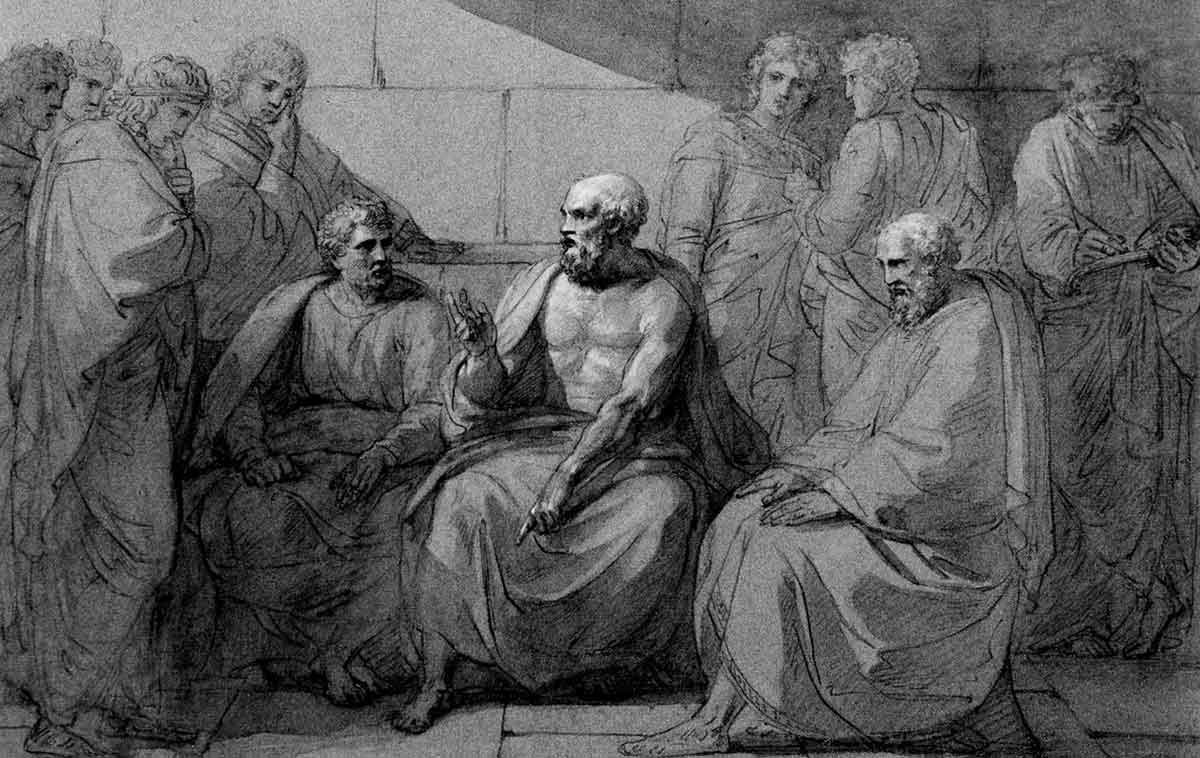

The Ancient Greek philosopher Socrates described himself as a gadfly. He was the gadfly, and the Athenians were the horse. Socrates’ job was to criticize and provoke his fellow Athenians into action. He did this by asking questions. Lots of questions. And it is this critical questioning, known as the Socratic Method, that has become the foundation of philosophy. In this article, we will look at the context Socrates was working in, what the Socratic Method is, and move on to some of its applications in philosophy and education.

Athens and the Thirty Tyrants

In a bloody eight months between 404 and 403 BCE, Athens was ruled by a group of men that came to be known as the “Thirty Tyrants.” The Spartans, who were victorious in the Peloponnesian War, installed the Tyrants as oligarchic rulers of Athens. Their attempts to exert control and crush Athenian democracy led to a rebellion and the reinstitution of democracy.

