The Anglo-Saxon aristocracy, many of whom had fought and died with King Harold Godwinson at Senlac Hill, were systematically shorn of their landed wealth after 1066. In their place stood the Norman aristocrats whose superior skill at arms had granted them victory on that fateful day.

The Domesday Book, compiled in 1086, bears witness to this change. William the Conqueror’s kinsmen and companions had in this 20-year period managed to claim and hold down possession of vast new estates. But how did the Normans decide to which victor went which spoils, and how did they justify it to the dispossessed?

The Norman Conquest Through Norman Eyes

There is much that is contentious about the years immediately preceding the Norman Conquest, during Edward the Confessor’s reign. When recounting the Godwine family’s exile in 1051, for instance, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle describes how “Soon after came Duke William from beyond sea with a large retinue of Frenchmen; and the king entertained him and as many of his companions as were convenient to him, and let him depart again.” This tantalizing reference has been agonized over by generations of scholars since it is the only Anglo-Saxon source to acknowledge that Edward the Confessor was even aware of William of Normandy. Had Edward made an offer of the crown to William, we might expect that the chronicler could hardly omit reference to it. If the chronicler was opposed to the claims of Duke William, it is far more likely that he would not have mentioned it at all.

If the Anglo-Saxon sources are entirely ambivalent about William’s position prior to 1066, Norman chroniclers were polished in the presentation of their narrative. The most detailed account is to be found in the Gesta Guillelmi (Deeds of William) written by William of Poitiers, easily the most panegyric of the chroniclers. Contrary to his toponymic, William was in fact a Norman who had trained as a knight before entering the church around 1049. He began work on the Gesta Guillelmi sometime after 1066, with the bulk of the work taking place in the 1070s. William’s overwrought and bloated prose sought to cast William of Normandy as a kind of medieval Caesar, with classical allusions ad nauseam to drive home the point.

Yet as a propagandist, William had no equal. The narrative he tells is that Edward the Confessor had offered William the crown, and sent Harold Godwinson as an envoy to confirm this pledge since “Harold’s wealth and authority could check the resistance of the whole English people, if, with their accustomed fickleness and perfidy, they were tempted to revolt.”

