Tantra is a concept at once familiar and utterly foreign. It is everywhere and nowhere. Most of us would imagine that we have a clear idea of what Tantra is and yet many of us would be surprised about how much history and complexity lies in the philosophy and the practice. In the West, it has been considered a seedbed for dissent, a cult of ecstasy, or simply a date night for those with a spiritual bent who want to spice up their love lives. It has been adopted with enthusiasm and simultaneously whitewashed, appropriated, and abused.

What Is Tantra?

To look at Tantra in the modern world we need to understand what Tantra is in the first instance. A task that is, on its own, tremendously challenging. “Almost every study of Tantrism starts with an apology” (The Roots of Tantra, 2012). The term “tantrism” is a Western label for a system of thought expressed through a series of texts called the “Tantras.” How old tantrism is, whether tantrism was ever really a separate religious movement, and what Tantra even is, however, remains up for debate.

Tantra is an accumulation of practices and ideas that have been picked up haphazardly at different times, different places, and by different individuals. It has influenced monastic religions in the form of Tantric Hinduism and Tantric Buddhism and yet Tantra itself is non-monastic and has been passed from guru to guru over the centuries. It could be argued that Tantra is as the tantric practitioner does but for the sake of this article, we need to work a little harder than that.

At the heart of Tantra is the notion that the world was brought into being by the sexual union of Shiva and Shakti. Shiva is representative of pure consciousness while Shakti represents the creative force. Shiva represents the masculine, which is essentially inert without the creative power of the feminine. As it is the feminine that gave power to the act of creation within Tantra, it is the feminine that is most intimately connected with the physical realm.

Tantric mythology focuses on the worship of female deities and yoginis. As a non-monastic tradition, Tantra gives a pathway to enlightenment that does not turn its back on normal human life. It is possible to experience intimacy power and financial gain in this lifetime without sacrificing the goal of enlightenment in the next. We can become closer to the divine while still living and feeling.

Tantra uses a system of meditation, movement, chanting, visualization, transgression of norms, and sexual ritual (often purely symbolic) to free the blockages in the body that prevent divine power from flowing within us, ultimately leading us back to God.

The Roots of Tantra

Tantra first became popular during the 6th century BCE when it transformed approaches within both Hinduism and Buddhism. It appeared during a period of great political upheaval and gave rise to a dramatic increase in Goddess worship. Its influence can be felt in many aspects of South Asian culture and philosophy. But, while Tantra may be exploding into popular thought and imagination at this time, its true roots are far older.

M.C. Joshi (The Roots of Tantra, 2012) finds the roots of Tantra in ancient practices of goddess worship that have existed within Indian tradition since the beginning of time. Likewise, religious scholar Douglas Renfrew concurs, that Tantric thought existed long before the Tantras were ever created. The specific shape and origins of Tantra are almost impossible to define.

Tantra is ancient and pervasive, its imagery is powerful, and its appeal is multi-faceted and seductive. Western culture can’t seem to leave Tantra alone, we are drawn back to it, time and again. But this complex system of thought has been constantly subjected to misapprehension and misappropriation even by those who believe that they are enthusiasts.

