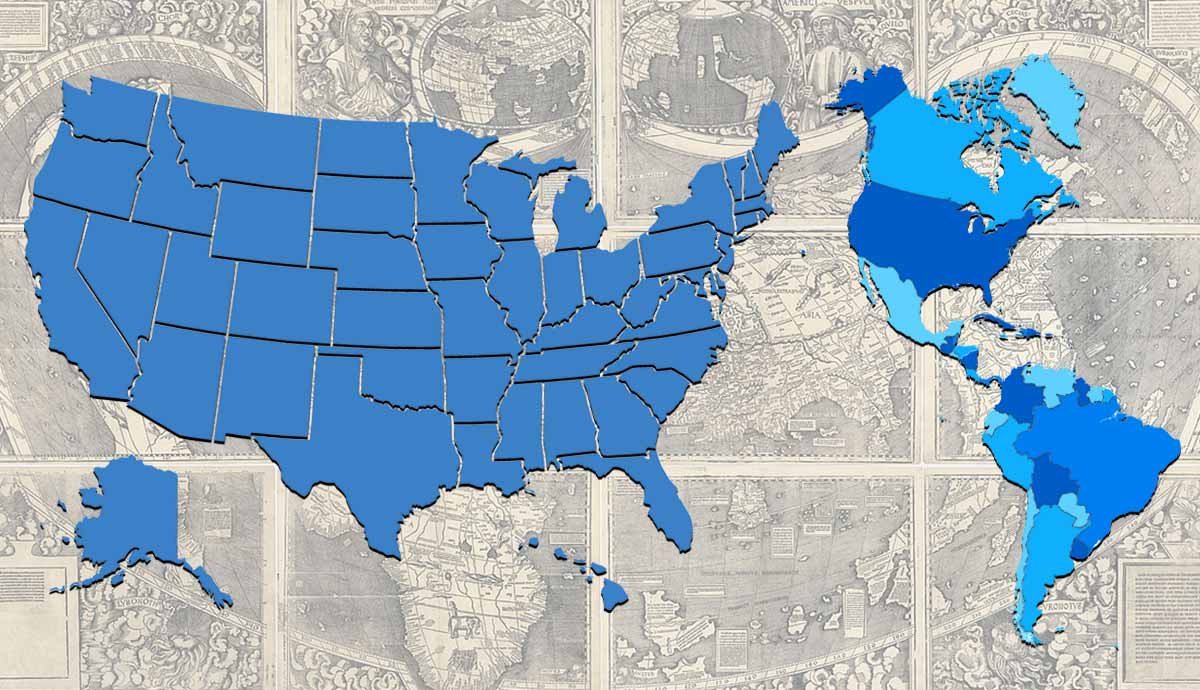

While people from the United States find using the term “America” to refer to their country natural and logical, many outside the country view this usage as discriminatory or imperialist. Some argue that using “America” to refer to the US is correct because it is part of the country’s official name; others believe that “America” should include all the peoples of the American continent. This debate has arisen throughout US history, during which various names were proposed and used to pursue independence and later imperial interests.

Useful Terms

| Term | Meaning in US Context | Meaning in Latin American / Global Context |

| America | The United States (nation-state) | The whole American continent(s) |

| American | Citizen of the United States | Inhabitant of the Americas (North, Central, South) |

| Americanized | Something influenced by the US | In Spanish, defined as “related to the US” |

| US American | Alternative term for US citizen | More precise, sometimes used in academic and cultural debates |

America: A Geographic and Geological Primer

Although the modern understanding of the term “continent” might seem a relatively stable geographical concept, its definition is subject to some debate. From a geographical and geological perspective, continents are continuous masses of land, preferably separated by water and sometimes corresponding to tectonic plates. However, there are different continental models composed of various numbers of continents, which have been developed for specific cultural and historical reasons. For instance, in English-speaking countries, kids are taught that there are seven continents and that America is divided into North America and South America.

