Accounts of the discovery of the “new world” often give the impression that Europeans’ first encounters were with small native tribes, saving major indigenous histories for large civilizations like the Aztec and Inca. In fact, the very first people the conquistadors met in the Caribbean were part of a distinct culture with its own religious mythos, political organization, advanced agricultural practices and trade routes. Today they’re called the Taíno, and while their societies may have been exterminated, their people were not.

Pre-history of the Taíno

The islands of the Caribbean were among the last bits of land in the Americas to be settled, but modern scholars estimate that as early as 2000 BCE, indigenous peoples from South America began traveling to occupy the Greater Antilles (present day Cuba, Haiti, the Dominican Republic, Jamaica and Puerto Rico) and other islands in the region. They encountered earlier foraging peoples (whose origins are debated), who were quickly replaced by the newcomers. Ultimately, scholars believe it was the Arawaks from northern South America that came to dominate the islands of the Greater Antilles, supplanting earlier indigenous settlers.

Once on the islands, their culture developed separately from that on the mainland and became what is known today as Taíno. This term, however, is not without its critics. Some scholars argue that “Taíno” was never meant as a cultural designation—it was not the name these native peoples used for themselves as an entity, but a description offered to the invaders to distinguish themselves from the warlike Caribs. “Taíno” means “the men of good.” Nevertheless, it seems the name was adopted by some Spanish colonizers. Later historians asserted that “Arawak” or “Island Arawak” would be more appropriate. Regardless, “Taíno” is still the most widely used term today to refer to the indigenous culture that dominated the Greater Antilles when Christopher Columbus arrived, and has even been reclaimed by some modern indigenous groups.

