If you think about philosophy, it is probable that many Western thinkers come to mind. Plato, Descartes, Kant; all are native to countries on the European continent. What is often overlooked, however, are the philosophical traditions on other continents that have been unfolding over hundreds—if not thousands—of years. The philosophy of Ubuntu is one of those traditions. Originating in the Bantu and Xhosa people of Southern Africa and popularized by Desmond Tutu and Nelson Mandela, the Ubuntu philosophy embodies a communal ethos that emphasizes shared responsibility, trust in each other, and interconnectedness among the community.

It’s In the Name: The Etymology and Oral Tradition of Ubuntu Philosophy

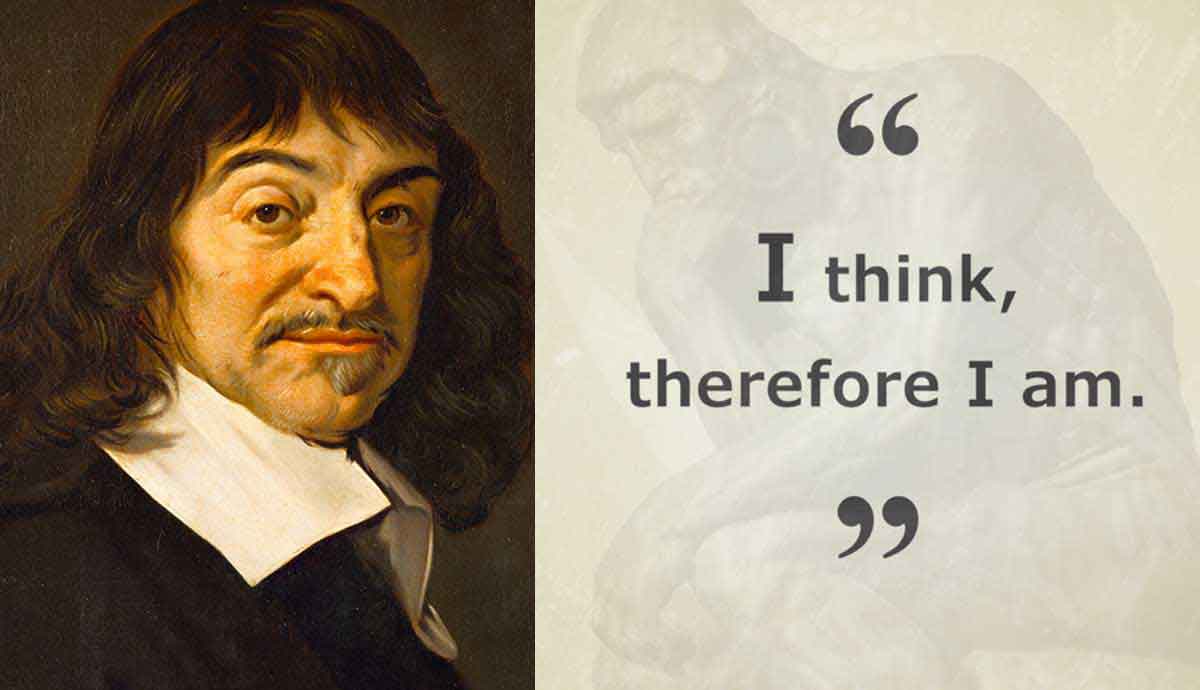

Ubuntu moves away from the Cartesian quote ‘I think, therefore I am’, which takes the individual as a source of knowledge. Rather, the proverb umuntu ngumuntu ngabantu is central to Ubuntu, translating to ‘a person is a person through other persons’. The source of knowledge is, therefore, the community, not the individual. Therefore, we could say that for Ubuntu, ‘I am because we are’.

If we take a look at the name ‘Ubuntu’ itself, we can identify two syllables: ‘ubu’ and ‘-ntu’. ‘Ubu’, in Nguni Bantu languages, refers to the social nature of humans, underscoring the idea that individuals are interconnected: they share a common humanity. On the other hand, ‘-ntu’ refers to the uniqueness of every individual.

If we understand the syllables and their meaning, it is not hard to work out the central idea of Ubuntu: a thorough recognition of the interconnectedness of human beings while acknowledging the inherent worth of every individual. All persons have something to offer, and not one expertise in life should prevail over the other.

The Value of Words and Beyond: Ubuntu Proverbs

The intellectual meaning of Ubuntu philosophy is encapsulated in central proverbs, like umuntu ngumuntu ngabantu. Through oral tradition, these proverbs and phrases get passed on, continuously educating new generations on the values of Ubuntu. While just these words and phrases don’t tell the full story, they do teach us some fundamental basics of the philosophy.

Take, for example, ‘ballaan fira qabu ila qaba’, which roughly translates to ‘a blind person who has relatives can see.’ Or ‘kujikama, uryengi kanthu ndi wala, kusoka uwengi waka’, which roughly translates to ‘kneeling, you eat with elders; keep standing, you eat nothing.’ On closer inspection, we can see that both proverbs have some implied value statements.

The first one indicates the role of the community in generating a sense of self and a sense of belonging. By being connected to your community, the Bantu philosophy teaches us to trust your community members so that you are aware of the consequences of your actions—be it in relation to the community or to nature.

