summary

- Hatshepsut didn’t erase him, she likely used his memory and name to legitimize her own powerful reign.

- His badly damaged mummy suggests a frail, sickly ruler, but this remains a point of scholarly debate.

- The long-lost tomb of Thutmose II was recently found, but it was empty due to ancient looting and flooding.

- Thutmose II was not the intended heir, only becoming pharaoh after the unexpected death of his older brother.

Thutmose II might be the most enigmatic Pharaoh of the 18th Dynasty, because there remains a multitude of questions, theories, speculations, and arguments about him and his reign! Some see him as a mere “placeholder” in the line of his illustrious family. Others point out the successful crushing of revolts in the Levant, Nubia, and Sinai, and no signs of problems in the Egyptian homeland.

The Story of Thutmose II

Relatively little is known for sure about Thutmose II in comparison to some of the pharaohs of the New Kingdom. Nevertheless, the Thutmosid Dynasty, to which he belongs, is well documented. It included several of the most famous pharaohs, like Thutmose I, Thutmose III, and Hatshepsut. Inscriptions of Thutmose II’s exploits and monuments from his reign are very scarce, leading to further speculation about the reason for it.

Early on, it was assumed that the female pharaoh Hatshepsut had deliberately erased Thutmose II’s name and image from his monuments and replaced some with her own. In-depth analysis and common sense, though, tell us that this is unlikely—at least to the extent previously thought. Several modern scholars have pointed out reasons for Hatshepsut to have used his memory to legitimize her rule.

In fact, there is definitive proof that she had his name and image inscribed on her mortuary temple and a gateway built at Karnak. His name is also inscribed on two fortresses and in rock reliefs, commemorating victories at Kumma and Semna in Nubia. At Elephantine near Aswan, his name is inscribed on temple walls.

Furthermore, ancient Egyptians often reused building materials from buildings built by even relatively close predecessors. The famous limestone block depicting a kneeling Thutmose II was, for instance, discovered by modern renovators as part of the third pylon at Karnak built by Amenhotep III.

Bloodline and Heritage

Thutmose II was not raised as the crown prince. Hereditary succession from father to firstborn son was, with few exceptions, firmly entrenched by this time. Thutmose II had an older brother who died before the death of their father, Pharaoh Thutmose I (some sources say two older brothers). Thutmose II’s mother was a minor wife or concubine, Mutnofret, from outside the royal house.

His ascent to the throne was almost a replica of Thutmose I’s rise to the throne, who also inherited the throne after his older brother/s died. Both Thutmose I and Thutmose II amplified their status to inherit the throne by marrying great royal wives closer in direct line to the throne.

The very fact that the famous archaeologist, Flinders Petrie, discovered the foundations of a mortuary temple for Thutmose II’s older brother, Wadjmose, on the West Bank at Thebes, indicates that he was most likely the designated crown prince. Unprepared Thutmose II was thus thrust into the role after his death. The ages of both Wadjmose and Thutmose on this occasion are unknown.

It is interesting to note that, although earlier Egyptologists believed that Thutmose I was not related to his predecessor, Amenhotep I, DNA tests have since proved that he was his son! Likewise, DNA tests confirmed Thutmose II’s parentage as well, although Egyptologists, with few exceptions, were already fairly certain of that.

The Broken Mummy of Thutmose II

Thutmose II’s mummy was discovered in a hidden rock-cut cache (named DB320) of reinterred royal mummies near Deir el Bahri by archaeologists in 1881. Thutmose II’s mummy was identified among them through his name on his coffin and his mummy wrappings. His face also bore a remarkable resemblance to that of his father, Thutmose I, who was also among these mummies. Scholars established from texts that the mummies were removed from their original tombs during the 21st Dynasty by the priests of the Amun Temple to safeguard against natural damage and tomb robbers. Tomb robbing was rampant during this dynasty, which fell in the Third Intermediate Period.

The mummy was not in its original coffin when discovered. The mummy was unwrapped and catalogued around 1886 by Gaston Maspero. It was immediately obvious that tomb looters had already plundered and wildly damaged it before it was rewrapped and moved to the safe Cache DB320 during the 21st Dynasty. X-rays during the 20th century showed, inter alia, a completely broken-off right leg, and that his ribcage had been broken open.

