Imposing and impenetrable, Renaissance palaces were a distinctive urban feature of sixteenth-century Rome. Designed to command respect with their towering façades, these buildings proclaimed the power of the noble families living within them. But hidden away in Trastevere, another kind of Renaissance dwelling appeared, one that departs from the rigid grandeur of those city residences. Commissioned by Agostino Chigi, whose wealth rivaled that of kings and popes, but whose passions lay in art, poetry, and philosophy, Villa Farnesina is not a palace of rulers, but a retreat for delight.

Agostino Chigi: The Vision Behind the Villa Farnesina

Born in Siena in 1466, Agostino Chigi became one of the wealthiest and most influential figures in Renaissance Rome. A banker and merchant, he amassed a vast fortune through savvy investments, monopolies and connections, which included dealings with the papacy and the powerful Medici family. Chigi’s decision to commission a villa was driven by a desire to create a grand residence that reflected his wealth, status, and appreciation for culture in the city of Rome, where he moved in 1487 to work as the banker of Pope Julius II.

Under this pontiff, the city was undergoing a period of intense transformation, meant to enrich the city’s architectural and artistic landscape. In this climate of renewal, Chigi saw the building of a villa as an opportunity to showcase his success and refinement. Villa Farnesina was in fact his stage for the performance of legendary displays of opulence and extravagance. One of the most famous of these performances took place during a banquet in the villa’s gardens, where Chigi, in a spectacular gesture of nonchalance, ordered his servants to throw the villa’s gold and silver plates into the Tiber, only for them to be later retrieved by means of secretly placed nets in the water. Such ostentatious acts reinforced his image as a man of almost mythical wealth, a patron whose riches seemed inexhaustible.

But the villa was also conceived as the embodiment of the patron’s knowledge, intellectual pursuits, and artistic interests. Renowned artists, such as architect Baldassare Peruzzi, Raphael, Sebastiano del Piombo, and Il Sodoma were invited to contribute to its design and decoration. The villa’s central theme, an allegory of love and humanism, was meant to convey Chigi’s sophisticated taste and his devotion to classical ideals, whilst the collaboration of artists was intended to inspire conversation, contemplation, and creative expression, making it a space for artistic exchange as much as for leisure.

Each space within the villa was carefully curated to project an image of Chigi not just as a banker, but as a true Renaissance patron, deeply engaged with art, mythology, and intellectual discourse. The frescoes that adorn the walls and ceilings tell stories of divine love, heroic trials, and celestial beauty, mirroring Chigi’s own desires for power, romance, and immortality through art.

The Loggia of Galatea

The Loggia of Galatea hosts one of the villa’s most celebrated frescoes, reflecting Chigi’s love of beauty, pleasure, and the classical world. Painted by Raphael, this fresco depicts the sea nymph Galatea, surrounded by playful sea creatures, Neiads, and Tritons, riding triumphantly on a shell-driven chariot to escape the clutches of the monstrous cyclops Polyphemus.

The cyclops, however, is found in an adjacent fresco painted by Sebastiano del Piombo, a juxtaposition that creates a visual dialogue between the two artists, deliberately orchestrated by Chigi to foster competition between them. This rivalry between Raphael and del Piombo, the first employing the classical forms and disegno of the Roman school and the second displaying the primacy of colour over line of the Venetian tradition, encapsulated the Renaissance spirit of artistic challenge and innovation.

This room is also one of the most enigmatic and deeply personal spaces in the villa, offering a glimpse into Agostino Chigi’s fascination with astrology and his belief in destiny. The ceiling features an elaborate astrological chart that marks the precise celestial alignment on November 29, 1466—Chigi’s birth date. By dedicating an entire space to the depiction of his birth chart, Chigi transformed the room into a cosmic declaration of his divine favor, suggesting that his immense wealth and power were preordained by the stars. The astrological chart is a striking element of the decoration, given that astrology was often viewed with suspicion by the Church, especially when used to predict fate or challenge divine providence. While in papal palaces and public religious spaces such overt displays of celestial influence would have been inappropriate, within the private sanctuary of a villa such concepts could be explored.

