In the mid-14th century, Catherine of Siena became one of the most influential holy women in the Roman Catholic Church, gaining an extensive following due to her asceticism and charitable work. Born when the papacy underwent considerable challenges, Catherine of Siena was also active in the political landscape, calling for religious reforms and lobbying for support for Pope Urban VI among the European elite. After her early death, Catherine of Siena’s mysticism and faith continued to influence believers through her doctrinal treaty and extensive collection of letters. Here are 9 facts about this Catholic saint:

1. Catherine of Siena Had 24 Siblings (and She Was a Twin)

Born Caterina di Benincasa on March 25, 1347, Catherine of Siena was either the 23rd, 24th, or 25th (historical accounts vary) child of Jacopo di Benincasa, a dyer, and Lapa Piagenti, the daughter of a Sienese poet. Most of her siblings, however, tragically did not survive to adulthood. In the years immediately following her birth, the outbreak of a pandemic known as the Black Death (probably caused by Yersinia pestis, the bacterium causing plague) ravaged Tuscany, the Italian region where Siena is located, causing widespread death, especially in the densely populated towns.

Catherine’s twin sister, named Giovanna, died shortly after being given to a wet nurse, a common practice at the time. When Catherine was two years old, her parents had another daughter.

According to her confessor and biographer, Raymond of Capua (Raimondo delle Vigne), the Master General of the Dominican Order beatified in 1899, Catherine was a happy child whose cheerful attitude earned her the nickname Euphrosyne, meaning “joy” or “satisfaction.”

In his Life of Saint Catherine of Siena, Raymond reports the young Catherine, already deeply religious, had her first vision of Jesus Christ when she was around six years old. According to Raymond, Catherine saw Christ surrounded by the Apostles Peter, Paul, and John while walking home with one of her brothers after paying a visit to a married sister, Bonaventura. The vision inspired Catherine to pursue a religious life.

