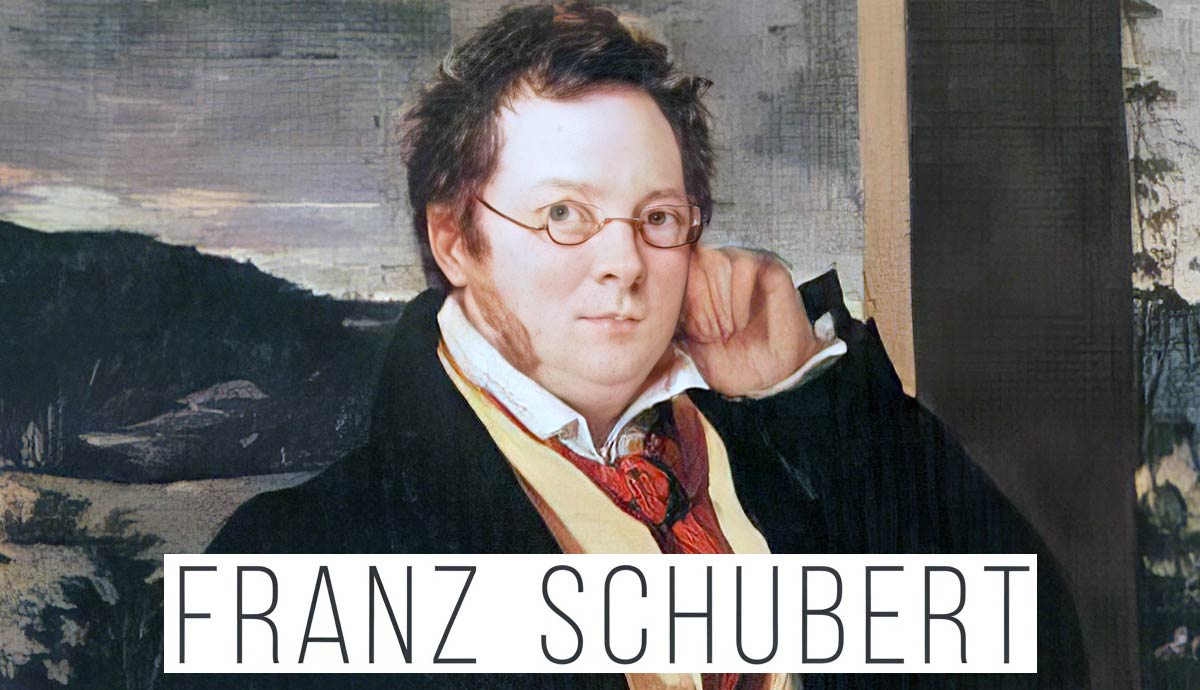

While Franz Schubert never lived a life of financial luxury, his contribution to music is beyond that of riches. He frequently depended on friends for lodging and patronage. During his short 31 years on Earth, he composed nearly 600 Lieder among many other compositions. Yet, publishers were not clamoring to publish his works because he broke away from the established norms of the Classical Era. Come along and discover five works of art that are at times autobiographical and at times pure magic that look to the future.

1. Erlkönig, D. 328

Schubert made a setting of a Goethe poem and drops the listener in medias res. The poem tells the story of a father holding his sick child in his arms while racing home on horseback. The supernatural creature torments the boy, the Erl-King, who lingers in the woods and lures children to their death if they stay in the woods too long.

Although the work is written for a single singer, they are tasked with portraying four distinct personalities. The narrator sets the mood during the opening, asking rhetorically, who is traveling through the night and the wind on horseback. At the end of the Lied, the narrator relays the boy’s fate.

The father sings comfortingly to pacify his sick child. When the boy says he saw the Erl-King, the father brushes it off as his imagination playing tricks on him. The father puts it down to a wisp of fog, wind rustling in the leaves, or an old willow gleaming gray, respectively.

The Erl-King starts as sweet and beguiling, promising the boy games, his daughters fawning over him, and his mother, who has many fine things. As the song progresses, the Erl-King becomes more forceful and threatens to use force to snatch the boy.

