World War I was the deadliest conflict of its time. In 1914, leaders on both sides expected the hostilities to be over in months. Instead, the war bogged down into trench warfare in Western Europe while fighting spread around the world. In a desperate race to win, the combatants introduced and improved upon weapons of destruction. These included tanks, trenches, machine guns, poison gas, dreadnoughts, and airplanes. Read on to discover more about the weapons in the First World War.

World War 1 Tanks

Initially, the Western front in Europe became a mobile battlefield. Armies reacted with rapid movement. However, the First Battle of the Marne in September 1914 stopped the German advance into France and initiated years of static trench warfare.

To break the impasse, Britain worked on a new mechanized weapon. Although the idea of an armored vehicle started before World War 1, the concept was discounted until trench warfare led to calls for military innovations to break the impasse.

In 1915, the War Office initiated a “Landships Committee.” The Committee approved a design of an armored car with wheeled tracks, naming them “tanks.” In February 1916, 100 tanks were ordered from the British Ministry of Munitions.

Engineers designed the new Mark I tank to cross barbed wire and push over wide trenches. Machine guns were placed in a position to fire into enemy lines. Some tanks also carried guns for heavier artillery-type firepower.

Following intense testing and training in claustrophobic hot and loud conditions, tanks, manned by a crew of eight, were put into action in September 1916 during the Battle of the Somme. On September 15, the British attacked German trenches near the French village of Flers.

Almost 50 tanks were dispersed among advancing infantry for the offensive. However, numerous units broke down before seeing action, while others stopped working or became stuck during the fighting. In the end, only nine tanks pushed through German lines. However, lack of coordination with the infantry left them isolated and forced to turn back.

The use of tanks in this first battle was a limited success. Still, it worked well enough to convince British commanders to continue to use the armored weapon. The French and Germans also produced tanks for the battlefield to varying successes.

World War 1 Trenches

Perhaps the lasting image of World War 1 is life in the trenches. While sometimes used in previous conflicts, such as the American Civil War, in 1914, trenches became a staple of warfare in Western Europe. Their main purpose was to protect soldiers and equipment from enemy fire.

475 miles of trenches were dug on the Western Front. They were usually six to ten feet deep, with sandbags lining the top for protection.

Between the Allied and German trenches was an area with barbed wire and booby traps, known as “No Man’s Land.” This was where infantry had to cross to attack the enemy side. Sometimes, an enemy trench was captured, forcing the defeated side to retreat to a new one further back in the lines.

Daily life for troops in the trenches was dull, dangerous, and dirty. Much of the time was spent waiting for an attack or an order to counterattack. Soldiers occupied their time by playing cards or writing letters home. Rest periods behind the lines broke long spans of time in the trenches.

In addition to boredom, life was always dangerous. Artillery fire might land in a trench, causing it to collapse and crush the men within it. Peeking out above the sandbags could lead to instant death by a sniper’s bullet. Attacking enemy lines was a harrowing experience, running across the “No Man’s Land” while dodging barbed wire, mines, and bullets.

Daily trench life involved battling cold mud, rainwater, rats, lice, and disease. Millions of rats made life miserable for soldiers, spreading disease and contaminating food. Lice were everywhere, leading to constant discomfort as well as trench fever, a disease with bouts of pain and fever.

Machine Guns in the First World War

Machine guns were a staple weapon in the First World War. Indeed, it was their lethal effectiveness, along with artillery, that forced war into the trenches.

Developed in the late 19th century, these destructive weapons were deployed early in the new conflict. The first machine guns used in World War 1 were heavy and difficult to move. They required four to six operators. The equipment frequently jammed or overheated.

The German army adopted the technology earlier than the Allies. In August 1914, Germany had 12,000 machine guns while the British and French stock was in the hundreds.

Machine guns were effective as both defensive and offensive weapons. Their use against infantry attacks proved highly effective, resulting in high losses. On the opening day of the Somme Offensive, attacking British forces suffered 60,000 casualties, the majority of them from heavy machine gun fire.

