Ivory sculpture, carved from elephant tusk or its substitutes, has been an enduring art form in cultures all over the world, from the ancient Near East to Japan to Sub-Saharan Africa. It was particularly valued in the classical Roman world and its descendants, including the Byzantine Empire, Christian Europe, and the Islamic Middle East. With the widespread fashion for medieval artworks made of ivory, production of these small-scale sculptures depended largely on trade routes and relationships.

Ivory as a Medium in Medieval Artworks

Smooth, dense, and durable, elephant tusk is a good medium for fine, detailed carving. The most prized ivory came from African elephants, whose tusks are longer and better-suited to sculpture than those of Indian elephants. Europe has no native elephants at all and had to import all its ivory. Therefore, the geopolitics of trade routes played a big role in medieval ivory production.

Whoever controlled trade routes in the Middle East had abundant access to the ivory sourced from deep within Africa. This was an advantage for the Roman Empire, the Islamic world, and the Byzantine Empire in its earlier centuries. However, Christian Europe’s ivory supplies varied according to its ever-changing relationship with Islamic North Africa. Except for about a century during the Gothic period, ivory was relatively scarce to Europeans.

In northern Europe, walrus ivory (morse) was a common and more abundant substitute. Although broadly similar to elephant ivory, morse has a more yellow color as opposed to elephant ivory’s pure white. Morse also has a slightly different texture that does not facilitate such fine and sharp details. Accordingly, it was typically used for less-prestigious objects, while the supply of elephant ivory was saved for important religious works. For example, the famous Lewis Chessmen are carved from walrus ivory.

Occasionally, other types of animal bone and teeth were used as well. Although all might be called ivory colloquially, the word should be reserved for elephant ivory unless otherwise specified. European cultures with a taste for ivory carving that did not have the supplies to produce it, such as the Carolingian and Ottonian dynasties, sometimes also reused ivory by shaving down existing pieces and then re-carving them in lower relief.

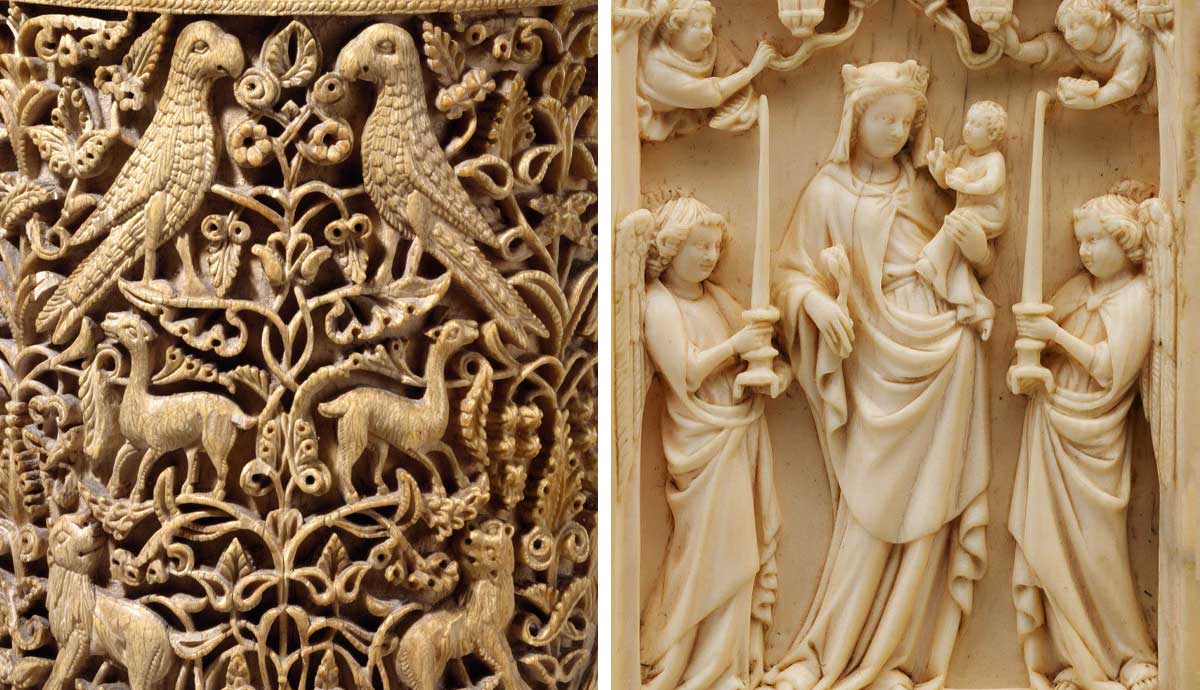

From about 1230 to 1330 CE, however, elephant ivory became accessible enough in northern Europe for a tradition of secular ivory carving to flourish, particularly in Paris. The Byzantine Empire produced both sacred and secular ivories, often following Roman precedents, while in the Islamic world, ivories were typically elite secular objects.

Carving Medieval Sculpture in Ivory

The majority of medieval sculptures in ivory were carved in relief on flat-backed pieces of ivory, though many fully rounded pieces also exist. Such sculptures may appear in higher or lower relief, sometimes even cut all the way through in places. Unlike medieval sculpture in stone, such as that on church portals, medieval artworks in ivory were not usually painted all over.

Particularly in Europe, ivory was too precious and its pure white finish too highly valued to cover up, though selected areas might be highlighted through paint or gilding. Ivory objects might also be inlaid with colored glass or semi-precious stones, particularly to create figures’ eyes, or appear alongside enamels and jewels as part of a larger composite object. Where it did occur, painting and gilding usually do not survive well on medieval sculptures in ivory.