As the Lied progresses, the boy becomes increasingly agitated, and his pitch rises with every iteration. Finally, he complains that Erl-King has finally snatched him away.

The piano part also adds to the dramatic nature of the song—the piano’s right-hand part is relentless triplets symbolizing the horse’s hooves carrying the pair home, while a sinister upward run is found in the left hand. When the boy’s fate is revealed by the narrator, the piano accompaniment comes to an abrupt end, symbolizing the end of the journey and the boy’s passing.

2. Piano Quintet in A major, D. 667 “The Trout”

Like Beethoven, whom Schubert respected, the Trout Quintet was born while visiting the countryside (like Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony). While traveling with his patron and friend, Johann Vogl, in the northern parts of Austria, Sylvester Paumgartner, an amateur cellist and wealthy patron, challenged Schubert. The challenge was twofold: Schubert had to incorporate his Lied, Die Forelle, D550 Op. 32 and the same instrumentation Hummel used in his Piano Quintet, Op. 85. It was one of Paumgartner’s favorite works, along with Schubert’s art song The Trout. The instrumentation differed from a standard piano quintet, which is traditionally scored for a piano and string quartet (two violins, viola, and violoncello). Hummel and Schubert’s instrumentation is for a piano, violin, viola, violoncello, and double bass.

Schubert’s musical style had matured by this time, and he rose to the occasion by composing a boisterous five-movement work. He kept with the Classical tradition of a four-movement sonata form composition, but Schubert added a set of themes and variations after the third movement. Thus, he keeps and breaks tradition by creating a five-movement work. Those interested in a musical theory analysis of the work are welcome to watch Mekel Rogers’ analysis here—only a brief overview will be presented below.

Throughout the work, melody reigns supreme, but there is never a jumble of ideas competing for the listener’s attention. The Trout Quintet opens (at 00:07) with a dramatic upward surge echoing the “Trout” theme from his song, Die Forelle, throughout.

A second, slightly slower movement marked Andantino (at 09:17) presents the first theme in octaves in the piano while the viola and violoncello murmur in the background, and the piano takes center stage. The violin and double bass fulfill the role of accompanying the other two-stringed instruments’ soft “conversation.” It forms two symmetrical parts, with the first in a major key signature. The second part, or recapitulation (at 12:31), opens again with the opening material but takes a meandering journey to minor key signature territory. After many modulations, the movement ends in the same key signature as the opening.

Following the Classical tradition, Schubert uses a Scherzo and Trio form in the third movement (starting at 16:07). The two scherzos are in a quick tempo when compared to the slower middle Trio. During the Scherzos, brisk tempos and frequent tempo changes remind one of country folk dances.

The fourth movement is composed in a theme and variations form and features Schubert’s famous song Die Forelle. Each of the five instruments gets a turn to state the theme in a varied form as the movement progresses.

Below is a breakdown of the theme and six variations. Timestamps below refer to the video analysis above:

- At first, the theme is plainly stated by the string instruments (at 19:43) without embellishments.

- In the first variation (at 20:45), the piano takes center stage with trills symbolizing the trout’s maneuvers through the water. The strings play the water motif that sounds like a babbling stream.

- For the second variation (21:39), a duet is played by the viola and violoncello. The viola is tasked with long, free-flowing phrases that vary the original theme.

- In the third movement, the theme slides down further in pitch to the violoncello and double bass duet (22:37) while the piano provides a brisk accompaniment along with the other strings.

- Things take a dramatic turn during the fourth variation (23:24) and shift to a minor key signature. The piano and strings are caught up in a call-and-response pattern alternating between minor and major key signatures.

- In the penultimate variation (24:25), the violoncello plays the original theme in dotted rhythms, causing the theme’s notes to sound a bit “wobbly” because a longer note is followed by a shorter one. These dotted rhythms create the idea of a stream flowing over rocks before reaching the final destination.

- A series of duets (at 26:01) reintroduces the theme before the whole quintet (26:52) rejoins and the movement comes to a close. Finally, Schubert’s trout has reached its destination.