The second proverb indicates the importance of sharing a meal together and showing respect while doing it. While eating is a necessity, the proverb that translates to ‘kneeling, you eat with elders; keep standing, you eat nothing’ indicates that ‘eating’ in itself has little value. It’s only when you sit down and eat with your elders that the meal has an intrinsic, holistic, and moral value to it: it gives you an opportunity to learn from their wisdom.

The proverbs indicate a certain form of embodied knowledge. This is helped by the fact that the Bantu languages are more sophisticated than the English language. This allows for expressing more profound statements when compared to English expressions. The knowledge encapsulated in proverbs is passed on from generation to generation through oral tradition, even teaching people outside Africa about the cornerstones of Ubuntu. However, Ubuntu can only be really understood through its practical application.

Living is the Only Way Toward Understanding

While understanding the meaning of some proverbs is valuable as an introduction, the philosophy exceeds the mere words and phrases that are common in the oral tradition. As anyone remotely acquainted with the overall idea of philosophy, this might seem a bit strange. After all, statues like ‘the Thinker’ or the metaphorical image of the ‘armchair philosopher’ resemble the projection that most people have about people who practice philosophy. In other words, in the academic tradition, philosophy often restricts itself to the theoretical and hypothetical realm. However, different geographical spaces bring different worldviews, and Ubuntu does not exist without its practical application.

The only way to comprehend the interpersonal dynamics you have with others is through living. In turn, this allows the development of a sense of self and belonging, as one starts understanding their unique worth in relation to the community. Additionally, it allows the person to understand the cultural context one finds themselves in, as well as the impact of one’s behavior on the collective well-being of the community. Because of this, every member of the community can flourish in their own way while being thoroughly respected for their uniqueness by the community members.

How Conflict Resolution Exemplifies Ubuntu Philosophy

The most tangible example of why Ubuntu philosophy can only be understood through living comes from conflict resolution. Conflict resolution is applied to either local problems that involve theft or other forms of criminality, or to grander structural problems like the consequences of colonialism and apartheid. Both approaches are rooted in actively gathering with members of the community and restoring relationships.

In the instance of theft or other forms of criminality, the community can get together and reflect on the implications of the crime for the wider communities or affected individuals. The traditional jurisprudence of Ubuntu revolves around the concept of unhu, which acknowledges that crimes committed by one individual have far going consequences, exceeding the offender and the affected persons involved. Through dialogue and trust, a ‘punishment’ is formulated.

However, one might wonder if this is an actual punishment in the true sense of the word. Rather, the focus is on healing the relationship between the offender and the community. Dialogue, apology, and education are central, as opposed to giving the offender a fine or a jail sentence. From an Ubuntu perspective, one might indeed wonder what the value of incarceration is if the relationship with the community is never restored. For if it’s never restored, it will certainly happen again.

On the grander and more structural level relating to the consequences of colonialism and apartheid, Ubuntu offers similar healing processes. To address historical injustices, promote reconciliation, and manifest social cohesion, collective healing ceremonies and memorial services are essential. These allow the community to accept past violations, recognize the consequences for the present, and create a just path forward for the future.

The focus is on the spiritual essence of the community members, which is deemed the highest value of a person: it is considered essential for the expression of character. The bad spirits—in this case, the ongoing consequences of apartheid and colonialism—are to be ‘killed’ with kindness. Through the communal process of recognition and healing, the dreadful past can be ‘killed’ and replaced with contemporary values like inclusivity and trust—which are defined by the characters in the community.

How a Community Can Be More Than Living People

The role of spirituality in Ubuntu is already evident from the conflict resolution mechanisms we just mentioned. Still, spiritual importance goes beyond conflict resolution. It also has implications for what is perceived to be the community. In order to understand the foundational role of spirituality in relation to the community, we need to understand what spirituality in Ubuntu encompasses. Mayer and Wallach define this as follows:

Spirituality is the habit of being oriented towards and motivated by a reality

beyond the immediate needs and wants of our ego. This habit stems from

some kind of immediate experience of reality. Experience means that an

insight is holistic, comprising cognition, emotion, and motivation or behavior.

So really, spirituality in Ubuntu doesn’t implicate a ‘higher spirit’ that informs every action and move of people. Rather, it focuses on all the experiences taking place in the earthly realm; simultaneously affirming the idea that Ubuntu needs to be lived in order to be understood properly. Through living and spiritual health, one starts to gain an understanding about every relationship that is fundamental for the life of the individual.

Because of this holistic approach, the recognition of community is allowed to go beyond the living humans that are part of a community. It means that the individual understands that all influences form their current being. Beyond people living and dead, what influences and forms the individual? According to Ubuntu, the community consists of all living beings in the natural world, the relations between humans and other living beings, but also the cosmos, social events, and the ancestors.

The ‘Be’ Before ‘Being’ in Ubuntu Philosophy

How should we understand the idea that deceased ancestors and nature are part of the community? It mostly has to do with respecting what previous generations and the natural world have already built for you. The living individual that lives according to Ubuntu principles will acknowledge that many beings have shaped—and will continue to shape—the reality that one is born into. After all, the fertile ground in your garden or the house that you’re living in from childbirth onwards didn’t pop up the moment you were born. Just like the community, they were there already; something that should be thoroughly acknowledged and respected. Your ancestors and the natural world created the environment for you ‘to be.’ By acknowledging your foundation, you can now start ‘being’ the person you are.