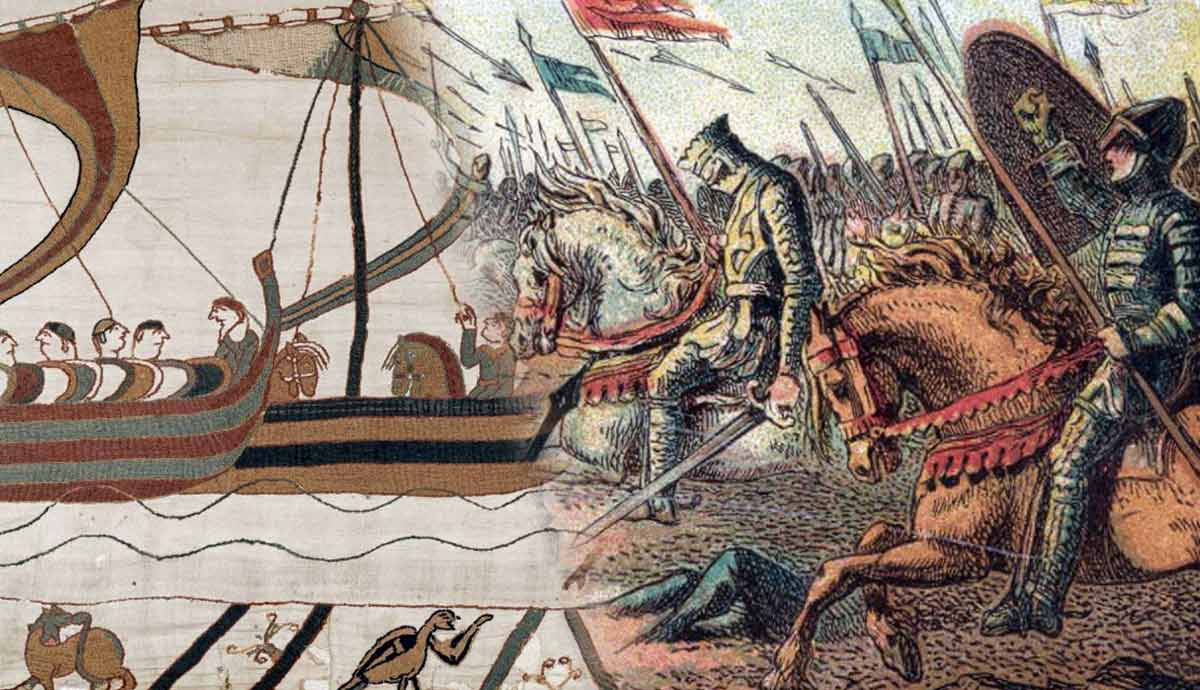

After rescuing Harold from the clutches of a discontented vassal, Count Guy of Ponthieu, Harold is said to have pledged his fealty to William, and that “he would strive to the utmost with his counsel and his wealth to ensure that the English monarchy should be pledged to him after Edward’s death.” That this is closely corroborated by scenes from the Bayeux Tapestry does not necessarily suggest its veracity: it merely reflects the existence of a carefully crafted, consistent narrative on the events leading up to the Norman Conquest, after the fact.

Harold’s subsequent breaking of this oath and his assumption of the throne upon the death of Edward the Confessor in 1066 was excoriated by the Norman chroniclers. William of Poitiers describes how “on the tragic day when that best of all men was buried, while all the people were mourning, he violated his oath and seized the royal throne with acclamation, with the connivance of a few wicked men.” William of Poitiers made clear that it was Stigand, who had not received the pope’s blessing upon becoming Archbishop of Canterbury and was thus uncanonical, who crowned Harold.

Later Norman sources would airbrush out any record of Harold having been king entirely. Chief among these was the Domesday Book, which acknowledges only the reigns of Edward and William, and describes Harold merely as an earl.

Harold was, therefore, in Norman eyes, a perjurer, since he had violated an oath sworn upon sacred relics. It was therefore clear to chroniclers writing in retrospect that, with papal approval, William was always to be assured of victory by divine providence. Yet in order to press his claim William needed to rely on manpower provided by loyal vassals. These played no small part in William’s victory, and in shaping the society that emerged after the Norman Conquest.

“They Came Over With the Conqueror”

Much as the chroniclers tried to present William of Normandy’s victory as the result of his leadership alone, his kinsmen and supporters played a key role in raising an army for him. In the historiography, the strength of William the Conqueror, king of England tends to overwrite the weakness of William, Duke of Normandy. Knightly service, where mounted warriors were expected to serve for a fixed period each year (usually forty days) in exchange for the land they held from their lord (and ultimately the ruler), is a central pillar in the modern understanding of feudalism. Yet it was hardly established in Normandy by 1066, and possibly not before the reign of Henry I (1100-35).

While ducal power in Normandy had become more centralized under William and had grown to encompass the neighboring territories of Brittany and Maine, William’s success in the Hastings campaign was predicated upon aligning the interests of regional strongmen with his own. To do this, he had to persuade his vassals to fully commit their resources to an enterprise in which he promised they stood to gain. It was not in William’s power, nor necessarily in his interest, to enforce participation from the Norman aristocracy.

Where coercive power was lacking, William could turn to common ties of kinship and alliance between himself and his vassals. As historian Eleanor Searle points out, William’s predecessors as duke had been wise enough to marry their female relatives and in-laws to local strongmen to tie them to the ducal house without giving them claims on the duchy itself.

Most prominent, and loyal, among William the Conqueror’s vassals were his half-brothers through his mother Herleva: Robert, Count of Mortain, and Odo, Bishop of Bayeux. These were two of the leading lights in Norman politics with their own power bases in the west of Normandy, and they were able to bring considerable resources to bear in support of William.

No less prominent were William fitzOsbern, a cousin of William with extensive lands in the east of the duchy, and Roger de Montgomery, another cousin and a formidable strongman in the south who had married the heiress to the semi-independent territory of Bellême, Mabel. Before invading, the prospective participants met at the Council of Lillebonne to discuss the pros and cons.

Orderic Vitalis, a chronicler writing in the early 12th century, describes the reservations of many of the great noblemen gathered there. He describes that several were hesitant about undertaking such a risky enterprise as a seaborne invasion, and that “there were many dangers and difficulties in the path of the overbold who were heading for destruction.”

William FitzOsbern and Duke William himself seem to have played a key role in winning the hearts and minds of those present. An interesting 12th-century document from Battle Abbey, known as the Ship List of William the Conqueror, recounts the resources that each of the major magnates contributed to the venture. The document lists 14 vassals, of whom at least ten were relatives of William.

