The accomplishments of Amenhotep III are often overlooked among 18th Dynasty Egyptian pharaohs. He didn’t conquer new territories like his great-grandfather, nor did he begin heretical reforms like his son. He also never left behind a king’s ransom of riches like his grandson. Instead, his peaceful reign helped secure Egypt’s position in the ancient world. Art became more important than ever, while culture and religion reformed and flourished under his guiding hand. Many of his building projects, such as the Temple at Luxor and the Colossi of Memnon, are representative of ancient Egypt as a whole.

Here, we will look at his key achievements.

Amenhotep III’s Golden Age

Amenhotep III had the privilege of inheriting the rule of Egypt at its peak. With more territory than ever before, more wealth than anyone could imagine, and no wars to fight, Amenhotep III could entertain other pursuits. During his 37-year reign, he continued the efforts of those who came before him. He inspired surface-level religious reform, placing himself, and all pharaohs to come, firmly in the role of the divine. He married several princesses from neighboring kingdoms, fostered diplomatic relations, and avoided conflict where he could.

Art and culture blossomed during his peaceful reign. His festivals were some of the grandest seen during this period and his building projects were some of the largest. His many statues featured such striking and unique features that he is instantly recognizable — even where his statues have been usurped and re-inscribed. Amenhotep III didn’t have to earn his “Golden Age” but his actions helped to maintain everything his forebears had worked for.

The Influence of Thutmose III

By all accounts, Amenhotep III’s rule was peaceful and prosperous because of the work of his great-grandfather, Thutmose III. Thutmose III ruled for a period of nearly 54 years (1479 – 1425 BCE). These years were marred by constant conquest and warfare. Thutmose III led so many military campaigns during his reign that he is often referred to as the ‘Napoleon of Egypt’.

His ambition shaped Egypt in the years to come. Through his military cunning, Egypt secured territory in Nubia, Mitanni, Syria, and Turkey, among other places. While other pharaohs boasted of great military prowess, Thutmose III’s accomplishments were easy to observe in Egypt’s wealthy and growing empire.

Though Amenhotep III became a pharaoh nearly 40 years after Thutmose III’s death, every one of his great-grandfather’s successes contributed to his peaceful and prosperous rule. Still, it took work to maintain those relationships and he continued to establish Egypt’s position in the ancient world. Records of his work can be found in the Amarna Letters.

The Amarna Letters

Most of our information about Amenhotep’s trade relations and diplomatic marriages comes from the Amarna Letters. These clay tablets were excavated from Amarna, the capital established by Amenhotep’s revolutionary son Akhenaten. Their discovery in 1887 shed light on the rich relationship Egyptian pharaohs had with foreign powers. In all, 382 tablets were discovered at Amarna. The bulk of these tablets represent letters that were received from foreign powers. Of particular interest is the correspondence between Amenhotep III and King Kadashman-Enlil I of Babylonia. These tablets discuss the details of diplomatic marriages between the two rulers.

The Egyptian Pharaoh’s Diplomatic Marriages

During the “golden age” of Amenhotep III, being married to an Egyptian pharaoh provided vast benefits. The bride herself was well cared for in the pharaoh’s house and her father benefitted from having a close relationship with the most powerful figure in the region. Amenhotep III’s chief wife, Tiye, was married to the would-be pharaoh at a young age. He would take another Egyptian wife, Sitamun, as well.

In a 2005 chronological dictionary of Egypt’s queens, Wolfram Grajetzki lists the following foreign wives of Amenhotep III:

- Tadukhepa, daughter of King Tushratta of Mitanni

- A daughter of King Kurigalzu of Babylon

- Gilukhipa, daughter of King Shuttarna of Naharin

- An unnamed Syrian princess

- An unnamed princess from Arwaza

- A daughter of King Kadashman-Enlil of Babylon

This list may not be complete, but it does give us context for Amenhotep III’s diplomatic ties. We can see that he took wives from every corner of his vast empire. Through the inclusion of two Babylonian princesses (and two from the Mitanni region), we can see that he married new princesses each time there was a new ruler. This wasn’t necessarily new for an Egyptian Pharaoh, however, the variety of his wives is important to note.

In the various correspondences from King Kadashman-Enlil to Amenhotep III, we see some animosity. Amenhotep refused to send one of his daughters to marry Kadashman-Enlil, stating that “the daughter of an Egyptian King has not been given in marriage to anyone.” This is an important illustration of the power Amenhotep III held in diplomatic affairs. Regardless of how rude this may seem (considering that he’d married both Kadashman-Enlil’s sister and daughter), he refused to stoop so low as to prostrate himself before this foreign king.

It’s important to note that we only have the letters received from this conversation. However, Kadashman-Enlil does a good job of mentioning exactly what Amenhotep III said in the letter he is directly responding to.

