Bathing is synonymous with the Romans in a similar fashion to roads, legionaries, and togas. The Romans relished the simple enjoyment of warm clean water, a luxury compared to much of the ancient world. Some emperors had luxurious bath complexes named after them called thermae. The historian Suetonius even notes that the best time to ask emperor Vespasian for favors was immediately after his bath.

Stereotypical Roman baths had several rooms on a central axis, which were likely passed through in the following order:

- Apodyterium: A changing room with niches for clothes where bathers would prepare.

- Laconicum and Sudatoria: Dry and wet sauna style rooms.

- Destrictorium: A room where visitors were oiled before entering the rooms of varying temperatures below.

- Caldarium: A hot room with high humidity and a plunge bath.

- Tepidarium: A medium heat room with a luke-warm bath for transitioning between hot and cold rooms.

- Frigidarium: A cold room, often with a large pool.

- Palaestra: A light exercise area.

Roman baths were used by both rich and poor citizens alike and were spread throughout the empire. By the 4th century AD, there were around 850 baths in Rome alone. Here is the story of their origin, rise, and decline.

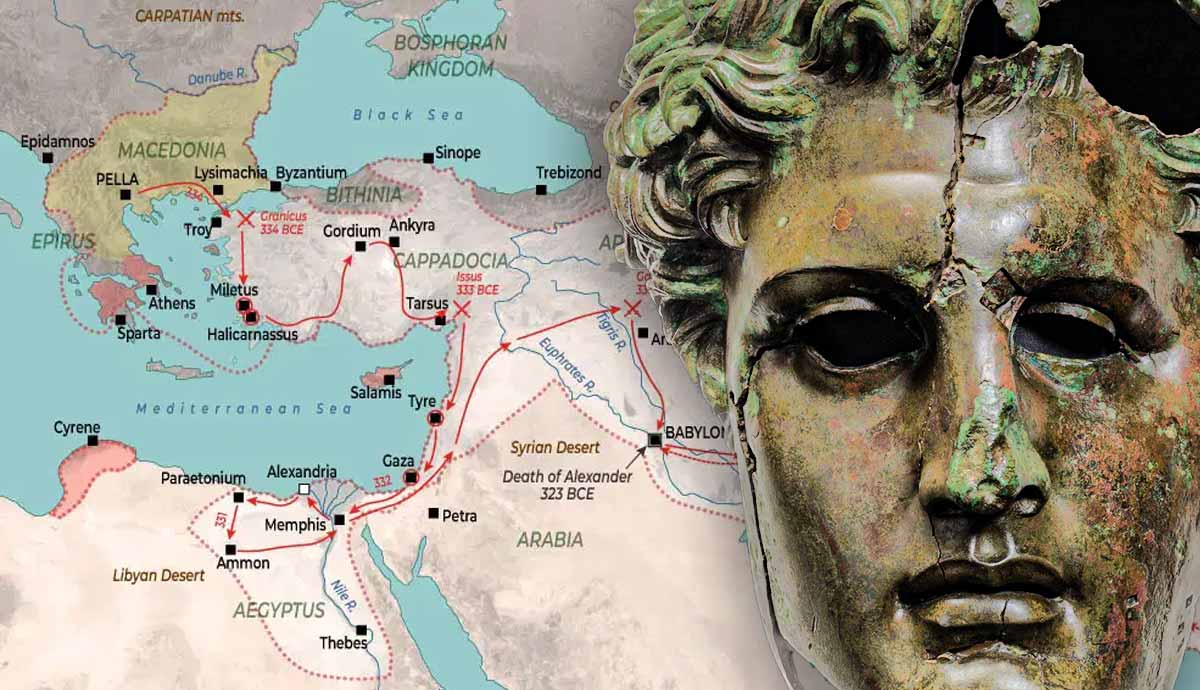

Early Origins Of Roman Baths

Literary and archaeological evidence suggests the roots of the Roman bath began in the Italian peninsula in the 2nd century BC, from two entirely separate traditions. One group of early Roman baths could be found in the gymnasia present in Greek colonies of Magna Graecia and Sicily. On the Greek mainland, gymnasia had long been centers for outdoor exercise, and some contained supplementary baths for athletes to swim and cool themselves. In the Italian-based gymnasia, however, bathing began to grow in importance. This can be seen at Gela, Sicily, where a number of individual baths were added at the center of the bathing complex. By the 1st century BC, the gymnasia in Campania had a large bath complex, suggesting bathing had become as important as exercise.

