Shogun is the second adaptation of the 1975 novel by James Clavell about the first Englishman who visited Japan and was made a samurai by the third feudal lord aiming to unify Japan after centuries of civil war. Going by just these broad strokes, the show is quite historically accurate. However, the characters have all had their names changed, with the real-life William Adams being rechristened to John Blackthorne and feudal lord Tokugawa Ieyasu becoming Yoshii Toranaga. A closer look reveals a few more historical discrepancies, both big and small.

William Adams vs. John Blackthorne

Shogun is not a documentary. Beyond not being insultingly inaccurate about Japanese culture, it has no obligation to be a history lesson with high production values. Its primary goal is to be an entertaining story, and judging by the number of awards that the show has won, it has succeeded in that. And yet, a lot of fans of Shogun will naturally wonder how much of the series really happened. We will examine this through the lens of the show’s three main characters, starting with John Blackthorne.

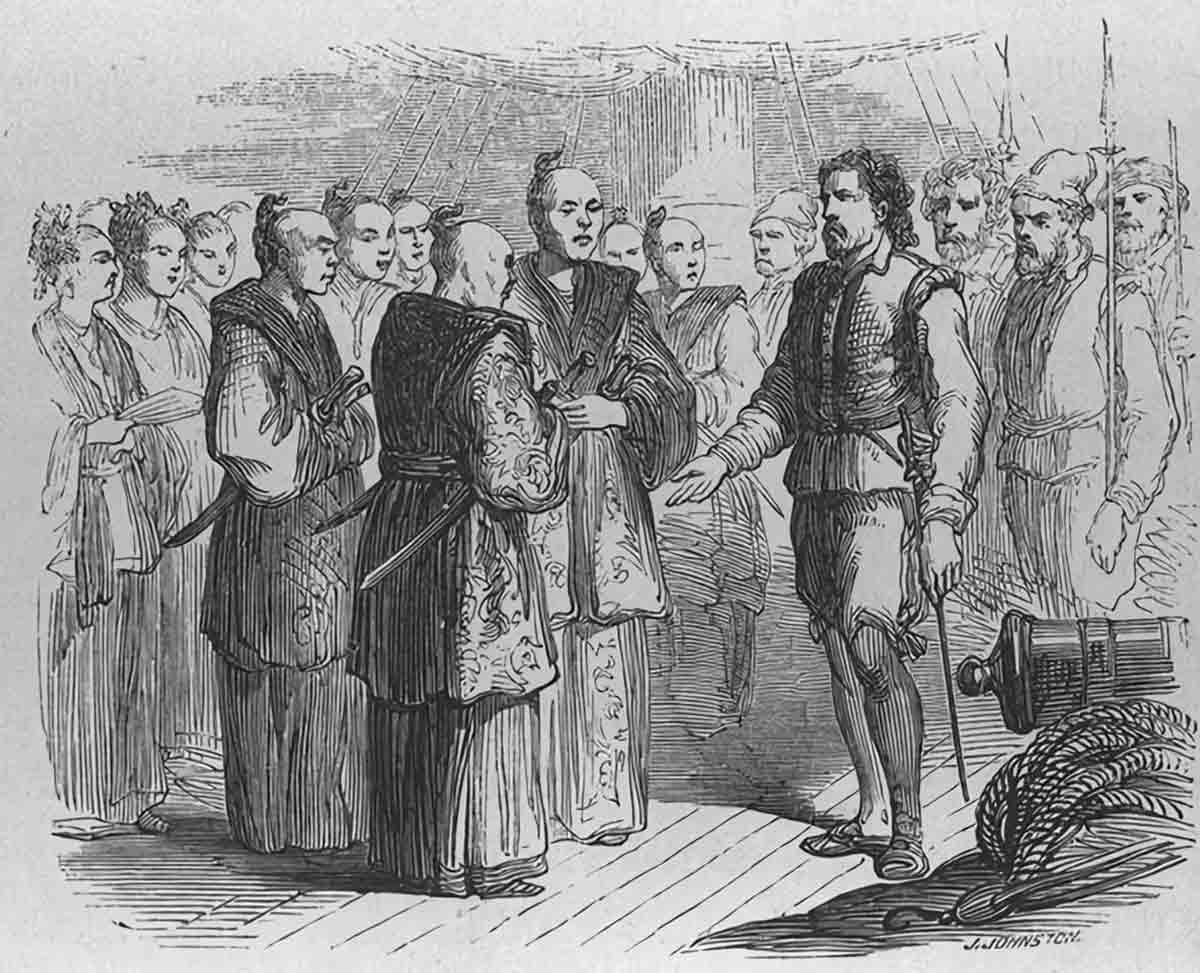

Blackthorne is based on William Adams, a real-life English navigator who arrived in Japan in 1600 when his Dutch vessel, Liefde, came ashore in Kyushu, one of the four main Japanese islands. Just like in the show, his crew was initially detained while the local Jesuit priests urged the authorities to execute them. The hostility between the Portuguese missionaries and Blackthorne is probably one of the most realistic elements of the show. According to the 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas that divided the world between Spain and Portugal, the Portuguese laid claim to Japan and were not willing to share it with Protestant nations like England or the Netherlands.

In the spirit of fairness, it is worth pointing out that they were right to worry as, after things settled down for Adams in Japan, he made contact with the Dutch East India Company who quickly sent trading ships to Japan. In 1641, after Catholicism had fallen out of favor in Japan, the Protestant Netherlands became Japan’s only source of contact with the outside world through the artificial island of Dejima in Nagasaki. But back to Adams’ story.

Managing to secure a meeting with Tokugawa Ieyasu—who, like Toranaga, was consolidating power at the time and preparing for the final battle with his enemies that would result in the creation of the Tokugawa shogunate—Adams managed to escape death and found his way into the feudal lord’s service. Unlike in the show, though, his later life was relatively drama-free. Adams shared with Ieyasu his knowledge of shipbuilding and navigation and was put in charge of some naval construction projects. He might have helped influence some of Japan’s policies concerning the outside world by providing information about the political situation in Europe, but he was far from being Ieyasu’s close confidant or a minister in the government. He definitely did not square off against ninjas or other assassins.

