Summary

- Spinoza’s Tractatus Theologico-Politicus (1670) critiques religion as a political tool.

- He argues religion’s value lies in its ability to instill moral principles, not in conveying divine truths.

- Spinoza dismisses superstition as a set of behaviors derived from scripture.

- He emphasizes the importance of religious tolerance and the separation of religion from state power.

- Spinoza views God as nature, rejecting transcendental concepts of God.

- His political philosophy advocates for a sovereign who uses religion pragmatically to maintain order.

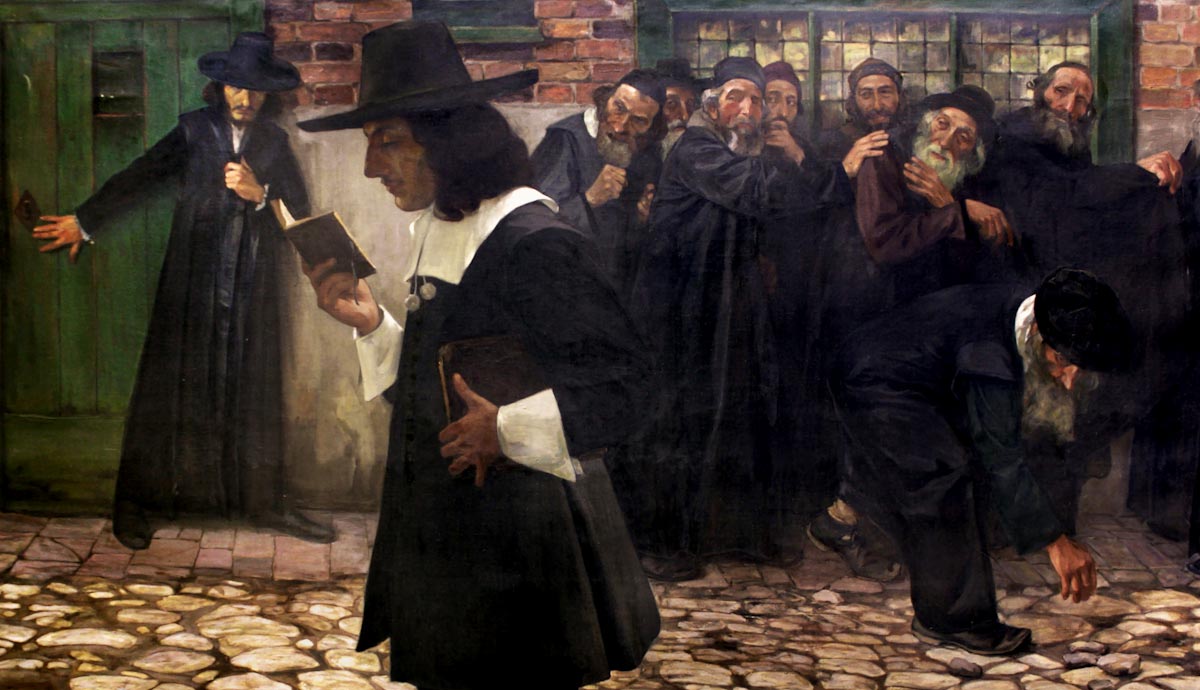

Baruch Spinoza’s philosophy reshaped the boundaries of religion and politics. Known for his controversial ideas, he remains a key figure in debates over the role of religion in society. Was Spinoza’s critique of scripture a denial of God, or a groundbreaking approach to political theory? This article explores his radical views on religion, scripture, and the state—as outlined in the Tractatus Theologico-Politicus—and examines his lasting impact.

Spinoza’s Tractatus Theologico-Politicus: Redefining Religion and Politics

Spinoza seems to have been, effectively, an atheist, or at least to have such a radically different conception of God from his religious contemporaries that he was certainly read as one. Spinoza decided to analyze the function of religion in the Tractatus Theologico-Politicus (1670) (TTP), primarily as an instrument of government.

He considers religion to be a tool by which obedience can be encouraged and through which simple moral imperatives can be effectively communicated. The resulting political disposition is undoubtedly Hobbesian, with a strong emphasis on the necessity of a lone sovereign under whose control all religious authority is placed.

What is conspicuously absent from Spinoza’s account of religion is any suggestion that religion—any religion—possesses transcendental truths or insights that are valuable in their own right.

The effective dissolution of natural rights and normativity in Spinoza’s political philosophy leaves the rest of the prescriptions made in the TTP as purely pragmatic.

The sovereign is no more obliged to practice religious toleration than the individual is obliged to act in any particular way; what matters, always, is only the increase or decrease in one’s power of action, and Spinoza thinks freedom of religion is an effective way for the state to discourage unrest and revolution.

The picture that emerges is of a thinker who is not overly concerned with the doctrinal truth of any particular religion. Rather, he is primarily concerned with stripping away religious obstacles to acting in accordance with the truth furnished by philosophy.

In one of the many claims in the Tractatus deemed heretical, Spinoza suggests in the preface that religion does not furnish believers with knowledge. Instead, it offers a set of moral principles, whose widespreadness and dutiful observation are important to the efficient and harmonious function of the state.

Spinoza’s Dismissal of Superstition in Religion

The TTP’s preface begins on a note of strident dismissal. Spinoza signals that his project is to disentangle the usefulness of religion from the baggage of superstition and fantasy.

