What is a diptych? In its most recognizable form, the diptych consists of two parts. Usually joined with hinges, they present as one artwork and are most often paintings. Byzantine diptychs were among the earliest known pieces in this form. Unlike their better-known medieval and Renaissance counterparts, Byzantine diptychs were small, the size of the average paperback book, and were made of ivory. Whilst these intricately carved objects were impressive, it is the later, painted version, by Netherlandish artists like Hans Memling, which gained the most fame.

The Byzantine Calling Card: The Ivory Diptych

The forerunner of the painted diptych took the form of two carved ivory panels joined with hinges. Given as gifts or a form of calling card by newly elected Consuls, diptychs became an ostentatious gift given to show how far a man had risen in society. In the interior of the diptych were wax tablets used for writing, which could be melted and reused. These were eventually dispensed with, leaving the object as an expensive token for high-ranking officials.

Fit for a King: The Wilton Diptych Ushers in a New Era

A vision of stippled gold and deep ultramarine ground from the finest lapis lazuli, the Wilton Diptych is one of the oldest surviving examples of a painted diptych from the medieval period. Gone are the associations with extravagant gift-giving of the Consular diptychs; this gilded treasure is believed to have belonged to King Richard II of England, used for his private devotional worship. Its dimensions of 21 by 14.5 inches made it eminently portable on the King’s travels.

The panels are painted in egg tempera, a medium composed of egg yolk, pigment, and water. This was the most commonly used medium for painting before the development of easily workable oil paint in the 15th century. The artwork has proven to be a conundrum to art experts. Its style suggests Sienese influences, although the use of egg tempera is more redolent of Italy. It is painted on oak, suggesting a Netherlandish work. In addition, the artist’s name and nationality are unknown.

The left panel depicts a kneeling King Richard being presented to a heavenly assembly on the right-hand panel by three saints, particularly relevant to his life: King Edmund, King Edward the Confessor, and Saint John the Baptist. Richard and his saints are located in a barren landscape, simple and bare despite the golden robes of the King. The angels on the opposing panel luxuriate in a field of flowers. Visible on the angels’ robes and the breast of the King is his personal device, the white hart (mature stag). The pennant of Saint George, a reference to England, flies over the assembled host as a further reminder that this artwork is not just a devotional item but a status symbol for a King. Once closed, the diptych’s outer panels repeat Richard’s emblem, the white hart, and his coat of arms.

The Netherlandish Diptych

The Wilton Diptych was extraordinary in that, for such a high-profile object, it could not be attributed to a particular artist or location. As the 15th century dawned, however, the production of diptychs shifted to the Netherlands. In particular, well-known artists like Jan van Eyck, Hans Memling, and Rogier van der Weyden became experts in the field.

Van Eyck’s Annunciation, also known as The Thyssen Diptych, is an extravagant display of the skill and innovation for which the artist was famous. Painted in oil on oak using the grisaille technique, the diminutive panels, measuring a total of 15 by 18 inches, bear exquisite renderings of stone statues of the Virgin and the Angel Gabriel. The three-dimensional qualities achieved by van Eyck, mimicking even the tones of different types of stone, are almost tangible. Although the commissioner of the diptych is unknown, the piece was likely used for private worship.

The Personal Touch: The Devoted Patron at Home

As the century progressed, wealthy patrons began to commission small diptychs for personal use, often featuring their portrait. Conceived as a way to show their veneration of a chosen saint, such as their holy namesake or the Virgin and Child, these artworks could also be seen as a symbol of the individual’s standing in society. Often, they dispensed with the idea of their being surrounded by guiding saints, ready to speak to God on their behalf. These men preferred to make their case for salvation personally.

Hans Memling’s diptych for Maarten van Nieuwenhove took the theme of personal devotion to the extreme. The right-hand panel shows the patron in his own home. The scene outside his stained-glass windows is identifiable as Bruges, where he was born into a wealthy family of influential men. The windows, featured in both van Nieuwenhove’s portrait and the image of the Virgin and Child, depict his family’s coat of arms and emblem—a new garden (Nieuwenhove).

A popular device of the time in Netherlandish art also features the convex mirror. Van Eyck used the convex mirror as a symbol of divine presence, but ultimately, it may just have represented the artist showcasing his skill, just as much as the patron was showing off his wealth. In this panel, the mirror reflects the patron and the Virgin and Child in the same circular field—the worshiped and the worshiper brought together.

The panel showing the Virgin and Child repeats the Bruges background, and her presence in the patron’s home may be responsible for the look of awe on his face. The use of such an intimate and private space in diptychs like this points to the patron’s commitment to worship. Although van Nieuwenhove would likely be the only viewer of the diptych, its portability (being another small piece) would mean it could travel with him. When closed, the outer view would be of his family’s coat of arms on its covers.

Diptychs at the French Court in the 15th Century

Whilst the Netherlandish painters of the 15th century were acknowledged as masters of the art form, nobles and statesmen at the courts of France and Italy were commissioning artists in their own countries to produce equivalent artworks. The Melun Diptych by Jean Fouquet was painted for Étienne Chevalier, who is pictured kneeling at the side of his patron saint, Stephen, in the left-hand panel of the piece. The diptych is named for the Collegiate Church of Notre Dame in Melun, where it was first kept.

