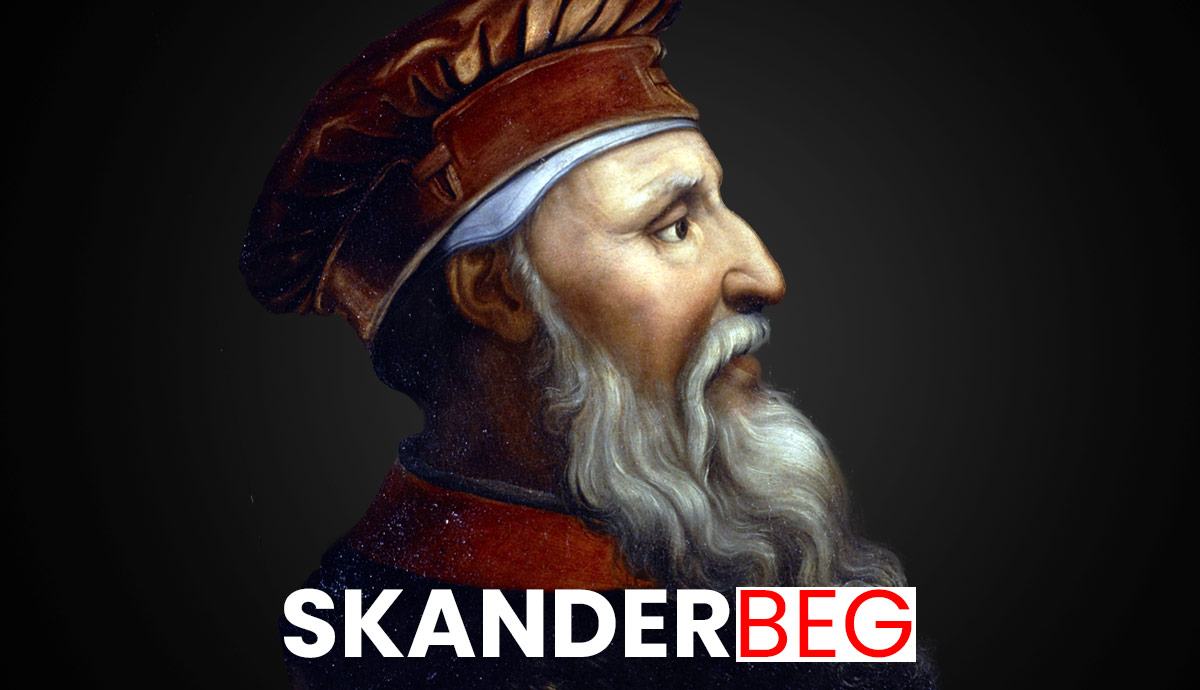

During the 15th century, as armies of the Ottoman Empire carved their way through southeastern Europe, Skanderbeg was one of the most famous men on the continent. An Albanian nobleman who began his career as an Ottoman commander, Skanderbeg raised the flag of rebellion and brought together the Albanian lords under his banner. A skilled warrior and diplomat who knew how to make use of limited resources, Skanderbeg won remarkable victories and held back the Ottoman tide for a quarter century.

Lord of Albania

On March 2, 1444, a group of lords from present-day Albania gathered at the Cathedral of St. Nicholas in the ancient city of Lezhë, then under Venetian rule. Since the mid-14th century, the armies of the Ottoman Empire had been conquering their way through the Balkan peninsula. Faced with overwhelming military force, many Albanian nobles submitted to Ottoman rule in the early 15th century. Those who attempted to resist the Ottomans often found themselves facing Ottoman armies commanded by fellow Albanians.

With Venetian permission if not encouragement, the Albanian lords formed an alliance known as the League of Lezhë and chose as their leader a man named Skanderbeg, who until very recently had been fighting for the Ottomans and owed his name to the Turks. Skanderbeg, whose Albanian name was Gjergj Kastrioti, henceforth referred to himself as Lord of Albania. He was a talented military commander and an inspired choice as leader of the Albanian resistance.

