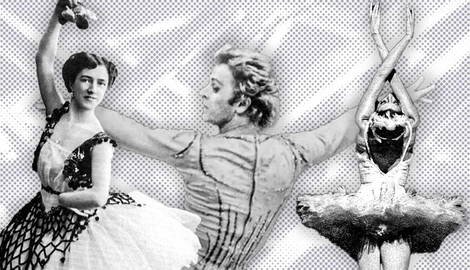

A ballet performance is a high art form that can awe audiences. However, audiences only see the result, not the blood, sweat, and tears it takes to become a dancer at a premier ballet company like the Bolshoi Ballet. In the Soviet Union, dancers at the top of their game had access to power, luxury apartments, and foreign travel. The KGB also shadowed them. Famous Russian ballerinas developed techniques like the Vaganova Method or broke boundaries for minority women. Other dancers risked everything to escape and pursue their art. Read on to discover 9 famous and influential ballerinas from Russia and the USSR.

1. Aleksandr Gorsky (1871-1924)

Aleksandr Alekseevich Gorsky almost did not join the ballet. Headed for a career in commerce, he was discovered by accident when he visited the Petersburg Theatre School with his sister in 1879. After studying with famous teachers Platon Karsavin and Marius Pepita, Gorsky joined the Imperial Ballet Company. Within a decade, he debuted his first work, Clorinda.

From 1902 to 1924, Gorsky acted as the Bolshoi Ballet’s creative director, developing new ballet versions of Swan Lake, The Little Humpbacked Horse, The Nutcracker, and Salome’s Dance.

Gorsky, a talented choreographer who influenced ballet realism, brought Konstantin Stanislavski’s method acting to ballet. At the time, the corps de ballet often sat or stood on the stage during performances. Gorsky changed the troupe from static to expressive and active. He also infused classical ballet with folk dance elements that transformed the genre.

After the Soviets seized power, ballet’s existence became precarious due to its aristocratic association. The art form survived by evolving into new experimental forms representing Soviet values. Gorsky, who struggled with mental health, died in a Soviet asylum in 1924.

2. Agrippina Vaganova (1879-1951)

Agrippina Vaganova was not a natural ballerina. Instead, she had to work extra hard to become a star. Born to an Armenian and Russian family, she joined the Mariinsky Theater (later known as the Kirov State Theater) as a teenager. First, she joined the corps de ballet and later became a solo dancer. By 1915, her role as the Goddess Niriti in The Talisman won her the title of prima ballerina.

Known for her tremendous flights with long pauses in mid-air, Vaganova became known as the “queen of variations.” She revived Pepita’s and Gorsky’s variations on The Little Humpbacked Horse, Esmerelda, Giselle, Don Quixote, and Swan Lake.

Vaganova became a choreographer, professor, and artistic consultant for the Bolshoi. Just before the Russian Revolution, she quit the stage to focus on teaching.

During the 1940s and early 1950s, Vaganova worked as a professor at the Leningrad Choreographic School. Her precise techniques, now known as the Vaganova Method and published in Fundamentals of Classical Dance, became a fundamental ballet textbook.

Vaganova received multiple awards during her lifetime, including a People’s Artist award and the Stalin Prize. Her teaching methods, enshrined in classical ballet technique, are still taught today.

3. Vera Karalli (1889-1972)

Born in Moscow, Vera Karelli inherited a love of the stage from her parents. Her big break came when Aleksandr Gorsky invited her to join the Bolshoi. Within two years, Karelli debuted a solo role in Swan Lake to thunderous applause. By 1915, she became a full Bolshoi ballerina.

Known as Gorsky’s favorite dancer, Karalli also became one of the first Russian silent film stars. Her renditions of Chrysanthemums, Retribution, and The Dying Swan made film history.

As the mistress of Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich, Karelli was one of two women allegedly present at the Yusapov palace the night of Russian peasant healer Grigori Rasputin’s murder in 1916. In the aftermath, Karelli fell into disfavor with Empress Alexandra and left Russia. When revolution broke out, she chose not to return.

