In the early twentieth century, Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque revolutionized modern painting by inventing the art movement of Cubism. Cubism relied on intellect rather than on emotions and dissected physical spaces and objects into collections of overlapping flat planes. Cubism combined influences of African sculpture, the painting style of Paul Cezanne, and Picasso’s own explorations. Read on to learn more about Picasso’s Cubism.

The Origins of Picasso’s Cubism: From Science to Cezanne

One factor that greatly contributed to the changing perception of self and the world around was the mind-blowing advancement of science. Einstein’s Theory of Relativity and Neils Bohr’s explorations of the atom reshaped the idea of the physical world, even for those who were far removed from science in their daily and professional lives. Along with the changing perception of the outside world, the inner human self was also revealed from new angles with the development of psychiatry and related fields. Psychoanalysts like Carl Gustav Jung and Sigmund Freud explored both the universally shared aspects of the human psyche, known as the collective unconscious, and the personal ones, shaped by experiences and predispositions.

All these transformations led to the gradual dissatisfaction with the art of the previous centuries. Painting, sculpture, and other mediums have always been intrinsically connected to the era of their creation, reflecting cultural norms, concerns, and basic worldviews. Although the art of the previous centuries remained valuable for its technical and symbolic content, its form did not correspond to modernity, its challenges, and concerns. Little by little, artists began to separate the act of painting from the need for a recognizable rendering of an object. Instead of creating meanings through narratives, they started to experiment with form and color separated from physical objects.

Paul Cezanne was the artist who almost single-handedly transformed the artistic scene. While observing natural scenes and objects, he came to the conclusion that any complex form could be simplified into one or several easy geometric shapes: a circle, a triangle, or a rectangle. Applying this principle to still-lifes and landscapes, he turned paintings into collections of color planes rather than true-to-life depictions. Cezanne’s explorations were among the principal inspirations for Pablo Picasso.

Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque

After Pablo Picasso moved to Paris in 1900 as a young painter, his art followed a succession of artistic periods and stylistic inspirations. Apart from his vast knowledge of Renaissance and Modern European artists, he was profoundly interested in non-Western cultures and art forms.

European colonialism played a decisive role in developing many progressive art movements of the era. By the beginning of the 1900s, French museums and curiosity exhibitions were flooded with artifacts of African origin—ritual masks, sculptures, and material culture objects. Most viewers treated them as anthropological evidence that hinted at their authors’ supposed cultural underdevelopment.

Artists like Picasso, however, save the creative thought behind those forms and the conceptual power of African art. Picasso carefully studied African sculptures and even amassed his own collection of the works. Through his lens, African art was the carrier of pure artistic vision unspoiled by civilization. Although this point of view was certainly much less derogatory, it still followed the colonialist logic of separating the White Western Self from the Black African Other.