Over the next 25 years, Skanderbeg would achieve renown throughout Europe as he inflicted a string of defeats upon much larger Ottoman armies. His success on the battlefield at the head of an army that rarely exceeded 20,000 men won him diplomatic support from the Pope and other rulers in Italy. Although his battle record was not faultless and his allies were prone to deserting him, Skanderbeg ensured that the Ottomans would not subjugate Albania as long as he lived, winning crucial time for Italian and central European states to strengthen their defenses.

Iskander Bey

Gjergj Kastrioti was born in 1405 as the youngest son of Gjon Kastrioti, an Albanian lord who ruled over parts of northeastern Albania. As the Venetians, Serbians, and Ottomans vied for control of the region, Gjon regularly switched his political and religious allegiances. In the process, he expanded the family domains and served as lord of Krujë, a mighty hilltop fortress some 20 miles north of Tirana, the capital of modern Albania.

Under the Ottoman system, it was common for the sultan’s Balkan vassals to send one or more of their sons as hostages to be educated at the Ottoman court. Since the Ottoman victory at the Battle of Kosovo in 1389, most Balkan lords paid nominal fealty to the Ottomans, and in 1409, Gjon may have sent his eldest son, Stanisha, to the Ottoman sultan. While Skanderbeg’s early biographers claimed that Gjergj was sent to the Ottoman court in Edirne as a child, he does not appear to have entered Ottoman service until the 1420s, after Sultan Murad II came to power following a civil war and renewed Ottoman offensives in the Balkans. In 1430, the Ottomans sacked much of Gjon Castrioti’s domain as he attempted to maintain neutrality between the Venetians and the Turks.

According to the traditional narrative set out by Skanderbeg’s earliest biographer, Marin Barleti, Gjergj Kastrioti demonstrated his military abilities and was given the noble title of Iskander Bey or “Lord Alexander” with reference to Alexander the Great. There are few documentary records of Skanderbeg’s service in the Ottoman army, but in 1438, the Ottomans granted him a portion of his father’s land, presumably shortly after Gjon’s death.

Scourge of the Turks

In early November 1443, an allied Serbo-Hungarian army captured the Ottoman stronghold of Niš in southern Serbia. Skanderbeg used the opportunity to desert the Ottomans. He led 300 men to Krujë and took possession of the fortress on November 28. As the Ottoman forces retreated for the winter, Skanderbeg occupied a string of Ottoman fortifications up to Svetigrad on the Albanian-Macedonian border.

After forming the League of Lezhë, Skanderbeg prepared to confront a renewed invasion by Murad II in the spring of 1444. On June 29, the two armies met at the Plain of Torvioll in eastern Albania, where Skanderbeg enticed the enemy to launch a frontal assault before sending in his cavalry concealed amongst the woods on the Ottoman flank and rear. Skanderbeg’s victory brought him to international attention and encouraged Pope Eugenius II to devise a plan to evict the Ottomans from Europe. However, János Hunyadi’s Hungarian army was defeated in November after the neutral Serbian ruler prevented Skanderbeg from joining his ally.

Having regained the initiative, Murad offered Skanderbeg autonomy within the Ottoman Empire, but the Albanian leader refused and defeated two further Ottoman invasions in 1445 and 1446. Skanderbeg’s success threatened Venetian interests in Albania. In 1447-48, the two parties fought a brief war that was ended by a peace agreement in October 1448, which formally recognized the Albanian League as an independent entity. However, the Venetians refused to supply troops for Skanderbeg in his continued fight against the Ottomans.