Walter Giffard, the old but powerful lord of Longueville, is said for instance to have contributed 30 ships and 100 knights. Others who were younger and just starting out in their military careers, such as William de Warenne, may have made whatever contribution of resources that they could at that stage.

We know the names of many participants at Hastings from written sources such as William of Poitiers and Orderic Vitalis. At points, we even glimpse their presence on the battlefield. The Bayeux Tapestry, though mentioning few Norman nobles by name, gives a prominent position to Odo of Bayeux, the putative patron of the work. Although, as a bishop, Odo was not permitted to spill blood, he can be seen in full armor supporting a squad of Norman knights during the battle. His use of a mace, or club, may have been a clever way of circumventing what was forbidden, since causing internal bleeding and hemorrhaging may not technically have counted as “spilling” blood.

Odo, as a bishop, had no progeny and indeed was disgraced within his own lifetime. One instance that nearly ruined the magnate involved a hair-brained scheme to make himself pope by force, backed by a force of a hundred knights. Only the death of the Conqueror exonerated him.

Many of the men who established great noble families in England after the conquest, however, also fought at Senlac Hill. The families of Warenne, Beaumont, Clare, and Mandeville, for instance, would be given pride of place in the upper crust of an aristocracy that lasted into the Angevin period (1154-1216) and beyond.

Needless to say, William had to promise much to his vassals in return for their participation in the conquest of England. And he delivered on these promises. The Domesday Book decisively shows that by 1086 the Normans had entirely displaced the Anglo-Saxons in the upper echelons of the landholding aristocracy. The book itself, in fact, was part and parcel of the appropriation of land by incoming Normans at all levels, legitimating and rubber-stamping what Robin Fleming calls a “kleptocracy.”

Land Ownership in the Domesday Book

The Domesday Book set out to record land ownership in England as it existed at two dates: tempore regis Edwardi and tempore regis Willelmi. The first referred to the tenurial geography as it was on the day that King Edward “was alive and dead,” or January 5, 1066, while the second referred to the state of affairs when the finished book was presented to William, on Christmas Day 1086. Arranged by shire, and within this by landowner, it enables the historian to trace the impact of the Norman Conquest at the local level in minute detail.

Many books have been written on the Domesday survey itself, as well as the technicalities of land ownership as they appear in the Domesday Book. Our focus here, however, is on the principles regarding William’s allotment of land to the followers who had brought the military power of Normandy to bear upon English shores.

A few general phenomena can be glimpsed immediately. Firstly, the 20 years separating the Domesday survey from King Edward’s day witnessed a dramatic increase in the power of the king. The extent of land held by the king in demesne or through subtenants (distinct from land held “in chief” by William’s barons), calculated by its monetary value in pounds per year, more than doubled between 1066 and 1086, to encompass 20% of the total landed wealth in the country by the latter date. Barons held around 50% of the land and the church a further 20%.

A further observation that can be made is that William deliberately decided to allocate land to barons in several different shires that were often remote from one another. Aware, perhaps, of the overweening power that the Godwine family exercised over his Anglo-Saxon predecessor, the Conqueror would brook no rival.

Richly rewarded as the Conqueror’s companions were, virtually none were allowed to build up a concentrated territorial power base to match the king in any one county. The resulting pattern of landholding is a veritable mosaic of vills and manors standing side by side yet belonging to different lords. The PASE Domesday Project enables us to visualize this in detail. One leading baron, William de Warenne, whose landholdings were more concentrated than most, nevertheless found his manors spread across 14 counties, with the most valuable lands being in Sussex, Norfolk, and Yorkshire.

As to the particulars of the rationale underpinning William’s allotment of land, two patterns can be evinced. The first had to do with the identity of those that had held the land before the Norman tenant in question and was known as “antecessorial” succession. The second had to do with strategic considerations which cut across previous lines of landholding.

Antecessorial Succession

Antecessorial succession was an important guiding principle for the allocation of land after the conquest. In many ways, it can be thought of as mirroring the political narrative surrounding William’s own accession to the throne.

Legitimate title to land could be traced back to the day that Edward was alive and dead, but was thrown into doubt by the support of the Anglo-Saxon aristocracy for Harold. Key to the semblance of continuity from this earlier date that William was trying to construct was the idea that although legal title to the land had exchanged hands up and down the country, the incoming Normans were in fact no less than the heirs of the Anglo-Saxons they dispossessed.