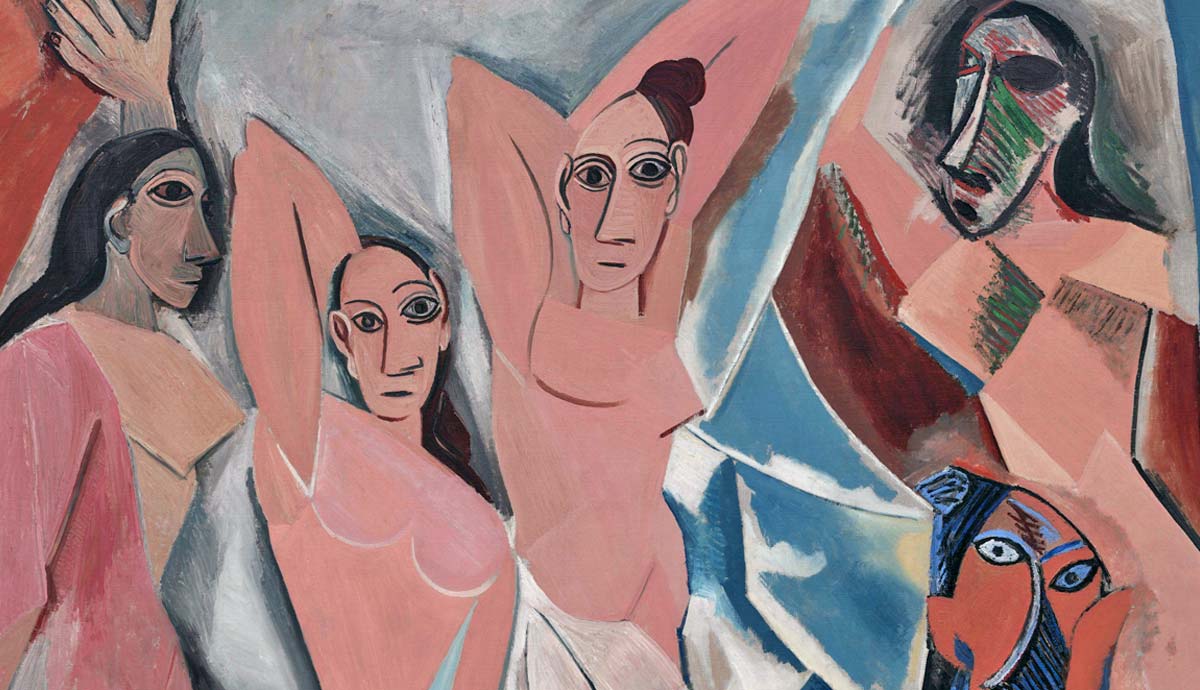

In 1907, a year after Paul Cezanne’s death, the Paris Salon opened a large retrospective of his works. Picasso and a fellow painter, a Fauvist Georges Braque, visited it and were so impressed they soon embarked on their own explorations of modern style, influenced by Cezanne’s geometry and color. Combined with African influences, Picasso’s own technical skill and Cezanne’s conceptual approach brought something entirely new to the artistic scene. Les Demoiselles d’Avignon was the monumental proto-Cubist that dissected physical space into planes.

It represented a scene in the brothel, quite typical for the art of Picasso’s era, yet offered a new way of seeing. Instead of presenting the viewers with yet another idealized female body, he dissected the figures of women into planes and facets, similar to forms seen on wooden African masks. Although Les Demoiselles is considered one of the most influential paintings in modern art today, in 1907, very few of Picasso’s colleagues appreciated it. The backlash was so severe that he decided to keep it in his studio, mastering the courage to exhibit it only nine years later.

Analytical Cubism, 1909-12

Although the first breakthrough work had not yet reached its audience, Picasso and Braque had already begun experimenting further. Instead of relying on the emotional component of painting, they chose to emphasize the intellectual one. To focus on structure and form, they decided to eliminate color—using mostly brown and grey palettes. The first stage of Cubist development was called Analytical due to the intense intellectual labor required to compose a convincing dissection of reality. Each object, whether a human figure or a set of bottles on a cafe table, was carefully transformed into a collection of overlapping planes that represented it from several angles at once. One of the highlights of the era was Pablo Picasso’s painting Ma Jolie. In it, the artist transformed the image of his partner Eva Gouel playing the guitar into a flat plane with triangles and straight lines imitating the musical instrument.

Apart from the obvious stylistic nuances, Cubist painting had one significant feature that set them apart from most other avant-garde movements. It was completely immobile, capturing various planes and states of the painted objects but never demonstrating any form of continuous progression or narrative. For that reason, carefully arranged still-lifes and portraits of models sitting still were the most popular topics for Cubist art.

Nude female figures were also popular, almost always depersonalized into a collection of erotic symbols. In the works of the Analytical phase of Cubism, there was little depth or illusion of space, and light and shadow did not follow natural laws. At the time, Picasso and Braque created works that were almost identical, as they worked closely together and made new discoveries along the way.

Synthetic Cubism, 1912-14

By 1911, Cubist painting became popular among the young artists who tried to learn from Braque and Picasso. However, very few of them were able to truly grasp the conceptual depth of the style. The only artist who was accepted by both founders as their equal was Spanish-born Juan Gris. The new energy brought by Gris into the style contributed to the development of the next stage, Synthetic Cubism. Gris was used to bold and experimental work with color and, little by little, introduced more of it into the monochrome Cubist compositions.

In all its intellectual complexity, early Cubist works essentially looked the same due to the limited color palette and the same set of principles applied. To make the works more visually appealing and bold, Picasso and Braque began experimenting with collage and assemblage. Adding fragments of newspaper, musical sheets, or even three-dimensional objects like chair seats radically transformed Cubist relationships with space. These elements finally bridged the gap between experiencing physical space and transforming it into an artwork.

The assemblage technique revived Cubism and kept it afloat until the beginning of World War I. The conflict that shook the entire world shocked the art world and temporarily halted any progressive avant-garde techniques. For the following decades, art would focus on ways of reinventing itself after a major trauma.

Picasso’s Cubism & Feminist Critique

More than a century later, feminist art historians developed a critical outlook on Cubism. While realizing its creative innovation, they nonetheless highlighted how exploitative and often predatory Picasso’s artwork was. They argue that classical Cubism offered only one perspective, that of a white male artist, who treats women as subject matter on the same level as bottles and apples on their table. It does not help that many of these women were sex workers treated as commodities. The exotic erotism of Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, as well as the depersonalization of those women by masking their faces, clearly demonstrated the space that feminine figures occupied in Picasso’s art.

Still, it is necessary to state that Cubist painters had women among their ranks, although their painting styles were more personalized and sometimes loosely related to the general expectation of Cubism. One of the most famous representatives was Marie Laurencin, known for her soft colors and flowing lines. Another famous Cubist artist was Tamara de Lempicka, who blended Cubist influences with the decorative aesthetics of her teacher, Maurice Denis. These women artists reimagined Cubist art to fit in their perspectives and concerns.