The final movement, marked Allegro (lively), features the triplet rhythms (three notes in the time of one) from the opening movement. Through the triplet rhythms, the music gains a bouncy character emulating the trout’s movements as it makes its way through the stream. Contrasting dynamics and articulations further give the music a flowing character, emulating a stream slowing down and speeding up as it travels through the landscape.

Overall, the quintet’s mood is light and cheery and showcases Schubert’s mastery and developing themes and melodies. The addition of the double bass grounds the piece and provides nuance and depth. The Trout Quintet has endured as a favorite chamber music piece among concertgoers and musicians alike.

3. Symphony No. 9 in C Major, D. 944 “The Great”

Unlike Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, which was composed towards the end of his life, this is not the case with Schubert’s final symphony. Schubert composed the symphony between 1824 and 1826, with the bulk of the composing taking place during 1825. By the spring or summer of 1826, Schubert finished the orchestration. Unfortunately, Schubert was unable to pay for a performance and rather dedicated it to Vienna’s Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde (Society of Friends of Music), who would perform the work. They responded by sending him a small sum of money. The Society copied the parts and performed a run-through later in 1827. Regrettably, the Society decided that the work was too technically demanding and too long for the conservatory’s amateur orchestra to perform.

Schubert followed in Beethoven’s footsteps by using the same compositional techniques as the master he revered but never dared to meet face-to-face. Beethoven, in turn, built upon ideas handed down by Haydn and Mozart but gave those ideas freer expression. Schubert uses Beethoven’s ideas, which are already looking to the future and the Romantic Era.

A brave horn solo opens the work, which is later taken up by the entire orchestra and developed further. The movement is composed in a Classical sonata form but with a Beethovenian twist. Melodies are introduced early in the work during the exposition, undergo fragmentary development, and are later restated during the recapitulation.

In the second movement, the low strings offer a brief introduction before the oboe opens with a gentle, march-like principal theme in a minor, which is quickly taken up by the strings. The second theme is stated in F major and sounds more sonorous and consoling. Interestingly, Schubert does not include a development section as would have been the Classical tradition. During the recapitulation, the first and second themes are extended and developed into musical ideas as if they were a development section at the end of a sonata form instead of before the recapitulation. Of further interest is how Schubert emulates Beethoven’s use of the assertive brass and string passages against plaintive woodwinds in the second movement of his Symphony No. 5, Op. 61 No. 1.

Again, Schubert looks to Beethoven for inspiration in the third movement. This time, he uses the master’s decided contrasts between the Scherzo and Trio as evinced in his symphonies.

In Schubert’s third movement, the Scherzo sections (at 29:30 and 36:32) are brimming with excitement, opened by the brass section and low strings. The woodwinds and upper strings (first and second violins and violas) provide some high-pitched excitement. Short bridge passages on repeated notes link the first Scherzo to the Trio and finally lead the music back to the second Scherzo.

During the Trio, the mood calms down dramatically, and a flowing melody (between 33:27 and 36:30)—reminiscent of a Ländler country dance. Finally, the Trio sweeps in again for its grand finale (at 36:32).

In the last movement, Schubert uses an extended sonata form—six unique thematic units can be found in the movement’s exposition. During the development section, Schubert focuses on the third and sixth themes and changes and develops them further. Instead of returning to the tonic (home key signature), Schubert takes a meandering road to lead there in the end.

Overall, the last movement is filled to the brim with energy and shows Schubert’s mastery of the Classical era symphony while looking toward the future, along with Beethoven. But unlike Beethoven, Schubert does not use long introductions or codas to begin and end his works. There is a compactness within the symphony that at once makes it large yet economical and digestible.

4. Die Winterreise, D. 911

Schubert composed this cycle in two parts during 1827—the first in February 1827 and the second in October 1827. There are 24 Lieder in the cycle, divided into two parts of twelve each. We could argue that the work has a semi-autobiographical quality too, which will become clear in a moment.

Schubert became ill towards the end of 1822 due to contracting syphilis. The illness would take its toll during his life—his mental and physical health would suffer, and this was reflected in the music he composed, too. As he was working on Die Winterreise (The Winter Journey), he was dying too. The winter journey may be seen as a symbol of Schubert’s journey alone towards his death. Perhaps he took a stoic approach, contemplating his death as he penned the music, or maybe he was reminded that we will all eventually die, as memento mori artworks constantly remind us.