The Loggia of Cupid and Psyche

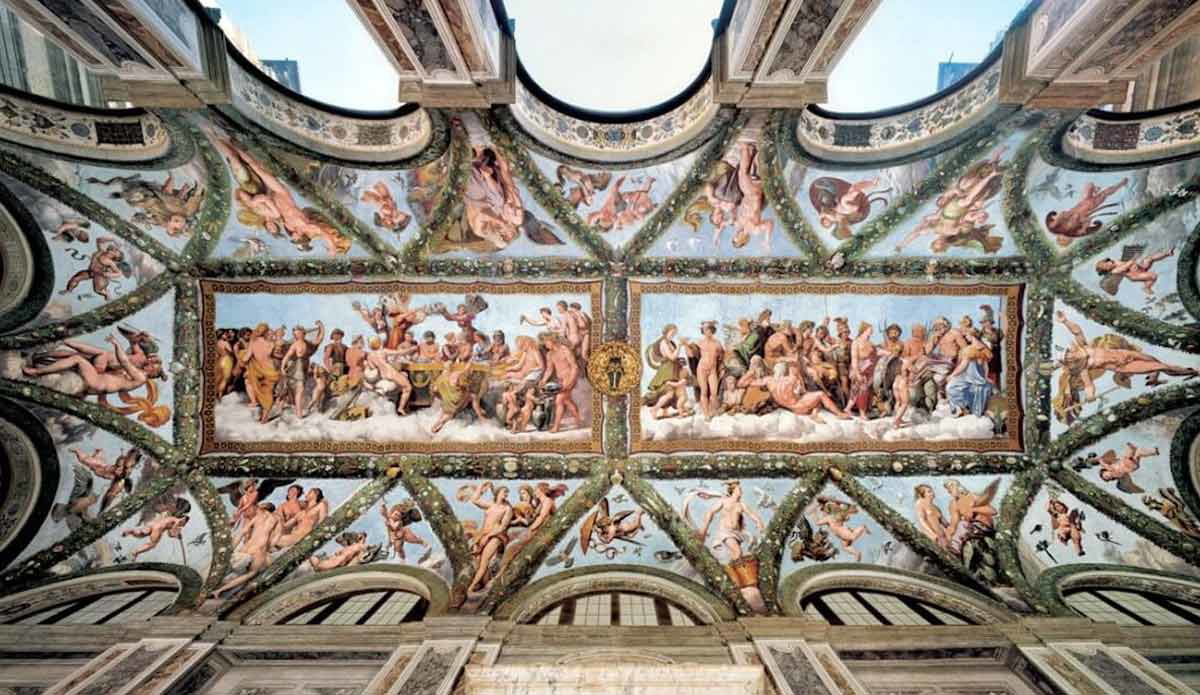

The Loggia of Cupid and Psyche in Villa Farnesina is an apotheosis of illusion and symbolism, seamlessly blending the boundaries between interior and exterior while serving as a grand celebration of love, both mythological and personal. Designed by Raphael and executed by his workshop, the fresco cycle transforms the ceiling into an open-air pergola, where painted garlands of fruits and flowers intertwine with a sky so vividly rendered that it appears to dissolve the ceiling. This trompe-l’œil effect creates an immersive experience, making the loggia feel like an extension of the lush gardens outside, blurring the line between art and nature, reality and fantasy. In doing so, the space becomes an idyllic setting for pleasure and festivity, perfectly in line with Agostino Chigi’s vision of the villa as a retreat from the formalities of power, a place where beauty, myth, and intellect coexisted in harmony.

Beyond its artistic brilliance, the Loggia of Cupid and Psyche carries profound personal significance, as it reflects Chigi’s own love story with Francesca Ordeaschi, the Venetian courtesan whom he would later marry. The frescoes depict the trials and triumphs of Psyche, a mortal who undergoes a series of challenges before being granted immortality and uniting with Cupid in divine marriage.

The theme of mortal love ascending to celestial heights mirrors Francesca’s journey from outsider to noblewoman, formally recognized through their grand wedding held in the villa. Just as Psyche is ultimately accepted by the gods, Francesca is elevated in status, sealing Chigi’s love in both history and art. In this way, the loggia is not merely decorative; it is a visual testament to love’s power to transcend barriers, reinforcing the villa’s role as both a stage for opulence and a deeply personal monument to Chigi’s persona.

