In the 10th century, a group of nomadic Turks called the Seljuks began a migration through Central Asia, searching for pasture for their herds. By 1071, this tribe had formed a mighty empire that encouraged the Turkic migration and settlement of Anatolia. This would ultimately lead to the establishment of other powerful Turkic dynasties, such as the Ottomans.

Seljuks: Nomads From Central Asia

The Oghuz Turks, the ethnic group to whom the Seljuk Dynasty belonged, originated in Central Asia. They had lived a pastoralist and nomadic life throughout the early Middle Ages. The Oghuz Turks were transhumant, meaning that they followed a pattern of seasonal migrations with their herds of animals. Historians believe that the Oghuz were originally a tribal confederation that, like many others, developed an ethnic identity. There were 24 major Oghuz tribes. The Kinik tribe was considered a prominent one, and a man named Seljuk (late 10th century) was a chieftain belonging to this tribe.

Seljuk and his nomadic followers were accustomed to a tribal life on the volatile open grasslands, or steppes, of Central Asia. From a young age, tribespeople in this region learned how to ride horses like experts. Also, the threat of constant attacks by other tribes made them skilled in the art of war and defense. Archery was a valued art and an effective weapon for horseback riders. This made steppe nomads like the Seljuks (and later the Chinggisid Mongols) a dangerous force to be reckoned with.

Though sources from this period are scarce, it is believed that Seljuk worked as a mercenary or chieftain for the Khazak Khaganate, a Judeo-Turkic polity situated around the Volga River. Possibly due to a falling out with the Khazak rulers in the late 10th century, Seljuk gathered his followers and began a southward migration that would forever change the fate of Asia and Europe.

Entry Into Anatolia

It was Seljuk’s grandsons Tuğril (d.1063) and Çağri who turned Seljuk’s small tribe into an empire. They conquered various cities around Central and Western Asia, including Nishapur (Iran) and Merv (Turkmenistan). However, it was Çağri’s son, Sultan Alp Arslan (d.1072) who began the incursion into Anatolia.

To appease his unruly nomadic followers, the Sultan organized several gaza, or Islamically-sanctified raiding parties, into Christian territories. The Oghuz were accustomed to a tribal steppe lifestyle defined by inter-tribal raids and warfare. Their conversion to Islam did not stop them from their traditional raiding and looting, of which Muslim households were now the target. This upset the citizens of the “civilized” Islamic centers of Baghdad and Tabriz, who expected the Seljuk Dynasty to protect them.

Directing the nomads’ energies towards Christian lands would not only save the reputation of the Seljuks in Islamic lands but it would also gain them territory, power, and prestige.

The Seljuks had already conducted campaigns in Anatolia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan. In 1064, they conquered Ani (Eastern Anatolia), which the Byzantines could not protect. War between these two powers became inevitable as the Seljuks pushed further into Anatolia.

In 1071, on the plain of Manzikert in Eastern Anatolia, the Byzantine army was defeated by Seljuk forces. That same year, the Seljuks secured Jerusalem, leading to the First Crusade (1096-1099).