Blackthorne’s cultural assimilation into Japanese society, however, has a historical basis as Adams learned to speak Japanese, married a Japanese woman, and took on the Japanese name of Miura Anjin (The Pilot of Miura). While he was made a samurai, he was never part of the ruling class. Due to his foreign status, William Adams always remained just on the outside of Japanese society; close enough to get a good look at it (the letters he wrote in Japan are important sources for historians) but not close enough to make any substantial contributions to it outside of trade and maritime navigation.

Hosokawa Gracia vs. Toda Mariko

Playing the role of translator between Blackthorne and Toranaga and providing viewers with a fascinating look into the world of female Japanese nobles, Toda Mariko has been one of the standouts of Shogun. But was she a real person and what was her role in the Tokugawa shogunate? The answers to these questions are respectively: yes, though heavily fictionalized, and none, since she died before Ieyasu consolidated his power and started a dynasty that lasted for more than two-and-a-half centuries.

Mariko is based on Hosokawa Gracia (1563-1600), born Akechi Tama, a fascinating though tragic figure of Japan’s civil war period. She was the daughter of Akechi Mitsuhide, once a general in the service of Oda Nobunaga, the man who kickstarted the unification of Japan and whose equivalent on the show is Kuroda Nobuhisa. Nobunaga was ultimately forced to commit seppuku after being betrayed by Mitsuhide. On Shogun, the turncoat general takes a more active part in his lord’s death, which brings dishonor on him and forces him to kill his entire family and then himself. Mariko was then forced to marry the brutish Buntaro as punishment for her father’s crime.

This is where the show deviated the most from reality. Akechi Mitsuhide was actually killed by a peasant bandit after escaping from the forces of Toyotomi Hideyoshi (the show’s Taiko, whom Toranaga used to serve) out to avenge Nobunaga. Following her father’s death, Tama, who had been married since she was 16, was placed under house arrest by her husband, Hosokawa Tadaoki, for both of their protection. It was during that time that she converted to Christianity, took on the name Gracia, and dedicated herself to the study of Latin and Portuguese.