The second bathing tradition in Italy were the native Italian ‘farm-baths’, or lavatrina. These private farms used bathing for medicinal reasons, and scholars have noted several early elements of later Roman baths can be seen in their design. The buildings featured a changing room (apodyterium), a sweat room (laconicum), a moderately heated room (tepidarium), and a cold water washing area (frigidarium).

Development And Spread Of Public Baths

The last two centuries of the 1 millennium BC saw the emergence of public baths in Italian centers. These buildings combined the Greek traditions of communal exercise and public washing with the Roman ideas of private medicinal bathing complexes seen in the lavatrina. The Stabian Baths at Pompeii are a remarkable early example. The baths have a clear apodyterium, tepidarium, and caldarium for bathing. Outside these rooms was a palaestra for exercise, and a large swimming pool was eventually added. The so-called Pompeiian bath type eventually spread throughout Italy and into the western part of the Roman empire. Previously separated male and female areas were frequently removed, and emphasis was placed on ensuring aesthetic views from the Caldarium’s windows.

Early Roman baths particularly showcase the development of the advanced Roman hypocaust heating system. The baths at Fregellae even featured wall-based heating utilizing a network of terracotta tubes and studded tiles.

As baths grew in popularity, they rapidly spread throughout urban centers and occupied street blocks much like other civic buildings. In these locations, they were as accessible to local inhabitants as shops and soon became ingrained in civilians’ daily routines. The baths offered the enjoyment of clean, warm water, often not easily available, as well as the opportunity to escape busy street life for a while.

Baths In The Provinces

Just as Roman religious deities combined or mixed with local provincial gods, bathing traditions outside Italy combined Roman ideas with local preferences and ideas.

In North Africa, the Roman baths kept the Italian central axis of temperature-controlled rooms. However, the frigidarium grew in importance due to the hot climate and was frequently flanked by a set of pools. A further consequence of the hot weather was the changing function of the palstrae. The open space was predominantly used as a social area, rather than for athletics.

The Hunting Baths at Lepcis Magna are excellently preserved North African baths, which were discovered buried in the sand. The complex has an unusually octagonal design consisting of an identical set of hot water bathing areas branching out from a central frigidarium. Most significantly, the internal walls of the Hunting Baths are decorated with a variety of frescoes and mosaics depicting hunting scenes. The imagery likely follows Homeric themes and suggests the owners or users of the complex were responsible for sourcing and capturing the exotic and aggressive wildlife of the area.

In the eastern portion of the Roman Empire, bathing had been heavily associated with the Greek gymnasia. These sites predated Roman baths by several centuries and many remained in use, placing a greater emphasis on athletics than bathing. Although new bath complexes were inevitably constructed, in many cases bathing areas in existing gymnasia were simply expanded to meet the Roman-influenced demand. The Harbour Bath Gymnasium at Ephesus, for example, originated as a gymnasium, but the bathing room added to its western axis. The frigidarium, however, contained a central swimming pool large enough to allow athletics to take place within. This dual-function was frequently seen elsewhere in the eastern provinces, and sites normally incorporated areas suitable for storing equipment and oiling athletes.

Roman bath complexes within military bases also had to cater for exercise to ensure the fitness of their occupants. The example at the fort at Isca features a large palaestra and a swimming pool with an attached circuit.