Conversely, in Latin American countries as well as European countries where Latin-descendant languages are spoken (e.g., French, Portuguese, Italian, Spanish), a six-continent model is more common. This model considers America a singular extension of mass (ignoring man-made divisions such as the Panama Canal). Moreover, in Latin American countries, the American continent is divided into three subregions: North America, Central America (sometimes including the Caribbean islands), and South America.

This is not only true in the Western hemisphere. Another example of such differing perspectives is seen in models defining Europe and Asia as a single continent (Eurasia) vs. others defining them as separate continents. Moreover, different international entities might use different models; for instance, the Olympic Games use a five-continent model, whereas the United Nations divides countries into six different continental regions.

| Model | Number of Continents | America Defined As | Common Regions Included |

| English-speaking (school model) | 7 | Two separate continents: North America & South America | North America, South America, Europe, Asia, Africa, Australia, Antarctica |

| Latin-speaking countries (e.g., Spanish, Portuguese, French, Italian) | 6 | One single continent: America | America, Europe, Asia, Africa, Oceania, Antarctica |

| Olympic Games model | 5 | One continent: America | America, Europe, Africa, Asia, Oceania |

| UN Statistical Division | 6 regions | America split into North America, Central America/Caribbean, South America | Africa, Americas, Asia, Europe, Oceania, Antarctica |

Returning to the American continent, geologically, it is divided into two sections corresponding to two different geological plates: the North American and South American. This has been identified as one of the reasons the region is taught as a composition of two distinct continents in English-speaking countries. In contrast, from a cultural and historical perspective, the name America was given to the entire continent in the 16th century. The name was popularized in Europe by German cartographer Martin Waldseemüller, who created a world map called Universalis Cosmographia (Universal Cosmography), where he used the word to refer to the “new” lands that Amerigo Vespucci had “discovered” in 1502 (in contrast to Christopher Columbus, who thought that the lands he stumbled upon were part of India or the “West Indies”). Waldseemüller used the feminine variation of the name to continue the tradition of naming continents with female names in Latin-descendant languages: Europa, Asia, or Africa.

This new information about the existence of an unknown continent produced a great “cosmographic shock” in Europe. European geographers took on an important role as they, by drawing new maps, shaped a world divided into sections and created the idea of continents. America was then “invented,” and the world was reorganized not only geographically but also culturally.

History of the Names “America” and “United States of America”

At first glance, the name “United States of America” appears to simply be a literal description: a union of different states in a defined region of the American continent. However, one of the most common terms people in or from this region use to refer to their country is “America.” This begs the question: why do people call this single country “America” if this is also the name given to the entire continent? It is easy to recognize that using “America” to refer to a single country and “American” to refer to only the people who live or were born in the US ignores the 600 million other people living in this same region but outside that one country—who have many different nationalities and cultures.

Contrary to modern usage, the United States was not always recognized as just “America.” The name “United States of America” first appeared in the first draft of the Articles of Confederation on July 8, 1776, and was later formalized in the 1787 Constitution. It replaced the name “United Colonies,” which was how the US was referred to at that time. The phrase “United States of America” was used descriptively to refer to a geographical and political union of different states within the American continent and not as a proper noun, in contrast with other countries in the region after gaining independence, like Mexico or Venezuela. A more recent historical discovery indicates that the phrase “United States of America” was first coined by an anonymous writer in the Virginia Gazettes, a newspaper published in Williamsburg that documented the unfolding of the US Revolution.

In a recent article entitled “When did the US start calling itself “America,” anyway?” Daniel Immerwahr, an associate professor at Northwestern University, explains the historical development of how and why the name “America” gained relevance in the US. After the country was officially named the United States of America, physician and naturalist Samuel Latham Mitchill complained about the struggles of using the name to refer to its nationals: “United States men?” He proposed Fredonia as a more universal term, while poet Philip Freneau proposed Columbia. This last name gained relevance in the republic as a symbolic separation from the British, from whom they had won independence in 1776. Many institutions then adopted the name to historically align with the independence movements that happened between 1770 and 1836 in other countries of the continent, especially Gran Colombia (Great Colombia), which became a political entity independent from Spanish rule in 1810. An example of this political and linguistic shift is how Columbia University changed its name after the US War of Independence in 1787.