Chevalier was the treasurer to King Charles VII of France. A trusted and high-ranking official to the court, Chevalier had once acted as the French Ambassador to England. He was familiar with the work of Jean Fouquet, who had painted commissions for Pope Eugene IV and King Charles VII.

In the left panel of the diptych, we see Chevalier kneeling by the side of his patron saint, Stephen. Saint Stephen holds a stone, and blood drips from a wound on his head. These attributes illustrate his martyrdom, as he was stoned to death. The panel’s background is a traditional stone courtyard or building, elaborately carved and inset with marble, appropriate to Chevalier’s rank. The donor and Saint Stephen both look towards the right-hand panel in an attitude of worship and piety.

In stark contrast to the patron’s panel, the right-hand side of the diptych is a blaze of color. Whilst Fouquet paints the men in the left-hand panel in a realistic manner, his portrayal of the Virgin and Child surrounded by a host of angels is stylized and surreal. The Virgin and Child, their skin as white as her flowing robe, are stiff, static, and otherworldly. The Virgin’s breast is bared, but there is no softness of flesh. This is intended as an image to be worshiped, not as a realistic rendering of a mother and baby. It shows a queen and her prince on their bejewelled throne.

Whilst Mary wears the customary blue dress, the angelic assembly surrounding the Holy pair is anything but traditional. Gone is the white and gold associated with angels, and glowing halos are conspicuous by their absence. These messengers of God are cobalt blue and scarlet red. The image sends a message to humble Chevalier, a man of high status in his world, that the kingdom of Heaven is ethereal and beyond his reach. Only with prayer and by living a life without sin can he, with Saint Stephen by his side, enter this realm.