There was also water damage to the mummy. Forensic investigators guessed the age at death of the frail, thin man to be around 30 years old. His skin is badly scarred and scabby, and he is bald in patches. Scientists concluded that he had been frail and sickly all his life, and he had died from unidentified health problems.

This assumption is disputed by others, who point out that the frail state of the mummy does not necessarily point to a weak ruler or a lifelong illness. Modern DNA and other forensic tests have not been published, but there is speculation that he carried markers of Marfan Syndrome. He possibly also had Tuberculosis.

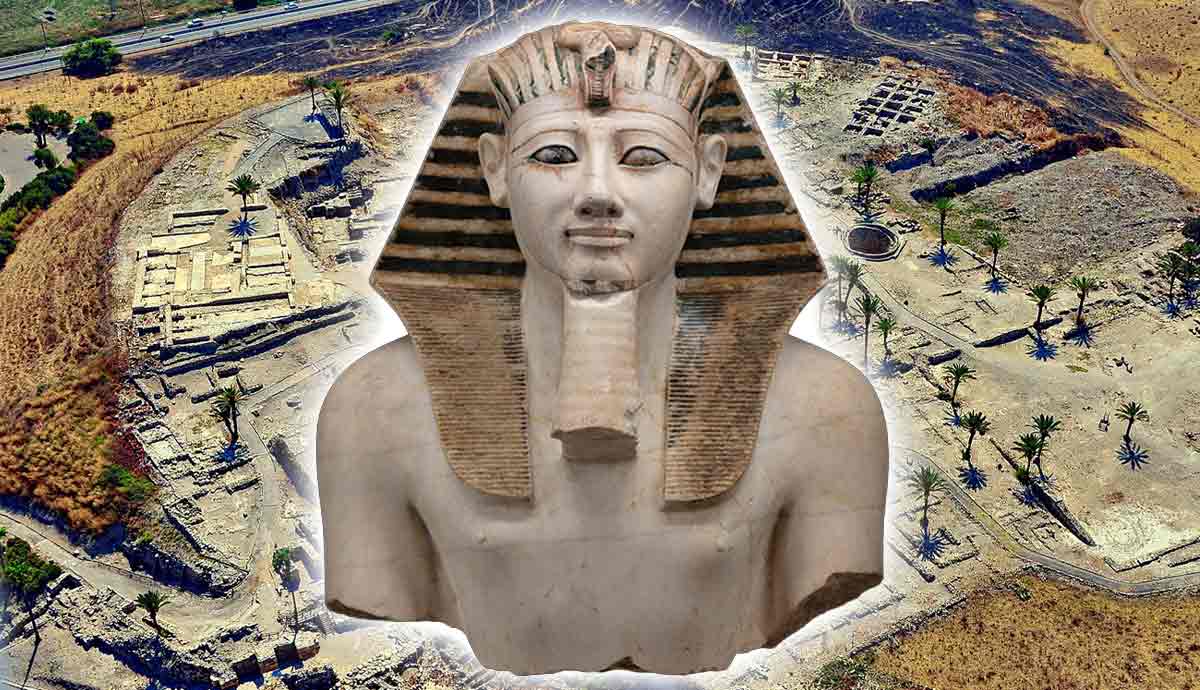

The Lost Tomb

Archaeologists had been searching for Thutmose II’s tomb for over a century when its entrance was discovered in October 2022. The tomb was close to that of Hatshepsut and several wives of Thutmose III, and it was assumed that it belonged to another royal woman.

The British New Kingdom Research Foundation and the Egyptian Antiquities Ministry’s team spent many long months carefully removing the mass of debris from the entrance. It was identified as a pharaoh’s tomb when lead Egyptologist, Piers Litherland, saw the steep staircase and wide passage leading to a chamber. Typical of pharaonic tombs, the ceiling of the chamber was painted blue with yellow stars.

Alas, the tomb was empty except for broken pottery and alabaster jars. The names of both Hatshepsut and Thutmose II were found on the broken alabaster jars. The water damage, which was similar to that of the wrapped DB320 Thutmose II mummy, and his name on broken vessels, helped Pierce Litherland to identify the tomb.

Thutmose II’s tomb was one of the few major Pharaonic tombs discovered after the sensational find of Tutankhamun’s undisturbed tomb. The news was published in February 2025, announcing that Egyptologists had now discovered the tombs of all the 18th Dynasty’s pharaohs! It should be mentioned, though, that nobody was aware of Tutankhamun’s existence until his tomb was discovered, so maybe, however unlikely, there is another inconspicuous pharaoh’s tomb waiting to be found?