Paradoxically, although the US was sympathetic towards the independence and sovereignty of its neighboring countries in the 18th century, by the early 20th century, the US had annexed Hawaii, the Philippines, Puerto Rico, and some Pacific islands after the war against the Spanish in 1898. The political alignment of the US then shifted toward becoming an imperial power, and the process of territorial expansion pushed the country to find a new name that illustrated the union of states and colonies more effectively. The name “America” gained popularity and was first legitimized by Theodore Roosevelt while giving a speech about their victory against the Spanish.

US residents had been called “Americans” since the 18th century when colonists born or settled in what was then the US territories used the word to distinguish themselves from the British. Moreover, the British spread the term widely, calling their enemies “Americans. Throughout the 20th century, the US signed treaties that referred to themselves as “Americans,” consolidating the meaning in the international landscape.

| Proposed Name | Advocate | Reason / Context |

| Fredonia | Samuel Latham Mitchill | Wanted a universal term for US nationals instead of “United States men.” |

| Columbia | Philip Freneau (poet) | Symbolic separation from Britain; gained popularity after independence. |

| Usonia / Usonian | James Law (1903) | To fairly distinguish US citizens from all other inhabitants of the Americas. |

| United States of America | First draft of Articles of Confederation (1776) | Formal descriptive name for union of states. |

Opposing View: Hearing From the Other Americans

The wide use of the word “America” to refer only to the US has greatly influenced different sociopolitical debates. The appropriation of the word has been interpreted by some scholars as an imperialist tendency that nationalizes the name of a continent and excludes many other people from their concept of what “American” means and who “Americans” are. This appropriation extends to the United Nations, where US citizens are often called Americans, and to the Diccionario de la Real Academia Española RAE (Royal Spanish Academy Dictionary), where one of the definitions of Americano is “people from the US” and the definition of Americanizado (Americanized), “becoming something related to the US.” Even in other languages and countries, the words “America” and “American” are associated solely with the US, leaving little room for other spaces and communities also inhabiting the American continent.

However, claims about the misuse of the term “America” to refer to only the US aren’t new; they can be traced back to writer James Law, who in 1903 wrote that the people from the US had no right to use the title “America” to refer solely to themselves, as this was unfair to Canadians and Mexicans. He, in turn, proposed the word “Usonian.” However, it is within the Latin American context that the term “American” has been most widely contested, as it has been identified with historical US interests in imperialist expansion and military and economic intervention in different Latin American and Caribbean countries. Moreover, today, the association of the US with “America” has frequently been used with nationalistic, xenophobic, racist, and anti-immigrant intent: for instance, Ronald Reagan’s motto, later appropriated by Donald Trump, “Make America Great Again,” and right-wing aligned claims such as “Make America One Again” or “America for Americans.”

Some have proposed using “US American” or “United Statian” as possible responses to this conflict. The first concept is more descriptive and refers to the people born in the US. While perhaps it doesn’t roll off the tongue, it is a proper noun found in the Merriam-Webster dictionary as a legitimate way to “refer to a native or inhabitant of the United States.”

If no effort is made to advocate for more accurate and culturally and historically sensitive terms to refer to the people in the US, there will always be confusion over having a term used to refer to both a single country and the entire continent. Furthering this confusion, the US is increasingly becoming a multicultural country that demands the recognition of people migrating from abroad and who, if coming from Canada, Latin America, or the Caribbean islands, could rightfully be considered “Americans” as well.

Bibliography

Lewis, M. W., & Wigen, K. (1997). The myth of continents: A critique of metageography. Univ of California Press.