The term “Scholasticism” can be misleading because it generally describes a “method” of philosophy rather than a particular school such as Stoicism or Nihilism. Still, some thinkers are generally categorized under the umbrella term of “Scholastic philosophy.” As a method, Scholasticism is inextricably linked to the rise of the medieval universities. Universities became centers of scholastic study, which focused on logic and the dialectic method of ancient Greek philosophers. Some of the most significant Scholastic philosophers are Anselm of Canterbury, Peter Abelard, Duns Scotus, William of Ockham, and Thomas Aquinas.

The Rise of Scholasticism

While in many ways the Middle Ages seem to be foreign to our times—from drinking urine to ward off the plague to the societal structure of feudalism—there are also important contributions from the period that have remained surprisingly unchanged. Some of these include the judicial process of trial by jury, the governmental institution of constitutional monarchy, and most importantly for our purposes here, the university.

The rise of monotheistic religions intensified philosophical debate over the role of faith and reason in everyday life. During the flourishing of Ancient Greek philosophy, the dominant view was that reason superseded faith, broadly speaking. The rise of Christianity triggered a reversal of this trend. During the Middle Ages, Biblical scripture reigned supreme as the ultimate authority on all matters. However, in the 12th century, important translations of Ancient Greek thinkers such as Aristotle became more prevalent thanks to Arab transcriptions. Attempts to reconcile reason and faith began to emerge and this work became known as the Scholastic method. Most thinkers we now label Scholastic philosophers were pursuing their work in universities—hence the term “Scholasticism,” which refers to the “method of the schools.”

The First Western Universities: The Home of Scholasticism

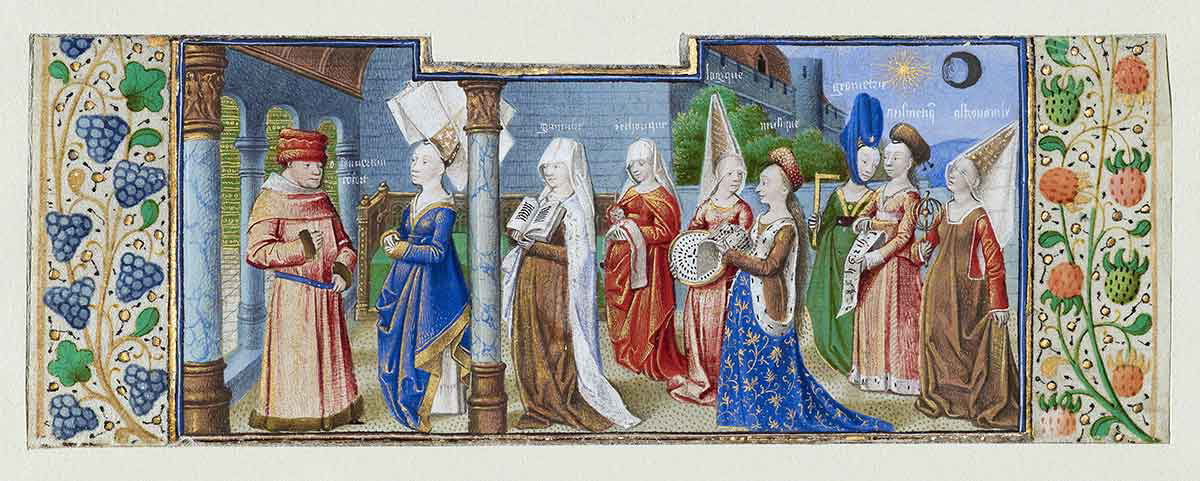

The first universities in the West developed in the late twelfth and early thirteenth centuries and as noted, they were remarkably similar to universities today. However, there were still some very important differences, including the fact that women were not permitted to attend such institutions. There were several key reasons for the increase of universities in Europe. One very influential factor was the rise of the city. The expansion of urban life came about due to many factors, but suffice it to say for our purposes here that this urban shift required a more educated class of people. Growing cities brought new socioeconomic needs and structures, which in turn required new skills to administrate it all. One such new skill was the use of dialectical reasoning to navigate new and old challenges, a practice which lies at the heart of the Scholastic method.