She did not have a chance to practice any of them with Adams, because the two never met. There was a four month window between Adams’ arrival in Japan and Gracia’s death, but it never resulted in a meeting between the two. Instead, Gracia chose to end her life to not become a political pawn. When Ishida Matsunari (Ishido Kazunari on Shogun) tried to kidnap the wives of the samurai loyal to Ieyasu before the Battle of Sekigahara of 1600, Gracia reportedly instructed one of her retainers to kill her. It has been suggested that she did not opt to take her life herself like so many other Japanese nobles before her because of her Christian faith. Needless to say, she was not exploded by ninjas.

The connection between Mariko and Gracia is obvious, from their Christian devotion to their linguistic abilities and being at odds with the enemies of Ieyasu/Toranaga through their familial connections. But a closer examination reveals all of that to just be surface similarities that obscure a real-life figure whose story easily rivals that of the fictional Mariko in drama and pathos.

Tokugawa Ieyasu vs. Yoshii Toranaga

There is an oft-repeated, totally apocryphal, but deeply symbolic story about Japan’s three unifiers. One version of the tale is found in Taiko, a fantastic historical novel by Eiji Yoshikawa. The story goes that the three men were asked what they would do if they had a bird that would not sing. Oda Nobunaga supposedly said: “Kill it.” Toyotomi Hideyoshi supposedly said: “Make it” or “Make it want to sing,” while Tokugawa Ieyasu said: “Wait.” While fictional, it does get to the heart of who Ieyasu was as a person, especially around 1600.

Like the real Ieyasu, Toranaga is portrayed on Shogun as a man of great patience and quiet cunning. A shrewd navigator of the complex world of late 16th-century Japanese politics, he knows exactly when to apply pressure, when to be merciful, and how to properly utilize every person in his orbit to achieve his own goals. In all those regards, Shogun did a pretty good job portraying the future founder of the Tokugawa Shogunate. If there is any criticism that can be levied against Shogun, it is maybe that it has made Toranaga a little too serious and ignored all the fun (albeit probably apocryphal) stories in Ieyasu’s biography.

There is a legend that, in 1573, Ieyasu stopped at a teahouse while retreating from the Battle of Mikatagahara, when suddenly he got word that his enemies were closing in on him. Making a run for Hamamatsu Castle, he was allegedly stopped by the teahouse’s elderly owner and made to pay his bill in front of his soldiers. That is apparently the etymology of the Zenitori area of modern-day Hamamatsu City, which literally translates to “The Taking of the Money.” Whether true or not, it is what has been told about Ieyasu, showing that in the eyes of his Japanese countrymen, there was a lighter side to him.

There is also this: Ieyasu cut his teeth as a military commander while fighting Buddhist zealots known as the Ikko-Ikki in Mikawa, which today makes up the eastern part of Aichi Prefecture in central Japan. The Ikko-Ikki were a powerful populist movement in 16th-century Japan and while they primarily recruited their “holy warriors” from among peasants, some samurai did join their ranks. In Mikawa, one of the old centers of Ikko-Ikki activity, this also included some of Ieyasu’s own retainers, which could have shaped his later views on religion and the value he placed on loyalty.

In the end, the Daiju-ji temple in Okazaki sent Ieyasu a regiment of warrior monks to help defeat the Ikko-Ikki. As part of the ensuing peace agreement, Ieyasu agreed to restore the Ikko-Ikki compounds to their original state. So he burned them down, arguing that an empty field was their original state (Turnbull, S., p. 17). This dark sense of humor could really have completed the portrayal of Toranaga in Shogun.

But this might be unfair criticism, especially given that the entire first season of Shogun is only 10-episodes long and its action takes place within less than one year. In that context, Toranaga is a good portrayal of Tokugawa Ieyasu (though, once again, he did not fight ninjas). The show has already deviated somewhat from the novel, and since it uses flashbacks, perhaps in Season Two we will see more fleshing out of Toranaga and more details about Ieyasu shrouded by the thin veils of fiction.

Works cited:

Turnbull, S. (2008), Japanese Warrior Monks AD 949 – 1603. Osprey Publishing.