There are theories that there is a second tomb of Thutmose II still to be discovered. The speculation is that Hatshepsut had already removed his body from the recently discovered tomb around six years after his death due to flood damage. This first tomb was built behind a waterfall to deter looters. Hatshepsut had reburied his mummy with the water-damaged wrappings in a new tomb from which the 21st Dynasty priests had taken the mummy to his final resting place—the DB320 Cache. This tomb, hopefully with Thutmose II’s funerary paraphernalia intact, remains, inter alia, Pierce Litherland’s dream!

Life and Reign of Thutmose II

One can reasonably say, at the hand of our current knowledge, that Thutmose II’s greatest claim to fame is as the husband of Hatshepsut and the father of arguably the most significant warrior pharaoh of ancient Egypt!

Thutmose II’s dates of birth and death, as well as the length of his reign, remain a matter of uncertainty among scholars. His reign could be any number of years between 3 and 13 (or maybe 14) years. It is generally given as 1493 to 1479 BCE in scholarly writings.

In line with ancient Egyptian royal custom, Thutmose II had five names: Horus name, Nebty name, Golden Falcon name, Prenomen, and Nomen. These were respectively Kanakht Weserpehti, Netjernisyt, Sekhemkheperu, Aakheperenre, and Thutmose or Seneferkhau. A scarab in the Petrie Museum, UK, is inscribed with his prenomen Aakheperenre.

Thutmose II’s armies put down revolts in Nubia. They were also successful in overcoming rebellions in the Levant, which included Syria, Palestine, and Israel. A group of Bedouin rebelled in the Sinai Peninsula during his reign, which the Egyptian armies successfully crushed. These successful military expeditions were most probably achieved without the physical presence of the king, but he, nevertheless, received the credit for them in Egyptian records.

These campaigns are mentioned as though the king was present by an illustrious Egyptian official, Ahmose-Pennechbet, who served in several high offices under five pharaohs of the 18th Dynasty. It is part of this official’s autobiography written on his tomb walls as translated and published by Egyptologist James Henry Breasted (Ancient Records of Egypt Volume II, 1906).

Another tomb autobiography by a royal architect and scribe, Ineni, describes Thutmose II as the good god who vanquished the Asiatics. But he adds a strange rider in the light of what we know from the pharaoh’s emaciated and scarred mummy:

“His Majesty passed a lifetime with good years in peace, went to heaven, united with the sun”(J.H. Breasted, Ancient Records of Egypt, Volume II, 1906)

Ineni’s tomb text, in which he praises Thutmose II and also Hatshepsut several times, was written during Hatshepsut’s reign—another reason why her supposed deliberate destruction of Thutmose II’s name and monuments is questionable. The political climate would surely have made such praise too dangerous, as he was still working for her when the tomb inscription was made.

Building Projects and Monuments

Thutmose II was responsible for a number of building projects, according to Ineni’s biography. A temple at Kumma bears his name on its doorjambs. Unfortunately, the construction of the Aswan Dam may have covered more external inscriptions of Thutmose II outside the temple and on the rock cliffs. According to dedication inscriptions, he was also the builder of the Knum Temple at Elephantine, where he is exalted and praised as the builder.

His typical preference in architectural style is recognized by some scholars, in addition to the Karnak temple. Scholars posit that two statues of Thutmose II sculpted during his reign and positioned at Karnak were repaired and moved to another position by Thutmose III. A dedication to Thutmose II is still visible on the base of one. Blocks of the pillars of Thutmose II’s beautiful open festival court at Karnak were found by archaeologists to have been repurposed by Amenhotep III.

There is substantial evidence that Amenhotep III was the pharaoh mainly responsible for the destruction, defacing, and reusing of Hatshepsut’s statues and building materials. He was also not of the direct royal bloodline (both parents from the main royal house) and may have tried to distract the Egyptian elite and commoners from the last direct link, Hatshepsut. There is little doubt that a damnatio memoriae (condemnation of memory) started late in Thutmose III’s reign, which may indicate the involvement of Thutmose’s son and heir, Amenhotep II. Why else would Thutmose III have waited more than 20 years after her death if resentment and revenge against Hatshepsut drove the act?