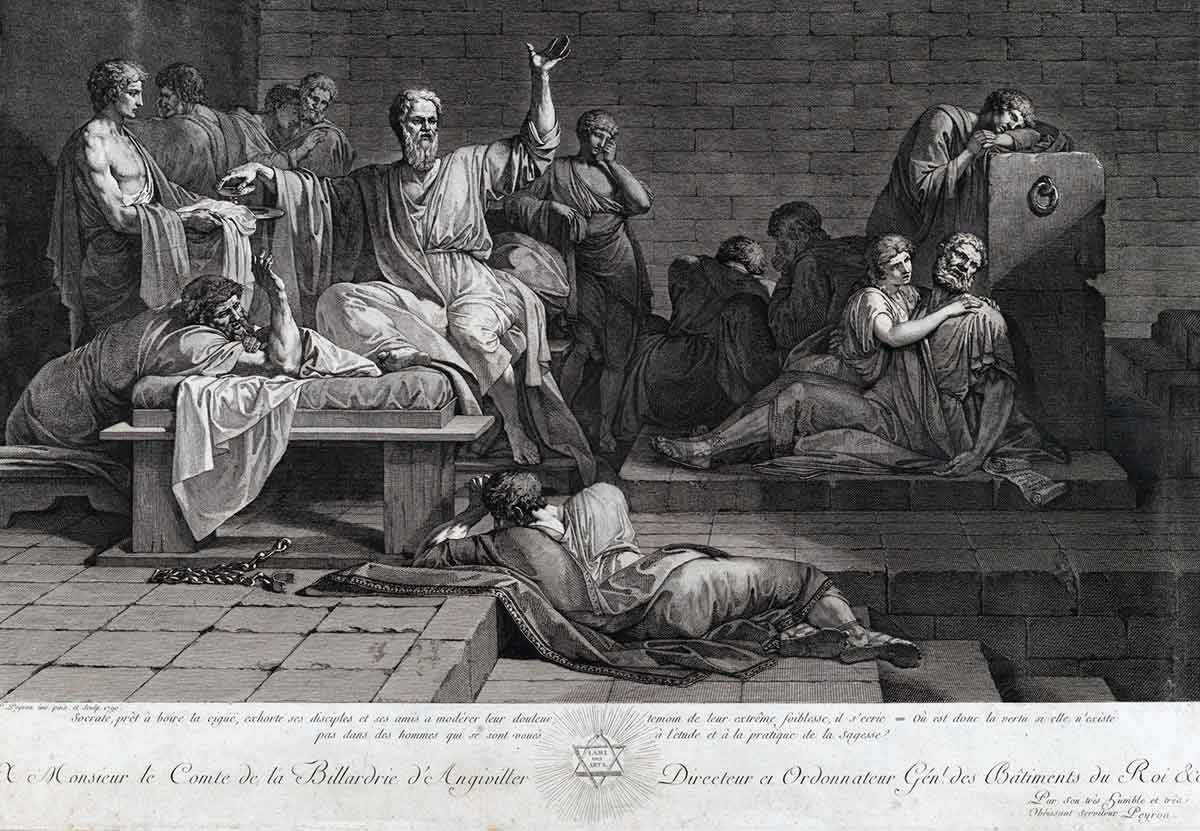

Socrates was a soldier in the Peloponnesian war, had a run-in with the Thirty, and was active in challenging the people of Athens in the period afterwards. So much so that the democratic rulers of Athens charged him with impiety and corrupting the youth and sentenced him to death in 399 BCE.

Plato recounts Socrates’ trial in the Apology. Here Socrates lays out his life’s mission. He wanted to show the citizens of Athens that wisdom, truth and improvement of the soul were of greater value than money or reputation. Socrates saw himself as a teacher and he had a method for teaching:

“I interrogate and examine and cross-examine him, and if I think that he has no virtue, but only says that he has, I reproach him with undervaluing the greater, and overvaluing the less.”

This can be summed up as asking questions of a person’s beliefs and expecting good reasons. Socrates sought wisdom, so he thought people ought to be able to give good reasons for what they believed was true.

The philosopher Martha Nussbaum argues that in this way, Socrates was defending democracy. For citizens to function in a democracy they must think for themselves, have reasons for their beliefs, and be able to articulate them to other people. Democracy requires that you do not accept what you are told as true, wise, or correct. You decide for yourself.

The Unexamined Life

Arguably the most famous Socratic phrase is “The unexamined life is not worth living,” which is also recorded in Plato’s Apology. This captures the heart of what Socrates was doing with his philosophy.

In his defence speech, Socrates explains that in searching for wisdom, he wandered around Athens talking with different people. He does this in an attempt to disprove the claim from the Delphic Oracle that there was no person wiser than Socrates.

He talks first with politicians, then with poets, and finally with the artisans. In every instance, he fails to find someone who has examined their life and can adequately justify their beliefs. Socrates realized that whereas other people think they are wise, but really are not, he himself was only wise because he knew his own ignorance.

Socrates was not interested in speculating about the physical world, as some of the pre-Socratic philosophers had done. He was interested in how people should live. His life was a continual quest for truth and wisdom. This focus on examining life meant that Socrates wanted to learn about virtue or “arete.”

“Arete” has several meanings: the closest translation is perhaps “excellence.” In discussing virtue, Socrates wanted to know what it meant to be an excellent person. He examined the virtues of courage, justice, temperance, and piety—qualities of character that are important in everyday life. Socrates reasoned that if you didn’t know what the virtues were or what they meant, it wasn’t possible to live a life with “arete.”

The Socratic Method

The method Socrates used for understanding virtue and examining life was asking questions. He wanted to challenge people to think for themselves and not accept dogmatism.

Examining life requires introspection, reflection, and what we now call critical thinking. Socrates used questions to prompt people to do just that, like a gadfly’s bite spurs a horse.

Socrates’ questioning followed a typical pattern, and the way his disciples Plato and Xenophon lay out the conversations in a dialogue form makes the reasoning easy to follow. The back and forth between Socrates and his interlocutor in a dialogue is why this method has come to be called dialectical.