The Method of Scholasticism

As noted, another important connection with the development of the Scholastic method was the new prevalence of Ancient Greek texts, especially Aristotle. Historians of philosophy record Aristotle as the “father of logic”; thus, his logical method became especially dominant among Scholastic thinkers. This method, initially referred to as “dialectics,” originally meant “the art of conversation” where structures and techniques were employed to rationally arrive at logical conclusions. The goal was to solve problems, such as that of the aforementioned reconciliation between faith and reason. Scholasticism became the dominant form of philosophizing in the High Middle Ages. And, while the methodology was generally similar among the Scholastic philosophers, there were of course important differences too.

One of the earliest medieval proponents of the Scholastic method was Peter Abelard (1079-1142). He is perhaps best classified as a moderate Realist who argued that the kind of universals that exist take the form of “mental concepts,” which allow humans to be better critical thinkers. In one of his most important works, Sic et non (For and Against, also translated as Yes and No), Abelard clearly illustrates the Scholastic method at work. He applies the principles of logic and tackles key theological issues by analyzing all sides to work toward a resolution. Admittedly, much of his work comprises meditations rather than concrete answers. However, it is clear that Abelard was dedicated to analyzing all the different points of view on a given subject.

The Via Antiqua Versus the Via Moderna

The scholastic dialogue later entered another rift that is known as the Via Antiqua versus the Via Moderna. The former was considered to be the “old-fashioned way,” and is characterized by views such as those of Thomas Aquinas on the complimentary nature of faith and reason. The latter was considered the “modern way,” and sought instead to completely separate the two. The Via Moderna would eventually prevail, leading into the next historical shift in the history of philosophy, the Modern Period.