In exile, Karelli danced with the Ballets Russes and taught ballet. By World War II, she had her own Paris studio. As she aged, Karelli longed to return to her homeland and petitioned the Soviet government to allow her to live in Russia. Two weeks before she died in 1972, the Soviets finally issued the stateless dancer a Russian passport. Sadly, she never got a chance to use it.

4. Tamara Khanum (1906-1991)

Born into an Armenian family in modern-day Uzbekistan, Tamara Artyomovna Petrosyan (later Tamara Khanum) was a singer, dancer, actress, and choreographer.

Tamara grew up in a world where Armenians inhabited an ethnic borderland that reflected the conflicted history of Russian colonization in the Caucasus and on the frontiers of Central Asia. Tamara grew up in a radical atmosphere. During the 1920s, the Soviets initiated an anti-child marriage, anti-polygamy, and anti-religious campaign. They also banned the paranja (the Uzbek equivalent of the burqa). As a result, the streets of Tashkent and Samarkand erupted in violent confrontations between Uzbeks and Soviets, who had been sent to tear the veils from women’s faces. Tamara soon joined this revolutionary scene.

As a teenager, Tamara began dancing with a group headed by Uzbek writer and human rights activist Hamza Niyazi. In 1922, she enrolled in the Tashkent Ballet Company and later graduated from the Central Technical School of Theater Arts in Moscow.

During the 1920s and 1930s, Khanum toured with Uzbek ballet groups and ethnic ensembles. She starred in roles such as Halima and Farhad and Shirin, which featured less visible minority voices.

Back home in the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic, Khanum played a crucial role in developing the Uzbek National Ballet Theater, the State Uzbek Opera, and a ballet school. During her lifetime, Khanum performed over 600 songs in multiple languages and infused her works with traditional Uzbek dance moves. In 1925, Tamara became one of the first to display Uzbek art at the 1925 World Exhibition of Decorative Arts in Paris. A decade later, she participated in the First World Festival of Folk Dance in London.

Tamara did not just dance. From 1937 to 1948, she worked for the Supreme Soviet of the Uzbek SSR. Along the way, Khanum also bucked several Islamic traditions.

She fought for women’s rights in Uzbekistan. She collected folk dance styles from diverse cultures, such as Jewish, Bashkir, Crimean Tatar, Ossetian, and Uighur, and helped develop them into the first Uzbek ballets. Creative and fearless, Tamera encouraged girls in the audience who came to talk to her after a show to work, study, and make their own marriage decisions.

When some men overheard Khanum, they told her, “This is not accepted here.”

Tamara refused to accept defeat. “It will be,” she exclaimed. “It will be accepted here, in Uzbekistan.”

Tamara’s fight to empower women and develop ethnic ballet in her homeland succeeded. But activism came with a price.

One of Tamara’s troupe members, Nurkhon Yuldashkhojayeva, became an early Uzbek actress. On March 18, 1928, Nurkhon and another teenage dancer, Tursunoy Saidazimova, had made a sensation when they danced onstage without their paranjas.

When Nurkhon returned home to visit her family that summer, her brother, Salixo’ja, was waiting for her with a knife. Her murder, planned by her father and the mullah Kamal G’iasov, who had Salixo’ja swear on the Qur’an to murder his sister, ignited public outrage. At her funeral, women tore off their veils and threw them in front of her casket.

On May 10, 1928, 17-year-old Tursunoy Saidazimova also died at her husband’s hands in an honor killing for performing without a veil. At her funeral, the crowd cried as Tamara Khanum’s teacher, Hamza Niyazi, a poet, playwright, and activist, read a eulogy for the teenage dancer.

In 1929, Tamara Khanum received tragic news about her beloved teacher. A People’s Writer of the Uzbek SSR and founder of Uzbek social realism, Niyazi went from village to village, teaching women to read, discouraging violence against women, and supporting women’s emancipation. Supporting the Soviet policy of hujum and his own passion for social justice, Niyazi organized a rally in Shakhimardan on International Women’s Day. He told women that, according to Soviet law, they no longer needed to wear veils. In response, 23 women took off their paranjas in public and threw them on the ground.