The set of songs (called a cycle) is somewhat like a monodrama with the singer portraying the principal role. The main character’s beloved has chosen another above him, and he leaves town in desolate grief (Gute Nacht). He journeys through the winter landscape, reminiscing (and berating himself at times) about love and life. As he journeys, he takes time to rest in a charcoal burner’s hut (Rast, i.e., rest) before continuing through a village (Im Dorf, the Village) and past a crossroads. He contemplates death (Das Wirtshaus, or The Inn) but realizes that all the “beds” are already occupied and continues his journey. Overcome with grief, he renounces his faith.

The last song, Der Leiermann (The Hurdy-Gurdy Man), is the only one that features another character—a mysterious street musician. The final lines of the Lied, “Strange old man. Shall I come with you? Will you play your hurdy-gurdy to accompany my songs?” add to the overall enigmatic tone throughout the cycle. It is unclear what the protagonist’s fate is; perhaps the street musician was Death himself waiting for him. Maybe it is only a street musician who begs to stay alive. Or, perhaps, it is Death itself playing a danse macabre, and the lonely wanderer will finally succumb to the death he desires throughout the cycle.

The cycle could also be interpreted from a philosophical stance, and for this, we can turn to Arthur Schopenhauer for some “inspiration.” Although life is filled with suffering, according to Schopenhauer, the arts offer some respite from it all through aesthetic contemplation. By immersing ourselves in art, we can momentarily cast off life’s chains and experience peace and objectivity. Eventually, we have to return to life, but we have the memory of the enjoyment to savor and carry us through the darker times.

5. Four Impromptus, D935, Op. Posth. 142

The two sets of impromptus were composed between the two halves of Die Winterreise in 1827. The complex piano writing and lyrical beauty show a combination of directness and intimacy with poetic sensitivity, and a structural control combined with grandeur. These elements form the characteristics of Franz Schubert’s mature compositional style. Such characteristics would inspire and influence later Romantic-era composers across Europe. It also helped shape the development of the short piano piece in the Romantic era as a genre.

Some scholars believe that The Four Impromptus were meant to be a multi-movement sonata because of the structural and thematic connections among the pieces. However, this idea remains a topic of debate among musicologists and researchers.

The impromptus are presented below as if they are a sonata with individual movements—whether or not the listener perceives it that way is up to them.

First, we have an impromptu in F minor with the characteristics of a sonata. Although it sounds like a sonata exposition, an expressive dialogue is heard throughout between the treble and bass, with the middle register providing the accompaniment. During the “recapitulation,” the music is in the uncommon territory of F major before concluding in the tonic, F minor—usually, a sonata’s recapitulation is written in the tonic of the home key signature throughout.

In the second movement of the quasi sonata, Schubert follows the Classical tradition crystallized in the works of Haydn, Mozart, and early Beethoven. The opening is reminiscent of Beethoven’s Piano Sonata in A-flat Major, Opus 26—perhaps it was intended as a homage to the composer Schubert revered deeply. It may also be a coincidence. The overall character is flowing and lyrical until the contrasting middle section breaks through at 03:26. Schubert uses a continuous triplet accompaniment to distinguish the Trio from the Minuet. Finally, the Minuet returns (at 05:52) and brings the impromptu to a close with a calm ending.

Once more, Schubert employs a model set forth by Beethoven, especially in his Diabelli Variations, Op. 120 when composing a theme and variations. The theme is varied by increasing the subdivision of the beat into smaller units, adding ornamentation, and a return to the tonic (original) key signature when the final variation is reached. Just like the Trout Quintet, Schubert uses a brief passage or freely composed music to return to the tonic.

The final impromptu is a showcase for Franz Schubert’s use of unpredictable accents but also rhythmic vitality. This is by far the most technically demanding Impromptu in the set and uses a wide variety of virtuoso keyboard writing, which includes quick passages in thirds, scales running up and down the piano keyboard (sometimes both hands simultaneously), trills, arpeggios, and broken chord passages. The coda is especially demanding with the double octaves in both hands.