Later in the war, machine guns were also used as offensive weapons. The weapons, for example, began to be attached to tanks and airplanes. In particular, the machine gun barrage became a popular tactic. Large numbers of guns were grouped together and fired repeatedly to form a steady barrage. The barrage supported offensives by firing over the heads of friendly troops into enemy positions.

Throughout the war, the race was on to develop lighter, portable machine guns. By 1917, most nations were using lighter equipment, making military strategies more flexible and mobile.

While deaths due to machine gun fire were enormous, German military historian Jack Sheldon attributes the rapid-fire gun to prolonging the war. According to Sheldon, the increased production and deployment of machine guns helped Germany substitute depleting manpower and continue the war well into 1918.

Poison Gas

Several gas chemicals were used in World War 1. The first time was by the French, who used tear gas against the Germans in August 1914. Although irritating, it was neither fatal nor considered effective.

In January 1915, the Germans first used gas against the Russians on the Eastern Front, where the German artillery shot shells of a different type of tear gas toward the Russian lines. However, this also proved ineffective as the cold temperatures quickly dissipated the poison.

The most effective use of poison gas occurred at the Second Battle of Ypres in April 1915. There, the Germans released poisonous chlorine in canisters. Chlorine irritated the soldiers’ lungs, often proving fatal. The attack caused confusion and panic among Allied lines, with significant casualties.

The British launched their own gas attack using chlorine against German lines in September 1915. However, winds caused the gas to blow back into the advancing British troops.

Protections against chemical weapons evolved over time. The first defense was simple: using linen masks soaked in water. Only later were the more practical gas masks with respirators issued to front-line troops.

July 1917 witnessed the release of the more lethal mustard gas. What made this gas so deadly was that it got into the lungs, as well as the skin. Mustard gas caused the skin to painfully redden and blister. Even the eyes were susceptible, which sometimes led to blindness.

The use of poison gas by both sides caused massive physical and psychological devastation. With widespread use, soldiers adopted more effective protections. Like tanks and machine guns, poison gas caused more casualties but was not the knockout blow either side was hoping to achieve.