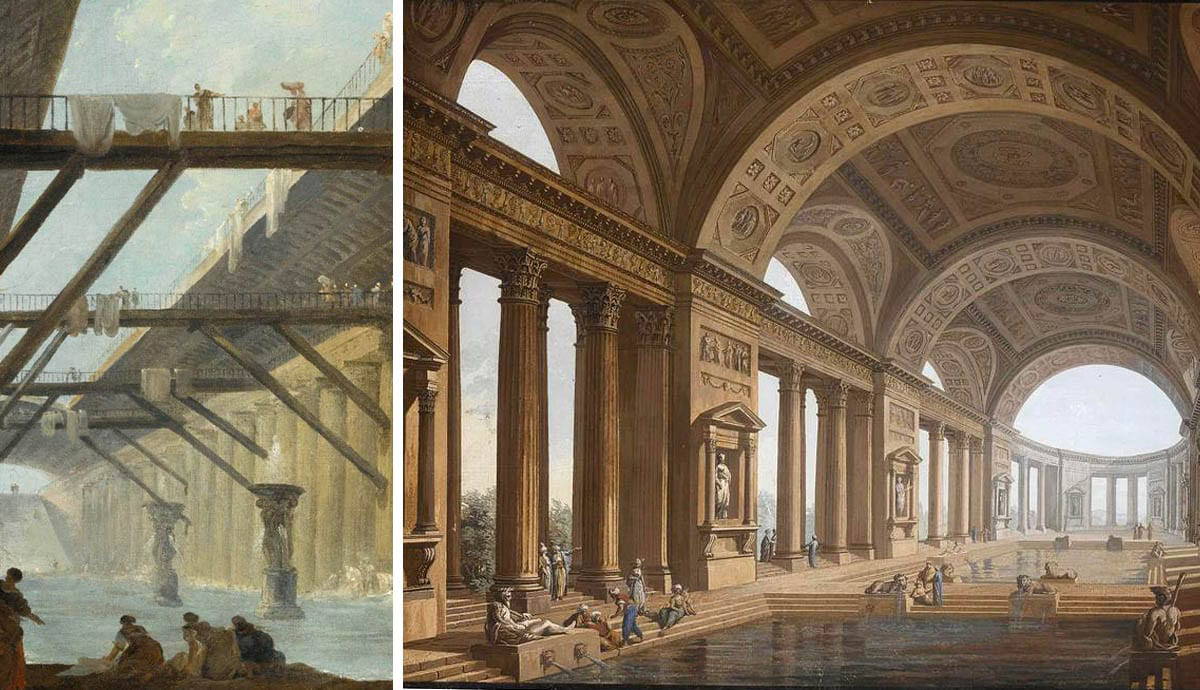

Roman Thermae

Roman baths and bathing culture reached their epoch in the magnificent and elaborate thermae. These luxurious bathing complexes dominated the surrounding landscape and were often named after the ruling emperor. Many thermae displayed trophies and sculpture throughout and acted as visible statements of Roman power to any who entered. Thermae were often the largest buildings for miles around and therefore served numerous secondary functions. It was not uncommon for lecture halls, libraries, and even shrines and gardens to be attached to the central bathing complex.

The Thermae of Caracalla in Rome is perhaps the best-preserved example of one of these magnificent buildings. Many of its walls still stand too near their original height – giving a sense of the sheer scale and grandeur of the complex in antiquity. The Thermae of Caracalla was constructed close to Rome and used a large-scale earth-moving operation to create level ground from a nearby hill. The complex was orientated around a large central domed caldarium decorated with hunting scenes. The enormous amount of bathers were catered to by extensive bread making facilities. A complex washing operation was also necessary to ensure a constant supply of dry towels were available.

Caracalla’s thermae would be the unofficial economic and civic center of the local province. Shops and offices were present throughout, and lecture theatres were available for teaching. The site also likely formed the base for athletes who could utilize the extensive gymnastics facilities.

Roman Baths In Late Antiquity

The decline and eventual collapse of the Western Roman Empire resulted in an inevitable breakdown of the infrastructure needed to keep bathhouses operational. In the surviving Eastern Empire, baths had always enjoyed less popularity and were now expensive and difficult to keep open. Despite this, Roman baths began to take on important roles and civic centers and continued to be constructed, although in smaller, simpler styles. The main change saw the frigidarium enlarged and transformed into a multi-purpose, bathing, and relaxation area.

The baths at Serjilla, Syria, were built in the late 5th century. The traditional long axis of rooms was instead replaced by a domestic style layout dominated by a large hall and bathing lounge. Hot bathing areas were predominantly represented by a series of individual small rooms designed for travelers.

In contrast to the continuing public importance of baths, the Byzantine thermae of Zeuxippus served a new ceremonial purpose. The site’s use was restricted to the emperor himself and was used for ritual bathing several times a year, and public displays such as preaching.