A Desperate Siege

After making peace with Venice, Skanderbeg was free to lead his troops to raid Ottoman Macedonia. Such incursions could not fail to provoke a response from the sultan, who was now convinced that he would have to lead the Ottoman army in person to defeat the rebellious Albanians. In May 1449, Murad appeared beneath the walls of Svetigrad and prepared to lay siege to the fortress. The sultan’s army was far larger than any Ottoman force Skanderbeg had faced before, and the Albanian commander waited until June 22 before launching a surprise night attack. While Skanderbeg got away after securing a tactical victory, Svetigrad was running low on water and surrendered to the sultan.

The loss of Svetigrad was a bitter blow to the Albanians, and Skanderbeg retreated to his base at Krujë to strengthen his defenses. The sultan had returned to Edrine for the winter but was back to lead an army of up to 160,000 men against Krujë in the spring of 1550. With fewer than 10,000 men at his disposal, Skanderbeg left the dependable Vrana Konti in command of Krujë’s garrison and used a mobile cavalry force to carry out hit-and-run attacks against the Ottoman camp. After several failed attempts to take Krujë, Murad made diplomatic overtures, which were rebuffed. On October 26, Murad lifted the siege and returned to Edirne. After gaining this respite, in May 1451, Skanderbeg married Andronika Arianiti, the daughter of his ally Gjergj Arianiti, a powerful lord in southern Albania.

Confronting Mehmed the Conqueror

Murad II died in January 1451 and was succeeded by his son Mehmed II, an ambitious 19-year-old keen to prove himself. Although he had accompanied his father in his recent campaigns against Albania, Mehmed set his sights on conquering Constantinople, the capital of the fading Byzantine Empire. While Ottoman artillery had been too unreliable to bring down the walls of Krujë, Mehmed cast the largest cannon at that point in history and used it to tear a hole through Constantinople’s thick walls in 1453. Mehmed entered Constantinople on May 29, thus earning himself the sobriquet Mehmed the Conqueror.

Although the Fall of Constantinople was recognized as a calamity in Western Christendom, Mehmed’s preoccupation with the imperial city gave Skanderbeg respite to rebuild the Albanian League, of which several members had either become neutral or sought protection with Venice. In March 1451, Skanderbeg agreed to become the vassal of King Alfonso of Naples, who also ruled over the Spanish kingdom of Aragon. Alfonso signed similar agreements with other Albanian lords, effectively reconstituting the League of Lezhë.

In July 1455, with Mehmed distracted in Serbia, Skanderbeg took 12,000 Albanians and 2,000 Neapolitans with siege artillery to besiege the strategic city of Berat in southern Albania. Skanderbeg’s brother-in-law Teodor Muzaka, whose family traditionally ruled Berat, accepted the Ottoman garrison’s offer to surrender within eleven days if no help had come. In the meantime, Skanderbeg rode away from Berat, searching for the enemy. In his absence, an Ottoman cavalry force under the command of veteran general Isak Bey ambushed Muzaka, killing him and most of his men.

The defeat at Berat was exacerbated by the defection of Skanderbeg’s ally Moisi Arianti during the battle, while others exited the League once again. The following spring, Moisi led an Ottoman army against Skanderbeg and was defeated, prompting him to return to his old friend’s side. A much more serious blow was the desertion of his nephew Hamza Castrioti in 1457.

Hamza, the son of Skanderbeg’s eldest brother, Stanisha, had a claim to the Castrioti lands and resented his uncle’s power and fame. In May 1457, Hamza Castrioti and Isak Bey led an army of 50,000-80,000 men into Albania. In response, Skanderbeg fell back from the frontier and seemingly disappeared. With his whereabouts unknown, the Ottomans were cautious about marching on Krujë and set up camp at Albulena at the foot of Mount Tumenishta. On September 2, the Ottoman army concluded that Skanderbeg’s men had deserted him and prepared to march on Krujë. In reality, Skanderbeg had divided his forces into small columns, which marched separately towards the vicinity of Albulena. As the Ottomans broke camp, Skanderbeg’s men launched their attack and routed the enemy. Hamza was taken into captivity, and the Albanians inflicted up to 30,000 casualties on the Turks.