On March 18, 1929, a group of men from the village of Shakhimardan attacked Niyazi and stoned him to death. After his death, some revered Niyazi as a human rights activist, while others saw his efforts as anti-Uzbek and anti-Muslim. These Uzbek women’s voices are still remembered today, thanks largely to Hamza Niyazi’s poems.

During World War II, Khanum toured the front lines to entertain the Red Army with over 1,000 performances. Khanum and her Uzbek troupe also performed at the Bolshoi Ballet in Moscow, Leningrad, and Kyiv, as well as in Iran, Turkey, India, Mongolia, and Europe. In 1941, she received the Stalin Prize and the People’s Artist of the USSR award in 1956.

Today, Tamara Khanum is known as the honorary mother of Uzbek dance.

5. Galina Ulanova (1910-1998)

Born into an artistic St. Petersburg family, Galina Ulanova grew up in the traditions of the Mariinsky Theater. Her fluid technique, expressiveness, and ability to fade a movement into thin air made her a Soviet star.

Soldiers, politicians, and authors raved about her performances. The Soviet writer A. N. Tolstoy called Ulanova “an ordinary goddess,” while Boris Pasternak, the author of Dr. Zhivago, cried during her performances.

They weren’t her only fans. After seeing Ulanova’s performance, Joseph Stalin transferred her to the Bolshoi. For 16 years, she reigned as prima ballerina assoluta. In 1951, she won the title of “People’s Artist of the USSR.”

When the Bolshoi Ballet gave its first Western performance in 1956 at the Royal Opera House in London, Ulanova’s performance cemented her reputation as one of the best ballerinas of the twentieth century.

6. Olga Lepeshinskaya (1916-2008)

Born in Kyiv, Ukraine, to a noble Polish family, Olga Lepeshinskaya took a straightforward path to Soviet success. She graduated from the Bolshoi Ballet School in 1933, three years before Stalin’s Great Purge.

By 1939, Lepeshinskaya had gained notice as Svetlana in the eponymous patriotic ballet. In this role, she played a heroine who thwarted anti-Soviet saboteurs who seemed to exist everywhere. Another of Lepeshinskaya’s famous ballet roles, Red Poppy, outraged visiting Chinese communists such as Mao Zedong and caused an international uproar. But the show went on. In 1953, Lepeshinskaya even danced the Red Poppy with a broken leg fractured in four places. The Soviets later edited the ballet to better reflect Chinese culture.

In 1943, Lepeshinskaya joined the Communist Party. She danced for the Red Army during World War II and married twice, both times to generals in the Soviet State Security Services (NKVD, then later the KGB). Her first husband, Leonid Reichman, headed the NKVD’s Polish office. Reichman oversaw the coverup of the Katyn Forest massacre of 5,000 Polish officers (with a mass killing of almost 22,000 Polish citizens) in 1940 after the partition of Poland between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union.

When the NKVD arrested Reichman in 1951 for his role in the fabricated Zionist Plot, Lepeshinskaya did not let her husband’s fall from favor derail her career. She divorced him. They later remarried, but when the KGB arrested the general again after Stalin’s death, the ballerina divorced him a second time.

Thanks to her skill and top-tier connections, Lepeshinskaya gained status as Stalin’s favorite ballerina. She won the Stalin Prize three times and became a People’s Artist of the USSR. Lepeshinskaya’s persona made her the epitome of a Soviet ballerina whose dynamic style and versatility matched her commitment to Soviet ideals and earned her a lasting reputation in the ballet world.

7. Maya Plisetskaya (1925-2015)

Born in Moscow to a Jewish family from Lithuania, Maya Plisetskaya’s early years were marked by tragedy. The Soviets kicked her father out of the Communist Party and arrested him during the Great Purge, and her mother disappeared into the gulag for several years. Despite her family history, Plisetskaya joined the Bolshoi during World War II. She became a dancer, director, choreographer, and actress.