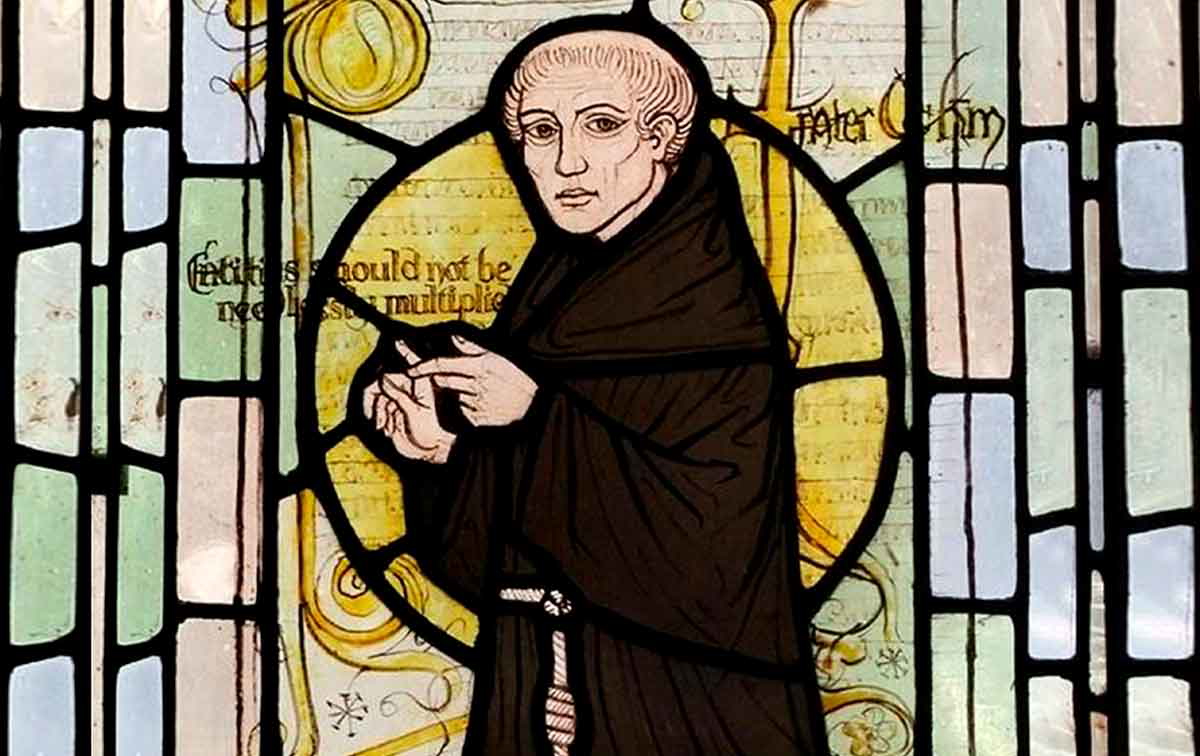

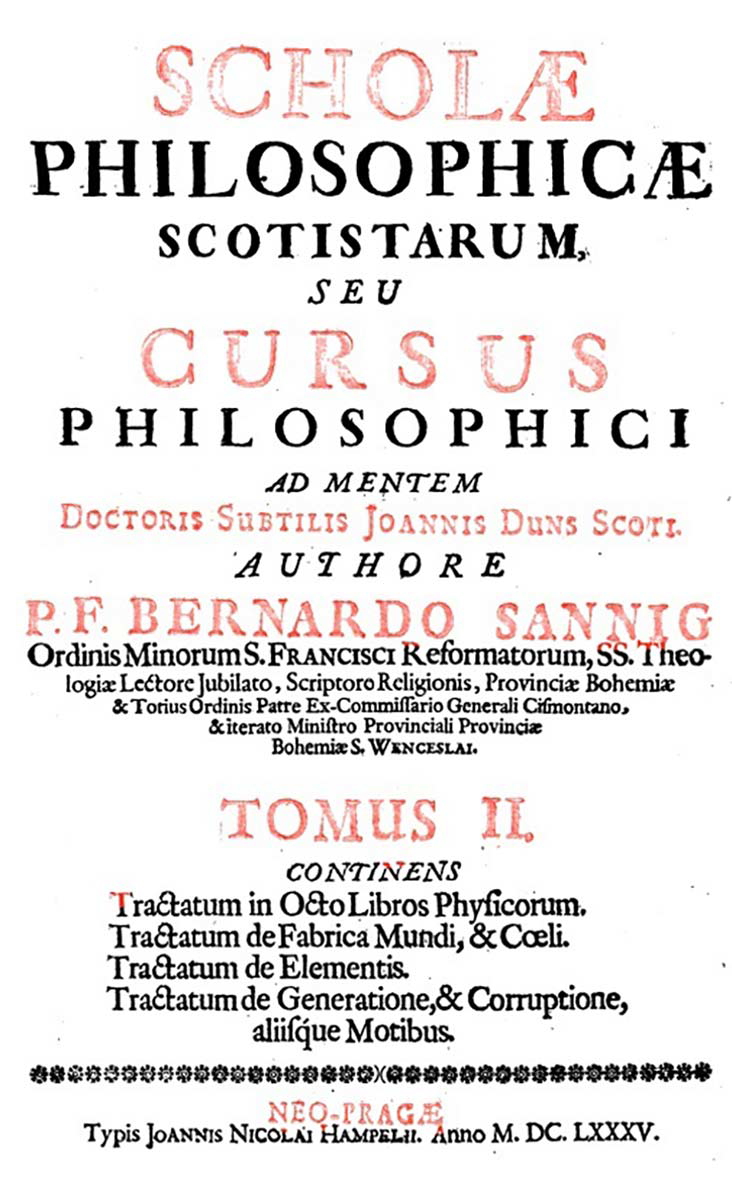

John Duns Scotus (?-1308) and William of Ockham (1287-1347) are good examples of this split. Scotus argued for the ultimate power and authority of God as evidence for the superiority of faith over reason. God’s existence cannot be proven through the use of human senses and reasoning capacities, it can only be based on faith. Ockham agreed that belief in God could only be based on faith, but he did not want to take reason out of the equation and separated the two concepts instead. Faith belongs in the realm of religion, and reason belongs in the physical world. This led him to develop what later became known as “Ockham’s razor,” the position that we should strip away superfluous elements in reasoning about this world and use only relevant data when performing logical analysis. The idea was to get at the core of a problem: when there are competing explanations, choose the simplest one.