Dreadnoughts

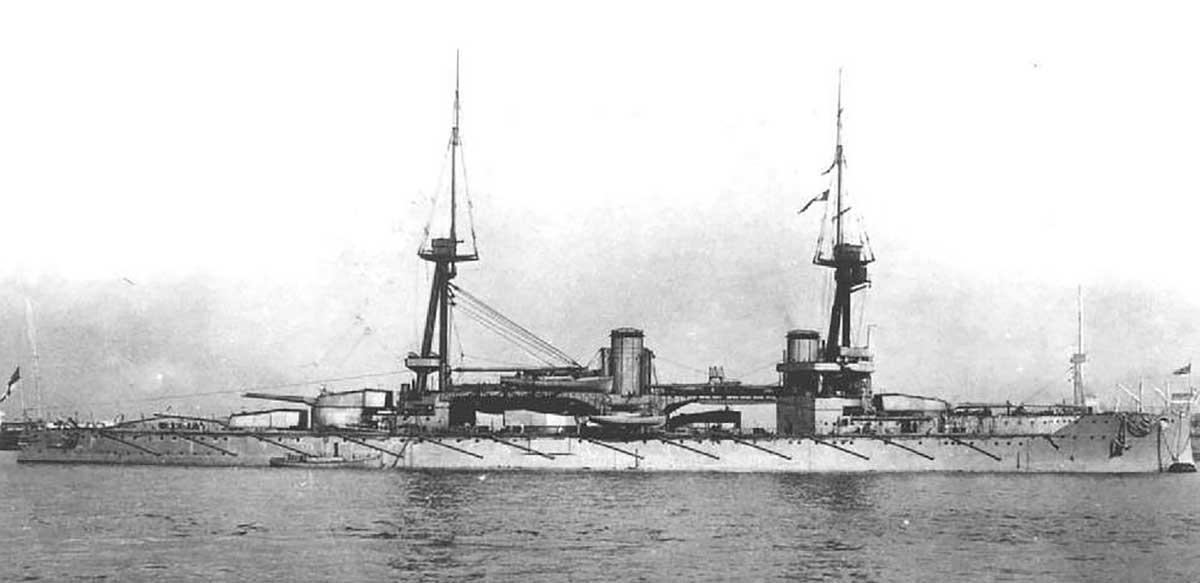

In 1906, the new British battleship HMS Dreadnought first sailed. It was the largest military vessel of its time and launched the age of the dreadnoughts: giant battleships with size, speed, enormous firepower, and modern turbine engines.

The turbine engines allowed speeds of up to 25 miles per hour. The increased number of guns on the ship overpowered other warships. The arms race of the dreadnought class battleship had begun.

In the late 19th century, Britain was the dominant sea power. However, the German Empire was determined to achieve parity with the British, along with the United States, France, and Japan. While these other nations were far behind in the number of warships, the new battleships made most previous vessels obsolete, creating a rush to build them quickly.

The biggest shipbuilding rivalry was between the British and Germans. By the beginning of the war in 1914, Great Britain had 29 dreadnoughts compared to 17 for Germany. Some historians say the dreadnought rivalry was a big factor leading to the First World War.

In the early years of the war, the two main naval rivals adopted separate strategies. The British employed a blockade of Germany using their naval dominance. The German plan put U-boats (submarines) into action to sink enemy shipping.

Interestingly, only one major battle between dreadnoughts took place: the Battle of Jutland in May 1916. German U-boats and battleships attempted to lure the British fleet into battle, which countered by sailing towards the German line.

Despite the German fleet inflicting more damage on British ships than they themselves suffered, the battle of the dreadnoughts ended in a stalemate. The British were unable to crush the German fleet, while the Germans realized they could not outgun the British navy.

The age of the dreadnoughts was short. Aircraft carriers soon replaced them.

Airplanes

After the Wright brothers’ first flight in 1903, air travel was still in its infancy when World War 1 began. Leaders on both sides first decided to use airplanes for scouting and reconnaissance rather than direct combat.

Air tactics soon progressed to prevent enemy planes from spying on troop movements. Pilots were equipped with pistols and grenades. However, these light weapons proved ineffective in combat, and more lethal methods were developed.

Heavier machine guns needed to be mounted on planes for increased firepower. The best way to support the extra weight was to add a second stacked wing, known as a biplane. The Germans were the first to develop the Fokker aircraft with a working machine gun that could synchronize firing through the propeller without damaging it.

People viewed pilots as the noble knights of combat, replacing the cavalry on horseback that were mowed down by gunfire early in the war. Biplanes roamed freely in the air, free of the mud and rats of the trenches. Most pilots came from the officer classes, adding prestige to their roles. Some gained further fame as “Air Aces,” bringing down multiple enemy planes.

Perhaps the most famous fighter pilot of the Great War was Germany’s ace Baron Manfred von Richthofen, better known as the Red Baron. The Red Baron flew a red-colored triplane, which was considered better for climbing and turning ability. He is credited with 80 confirmed planes shot down. The Red Baron perished in April 1918. Sources credited an Allied pilot with the kill, although the later consensus was the Red Baron died from anti-aircraft fire from the ground.

The Allies had several of their own ace pilots with dozens of planes downed between them. They included France’s Rene Fonck, Canadian Billy Bishop, and Irish-born Mick Mannock.

The weapons innovations of the First World War worked with devastating effects. What many expected to be a short war instead became a mechanized bloodbath. Many weapons evolved or changed after the war. Tanks and machine guns became more powerful. Generals avoided using poison gas and prolonged trench warfare. More sophisticated warships replaced dreadnoughts, and airplanes became bigger, faster, and more lethal.