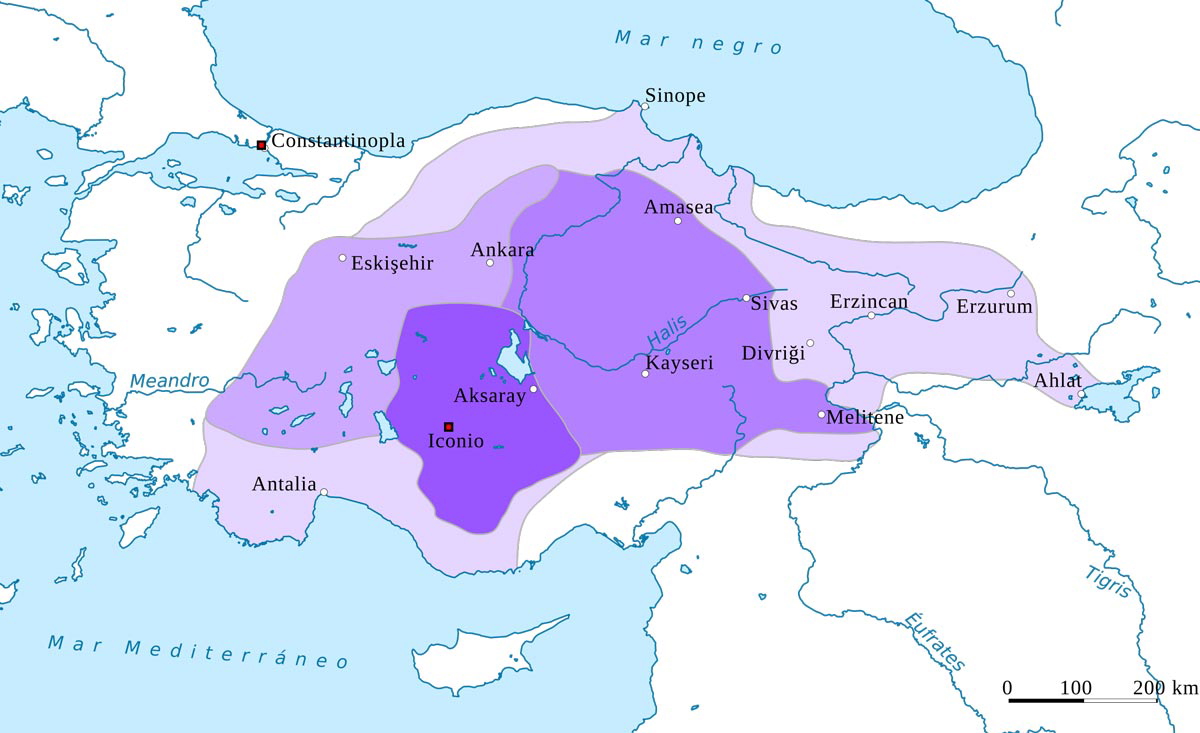

The Sultanate of Rum

The most crucial effect of the Battle of Manzikert was that it opened Anatolia to Turkic settlement. Hordes of Oghuz nomads—now called “Turkmen” to separate them from some Oghuz tribes who were still pagan—migrated to cities like Ani. In Anatolia, they found rich pasture and a terrain very similar to the steppe lands of Central Asia. This was a major factor in their permanent settlement in the country.

Another factor in the Turkic settlement of Anatolia was the weakening of the Great Seljukid Empire based in Iran. By 1090, the state was beginning to show signs of decline. A power struggle between Sultan Malikshah’s wife Terken Hatun and the Persian Grand Vizier Nizam-ul-Mulk ended in the latter’s death and Terken’s removal from power.

After Nizam-ul-Mulk’s death, the empire began to disintegrate. Yet, rather than disappearing altogether, the Seljuk Empire came back to life as the “Sultanate of Rum.” Rum referred to “Rome,” another name for Anatolia. In the early 12th century, Suleyman Shah I, cousin of Sultan Alp Arslan, set up his new capital in Iconium, the modern-day city of Konya.

Court and Social Life in Seljuk Anatolia

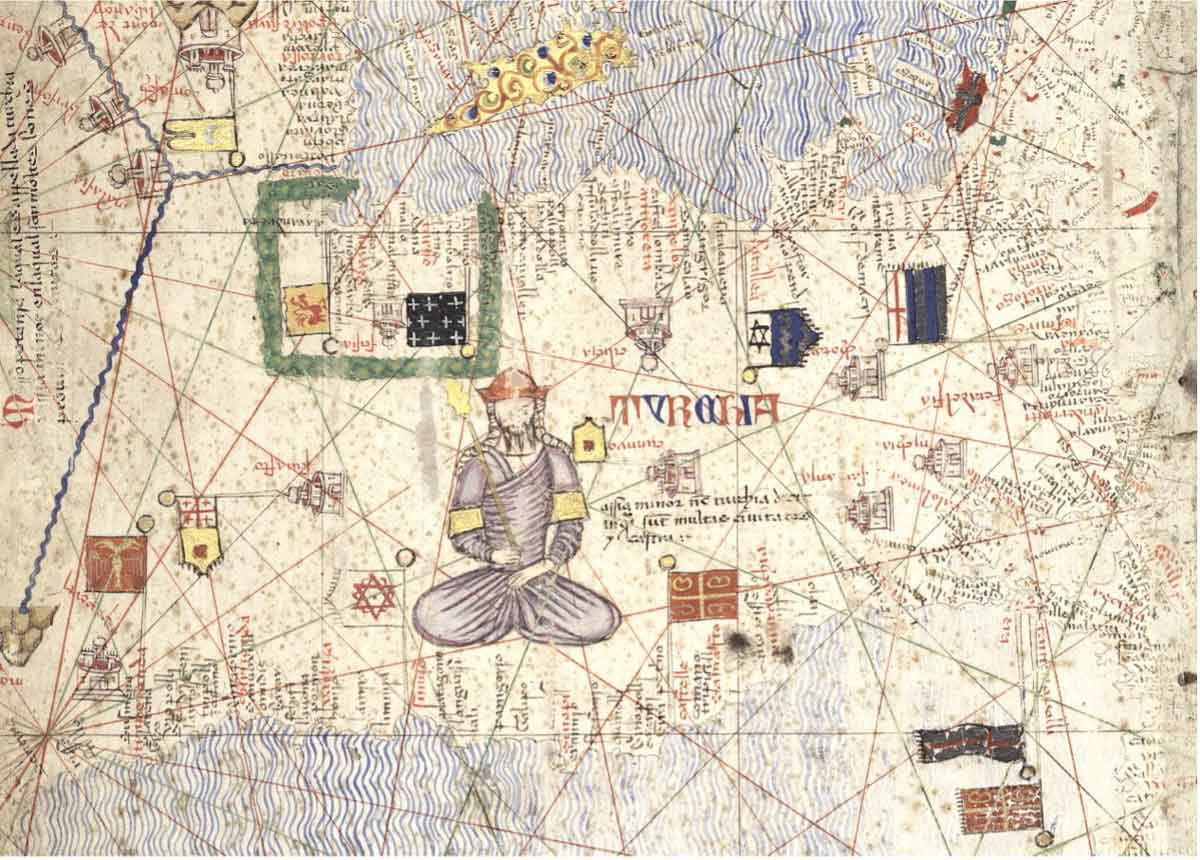

The Seljuks of Anatolia existed in a different political and social milieu than their brothers in Iran and Iraq had. Anatolia had a large Christian population, mainly made up of Greeks (called “Rum,” or Romans), Armenians, and Assyrians. There were also other populations, like Kurds and Arabs in the East. The entry of nomadic Turks had added another ethnic and religious element to this melting pot.