By necessity, ivory objects are relatively small. Although elephant tusks can be quite large, their long, curved shape restricts the possible dimensions for a single piece of solid ivory. Additionally, the interior core is not suitable for carving. Larger objects could, however, be made from a series of smaller ivory plaques with relief-carved designs. Such sets of plaques have often been split up in museums collections all over the world, sometimes without any record of the object they once adorned.

A set of rectangular ivory plaques make up the exterior cladding of the 6th-century Throne of Maximian, a Byzantine-made decorative throne for the Bishop of Ravenna, Italy. While a now-scattered set of Ottonian ivory plaques called the Magdeburg Ivories, named after their German place of origin, once decorated a still-unidentified church furnishing. Ivory plaques were also used to make religious diptychs and triptychs, as well as to form lidded boxes called caskets.

The Many Functions of Ivory Plaques

Ivory diptychs come out of the Roman tradition of consular diptychs. Consular diptychs, pairs of ivory plaques hinged together like book covers, were essentially ancient notebooks. Low-relief sculpture decorated the outside, and wax tablets for writing appeared on the inside. Something like party favors, consular diptychs were gifts that Imperial politicians gave to high-status supporters upon attaining the rank of consul. Some Byzantine politicians continued the tradition of consular diptychs, but many such panels were eventually scraped down and re-carved. Classical-style diptych panels also frequently found new life as part of luxury book covers, called treasure bindings. Such panels might have been re-carved for this purpose or sometimes they were simply reused as they were.

With similar forms but different functions, sacred diptychs and triptychs (the same thing, but with three panels) appear in both the western European and Byzantine worlds as instruments of private prayer. The hinged two or three-panel shape parallels church altarpieces, only on a smaller scale for use at home. Already popular as Byzantine icons, this tradition took off in western Europe during the Gothic period, when elephant ivory was plentiful enough for private patrons to commission such works. These diptychs and triptychs usually portrayed scenes like the Crucifixion and figures like the Virgin Mary and Christ Child set in Gothic-style architectural frames. For such small objects, these devotional panels could be surprisingly detailed and packed with imagery.

Three-Dimensional Sculpture

Ivory was also used for freestanding religious sculpture, particularly statuettes of the Virgin Mary with the Christ child. Additionally, ivory figures of Christ on the cross frequently hang on larger crucifixes made in ivory or another material. Associations between elephant ivory’s white color and the idea of purity made ivory a fitting medium for images of Christ and Mary. It’s no coincidence that these figures often take on something of the curved form of an elephant tusk. This feature is particularly noticeable in the traditional pose of standing ivory sculptures of the Virgin Mary. Called “Gothic sway”, and it may have come about in part to accommodate the curve of the tusk in slightly taller sculptures. Since medieval sculptors tended to work on ivories as well as other media, we see Gothic sway in wooden and stone sculptures of the period as well.

Secular Ivories

Other small-scale ivory medieval artworks popular in Europe, Byzantium, and the Islamic lands included caskets, pyxides, combs, mirror backs, knife handles, and game pieces, among other objects. Caskets are small, rectangular boxes with hinged lids, and they were popular luxury items throughout the classical and medieval worlds. They consisted of separate plaques joined together and sometimes mounted on a wooden core. In ivory-carving centers of the Byzantine Empire, ivory caskets could be mass-produced, with different plaques of standard sizes available for patrons to choose from. Meanwhile, a pyxis (pyxides in the plural) is a cylindrical container with a lid. Unlike the casket, the walls of the pyxis were made from a single cylinder of ivory with an added base and lid. Both caskets and pyxides were typically covered in relief-carved imagery.

Generally, caskets and pyxides were luxury secular objects used to hold things like jewelry, perfumes, cosmetics. Accordingly, they were decorated with secular motifs. Themes of love and courtship were popular, since these medieval artworks frequently functioned as courtship or marriage gifts for both men and women. Western European examples commonly depict scenes from chivalric romance literature, like the Roman de la Rose and tales of King Arthur. In Byzantium, scenes from classical literature and mythology were popular. Islamic examples, including those from Al-Andalus (Islamic Spain) and Islamic-influenced Sicily, frequently depicted scenes of princely leisure, such as hunting and music-making in lush garden settings, as well as animals carved in deep relief.

Because they were generally not religious objects, Islamic ivories frequently depicted figurative subject matter. In all cases, medieval sculpture in ivory used similar styles and motifs as other artworks from the same time and place, such as manuscript painting, stone sculpture, and frescos or mosaics.

The Later Lives of Medieval Artworks in Ivory

Despite their original secular contexts, both caskets and pyxides from all over the medieval world could easily find themselves performing sacred functions later in life. Since Byzantine and Islamic medieval artwork was considered the height of luxury, Western European Christians who acquired these objects put them to use as reliquaries and containers for the consecrated Eucharistic bread and wine. Even the presence of Kufic (a type of Arabic) script on many Islamic objects did not disqualify them as potential Christian reliquaries. Just like gold and jewels, ivory was a highly-coveted material in the Middle Ages — sometimes sacred, but always luxurious. That is why many classical, Byzantine, and Islamic ivory carvings live today in European cathedral treasuries. They have often been modified and combined with other precious objects with diverse times and places of origin.

Ivory carving was not exclusive to ancient or medieval artwork. It enjoyed periods of popularity right up through the Art Deco sculptures of the early-20th century. Today, legitimate concerns about animal welfare have put an end to the ivory carving tradition. Even the market for historical ivories is now severely regulated. However, medieval ivory sculptures are still highly valued and visible in museum collections throughout the world.