Her modern technique and enormous jumps dazzled audiences in the Soviet Union. But the KGB kept her from performing in the West for 16 years due to “political immaturity.” In 1951, despite protests from the Komsomol, she won the title of Honored Artist of the USSR.

Yekaterina Furtseva, the steely Soviet Minister of Culture known as “Catherine the Third,” banned Plisetskaya’s “un-Soviet” performance of Carmen when it premiered at the Bolshoi Ballet in 1967. Furtseva, who once famously mixed up an opera and a symphony, a mistake quickly observed by critics, denounced all ballet as “erotica.” She would turn up at performances wearing jewels and an astrakhan fur coat to denounce even faint criticisms of Soviet policies as anti-state behavior. Plisetskaya, once called the “world’s best dancer” by Nikita Khrushchev, won in the end. The Bolshoi Ballet’s version of Carmen, popularized by Plisetskaya, became a legend.

After Galina Ulanova retired in 1960, Plisetskaya became prima ballerina assoluta at the Bolshoi. She danced into her eighties, winning three Lenin prizes and a medal for state service.

8. Mikhail Baryshnikov (1948- )

Born in Riga, Latvia, Mikhail Baryshnikov made waves for his technical skills as a dancer at the Kirov Ballet. In May 1974, he joined the Bolshoi Ballet as a guest star for an international trip.

In the post-Stalin era, dancers still faced political restrictions on art. Baryshnikov wanted to transition to modern choreography, an evolution impossible at home.

On the night of June 29, 1974, Baryshnikov defected while on tour in Toronto, Canada. After the show, Baryshnikov acted fast. While he signed autographs, his Canadian friends waited to pick him up in a car a few blocks away. He later described his act as an artistic choice rather than a political statement. Baryshnikov defected at the right time. Ballet was hot in America, thanks to the “dance boom” during the 1970s.

Baryshnikov soon joined the American Ballet Theater. Then, in 1978, he joined the New York City Ballet. That same year, Kirov dancer Aleksandr Godunov defected during the Bolshoi’s New York City tour. As an artistic director, Baryshnikov participated in award-winning films and television specials like White Nights and Dancers.

In 1990, Baryshnikov co-founded the White Oak Project to pursue projects reflecting his passion for modern dance. During his career, Baryshnikov collaborated with other famous artists such as Martha Graham, Rudolph Nureyev, and Margot Fonteyn. Baryshnikov became a celebrated choreographer, director, and teacher who fused classical ballet with pioneering choreographies. His consummate technique and willingness to experiment influenced modern American dance.

9. Alexei Ratmansky (1968- )

Born to a Ukrainian-Jewish father and a Russian mother, Alexei Ratmansky enrolled in the Moscow State Academy of Choreography at age 10 in 1978.

When the Soviet Union dissolved in 1991, Ratmansky expanded his international repertoire. He developed acclaimed versions of classical ballets. His original creations such as Firebird, On the Dnieper, and Seasons draw inspiration from ancient Greece and Jewish folklore. His reputation as a choreographer for the Bolshoi, Royal Danish Ballet, and the Paris Opera Ballet grew.

During his career, Ratmansky worked at the American Ballet Theater, the New York City Ballet, and as the Bolshoi Ballet’s artistic director. His ballets have won numerous awards, including a Bessie Award, the Golden Mask Award, and the British National Dance Award.

Art, Protest, and Resilience

For over 100 years, these dancers evolved as artists, creating pioneering works and techniques like the Vaganova Method that are still taught today. Some famous Russian ballerinas confronted racial barriers and fought for minority women’s rights. Other dissident dancers protested political restrictions or chose to pursue art outside their homeland.

This phenomenon did not stop with the Cold War.

When news broke about Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Olga Smirnova, the Bolshoi’s prima ballerina, left the country, while Alexei Ratmansky walked out of a Bolshoi performance to protest the war. Ratmansky went on to create Wartime Elegy, which debuted at the Pacific Northwest Ballet in Seattle and is dedicated to the people of Ukraine.