A Renewed Crusade?

The Battle of Albulena was one of Skanderbeg’s greatest victories, but his cause was undermined by the death of his overlord, King Alfonso of Naples, in 1458. The succession of Alfonso’s illegitimate son, King Ferrante, was challenged by rival Italian princes, and the new king requested help from his Albanian vassal. In the spring of 1461, Skanderbeg dutifully agreed to a three-year truce with the Ottomans and sailed to Ferrante’s aid in August. The arrival of the Albanians turned the tables in Ferrante’s favor since the Italian mercenary armies were afraid of doing battle with the fearsome Skanderbeg. After five months, Skanderbeg left Italy in February 1462 with Ferrante secure on his throne.

By the time Skanderbeg returned home, preparations were underway for a crusade against the Ottomans planned by Pope Pius II. The Ottoman advance into Bosnia in 1463 galvanized the Venetians into action, and that September, Skanderbeg signed an alliance with Venice. He was to attack the Ottomans in Macedonia, while the Hungarians were to move on Bosnia from the north and the Venetians on Greece in the south. Despite a promising start in 1464, the Pope died on August 14 while preparing to sail across the Adriatic to take command of the crusading armies. The crusade died with him, and the Hungarians and Albanians were left to fend for themselves.

Skanderbeg’s Final Years

In 1465, Sultan Mehmed ordered another campaign against Albania. He placed 18,000 men under the command of Balaban Pasha, the son of an Albanian farmer from the Castrioti lands who had grown up as a hostage at the Ottoman court. In April, Skanderbeg took the offensive and attacked Balaban at Valcalia near Ohrid in western Macedonia. Although the Albanians won the battle, it was a costly victory as Balaban had warned his men what to expect. As a result of stiffer-than-expected Turkish resistance, eight senior Albanian generals were captured and later executed. While Skanderbeg repulsed a renewed offensive by Balaban later in the year, it was little consolation for the loss of his lieutenants.

In 1466, Sultan Mehmed personally led an invasion force of some 100,000 men into Albania. As they advanced along the Roman Via Egnatia, the Ottomans pillaged the surrounding countryside. Mehmed established a permanent settlement called Elbasan and used it as his base for siege operations against Krujë. The Venetians were alarmed by this development and gave Skanderbeg some 15,000 men. With some 30,000 men at his disposal, Skanderbeg broke the ring of Ottoman strongpoints around Krujë and killed Balaban in April 1467. After failing to capture Elbasan, Skanderbeg was desperate for further assistance, and in January 1468, he returned to Lezhë to consult with the Venetians. He was desperately ill and died on January 17, 1468 at the age of 63. His body was buried at the Cathedral of St. Nicholas, where the League of Lezhë was founded 24 years earlier.

Albanian National Hero

Following Skanderbeg’s death, the Albanian League survived for another decade until Krujë fell to the Ottomans on June 16, 1478. Later that year, the Ottomans conquered Lezhë and desecrated Skanderbeg’s tomb. While Albania would remain under Turkish rule until 1912, the Skanderbeg legend was born in 1504 when the Jesuit priest Marin Barleti published his influential biography of Skanderbeg.

Over the centuries, Skanderbeg’s legacy continued to inspire Europeans resisting Ottoman invasions of central Europe, as well as those who wished to see the Balkans liberated from Ottoman rule. In the assessment of 18th century English general James Wolfe, Skanderbeg “excels all the officers, ancient and modern, in the conduct of a small defensive army.”

While Skanderbeg’s international fame declined with the Ottoman Empire in the late 19th century, the Albanian nationalist movement embraced him as their country’s national hero. He continued to be popular during the communist era, and an equestrian monument of Skanderbeg was erected in the central square of Tirana in 1968 upon the 500th anniversary of his death. The Skanderbeg National Memorial was built around the Cathedral of St. Nicholas in Lezhë and completed in 1981.