Taíno in Puerto Rico

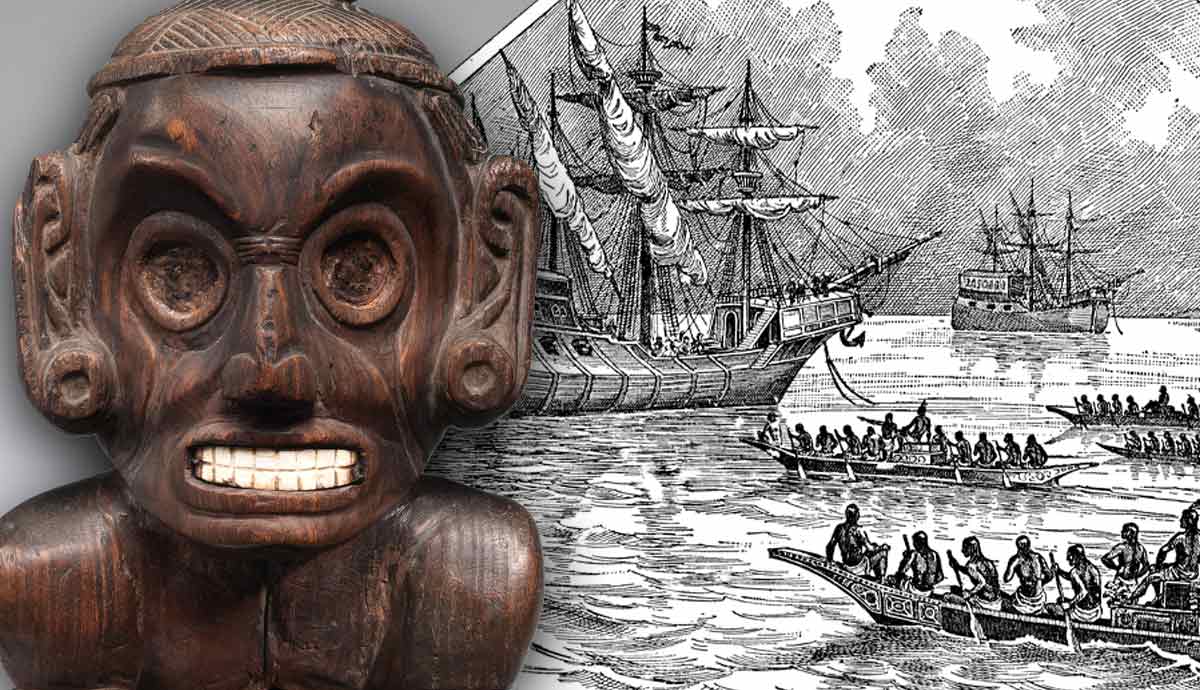

Before it was Puerto Rico, the eastern-most island of the Greater Antilles was called “Borikén” by the native population—giving rise to the term “Boricua,” used for people of Puerto Rican descent today. Largely peaceful, the island’s people practiced hunting, fishing and small-scale agriculture supplemented by plentiful gathering in the lush forests. The Taíno cultivated yuca, cotton, and sweet potato and slow-roasted food on green-wood frames over fire pits—barabicu. They navigated the waters of the Caribbean in dug out boats called canoa, carved from single tree trunks, some large enough to hold 40 people.

At the time of first contact, the leader of Puerto Rico’s Taíno was named Agüeybana. He ruled over tens of thousands of Taíno on the island, divided into approximately 20 villages. Some of the Taíno names for places on the island remain in use in Puerto Rico today: Utuado, Mayagüez, Caguas, and Humacao.

Some historians contend that the island’s native population was already in decline due to raids by the neighboring Kalinago, better known as the Caribs for whom the region is named, who called the Lesser Antilles (today the Virgin Islands, Dominica, Antigua and Barbuda, St. Kitts and Nevis, among others) home. Others suggest that intermittent skirmishes with the more warlike Caribs were not unusual and did not pose a serious threat to the Taíno way of life. Whichever is the case, the island’s location, at the intersection of the Greater and Lesser Antilles, may have made it central to interactions and exchange in the region.

Taíno Social Structures

By the 13th century CE, the Taíno had become the dominant culture in the Greater Antilles, evolving out of earlier cultures and developing the familiar characteristics of “civilized” societies: social stratification, advanced agricultural practices, denser population centers and defined political administration. Unfortunately, much of what we “know” about the Taíno is based on Spanish chroniclers whose motives were questionable at best, and whose histories are necessarily written from an outsider’s perspective. Archaeological evidence has also provided clues about Taíno customs, lifestyle and religious beliefs.

The Taíno spoke a language derived from Arawak, some of which has made its way into Spanish and even English. Though they did not have a written language, meaning they left no formal records behind, archaeological finds suggest they used a form of proto-writing, or a small collection of glyphs with specific meanings, which were reproduced in pottery, sculptures and rock art.

By the time Taíno culture reached its peak, between the 13th and 15th centuries, more advanced political structures had developed. Its people were organized into chiefdoms, cacicazgos, led by caciques, chiefs who were responsible for organizing labor, food distribution, trade and special events. Lower-level chiefs, ruling over individual villages, joined with shamans, healers and lesser noblemen to round out the nitaínos, elites, distinct from the laboring class, naborias. Taíno society was matrilineal, with positions of authority inherited from the mother’s side, and polygamous, though historians note usually only caciques could afford to have multiple wives. While the division of daily activities might be gender-based, women could also become caciques and join men in battle.

In Taíno villages, yucayeques, huts, bohíos, were arranged around a central plaza, batey, used for playing a ballgame similar to the Mesoamerican ballgame and for ritual ceremonies. The cacique, who some scholars suggest also filled a spiritual role as intermediary between earth and the cosmos, had a larger home, a caney, that was centrally located and rectangular.

Taíno Culture and Religion

Based on Spanish chronicles, quite a bit is known about what the Taíno looked like and how they dressed—or didn’t. They largely went naked, though married women sometimes wore short skirts and both men and women adopted accessories and jewelry. Their hair was worn short in the front, cut above the eyebrows (i.e., they had bangs), and they adopted a practice of flattening their foreheads, achieved by tying boards to the front and back of babies’ heads. They also might pierce their ears, noses and lower lips and wear bands or sashes on their arms or legs. Caciques wore feathered headdresses, belts and amulets for special occasions, and body paints were also commonly used, often applied with carved stamps.