He identifies superstation as a broad set of beliefs and behaviors, many of which find their origin in scripture. Spinoza is remarkably unconcerned, given the text’s avowedly theological nature, with any particular religion. Indeed, the valuable parts of religion he identifies—above all, religion’s ability to instill certain moral values, including absolute obedience—span denominations.

Spinoza’s View on Miracles and Scripture

In short, Spinoza’s religious commitments are so unlike those laid out in Judaism or Christianity that the differences between the two can readily be neglected. The scriptural differences between the two fall under the umbrella of ceremony and superstition, from which he wishes to separate the moral core of religion.

To this end, he asserts that religion, whatever its political virtues, is not a source of knowledge. This gesture did little to defend Spinoza against accusations of heresy.

The extreme controversy surrounding the TTP cemented Spinoza’s already substantial reputation as a heretic, with his various dismissals and critiques of scripture featuring extensively in damning contemporaneous commentaries on the text. Spinoza denies the purported truths of scripture, attempts to refute the Pentateuch’s divine origins, and denies the reality of miracles.

Miracles and biblical stories are, in large part, read by Spinoza as allegorical: ways of communicating religious morality to the masses rather than as historical facts. After all, if God is nature, as Spinoza believed, and his laws are natural ones, it is hard to maintain that God expresses Himself through violations of those laws.

Spinoza’s Naturalism: God as Nature and the Nature of Humanity

In a similarly deflationary manner, Spinoza wants to render human beings as essentially corporeal, possessed of souls only insofar as they are alive. What goes missing, here as in his Ethics, is any notion of the transcendental. Spinoza emerges, for all his talk of an infinity of attributes, as a materialist first and foremost.

As in his Ethics, Spinoza in the TTP wants to substitute a naturalist conception of God and religion for a doctrinal one. He offers that by extension of his definition of God as substance. Under God’s material attribute as nature, it seems intuitive to say that ordinary facts about the natural world constitute revelation.

Spinoza’s emphasis on divinizing this kind of “ordinary knowledge” takes some of the atheistic sting out of his critique of scripture. However, his emphasis on superstition and on various scriptural contradictions makes it clear that his primary concern is negative rather than positive.

Private religious belief is, for Spinoza, strictly up to individuals, not so much because they should have this right but because belief is practically difficult or impossible for the sovereign to police. However, the question of “how one is obliged to obey God” is strictly to be answered by civil authorities.

“God has no special kingdom among men except in so far as He reigns through temporal rulers,” Spinoza writes, and with this constraint drastically undercuts the power assumed by contemporaneous spiritual authorities.

Spinoza appeals to the ideal of Moses, as both temporal and spiritual leader, in order to ground his case in scriptural precedent, but his phrasing suggests something more radical.

Spinoza’s View on the Role of Spiritual Rulers

So what does Spinoza believe the role of spiritual rulers to be? “In the state of nature,” Spinoza suggests, “we could not conceive sin to exist […] there being no difference between pious and impious, between him that was pure (as Solomon says) and him that was impure”.

In short, it is not just that Spinoza thinks temporal rulers are necessary in order to relay God’s law, but that they are its first instantiation, before which there exists no transcendental morality.

Given Spinoza’s other comments on the purpose of law and the importance of religion as an instrument for the sovereign to extract obedience from his subjects, it is hard to maintain that Spinoza’s advice on the political uses of religious doctrine has anything to do with the kind of real and binding prescriptions found in the Ethics.

Spinoza’s Political Pragmatism and Religious Tolerance

Curiously, in this section of the TTP, Spinoza alludes to values of justice and charity that appear nowhere in his Ethics. We get a picture of a law which, whatever its ostensible connections to the Mosaic commandments, is born out of political pragmatism. He notes the expediency of ideas like damnation and paradise for keeping subjects in check.

Spinoza’s insistence that the civil authority should make all decisions concerning public religious practice and expression is seemingly based on political pragmatism rather than spiritual concerns. Spinoza does not comment on any particular religion being the rightful spiritual arm of the sovereign. Rather, he advocates for a kind of religious tolerance.

What, though, is the aim of Spinoza’s pragmatism? Many of his commentators read his comments on religious tolerance and the separation he proposes between religion and philosophy as thinly veiled responses to the theological turmoil of the 17th-century Dutch Republic. This perhaps explains the tension between Spinoza’s apparently liberal religious policy and his Hobbesian view on rights.

At other times, however, Spinoza stresses that his politics proceeds from his ethics. The principles he lays out aim to construct a harmonious state where everyone can maximize their own interests.

The Pragmatic Politics of Spinoza: Religious Authority and the State

If we take Spinoza’s view seriously, then his engagement with religious policy appears as an attempt to clear the ground of interfering obligations. After all, by Spinoza’s lights, the distinctions between good and bad actions do pre-exist temporal rulers. Not all ethical values are as politically contingent as scriptural ones.

Spinoza’s distinctive conception of God as nature and natural laws lends his political philosophy a secular quality. This contributed to his reception as a heretical thinker. Partly as a result, Spinoza is largely read as a straightforward Hobbesian. However, underlying his political project is something different: an understanding of power and its relation to the good that is decidedly his own and that flows from the propositions of the Ethics.