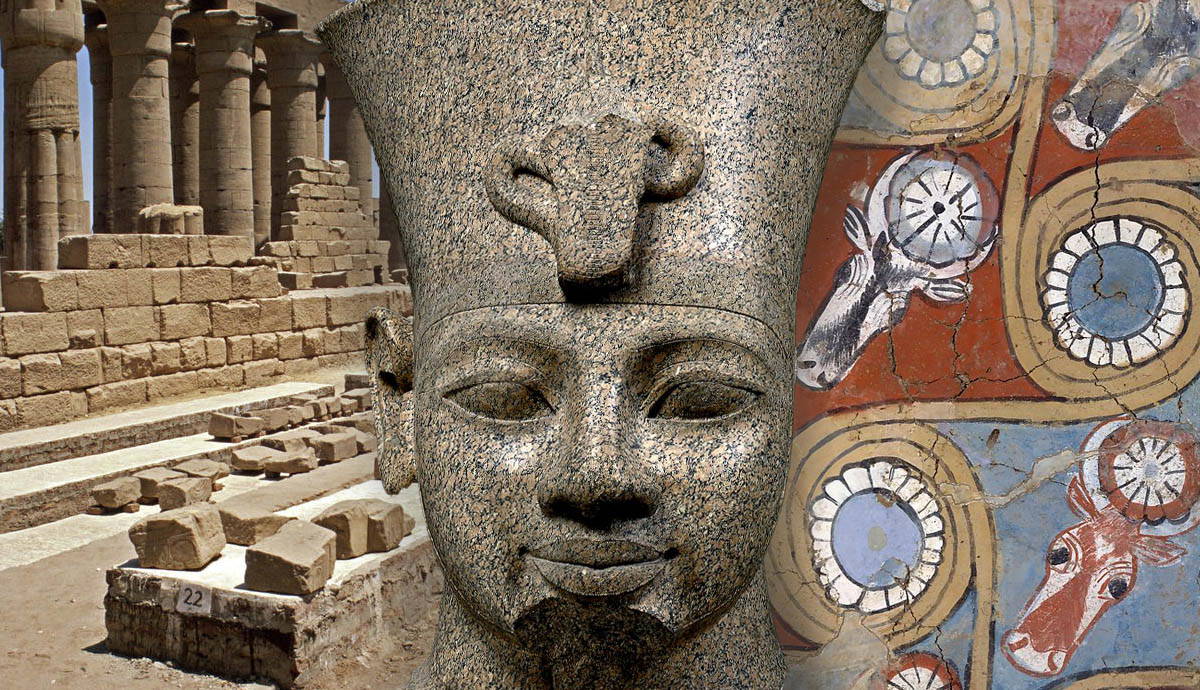

Amenhotep III’s Art Styles

Amenhotep III is instantly recognizable from the statues and reliefs that depict him. His high brows, slanted, almond-shaped eyes and full, feminine lips are iconic. He also happens to be one of the most well-represented pharaohs when it comes to reliefs and statuary. His look was so prolific that later pharaohs would appropriate his statues, re-inscribing them with their names.

This is especially true of Ramses II and Merneptah. We can see many pieces in the British Museum that have been identified as “usurped” by these pharaohs. It’s easy to tell when a statue was meant to represent Amenhotep III due to these distinctive features. When it came to art, this pharaoh’s reign was supreme. The luxury and peace afforded by the work of Thutmose III and previous pharaohs created a booming rise in art during this time.

Special emphasis is placed on the double eyelid line of his statues. This was a trend popular among Asiatic art styles at the time. The slanted, elongated shape of his eyes is often attributed to the same. But his statues were not his only feats. As we’ll examine, his buildings, temples, and reliefs have a great deal to tell us.

The Temple at Luxor

The Temple complex on the east bank of the Nile river was one of Amenhotep III’s greatest building achievements. Though other pharaohs contributed to and finished the building, Amenhotep III began the project. His main achievement within the temple complex was the Colonnade. The columns here were the largest attempted at the time.

Though Amenhotep III didn’t inspire heavy religious reform as his son would, he did bring the mythology of pharaoh’s “divine birth” to center stage. Deep within the Temple at Luxor, he immortalized himself as the son of Amun in a series of inscriptions and reliefs. Hatshepsut, an earlier 18th Dynasty pharaoh, had created similar depictions of this event for her memorial temple.

The “divine birth” of the pharaoh was accepted in mythology. Amenhotep III’s dedication to depicting it so brazenly was almost bold. He thought highly of himself and his role as the divine pharaoh. The Temple at Luxor grew exponentially after Amenhotep III’s rule. Later pharaohs would add to his designs, slowly making them their own. The temple still stands as a tourist attraction that probably sees as much worship now as it did when it was the religious center of Luxor.

The Colossi of Memnon

The giant, magnificent statues of the Colossi of Memnon are synonymous with ancient Egypt. Though they were reclaimed by many rulers afterward and extensively damaged by the Nile River, they are still standing. These statues were created to represent Amenhotep III. They flank the causeway leading to his mortuary temple — or where his mortuary temple used to stand.

This temple, meant to honor Amenhotep III’s life and accomplishments, was destroyed during the 19th Dynasty. Floods from the Nile River eventually wore the temple down and not much of it remains. When it was built, however, it was said to be the largest mortuary temple constructed.

Extravagant Cultural Displays

Amenhotep III’s Malkata Palace was his home. This important structure was the site of his first two Sed or jubilee festivals, in the 30th and 34th years of his reign. Of the three Sed-festivals he held in his honor, these two are the most notable because the site where they were held survived. Sed-festivals were mired in tradition and were extremely important to pharaohs and the people. However, the Sed-festivals of Amenhotep III were at once traditional and extravagant.

New additions to the festival included a water ceremony and a large artificial basin for it to take place in. An account of one festival survives in the tomb of an important official, Kheruef. He states that while Amenhotep III followed tradition in his rites, no one had celebrated in such a grandiose way before. The site of the third Sed-festival did not survive the sands of time. We can only assume that Amenhotep III took his celebration to even greater heights.

Amenhotep III’s Legacy

Unfortunately, Amenhotep III’s thriving Egypt wasn’t meant to last. His drive to change the religious landscape of his kingdom would lead to decline. Essentially, Akhenaten’s rule left a mess that his successors would have to clean up. King Tutankhamun, possibly the most famous Egyptian pharaoh to date, would go to great lengths to undo the changes that his father had made. Afterward, the throne would pass to several advisors and military leaders.

Amenhotep’s death was the beginning of the end for one of the most successful and dramatic dynasties in Egyptian history. However, many of the icons of his rule still exist today. The Temple at Luxor, the Colossi of Memnon, and Malkata Palace are just some entries on the lengthy list of his projects and achievements.