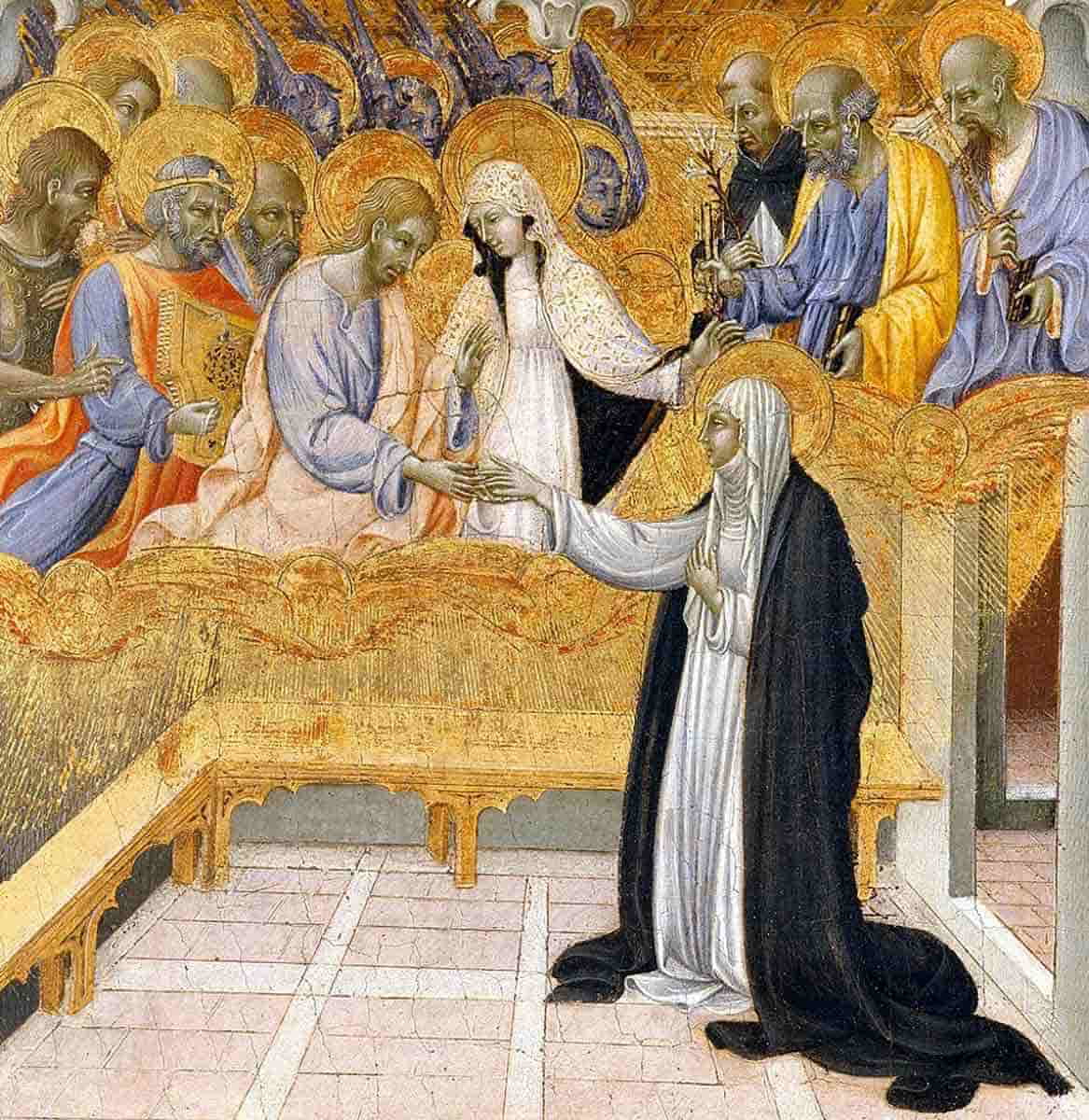

2. She Experienced a Mystical Marriage With Jesus

While Catherine vowed to dedicate her life to Jesus, her mother still hoped to persuade her daughter to find a husband and marry. Young Catherine initially yielded to Lapa’s pressure to take more care of her appearance, however, she later made her intention to remain a virgin clear by cutting her hair. Her father then allowed her to use a room in the family house to pray and meditate.

In the following years, Catherine spent most of her time in isolation in her room, praying and fasting. Then, around 1368, she experienced a mystical marriage with Jesus Christ. According to her biographer’s account, around the Carnival season, Jesus appeared to Catherine while she was praying in her room and said to the young woman, “Because thou have shunned the vanities of the world and forbidden pleasure, and have fixed on me alone all the desires of thy heart, I intend, while thy family are rejoicing in profane feasts and festivals, to celebrate the wedding which is to unite me to thy soul. I am going, according to my promise to espouse thee in Faith.”

In a letter to Sister Bartolomea Della Seta, Catherine herself recounted her mystical wedding, remarking, “Well seest thou that thou art a bride, and that He has wedded thee and every creature, not with a ring of silver, but with the ring of His Flesh.” The wedding ring was only visible to Catherine.

Known as “spiritual espousals,” the mystical marriages appear in several lives of the Catholic saints. Indeed, in the Old and New Testaments, the link between God and his chosen people is often described as a relationship between a bride and a groom. Celebrated in a ceremony attended by Mary, various saints, and angels, the marriages symbolize a deeper connection with Jesus Christ and his sufferings and inspire the chosen person to become more charitable.

After her vision, Catherine of Siena became more active in her community, tending to the sick in the Hospital of Santa Maria della Scala.

3. She Received the Stigmata

In 1375, Catherine of Siena experienced another pivotal religious ecstasy. According to Raymond of Capua, Catherine confided to him that, during a stay in Pisa to persuade the town’s government not to join the anti-papal league, she saw “my crucified Saviour who descended upon me with a great light; the effort of my soul to go forth to meet its Creator, forced my body to arise. Then from the five openings of the sacred wounds of our Lord, I saw directed upon me bloody rays which struck my hands, my feet and my heart.”

Visible only to herself, Catherine of Siena’s stigmata was officially recognized as valid by Pope Urban VIII in 1623. In Christian mysticism, the stigmata refers to the wound marks corresponding to those inflicted on Jesus Christ by the crucifixion. Often received during religious ecstasies, these alleged miraculous marks may be temporary or permanent and symbolize a special union with Jesus Christ’s suffering. Saint Francis of Assisi was famously the first one to allegedly receive the stigmata.

Today, the wooden crucifix from which Saint Catherine received the stigmata is located in the Church of the Crucifix, a Baroque-style place of worship built in the Shrine of the House of Saint Catherine in Siena.

4. Catherine of Siena Was an Ascetic

Throughout her life, Catherine of Siena followed a rigid asceticism. In particular, she was used to fasting frequently to achieve a more complete spiritual union with Jesus Christ. “Knowing as I do that no other food can please or satisfy the soul, I am saying we must walk along the way, and he is the way. What was his food? It was what he ate along this way: pain, disgrace, torment, abuse, and in the end the shameful death of the cross. So we must eat this same food,” she declared in a 1376 letter to Frate Niccolò da Montalcino.

