The term “Abrahamic Religion” refers to the shared figure of Abraham, patriarch of the major monotheistic religions: Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Abraham’s presence in the holy texts of monotheism signifies shared ancestry and a degree of commonality. Many contemporary philosophical ideas about individuality, selfhood, and humanism have roots in Abrahamic religion. Conversely, the “big five” non-Abrahamic world religions and philosophies: Buddhism, Confucianism, Daoism, Hinduism, and Zoroastrianism offer rich traditions and religious philosophies that expand our understanding of human existence, ethics, and the cosmos.

1. Buddhism: The Four Noble Truths

Around 2,500 years ago, Siddartha Gautama, a young man from modern-day Nepal, set out on a quest to understand the nature of reality and the human condition. He observed that life was replete with suffering and sought a way to overcome it. Gautama passed south over the Himalayas and spent six years living as an ascetic, before sitting in deep meditation beneath a pipal tree, where he reached enlightenment and became a Buddha at the age of 35.

Having reached Nirvana, free from suffering and the cravings of earthly desire, he shared the insights of his enlightenment through the four noble truths. The essence of Buddhism is contained within these four truths:

- The truth of suffering (Dukkha): suffering is an inescapable fact of life

- The truth of the origin of suffering (Samudaya): Suffering arises from hatred, ignorance, and greed within the human mind

- The truth of the cessation of suffering (Nirodha): it is possible to end suffering by extinguishing desire and earthy attachment

- The truth of the path to the end of suffering (Magga): The eightfold path is the Buddha’s recipe for the end of suffering

Nirvana, a state of mind—or enlightenment—is free from negative emotions and fears and characterized by absolute compassion for all beings.

In his quest to overcome the suffering of existence, the Buddha realized that both the external world and our internal states are ever-changing. This led him to reject the notion of a permanent self. Identification with the self—the “I”—was an illusion, in so far as everything in existence was by definition impermanent. By freeing ourselves from the illusion of a permanent “I” the Buddha believed that we can achieve universal liberation from the suffering of the world.

2. Confucianism: Ethics and Social Harmony

Confucius was born into a noble family but following the premature death of his father grew up in poverty. Through the help of a wealthy friend, he was able to study at the imperial archives of the royal court. His philosophy, developed during the chaotic era of the Warring States Period in 6th century BCE China, focused on the creation of a just society through the power of the past, the family, and education.

Confucius emphasized the importance of the family as the foundation of ethical living. He believed that one should honor their elders as well as their ancestors, for to live well, was to show respect to the living, as well as the dead. The ultimate aim of human flourishing, according to Confucius, is achieved through living within an ethical community of people who share a commitment to ethical self-cultivation.

Human character, formed within the family and through education, was, for Confucius, dependent on the mastery of ritual practice (li), which led to the highest moral good (ren)—often translated as happiness, benevolence, or humanity. He believed that a person cultivated in this way orientates themself to help others and guides them through moral inspiration.

While Confucianism does not involve the worship of gods it has temples dedicated to the spirit of Confucius and the study of his ideas. The oldest record of Confucius’s life and ideas, The Analects, was compiled about a century after his death. When asked if he could summarize his thoughts on human virtue and good moral character in a single sentence, he is said to have replied: “What you do not wish for yourself, do not do to others.” Confucius’s influence on China and the wider world has been immense.

3. Daoism: Harmony With Nature

Daoism (sometimes “Taoism”), which is often associated in the West with the symbolism of Yin and Yang and the practice of Feng Shui, is a complex religious philosophy founded by Lao Tzu around the 6th century BCE.

According to legend, after being stopped at the western border of imperial China, Lao Tzu was recognized by the guards as the master sage and archiver of the Chinese imperial court. At the guard’s request, he stopped for the night and wrote down some of his wisdom. The result was the Daodejing (The Book of the Way), the most revered text of Daoism.

The Daodejing teaches that flourishing comes from attunement to the rhythms of nature and the discovery of tranquility, harmony, and contentment within oneself. At the heart of Daoism is the concept of the Dao, meaning “the path” or “the way.” The Dao is described variously as “empty,” “non-being,” “endless flow,” “of inexhaustible energy,” and “the bottomless”—the origin of all things. It is linked to the idea of a correct moral path but also to the natural order of the universe.

Thus, more than a moral code, the Dao is underpinned by the idea that there is a natural way that the universe operates. In this light, Daoism advocates for “effortless action” (wu-wei) as the key to a flourishing life. Daoism, in this regard, resembles an ancient self-help guide. The universe has its path, if you flow with it, you will be well in life. If you don’t, you will find obstacles and trouble ahead.

Daoism includes the earliest reference in Chinese culture to meditation and details the idea that physical exercise can help one focus on the Dao and move away from the indulgence of the senses. Unlike the ordered world of Confucius, it pivots on the notion that there is a way to flourish in life that doesn’t rely on formalized rules.

4. Hinduism: The lesson of the Bhagavadgītā

The term “Hindu” originally referred to the people living beyond the Sindhu (the Sanskrit name for the Indus River). By the 14th century, it was being used in Mughal sources to describe all those living beyond the Indus who were not Muslims (Thapar, 2014, p. 10).