The Hall of the Perspective

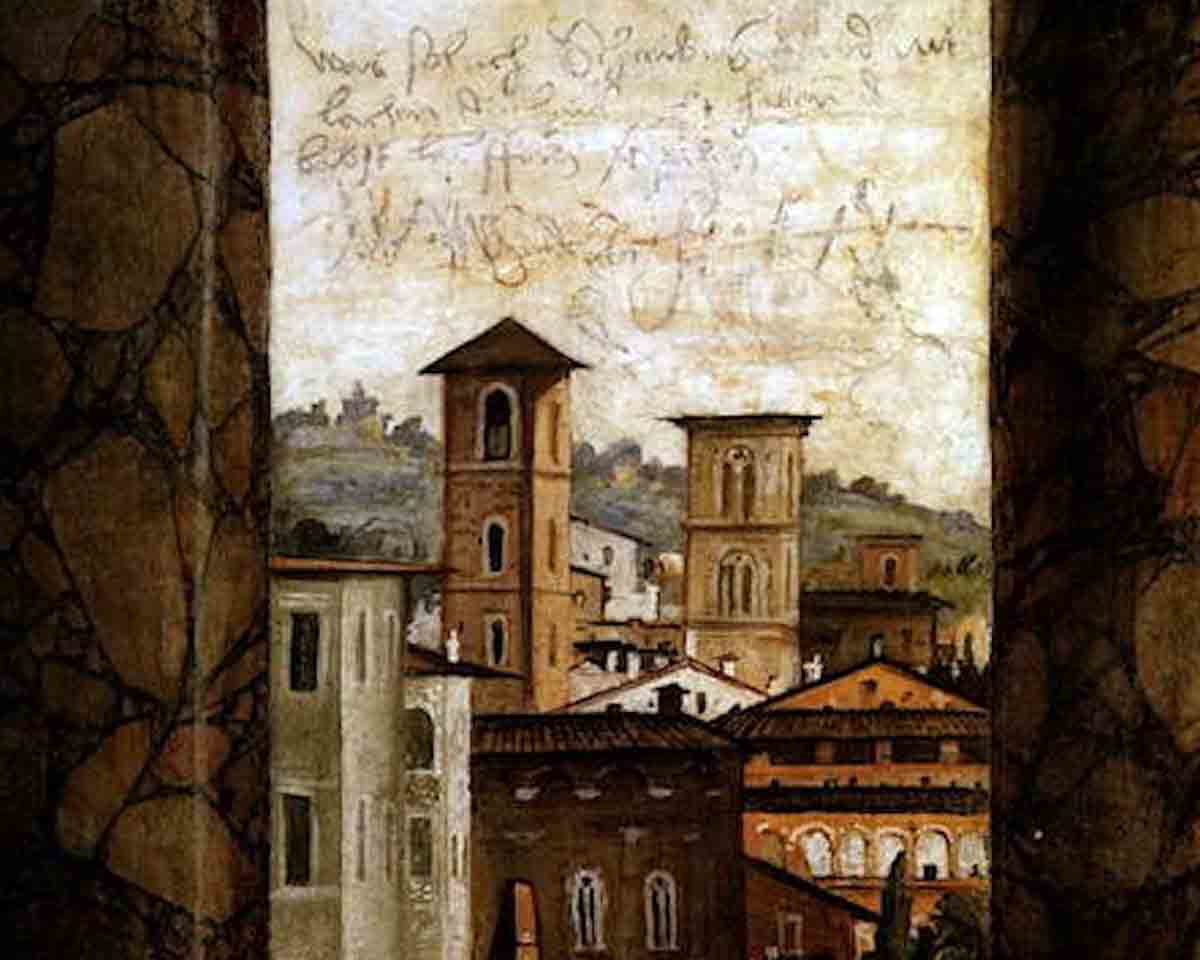

The Hall of the Perspectives is a fascinating example of Renaissance illusionism, where art masterfully dissolves the boundaries between interior and exterior. Designed by Baldassare Peruzzi, the frescoes transform the villa’s walls into an open-air loggia overlooking Rome, creating the illusion of vast countryside landscapes framed by elegant columns and arches. Through meticulous use of linear perspective, Peruzzi extended the space beyond its physical confines. The seamless integration between architecture and painting reinforces the villa’s identity as a retreat of pleasure and leisure, where reality and fantasy coexist in perfect harmony. The optical illusion also serves a symbolic purpose, reflecting Agostino Chigi’s wealth and influence, suggesting that his reach went far beyond the walls of his residence.

However, the Hall of the Perspectives also bears the scars of a more turbulent chapter in the villa’s history. During the Sack of Rome in 1527, the city was brutally ransacked by the Landsknecht, the German mercenaries of Emperor Charles V. These soldiers, largely composed of Lutheran troops, defaced parts of the frescoes by drawing crude graffiti onto the walls, priding themselves on having caused even the pope to escape.

Room of Alexander the Great in Villa Farnesina

Finally, the Room of Alexander the Great reflects Agostino Chigi’s desire to align himself with one of history’s greatest rulers. Painted by Il Sodoma, the frescoes depict key moments from the life of Alexander, including his legendary wedding to Roxana, which takes a central position on the main wall of the room. This scene presents a theatrical scene where Alexander approaches the reclining bride, a visual parallel to Chigi’s own marriage to Francesca Ordeaschi. Through this imagery, Chigi cast himself as a modern-day Alexander, a man whose wealth and influence were so vast that they rivaled those of the greatest leaders of antiquity.

Villa Farnesina’s legacy to the classical world is indeed profound, serving as a bridge between antique ideals and Renaissance humanism. Unlike Rome’s palaces, which often sought to evoke imperial grandeur, Villa Farnesina recalls the luxurious retreats of the ancient elite—rural villas where art, philosophy, and leisure intertwined seamlessly. The mythological frescoes, astrological motifs, and architectural illusions all harken back to Roman villa culture, particularly the extravagant residences of emperors and aristocrats, such as Hadrian’s Villa at Tivoli. Through its celebration of classical mythology, its revival of lost artistic techniques like grottesche, and its integration of interior and exterior spaces, the villa became a model for subsequent artistic movements, influencing Mannerist and Baroque aesthetics.

Villa Farnesina stands as an exquisite example of the Renaissance’s engagement with art, mythology, and classical antiquity. Unlike the imposing palaces of Rome, built to project political dominance, this villa embodies a different kind of power—one rooted in beauty, intellect, and the pleasures of refined living. Through its extensive frescoes, illusionistic architecture, and rich symbolic program, it transforms the ideals of antiquity into a personal and poetic visual narrative, reflecting both Agostino Chigi’s ambition and the broader cultural aspirations of the period.