Just as Moses received the Ten Commandments on Mount Sinai, Jesus gave his interpretation of the moral law in his famous Sermon on the Mount, along with what we now call the Lord’s Prayer. Here, in the fifth chapter of the Gospel of Matthew, Jesus made it clear that it was not his mission to destroy (demolish, abolish, or abrogate) the Old Testament but to fulfill (complete and accomplish) it. Jesus applies this to both the Old Testament legal and prophetic writings, even in their most minute details (verses 17-18).

Jesus quoted directly from three of the Ten Commandments in his sermon. These are the commandments against murder (the sixth commandment), adultery (the seventh commandment), and lying (the ninth commandment). In each case, Jesus made it clear that not only was he refusing to repeal the commandments, but he was in fact insisting on a higher level of “righteousness” than the external and conditional requirements of the religious leaders of his day. For example, lustful looks constitute adultery, and unjustified anger is nothing less than murder, according to Jesus.

The Council of Jerusalem

Some of the earliest church debates and divisions recorded in the Book of Acts flow from the place of the law for Gentile Christians. Most church leaders, including all the apostles, were Jews, as were the vast majority of the earliest Christians. However, they didn’t have their own nation during the Roman Period. So, the Jewish civil laws were of no consequence. However, the ceremonial laws were still vital to 1st-century Jews, especially laws regarding circumcision and diet.

After claims by some that conversion to Judaism was necessary for Gentile salvation, the church leaders met in what is now called the Council of Jerusalem. This is recorded in Acts chapter fifteen and is also known as the Apostolic Council. There, after hearing from Paul and Barnabas about their work among the Gentiles, leaders including James the Just made the decision that circumcision and adherence to the details of the law were not necessary for becoming a Christian. Instead, it was enough for Gentiles to avoid offerings to idols, sexual immorality, strangled meat, and eating blood (verses 20, 29). The common theme with these prohibitions seems to have been their connection to pagan worship rituals.

Debates About the Moral Law

The debate at the Council of Jerusalem was over a mix of moral and ceremonial law. There has been less debate about the place of the moral law exclusively for Christians. All ten of the Ten Commandments from the Old Testament are explicitly repeated and confirmed as binding in the New Testament. The only potential issue is with the fourth commandment—keeping the Sabbath Day holy—since Christians changed it from the last to the first day of the week and renamed it the Lord’s Day.

Pauline letters like the Epistle to the Galatians have provided Christians with a map for navigating the relationship between law and gospel. However, there have been some movements within Protestantism in particular that have questioned the place of the moral law in the lives of Christians.

- Antinomianism is the belief that the Reformation doctrines of salvation by grace and justification by faith imply freedom from the moral law. This belief tended to be held by extreme sects in Protestantism—often called Anabaptists or the Radical Reformation—who rejected adherence to creeds and confessions.

- Dispensationalism is an interpretive system common to many American fundamentalist churches that stresses discontinuity between Old Testament Israel and the Christian Church. It holds that Christians are under the Law of Christ rather than the moral law of Moses.

It seems only fair to mention that most of the Christian adherents to these two and other similar theological systems still behave according to the principles of the moral law. Their rejection of the Ten Commandments for New Testament Christians is theological rather than practical. They do not believe they are under an obligation to obey the law or the Old Testament as a rule of practice since they are under grace. But their day-to-day living expresses the same moral code.