Today, Hinduism represents a diverse way of life for about 80% of India’s 1.4 billion people, encompassing various sects, lineages, and communities engaged in a wide range of complex idiosyncratic expressions and practices. Across the subcontinent and beyond, a whole raft of festivals, holy sites, shrines, gods, and pilgrimage routes are in circulation, shared, and celebrated by some and relatively unimportant to others. Key concepts include dharma (duty, morality, or “way of life”); karma (the principle of cause and effect); samsara (reincarnation); and moksha (liberation).

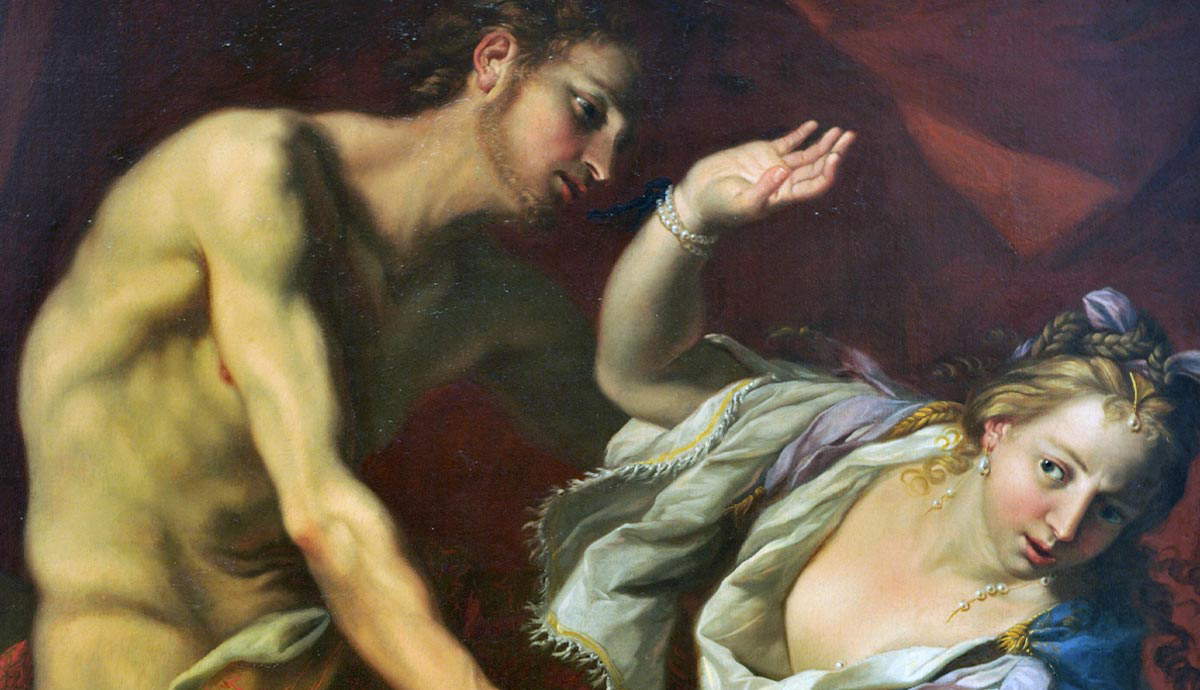

The most well-known and arguably most important Hindu scripture is the Bhagavadgītā. Comprising 700 verses over 18 chapters, the “Gita” is a dialogue between the warrior prince Arjuna and the god Krishna on the battlefield of Kurukshetra. Arjuna, filled with doubt and moral dilemmas about the prospect of waging war, seeks the counsel of his charioteer, Lord Krishna, who in turn imparts spiritual wisdom and guidance. Krishna advises Arjuna on duty, righteousness, and liberation, ultimately urging him to fulfill his duty as a warrior without attachment to the results.

The Bhagavadgītā teaches engagement with the world through non-attached action—the necessity of transcending concerns with the results of action by becoming fully immersed in the activity of one’s craft or purpose. In this context, we might connect the self (ātman) to Brahman, the ultimate reality of the universe.

2. Zoroastrianism: The Path to Righteous

The ancient Persian religion of Zoroastrianism is non-Abrahamic, though it is the world’s first monotheistic creed. Many scholars believe that Zoroastrianism influenced Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, and in particular, introduced the idea of hell into the Abrahamic tradition. At the heart of Zoroastrianism is the concept of truth and the direction that people must do good things, hear, and see good things to win the battle against evil.

Zoroastrianism emerged around 3,500 years ago in ancient Persia through the teachings of the prophet Zarathustra. For over 1,000 years Zoroastrianism was the most powerful religion in the world. Once the state religion of Persia, the Muslim conquest between 633 and 651 CE led to its decline. The largest population of modern-day Zoroastrians are the Parsis, who emigrated from Persia to India to escape religious persecution after the Muslim conquest.

Born into the Bronze Age polytheistic culture of Northwest Iran, aged 30, Zarathustra experienced a divine vision while partaking in a pagan purification rite. His vision revealed one true god, the “wise lord,” Ahura Mazda, creator of the universe, and seven holy immortals, or divine spirits (Amesha Spentas) through which humans could come to know god. Ahura Mazda, the benevolent god, was set against a single adversary, the demon spirit Angra Mainyu, the originator of death and all that is evil.

The core tenet of Zoroastrianism is thus the idea of one god and one demon; two spirits, or wills—one god and one force of total negativity, to be resisted at all costs by man. The task of humankind is to follow the path of righteousness and truth to overcome evil, the purging of evil is not the task of a messiah or god, but the everyday task of ordinary people, by good deeds and leading a truthful life.