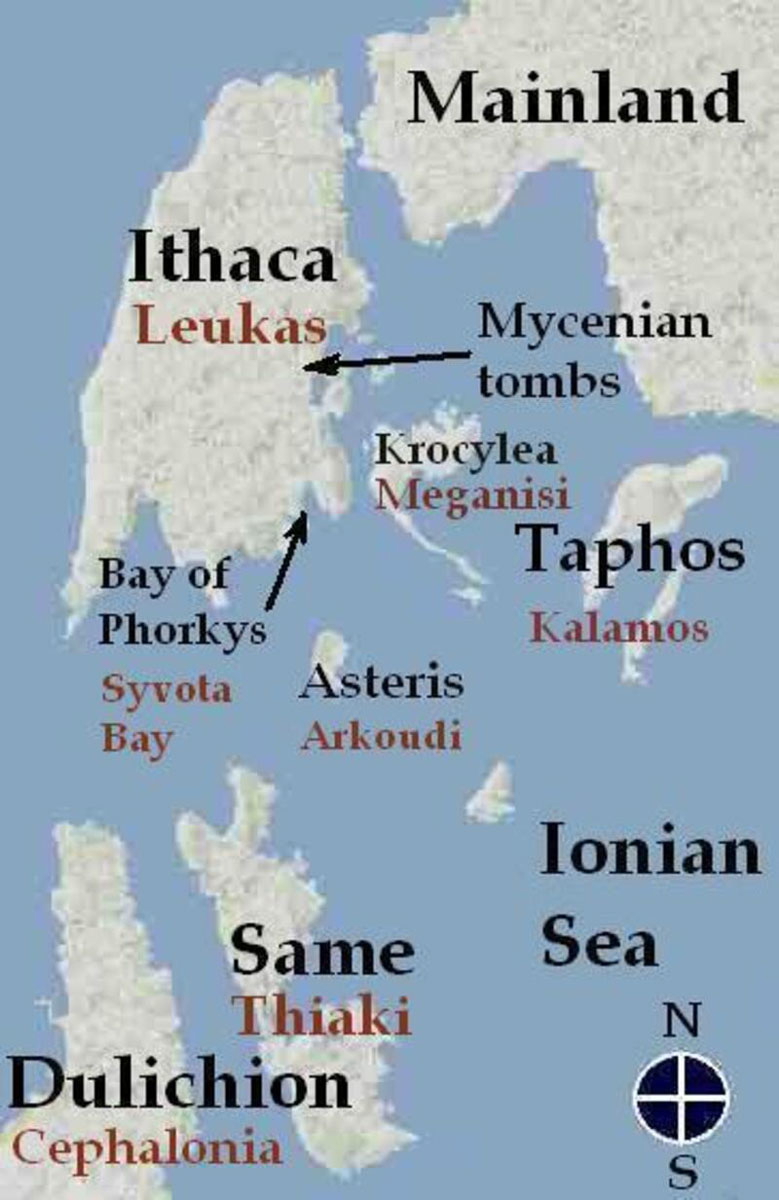

Homer’s Odyssey tells the story of Odysseus, one of the Greek commanders in the Trojan War, attempting to get home. The home in question is the island of Ithaca, where Odysseus ruled as king. Traditionally, this has been identified as the modern island known by the same name. This is in the Ionian Sea, off western Greece, just off the north-eastern coast of the island of Cephalonia. However, some scholars have argued that another location would fit Homer’s description better. What does the evidence really show?

Problems With the Identification of the Island of Ithaca

We know that the modern-day Ithaca was identified as Odysseus’ Ithaca in the ancient period. There are various pieces of evidence supporting this statement. For example, many ancient coins that archaeologists have discovered on Ithaca depict Odysseus, showing that he was associated with that island. Furthermore, an inscription shows that Odysseus was worshiped as a mythological hero on that island from at least as early as the 3rd century BCE. Strabo, an ancient geographer, also made this identification clear.

However, there are some apparent problems with this identification. First, Homer describes Odysseus’ Ithaca as “low-lying.” This seems to conflict with the reality of modern-day Ithaca, which is mountainous. Furthermore, Homer refers to Ithaca in the following way:

“Around it many islands lie very close to one another, Doulichion, Same, and wooded Zacynthus. It lies low on the sea, farthest off toward the gloom, with the others off toward sun and dawn.”

This suggests that Odysseus’ Ithaca was furthest to the west, or possibly to the north, of its island group, which the traditional Ithaca is not.

Alternative Identifications of Odysseus’ Island of Ithaca

Based on these problems, various alternative sites have been suggested for the true site of Homer’s Ithaca. One suggestion is Cephalonia. This is to the west of today’s Ithaca, and there are no other islands in the Ionian Sea immediately to the west of it. This, arguably, would match what Homer wrote about the location of Odysseus’ Ithaca relative to the other nearby islands.

Another popular suggestion is that Homer’s Ithaca was actually Lefkada. This is the major island to the north of Cephalonia and today’s Ithaca. One line of reasoning that has been used to support this theory is the fact that the description of Ithaca as “low-lying,” or lying “low on the sea,” has been translated another way by some scholars. This alternative reading states that Odysseus’ Ithaca was close to the mainland, which Lefkada certainly is. Furthermore, it is the furthest north of the four main islands in that area (Lefkada, Ithaca, Cephalonia, and Zakynthos).