Communities were not only divided along ethnic or religious lines. Sedentary peoples who lived in villages and towns, whether Christian or Muslim, mistrusted and feared nomads. The Turkmen nomads sometimes raided villages to obtain farmed goods that they could not produce themselves. Other times, nomads and townspeople traded goods at markets, facilitating a transfer of cultural and religious ideals.

Amongst the elites and royals, Persian culture and language, rather than Turkic, was more popular. To the Seljuks, Persian language, literature, and religious movements, like Sufism, were considered more refined and superior to the Oghuz culture which was increasingly associated with “uncouth” nomads. Many court officials, along with popular personalities, like the Sufi poet Jalal-al-Din Rumi, were Persian and wrote in the Persian language.

The Seljuks were also great patrons of art, science, and architecture. They built scores of mosques, caravanserais, hospitals, and madrasas (schools of learning) in their cities. In their art, they mixed Turkic and Persian motifs. Unlike other Islamic dynasties of the period, they liked to depict human, animal, and mythological figures in their palaces and pottery.

The Beyliks

Although the diverse communities in Medieval Anatolia played different roles, it was the Turkmen who dominated politics. The Turkmen nomads who had supported the Seljuks since the 10th century, and who made up the bulk of their followers, also held military power. They made up the military class, including soldiers, commanders, and generals who were given timar (land grants) in return for their service.

As Turkoman chiefs proved themselves in war and raids, they were given titles and land by the Seljuks. Backed by their followers, chiefs and “gazis” (raiders), like Danishmend Gazi (d.1085), formed their own principalities. Danishmend was a renowned gazi who formed the Danishmendid principality that eventually rebelled against the Seljuk Sultanate.

These principalities, ruled by “beys,” meaning “lords,” were called beyliks and thus, the period from the late 11th to the 14th century is also often referred to as the First Beylik Period. The lords of these principalities were supported by the Seljuks at times because they secured land for the Turks and weakened the Seljuks’ Byzantine and Crusader enemies.

The Mongol Invasions

By 1220, the Anatolian Seljuks were at the height of their power. Yet, to the east, there was a new force threatening to destroy all in its path: the Chingissid Mongols. Under the command of Chinggis Khan, the Mongol Empire was expanding considerably throughout Central and Western Asia. After this conqueror’s death, the Mongols continued to invade nations across Eurasia, including Anatolia.

These invasions culminated in the Battle of Köse Dağ in 1241. The Mongols were led by Baiju Noyan, an effective commander appointed by Chinggis Khan’s son Ögedei Khan. Located in the mountain ranges of Köse Dağ, between the cities of Sivas and Erzincan, the battle was a decisive factor in the fall of the Anatolian Seljuks. The Mongols defeated the Seljuk army using steppe warfare tactics, like the famous feigned retreat of steppe warriors. Interestingly, these were tactics that the Seljuks themselves had used before their state took on a more sedentary and Persian identity.

Although the Seljuks outnumbered the Mongol army, the latter fought ferociously and had effective commanders, something that the Seljuk forces lacked. The Seljuks were decimated, many of their soldiers eventually deserting the battlefield. As a result, Seljuk Sultan Keyhusrev II fled to Ankara. He eventually accepted Mongol suzerainty, paying an annual tribute to the Mongol Khaganate. This marked the end of independent Seljuk rule in Anatolia and began their slow process of decline.

The Downfall of the Seljuk Dynasty

After the decisive battle of Köse Dağ, the Seljuks reigned largely as figureheads. They were challenged by other Turkmen principalities, like the Karamanids, who disagreed with the Seljuks’ non-aggression policy towards the Mongols. These Turkmen could not accept being under the rule of those they considered pagans and infidels.

In 1277, the Karamanids—who had long interfered in Seljuk politics—annexed Konya, the capital of the Seljuk state. However, since the Seljuks had the Mongol army’s military support, they defeated the Karamanid army.

Still, this did not put an end to popular rebellions against the Seljuks. In 1239, a mystic preacher named Baba Ishak managed to stir up rebellion amongst the Turkmen tribes. Likewise, in 1276, the Seljuk statesman Hatiroğlu Serafeddin began a revolt against Mongol—and therefore Seljuk—rule. Both uprisings were ruthlessly suppressed, and their leaders were executed.

A series of internal struggles for power among members of the Seljuk Dynasty ultimately contributed to the state’s disintegration in 1308. After the downfall of the Seljuk Dynasty in 1308, the Second Beylik Period began as several chieftaincies, including the Ottomans and Karamanids, vied for power for the next two centuries.