In this way, the Normans may also have sought to mitigate the sense of shock experienced by Anglo-Saxon peasants on their new estates. The peasant subtenant might continue to render what was due to the landlord much as he had before, safe in the knowledge that his local, or tenurial, community, consisting of his own estate as well as others which through their landowner were associated with it, was delivered intact to the newcomer. In this way, estates were protected from what might otherwise have been a ruthless land grab.

This is not to say that Anglo-Saxons were all immediately dispossessed. Those who fell at Hastings left their lands conveniently vacant, or with heirs who could be brushed aside in favor of the incoming Normans. Other figures, such as the Earls of Mercia and Northumbria from the powerful family of Leofric, Edwin, and Morcar, did not immediately oppose William and thus probably held on to the bulk of their territories until later rebellions gave William just cause in confiscating their estates.

The principle of antecessorial succession, then, was both part of the rhetoric of conquest and a practical measure designed to minimize its upheaval at the local level. Sometimes a Norman landholder took possession of the estate of an Anglo-Saxon antecessor intact across multiple counties.

This was clearly the case with Geoffrey de Mandeville, an important post-conquest landowner who succeeded to the lands that had been held by Esgar the Staller across nine shires in what are now the home counties, East Anglia, and the south midlands.

In other instances, the principles of antecessorial succession were followed within the confines of one or more shires but did not encompass the entire landed estate. One instance of this is the lands of the pre-conquest Leofnoth, son of Osmund. His estates in Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire passed, more or less intact, to Ralph Fitz Hubert, while those in more southerly Northamptonshire and Bedfordshire went to Walter the Fleming.

This latter case suggests that, despite the Conqueror’s concern to prevent his magnates from establishing local power bases to rival his own, there was a definite geographical principle to the distribution of land after 1066. Part of the reason for this may lie in the aforementioned desire of the Normans to minimize the upheaval wrought by the conquest.

Shires were important political and juridical communities during the 11th century in a way that they no longer are in the twenty-first. To preserve the landholdings of a particular Anglo-Saxon noble intact within the confines of a shire was to ensure continuity. Estates belonging to the same landowner but located in different shires undoubtedly had far weaker associations and were more divisible, especially in the case of shires such as Bedfordshire and Derbyshire which were separated from each other.

In the case of the second and third rank of the Norman aristocracy, there was also far less risk involved in allowing individuals to succeed in consolidating blocks of territory, since this never involved their establishing local predominance and in fact might serve as a counterweight to other more powerful barons in the shire. Yet in the case of strategically important areas, the Conqueror made an important exception and allowed his barons to become the most important figures in their localities.

Compact Territorial Lordships

Though Hastings turned out to be a blow from which the Anglo-Saxons would never fully recover, it did not seem so to many in England at the time. There were no fewer than six revolts against William’s rule in the years 1067-75, led by major figures who were supported by powerful foreign potentates, such as the kings of Denmark.

Some areas in England, therefore, were perceived as being strategically sensitive and in need of powerful magnates to hold down the local population and defend the country from invasion. These magnates were given compact territorial lordships which would give them the economic and military resources to carry out their role. The majority of these lordships were centered around castles which would enable the Normans to subdue the local population and defend territory from attack.

One particularly sensitive area was Holderness, in the East Riding of Yorkshire. Situated on the northeast coast of England, Holderness controlled the entrance to the Humber estuary from the north. From the Humber, Viking forces were put within striking distance of York. Both Harald Hardrada of Norway and Swein Estrithsson of Denmark penetrated inland using the Humber in their respective invasions of England in 1066 and 1069.

Control of Holderness, therefore, was given in its entirety to Drogo de la Beuvrière. Though many of the estates had belonged to Morcar and Tostig before him as earls of Northumbria, Drogo’s lordship was cobbled together from the holdings of many other pre-conquest landholders. Though he was to be dispossessed in 1086, Drogo had by then built Skipsea Castle, to defend his lordship in Holderness.

The same may be said of the lordships in the Welsh marches. Here, powerful magnates such as Roger de Montgomery were given blocks of territory to defend from the incursions of independent Welsh princes based in Gwynedd and Deheubarth. Those whom the Conqueror placed here were the most powerful lords in the realm and could bring extensive resources to bear here from their holdings in both Normandy and England.