The Diptych as Portraiture

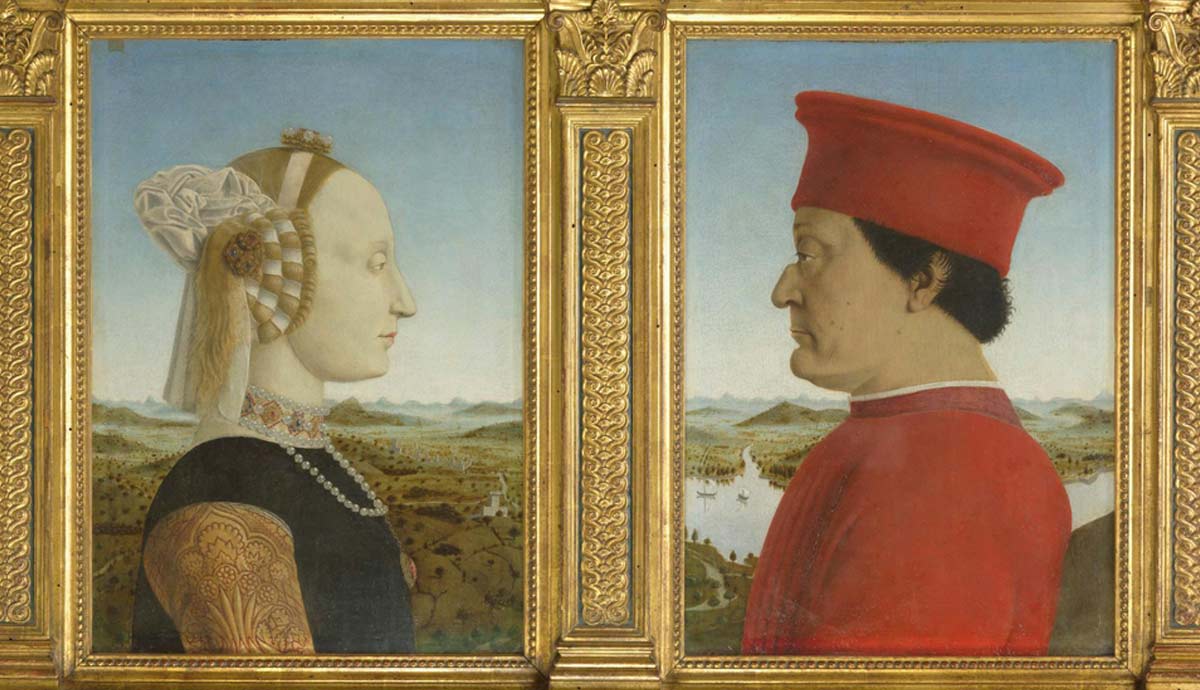

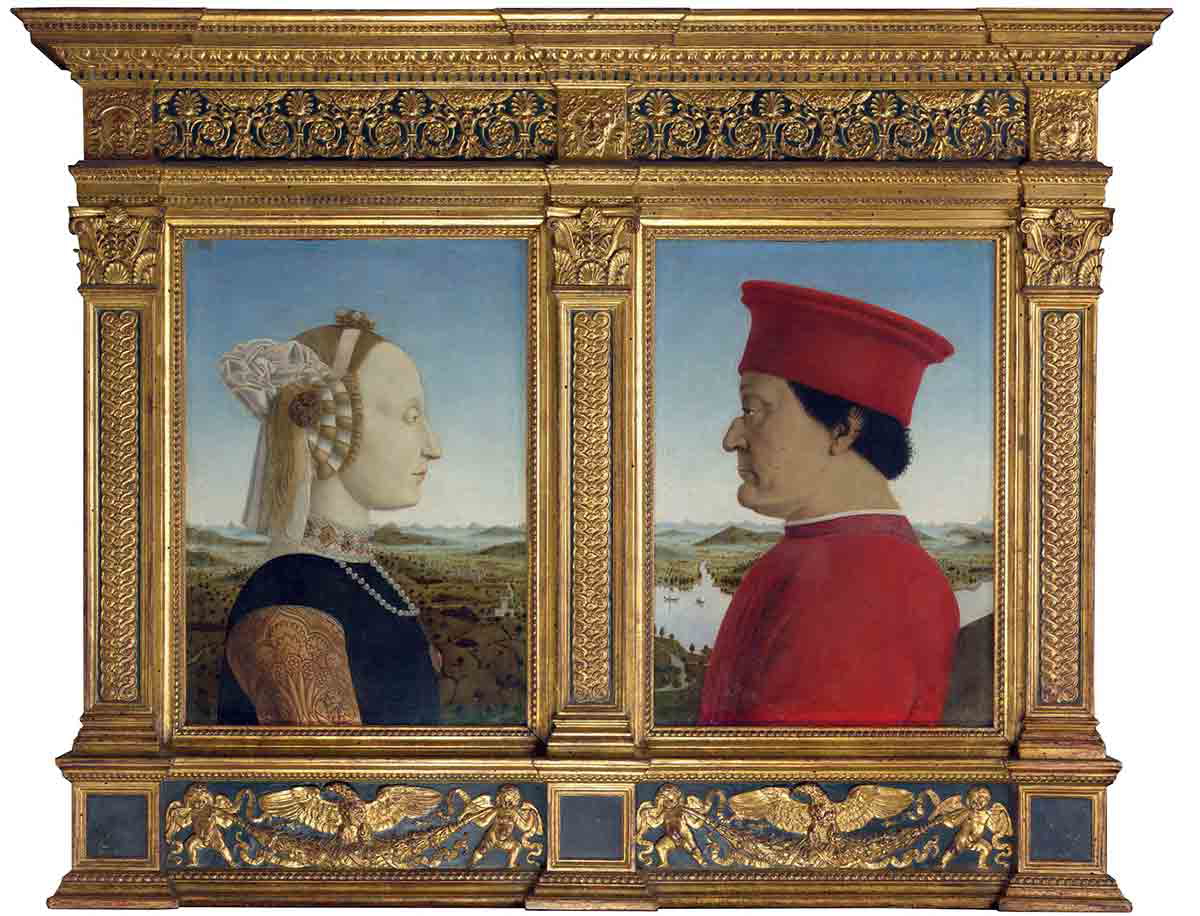

In the Netherlands and France, the diptych was almost exclusively used as a portable devotional object. However, in various city-states and regions of Italy, its purpose was to celebrate status and political achievements. Perhaps the most famous of these pairs of paintings is that of Federico da Montefeltro and his wife, Battista Sforza. Painted by Piero della Francesca, a close friend of the couple, its composition harks back to the traditional 14th-century portrait medals, with the subjects facing one another in profile.

The faces of the two subjects bear no expression. They are represented as nobles ruling over the rolling hills of the Marches, pictured in the background. Federico became Duke of Urbino two years after the portrait was painted. It is believed that, by this time, Battista had died. It has been suggested that the painting was commissioned either by Federico to celebrate his wife or by Lorenzo de Medici as a gift in honor of the couple.

The rear of the panels is redolent of the style of a Roman triumphal procession. This adds further to the idea that Lorenzo de Medici commissioned the work. In 1472, Federico achieved a significant success at Volterra as a condottieri fighting on behalf of the Medici. The Latin inscription refers to the magnificent triumph of the famous leader, whereas Battista’s side emphasises her virtues as a good and faithful wife.

Diptychs: Where Private Devotion Meets Wealth and Status

Throughout the late Medieval period and the Renaissance across Europe, the diptych served a specific purpose for those who could afford to commission one. Whereas portraits or devotional artworks were ordinarily displayed on the walls of private homes and religious establishments, the diptych could be tailored to the patron’s requirements and taken on their travels to serve as a personal shrine.

Generally smaller and more focused in its subject matter, the diptych provided the wealthy and those of high status a way to show their wealth as they travelled—they could afford to have a portable masterpiece in their luggage. In the case of Federico da Montefeltro, the diptych seemed to have been a gift from a grateful leader. It was a status symbol, confirmation of his prowess on the battlefield, and a gracious recognition of a cherished wife. Unlike their bigger brother, the triptych, the diptych was personal. It reflected the desires, beliefs, and achievements of an individual. Thankfully, the passage of time has allowed a glimpse into their world.