Originating from the Greek askeō, meaning “to exercise” or “training,” asceticism originally referred to abstaining from various pleasures to achieve an ideal level of bodily fitness. In many religions, including Christianity, the term asceticism is linked to the belief that living a simpler life, devoid of physical or psychological desires, preserves a person’s spirituality.

5. She Was a Political Activist

As her following grew, Catherine of Siena began to play an active role in the Papal States’ affairs. In 1309, Pope Clement V moved the papal capital from Rome to Avignon, a town in southeastern France, inaugurating the period known as the Avignon Papacy.

In 1376, Catherine of Siena visited Pope Gregory XI in Avignon, where she sought to negotiate peace in the conflict known as the War of the Eight Saints between the pope and an anti-papal league headed by Florence and lobby for a crusade. While her calls for peace and a crusade did not bear the results she hoped for, Catherine of Siena was more successful in urging Gregory XI to return to Rome, believing that restoring the former papal capital may put an end to the hostilities in the Italian peninsula. Gregory XI finally agreed to leave Avignon the following year.

However, the end of the Avignon Papacy did not benefit the papacy, nor did it bring peace across the peninsula. Following the election of the Bishop of Bari as Pope Urban VI, a group of cardinals in Agnani elected a rival pope (Clement VIII), who, after failing to challenge Urban VI’s legitimacy, relocated to Avignon. It was the beginning of the so-called Great Western Schism, a period when several antipopes vied for power with disastrous results for the papacy’s prestige and political stability in Italy.

During these turbulent years, Catherine of Siena traveled across Tuscany to persuade various local governments not to join anti-papal leagues while urging Urban VI to unite the Catholic Church.

6. She Was Not a Nun

While Catherine of Siena led a deeply religious life, she never became a nun. Instead, she opted to join the Dominican Third Order in Siena, an organization that allowed lay men and women to follow their religious vocation without living in a convent.

In Siena, the tertiaries of the Dominican Order were commonly known as Mantellate (cloaked) after the distinctive cloak they wore above their clothes. As a mantellata, Catherine began gaining widespread attention because of her charity work (especially following her Mystical Marriage) and rigorous lifestyle. Among her growing number of followers were both secular people and members of the clergy.

Around 1370, Catherine began corresponding with several of her disciples, offering advice and encouragement on how to achieve their spiritual goals. Though she had probably already learned to read, she dictated most of her letters.

7. She Died of Starvation

In the last years of her life, Catherine of Siena’s long-term fasting practice led to a decline in her health. Like other ascetics, Catherine saw fasting as a means to cleanse her body and soul from sins and share Jesus Christ’s sufferings. “In our sufferings we will experience eternal life even in this life. Though we are in pain we will not suffer. Rather, suffering will be refreshing for us when we consider that suffering can make us like Christ crucified in his disgrace,” she declared in one of her letters.

The extreme fasting eventually depleted Catherine’s body. She died in Rome on April 29, 1380, at the age of 33. Her body is buried at the Basilica of Santa Maria sopra Minerva in the Italian capital. Her thumb and mummified head, however, are revered as relics in the church of St. Dominic in Siena, her hometown in Tuscany. A relic of her foot is in the Basilica of Saints John and Paul in Venice.

8. She Is One of Only Four Women Named Doctors of the Church

In 1970, Saint Catherine of Siena became one of the 37 Doctors of the Church, a title only three other women received: St. Teresa of Ávila, St. Thérèse of Lisieux, and St. Hildegard of Bingen. To this day, Catherine of Siena is the only laywoman ever named a Doctor of the Catholic Church.