The Montgomery family, later earls of Shrewsbury, possessed a compact block of territory in Shropshire as well as extensive estates in Sussex, Hampshire, Staffordshire, and Cambridgeshire. The Earls of Chester, controlling the northern stretches of the Welsh border, were given extensive lands in Cheshire as well as valuable estates in Yorkshire, Leicestershire, and Lincolnshire.

Both of these figures were also among the most important landowners in Normandy, and so were tied into the new cross-channel polity that William had established.

Of greater interest are the “rapes” of Sussex. These seem to have been based on older territorial divisions, perhaps dating from the early Anglo-Saxon Period when Sussex was an independent kingdom. Despite their origin, it is clear that the rapes as they were in 1086 were Norman creations. This is evident from Domesday, which shows that strict geographical lines were drawn in the tenurial geography of Sussex, often cutting across pre-conquest patterns of landholding and even splitting parishes in half.

The Domesday Book itself makes reference to parts of estates that were “lost” to adjacent rapes. Ripe, despite seemingly belonging in its entirety to Harold Godwinson in 1066, was divided between Robert, Count of Mortain, and Robert, Count of Eu, who were lords of the rapes of Pevensey and Hastings respectively.

Although they are situated on the coast, these lordships do not have such an obvious military purpose as those in Yorkshire or on the Welsh marches. On the other side of the Channel was William’s own duchy of Normandy, and thus Sussex was not in immediate danger of foreign invasion. They undoubtedly served in part to keep this vital channel of communication open.

Yet it is also significant that Sussex was the heartland of the Godwine family, the most powerful magnates in England prior to the conquest. There may have been a sense that, unlike with other parts of the country, the tenurial geography of Sussex needed to be ripped up entirely.

The Conquest of England: A Magnate’s View

It is, unfortunately, too much to ask for an account detailing the experience of Anglo-Saxon peasants after the Norman Conquest. History, as the cliché goes, is written by the victors, and in the Medieval Period, it does not concern itself with the lives of ordinary people. There is, however, a chronicle that narrates the experience of conquest from the perspective of a magnate family at a more local level.

The Warenne (Hyde) Chronicle was written in the 1150s by a scribe associated with William, the younger son of King Stephen (1135-54) who had married the heiress to the Warenne family, Isabel in 1153. Elisabeth van Houts argues that it was in the context of ingratiating himself with the new king, Henry II, that William commissioned the chronicle in order to remind the king of the loyal service provided to the crown by Isabel’s family, and thus to seek royal favor for himself.

The primary interest of the text for our inquiry is in its account of the conquest which, although according to the received tradition in many aspects, also adds to it. The limits of historical memory as preserved in the Medieval Period by women within noble families, van Houts argues, stretch to around three generations. The Warenne Chronicle, then, is a fortunate written expression of a family tradition, at the very end of its shelf life, regarding the conquest.

The Bayeux Tapestry records that, during Harold’s supposed visit to Normandy, the earl made an oath to William upon sacred relics. The Warenne Chronicle furnishes the further detail that the relics were those of St. Pancras. It says, of Harold’s father Earl Godwin, that he was from a humble origin and that he became the most powerful magnate in England “more on account of his possessions and wealth than for the merits of a praiseworthy life.” It further stresses that, although powerful throughout England, “his principal county by far was the southern region, which in their language is called Sussex.”

The reference to St. Pancras as the saint over whose relics Harold swore an oath to William is significant since no other source makes reference to it. Within the Catholic church, St. Pancras is the patron saint responsible for the punishment of perjury. William I de Warenne, when establishing the first Cluniac monastery in England around 1081, dedicated it to St. Pancras. The chronicler also, uniquely, notes the Godwine family’s connection with Sussex and extensive landholdings there, demonstrating an unusual knowledge of the family’s history, especially since he was writing almost 100 years after Harold’s death.

What we likely have here, therefore, is a narrative formulated by the Warenne family itself that served to legitimate their possession of land formerly belonging to the Godwine family.

As the mainstream tradition goes, Harold committed perjury, and thus divine providence had moved to remove him from his position as king. The Warenne family, along with its neighbors, were the agents of divine retribution at a more local level, ordained by God to expropriate the lands of the Godwine family for themselves.

It is unclear how such a narrative may have been disseminated in its entirety at the time. Yet Lewes Priory, dedicated to St. Pancras, was arguably a memorialization of Harold’s sin in Caen stone. It can only have served to remind those Anglo-Saxons who were former tenants of Harold Godwinson in Sussex that to rebel in his name was to commit a grave sin and to share his fate.