Most dialogues center on a single topic and Socrates proposes the topic by asking for a definition, “What is X?” (where X is usually a virtue). His partner suggests a definition. Then Socrates proceeds to ask questions, searching for a single feature shared by all examples of that virtue.

The Socratic Method works largely on refutation. Socrates typically shows that his partner’s definition of said virtue is inconsistent with other beliefs. By asking a series of follow-up questions, he draws out contradictions, finds holes in knowledge or reasoning, and replaces a confidence in knowledge with an awareness of ignorance.

| The Socratic Method in a nutshell | |

|---|---|

| Step | What You Do |

| 1) The Claim | Clearly state the thesis. |

| 2) Clarify Terms | Define the key terms. |

| 3) Probe with Cases | Test the claim with examples that fit and examples that do not fit. |

| 4) Refutation (Elenchus) | Make the inconsistency explicit. |

| 5) Revise or Suspend (Aporia) | Arrive at a clearer claim—or an honest pause for reflection. |

Avoiding Dogmatism

In Plato’s Socratic dialogues, a definite answer to Socrates’ starting question is not always reached. This might seem like a cop-out, but it was in line with how Socrates worked. He claimed he had no knowledge, instead he had a skill for helping other people interrogate their beliefs and give birth to true insight.

Knowing that your beliefs are incorrect or inconsistent is the first step on the path to deeper understanding. As is an awareness of the limits of your understanding.

Socrates didn’t want to teach people directly as the Sophists did or give them answers, because he knew thinking for oneself was more important. This is a vital point, and a major reason why the Socratic Method is still relevant today in education and philosophy.

Dogmatism involves accepting dominant ideas and receiving knowledge from authority figures. It is passive and only requires memorization.

By contrast, the Socratic Method enables someone to discover knowledge and wisdom through their own thinking. It is an active, creative process, and it is the only way to free the mind from dogmatic belief.

People rarely, if ever, change their minds through direct confrontation i.e. being told that they are wrong. But when their thoughts are stimulated by the challenge of answering questions, they can free themselves from their erroneous ideas.

This makes the Socratic Method very powerful.

Limits of the Socratic Method

Aristotle pointed out that the Socratic Method was a form of inductive reasoning. Socrates attempted to work from specific instances of a virtue to reach a general conclusion about that virtue. Socrates did not think that virtues were relative. He thought they were absolute, applied to everyone, and in knowing right from wrong all people could learn to live with excellence.

Aristotle developed inductive reasoning beyond the moral realm, and Francis Bacon later used it as the basis for the scientific method. As opposed to deductive reasoning, inductive reasoning can never yield definite answers.

There are other limits to the Socratic Method. If it leads you to mere linguistic definitions, it is hard to see how this can yield the kind of moral knowledge that Socrates hoped to gain. Instead, we want our moral knowledge to be the basis for action in how we live.

The Socratic Method is good for critically assessing and clarifying existing beliefs and assumptions. It is not so good for uncovering completely new knowledge, especially of the empirical kind. This makes it better for moral reasoning and critical thinking than for doing science.

Cultivating Good Citizens

As mentioned earlier, Socrates can be seen as a defender of democracy. And while he never officially became a politician, he did try to influence the politics of Athens.

In Athens, almost all governmental posts, including military generals, were decided through voting. According to Xenophon, in one dialogue Socrates talks with a young man who wants to be elected a general. In his usual manner, Socrates highlights that the man does not have the knowledge required to effectively carry out the post he is applying for.

This dialogue shows a different, more practical Socrates. Instead of only being concerned with moral virtue, he believed that people should have the right skills, knowledge, and expertise to do the jobs of government. Democracy was more than a popularity contest.

There is a strong connection between the Socratic Method and education, which was clear even in Socrates’ day. At his trial, Socrates complained that Aristophanes’ play The Clouds had unfairly characterized Socrates and his methods.

At the heart of Aristophanes’ critique was the clash between a “traditional” and a “progressive” education. In a traditional education, a student was expected to memorize, learn, and follow the traditional way of doing things, thus ensuring stability.

But a “progressive” education was embodied in the Socratic Method of questioning. It meant thinking for yourself and not accepting a belief because it was “traditional.” This questioning of established authority was considered disruptive in Ancient Athens. But Socrates believed it was essential for a healthy democracy.

The Best Way to Live a Good Life

A liberal arts education is called liberal because it is focused on freeing the mind. The legacy of the Socratic Method is to apply critical thinking and questioning to the issues of everyday life. In this way, education can give students the skills, knowledge, and wherewithal to participate in society, and fulfill their roles as free, democratic citizens.

We can’t expect to make positive progress without questioning the assumptions on which our beliefs are built, finding the contradictions, and discovering the gaps in our knowledge. This requires both humility and a willingness to learn.

In continuing the Socratic quest for living a good life, the method of Socrates arguably remains the best way to do that.