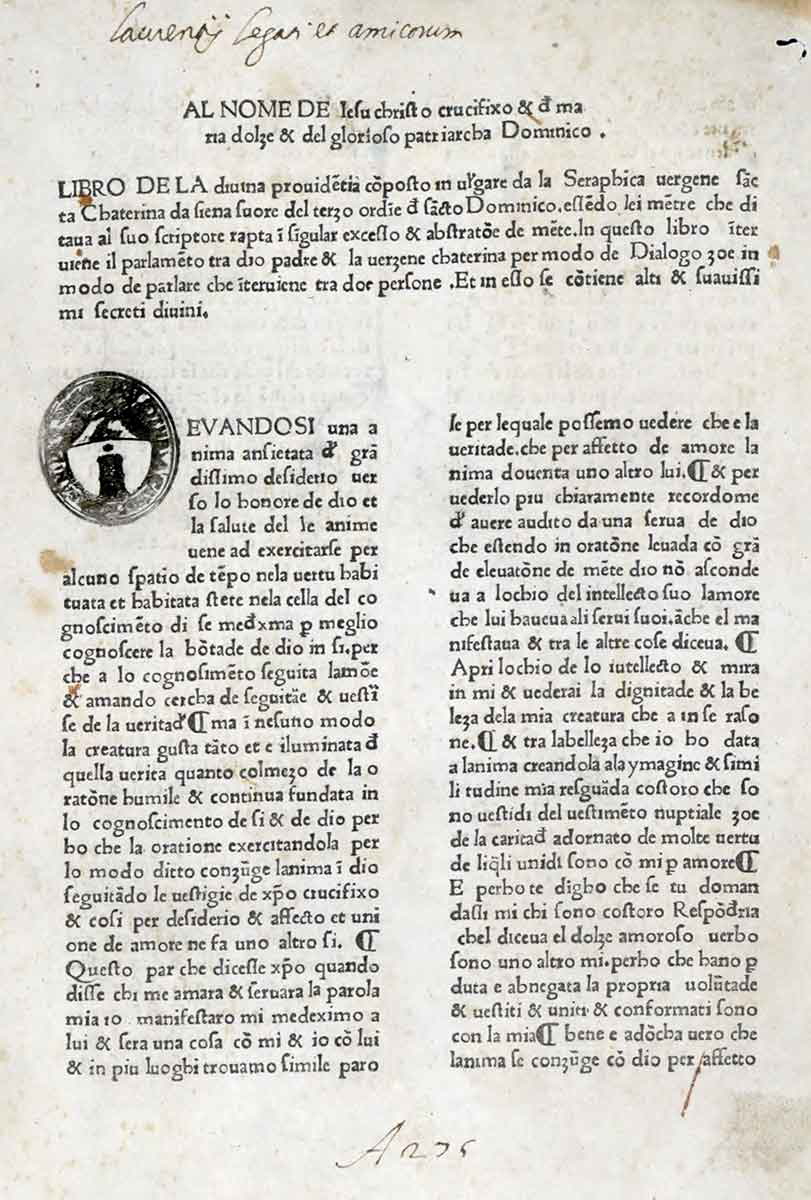

In the Roman Catholic Church’s theological system, the title of Doctor of the Church is given to saints whose writings are thought to be of particular importance in Catholic Catechism. Before her death, Saint Catherine of Siena recorded her theological doctrine in Il libro della divina dottrina (translated into English around 1475 with the title The Dialogue of Divine Providence).

A combination of four treaties (Of Divine Providence, Of Discretion, Of Prayer, Of Obedience), The Dialogue is a detailed record of the saint’s ecstatic experiences and mysticism written in the form of a series of dialogues between God and Catherine of Siena’s soul. In giving readers direction on how to achieve a deeper connection with God, Catherine often refers to Jesus Christ as a “bridge” between God and the souls of the believers. Indeed, her theology revolves around the figure of Jesus Christ, whom Catherine describes as the symbol of divine love.

Influenced by the works of Saint Augustine and Saint Bernard and written in the Tuscan vernacular of the 14th century, The Dialogue would, in turn, influence early Italian literature. Besides her doctrinal treaty, Catherine of Siena left behind 26 prayers and more than 380 letters. Among her correspondents were influential figures of 14th-century Europe, such as the kings of France and Hungary, the queen of Naples, various members of the Visconti family from Milan, and popes Gregory XI and Urban VI.

9. Catherine of Siena Is a Co-Patron of Italy and Europe

Canonized in 1461, Saint Catherine of Siena became chief co-patron of Italy in June 1939, sharing the title with Saint Francis of Assisi. Citing the troubling times Italy and Europe were facing (Nazi Germany would invade Poland in September, starting World War II), Pius XII expressed his hope that the two saints, who lived during “extraordinarily difficult times,” would inspire believers through their virtuous examples.

In particular, Pius XII remarked that Saint Catherine (described as “the most powerful and pious virgin”) played an instrumental role in ending the papacy’s “exile” in Avignon, thus acting for the “honor and defense of the Fatherland and Religion.”

In 1999, John Paul II proclaimed Catherine of Siena the patron saint of Europe, declaring: “By the assurance of her bearing and the ardour of her words, the young woman of Siena entered into the thick of the ecclesiastical and social issues of her time.”