The Forgotten Impact of Tim Severin’s Research

Something which has been almost entirely overlooked in discussions of this issue is how the research of historian and explorer Tim Severin has greatly clarified the matter. He investigated Odysseus’ route home from Troy as described by Homer’s Odyssey. In contrast to the traditional view that Odysseus traveled all around the Mediterranean, Severin took a more realistic view. Based on the assumption that Odysseus was actually attempting to get home, he concluded that he maintained his position when being blown off course while rounding Cape Maleas much more than other commentators had granted. According to Severin’s reconstruction, most of the journey described in the Odyssey took place right around the coast of Greece itself. For example, the land of the Laestrygonians, with their remarkable circular harbor, was identified as Mezapos Bay on western Greece.

This proposed reconstruction—which has much to recommend it—is very useful for determining where Homer’s Ithaca was. This is because this route has Odysseus weave through the Ionian Islands themselves, making it clear where Ithaca was.

The Route South Towards Ithaca

According to Severin’s reconstructed route of the Odyssey, the Acheron River, where Odysseus descended to the Underworld, is the Acheron River in Epirus, western Greece. This same identification was made in ancient times. Circe’s island, Aeaea, was identified by Severin as Paxos, not far from the mainland. From Circe’s island, Odysseus is said to have traveled past the island of the sirens. After this, he reached a point where he had to choose between two routes. One would take him down a channel on which there was a danger of both sides (Scylla and Charybdis), while the other would take him past the dangerous Clashing Rocks.

As it happens, on a route southeast towards today’s Ithaca from Paxos, one would go past the small island of Antipaxos, which fits well as the island of the sirens. After this, one comes to Lefkada. At this point, any traveler on their way to today’s Ithaca would have to make a choice, just like Odysseus in the Odyssey.

On the one hand, they could go around Lefkada to the west. In the sea on this side of the island, there is a rock formation called Sesola. This large rock formation has a gap through the middle through which an ancient Greek ship could sail, with the imagined danger of the gap closing in. This is very much like Homer’s reference to the Clashing Rocks.

On the other hand, a traveler could go around Lefkada on the eastern side. While today there is a causeway blocking off the northern entrance, there was formerly a channel completely separating Lefkada from the mainland. On one side of this channel, near the northern entrance, there is a cave on the rock face above the water. This part of the mainland is called Mount Lamia, the lamia being a figure from Greek and Bulgarian mythology very similar to Homer’s Scylla. The mainland just north of the entrance to this channel between Lefkada and the mainland is even called Cape Skilla.

From the Island of Meganisi

Therefore, everything suggests that the northern tip of Lefkada marks the point where Odysseus had to choose between two different routes. One would take him past the Clashing Rocks, while the other would take him down a narrow channel with Scylla and Charybdis waiting for him. This appears to be a reference to the two different ways of going past Lefkada. After this, Odysseus reached the island of Thrinacia. Later, Homer explains that Odysseus was blown by a south wind back towards Charybdis from this island. This shows clearly that Thrinacia must have been south of the channel in which Charybdis was located.

In line with this, Severin identified Thrinacia as the island of Meganisi, which is immediately to the south of the channel separating Lefkada from the mainland. The shape of this island looks like a curved trident, matching the meaning of Thrinacia. Furthermore, this area was associated with sacred cattle, just like the Thrinacia of Homer’s Odyssey.

From the aforementioned evidence, Odysseus’ route from Circe’s island just off the coast by the Acheron River down to Thrinacia seems as certain as it can reasonably be. It appears to be a description of the route from Paxos, next to the real Acheron River, past Lefkada to the island of Meganisi. From here, Odysseus is shown to be very close to his destination of Ithaca. However, he is prevented from reaching it by a southern wind. Due to this wind blowing from the south, he has to remain on Thrinacia, waiting for the conditions to change. This makes it clear that Thrinacia was to the north of Homer’s Ithaca. This fits very well with today’s Ithaca, which is to the southwest of Meganisi.

On the other hand, if Odysseus had been trying to get to Cephalonia, then this route does not make sense. It would have been far more logical for him to have gone down the western side of Lefkada. It would have been a perfectly safe and logical route. He could have stayed close to the western coast of the island, the southernmost tip of which is close to the northernmost tip of Cephalonia.

The Real Location of Odysseus’ Ithaca

In conclusion, the true location of Homer’s Ithaca continues to be debated. Aside from the island traditionally identified as Ithaca and known by that name today, the two other prominent candidates are Cephalonia and Lefkada. However, if we accept Tim Severin’s proposed reconstruction of the route of the Odyssey, the true answer is clear. Homer apparently describes a journey from Paxos southeast towards Lefkada, at which point Odysseus chose to travel down the eastern side of the latter island. This channel between Lefkada and the mainland was the channel in which Odysseus faced Scylla and Charybdis. If we accept this proposed reconstruction, which is very compelling, then Lefkada obviously cannot have been Homer’s Ithaca.

Likewise, this proposed route strongly argues against Cephalonia as Odysseus’ true home. If Cephalonia had been Homer’s Ithaca, then Odysseus would logically have sailed down the western side of Lefkada, not the eastern side. Therefore, at least inasmuch as Tim Severin’s research is concerned, the traditional identification of Ithaca must be the correct one.