Extensive details about Taíno mythology and spirituality were recorded by Friar Ramón Pané, who accompanied Columbus on his second voyage to the Antilles and lived among the Taíno on Hispaniola. Like the other soon-to-be “discovered” cultures in the Americas, the Taíno honored a pantheon of greater and lesser gods. Yócahu, the creator, was at the top, along with Atabey, his mother; various other gods and goddesses were believed to control the winds, rain, and other vital aspects of their lives. Both gods and ancestors were honored in ceremonies called areytos, which involved dancing, drumming, chanting and the use of hallucinogens (cohoba, the ground seeds of a native tree) by shamans and caciques in order to connect with the spirit world.

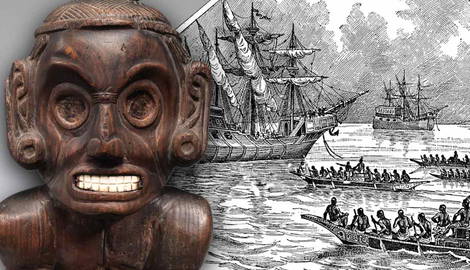

The Taíno were skilled artisans and while some objects had a utilitarian purpose, nearly everything they made was a reflection of their spiritual beliefs and mythos. They crafted pottery, jewelry, and most importantly idols imbued with spiritual powers referred to as cemí (or zemí). These could take the form of small sculptures or cotton figures as well as larger carvings, often on stone pillars surrounding the central plaza. The Taíno also crafted unique ceremonial dúhos, stools or seats carved from stone or wood, often with elaborate decoration, which their nobility would sit on during ceremonies. Instruments to inhale hallucinogens, featuring two tubes to be pressed to the nose, were also carved from wood or bone with animal or human figures. They also left behind what modern scholars have termed “vomit sticks,” also beautifully carved despite their name and usage—to induce vomiting as an act of purification before communing with the spirits.

Gold, the precious metal that instigated the deaths of millions of indigenous on the American continent, was used sparingly, reserved for caciques and nobility. Far from mining vast quantities of gold as Columbus hoped, the Taíno panned for it in streams and rivers and created a gold-copper alloy called guanin. The special gold medallion worn by caciques shared this name. Gold had no intrinsic value but was used for personal decoration.

The Fate of Puerto Rico’s Taíno

The Taíno of the present-day Bahamas were the first to encounter Columbus, but by 1493 the Spanish had made their way to Puerto Rico, marking the beginning of the end for their society. Of the Taíno people, Columbus remarked, “They were very well built, with very handsome bodies and very good faces….They do not carry arms or know them….They should be good servants.” His intentions were clear.

Historians long held that the Taíno throughout the Caribbean were essentially wiped out by Columbus’s men and the conquistadors who came after them, with both disease and enslavement decimating their numbers. In Puerto Rico, for example, census records demonstrate a dwindling native population over centuries, until 1802, when the number of “Indians” changed to zero. Yet, given the conquistadors’ penchant for sexually assaulting native women and taking them as slaves, or arguably wives, as well as the recorded practice throughout the Americas of natives disappearing into the wilderness rather than submit to the Spanish, the complete disappearance of indigenous Caribbeans seems unlikely.

Up to 90% of the indigenous population of the Americas died in the century following Columbus’s arrival, and certainly the Taíno as a society were eliminated. But DNA evidence has revealed that Taíno descendants are alive and well in Puerto Rico today, and throughout the Caribbean. A 2003 study of the island’s population revealed that 61% of those surveyed had DNA of Indigenous origin.

The rediscovery of native DNA in Puerto Rico has prompted mixed reactions. Many feel vindicated that their long-held claims of native identity have proven true. Some have pushed for a broader recognition of Taíno heritage and culture, even working to revive the extinct Taíno Arawak language. Others find such efforts divisive, arguing that the mix of cultures and ethnicities—Indigenous, African and European—on the island has created a new, uniquely Puerto Rican identity that should be celebrated.

Taíno leaders today have referred to their erasure as a “paper genocide”—people of native descent logically still existed, but by purposefully not recognizing them in records, the Spanish “disappeared” them for their own narrative purposes.