Tantra and Rebellion During the British Raj

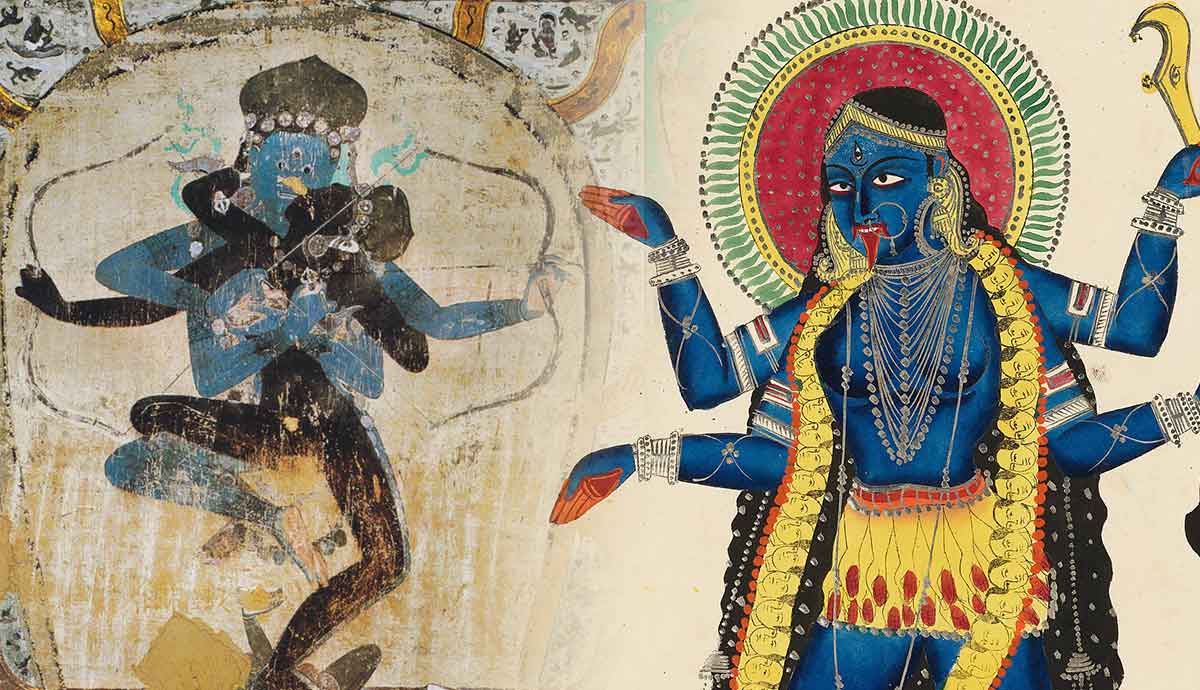

When the British Raj encountered Tantra they were horrified by images which, to them, appeared both indecent and terrifying. The British saw it as a justification for their perception of Indian culture as savage and primitive. Art and sculpture depicting the tantric goddess Kali standing on top of Shiva’s apparently dead body, blood dripping from her lips, severed heads worn as a garland around her neck, and a sword raised in her hand, were taken as indicative of black magic. Think about Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom. Worship of the goddess Kali was regarded as some kind of evil cult.

Within tantric mythology, the rage of Kali is directed at the evils and demons that torture the material world, her weapon is a sword of wisdom and the heads around her neck represent the vanquished egos of her followers. Kali will drink the poison from your veins and help you to cut away the elements of your ego that no longer serve. She is a fierce mother who will fight for you and your spiritual path, a subtlety that was rather lost upon the British who felt the need to attempt to “save” the Indian population by forcing Christianity upon them.

During the tension caused by the British occupation of India, Kali became representative of a different fight. The fight for a free India. She was reimagined as a figurehead for freedom fighters, her new enemy was the British governors and armed forces that enslaved her land. She was even once portrayed with the severed heads of the British around her throat. Both sides of the conflict embraced such imagery as symbolic of the battle between them.

Tantric imagery also found a home in the work of many South Asian artists both before and after independence from British Rule in 1947, as modern styles were created using influences from the pre-colonial art of the past.

Tantra and the Rise of Counterculture

In the ‘60s and ‘70s, Tantra was again reimagined as a cult of ecstasy in the US and UK. During the burgeoning wave of counterculture that preached peace, freedom, free love, and respect for nature, Tantra found its place as yoga and meditation also found their footing in a movement intended to bring about liberation from the status quo. It was the inspiration behind controversial poetry and photography as well as the famous lips logo for the Rolling Stones album Sticky Fingers.

In South Asia, an artistic movement known as Neo-tantrism used imagery from the mandalas to create visual art intended to express unity and freedom. This term was also adopted to name a new brand of tantrism which used Vedic influences to create a spiritual and connected vision of sexuality as something greater than a moment of heated passion.

Tantra, Feminism, and Cultural Appropriation

Most recently, Tantra has been brought into the public consciousness again as part of the rise of the feminine that we are seeing today. In Burning Woman, Lucy H. Pearce uses imagery of Kali amongst other mythic feminine figures to open up new conceptions of feminine archetypes, outside of the classically accepted Jungian comprehension of femininity, and she encourages the use of these as a way for women to explore notions of imprisonment, empowerment and rage. Uma Dinsmore-Tuli PhD, on the other hand, has spent several years expounding the notion of Yoni Shakti, or womb yoga, which uses Tantric thought in a system of yoga designed to support women through multiple stages in life.

Currently, however, it is necessary to look at these movements and question the degree to which yoga and Tantra have again been appropriated by Western minds and adapted for our own use. While practitioners may have greater and greater access to gurus from South Asia, the need to make their practice as teachers make economic sense will often force them to create a tantric practice that has been moderated to meet the expectations of their audience.

While we may be well-meaning, are we stumbling into the trap of forgetting to pay humble reverence to the long history of the practices we so admire? There is, simultaneously, a growing movement to prevent dominant powers from controlling the narrative and to return Tantra and yoga to a more respectful place.

As Western practitioners grapple with how to teach with cultural appreciation rather than cultural appropriation, what does that mean for our evolving relationship with Tantra in Europe and the Americas?

Tantra: A Possible Future

While we would like to imagine that the process of decolonization is complete when political powers remove themselves from an occupied space, the reality is that decolonization is a slow and painful process that forces members of the colonizing power to confront themselves again and again. Over and over, we must force ourselves to look at the ways in which we use elements of colonized cultures and whether we do so from a place of respect or like children picking up an exciting new toy.

Tantra is still everywhere and nowhere and it is possible that the West will never have a truly authentic experience of tantric belief as we have not been raised within the cultural paradigms through which Tantra flows intrinsically not separately. All religious and spiritual movements that stand the test of time, however, will always evolve with the changing needs and perspectives of their adherents. As we work to change our own perspectives on cultural power and appropriation our relationship with Tantra will grow and maybe, if Tantra is as the tantric practitioner does, and we approach it with respect and reverence, we may be halfway there.

Bibliography

What is Tantra?, by Imma Ramos, The British Museum

The Roots of Tantra, Katherine Anne Harper and Robert L. Brown, 2012