Scholastic Philosophers

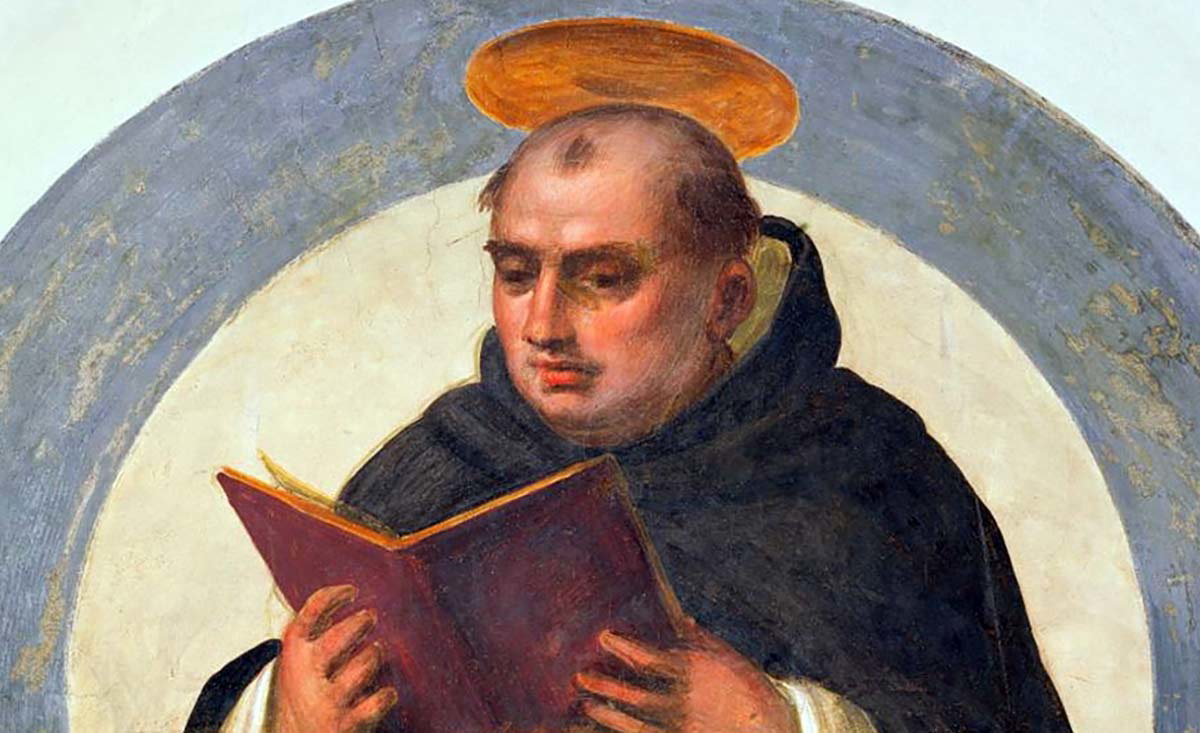

Perhaps the greatest of the Scholastic philosophers was Saint Thomas Aquinas (?-1274), who appeared in the period of the High Middle Ages when Aristotelian studies were well integrated into academic dialogue. Aquinas followed a Scholastic method similar to that of Thomas Abelard. He rationally analyzed theological issues and the debate surrounding them to reach carefully reasoned solutions. Aquinas’ goal was the reconciliation of faith and religion, and most particularly a rational explanation of God’s existence. He would also note cases where only one or the other could provide knowledge i.e. reason versus revelation. But he mainly wanted to show how reason and revelation could work together. One of his most important works, Summa Theologica (1274), was a summary corpus of virtually every key Scholastic issue. He explored 631 questions by presenting opposing views and analyzing where they err, where they conflict, and what we may reason from the dialogue.

Most of the significant Scholastic philosophers come from this later period, the High Middle Ages, and most of them come from religious orders—secular philosophers are rare. From the Dominican Order, we have Saint Thomas Aquinas as well as Saint Albert, and from the Franciscan Order, we have John Duns Scotus, William of Ockham, and Saint Bonaventure. Thus, despite different positions on faith and reason as a source of knowledge, a faith-based life was predominant throughout the medieval period in Europe; faith ultimately usually reigned over reason.

Criticism of the Scholastic Method

This method, however, was not without its critics during its time. As we just saw, there were important fractures among the Scholastic philosophers. Moreover, not so unlike the dissonance between those of the analytic tradition and those of the so-called “continental tradition” today, some thinkers objected that Scholasticism focused too heavily on logic at the expense of basic intuition and even at times the loss of truth in the process. Logical methods can be so impressive, and it was argued that sometimes this became the priority over pursuing knowledge: dazzling audiences took precedence over the pursuit of truth. Dante was one such critic who became concerned that some thinkers used this logical method to impress rather than to reach the truth.

Moreover, by the end of the 14th century, there were several universities of importance. The expansion of institutions of higher education also led to different ways of philosophizing. The rigorous, logical method of Duns Scotus would be challenged by a more mystical, less analytic method of new thinkers such as Meister Eckhardt. Some would try to reconcile Scholastic and mystical ways of philosophizing, as others had done with reason and faith. An important result was the widening of the long, centuries-old conversation that is the history of philosophy. As is so often the case in this perennial dialogue, often the inquiries raised rather than the answers proposed are the most influential step forward.