In 79 CE, the Roman cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum were destroyed by the powerful eruption of Mount Vesuvius. Up to 16,000 victims were buried under ash and rubble or suffocated from poisonous gases. Many of such bodies left silhouette-shaped cavities in compressed ash. Modern-era archaeologists filled those cavities with plaster to reconstruct the final moments of the victims and possibly learn something about their identities. Read on to learn more about the famous victims and survivors of Pompeii.

Pompeii Victims: How Were They Found?

The eruption of Mount Vesuvius is one of the most famous natural disasters in history. In October of 79 CE, the volcano near the Bay of Naples erupted and buried the cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum under layers of toxic fumes, ash, rubble, and pumice. The destruction of densely populated cities soon turned into legends. According to various evaluations, up to 16,000 people died in the days of the eruption, most of them instantly. There were many of those who managed to flee, yet they lost their families and loved ones in the ruins.

In the 19th century, large-scale excavations of lost cities took place. At the same time, archaeologists began to find the remains of those who did not make it to safety. In most cases, archaeologists found not bodies but body-shaped cavities in compressed ash and pumice. Inside those cavities, there were still fragments of bones.

The key step to preserving the remains of the victims was initiated by Italian archaeologist Giuseppe Fiorelli. While excavating the city, Fiorelli noticed the cavities and realized they were left by human and animal flesh that later decayed. To preserve the memory of the victims and at least some information around them, Fiorelli poured plaster into each discovered cavity. After it hardened, the cast was carefully removed, preserving the form of a victim’s body at the moment of their death.

1. The Pompeii Soldier: The Nineteenth-Century Legend

The famous Pompeii soldier was one of the most popular myths of the Romantic era. During the early 19th-century excavations, archaeologists discovered a skeleton of a man in full armor, preserved directly beneath the Pompeii city gates. Almost immediately, the discovery was turned into a legend. Historians assumed that the figure was the last city guard standing: in a city deranged by chaos, he never received an order to leave his post, and thus remained on guard until he was buried under the ashes. This half-imagined story soon became an inspiration for artists and painters. British artist Edward John Poynter painted the image of the faithful soldier, copying his stance from antique marble sculptures. The contrast between the fleeing crowd of citizens and the loyal guard standing still reflected the values of military obedience and duty, so important for Victorian-era culture.

Although the soldier’s story sounded romantic, most historians do not share this point of view. Most likely, the soldier followed a natural human impulse to escape and sought shelter under the city gate where he died. Still, the image of the soldier found its place even in the written oeuvre of Mark Twain. However, Twain made a bitter remark, suggesting that if the man had been American, he would have stayed at his post—but only because he would have been asleep.

2. Pliny the Elder

One of the most famous victims of the Pompeii catastrophe was the natural philosopher Pliny the Elder, best known for his Natural History encyclopedia. At the time of the Vesuvius eruption, he observed the natural phenomenon from afar. When the situation turned dire, he decided to launch a rescue mission. Apart from being a renowned philosopher and author, Pliny the Elder commanded a Roman naval base in the Bay of Naples. He sent the boats with soldiers to the Herculaneum shore, and, after receiving a message from his friends, stranded there, joined the mission as well. According to his nephew Pliny the Younger, the philosopher died suffocating from toxic fumes that descended upon the shore.

In 2020, archaeologists tested some of the remains found at the Herculaneum Bay and matched one of the skulls to the remaining information about Pliny, such as his age and ethnic origins. However, no one could say for sure that those remains belonged to the legendary philosopher.

3. The Herculaneum Soldier

Another victim possibly related to Pliny the Elder was a soldier found on the beach of Herculaneum. His armor demonstrated he belonged to an elite force known as the Praetorian Guard, normally tasked with guarding the Roman Emperors. These discoveries were made in 2015 when a group of researchers realized that their predecessors hardly ever connected the victims’ bodies to the artifacts found in their vicinity. The soldier’s belt was decorated with cherubs and lions, which indicated his affiliation with the guard. The soldier was most likely part of the rescue team sent by Pliny the Elder to evacuate the residents of the Herculaneum coast. Unfortunately, he did not make it, and it is still unclear if Pliny’s operation was at least partially successful.

4. Mother and Son?

Pompeii and Herculaneum are remarkable sites not only because of their historical significance but also due to the fact they were discovered so early in modern history. In a way, Pompeii was never truly lost, and the site of the tragedy was frequented by generations of locals, travelers, and researchers. However, the breakthrough in excavations happened in the 18th century when the research practices and theoretical frameworks of archaeology were still just developing. For that reason, the 18th- and 19th-century research was filled with assumptions, far-reaching conclusions, and sometimes even direct manipulation of data.

For instance, some of these proto-experts were known to scrape off traces of pigment from ancient Greek sculptures, believing they would look better white. Present-day Pompeii experts are in a way victims of their predecessors’ generation, as they have to deal with not only the artifacts of the city but also with the traces of the presence of countless other people after Pompeii turned to rubble.

The original body of research concerning Pompeii and Herculaneum is riddled with assumptions sometimes so deeply ingrained that for decades no one bothered to double-check the information. One of such cases was the famous discovery of two bodies—an adult and a child they were holding on their lap, presumably a mother wearing a golden bracelet and her son. The group of figures assumed to be a family were found in the so-called House of the Golden Bracelet in 1974. Only half a century later, in 2024, archaeologists made a DNA test and revealed that the mother was actually a man of African origin, and the child had no genetic or even ethical relation to him. Thus, to figure out the true identities of the Pompeii victims and the connections between them, we have to set aside assumptions, however convincing they might be, and rely on scientific data.

5. The Garden of Fugitives

One of the most famous sites that contained remains of the victims was the location known among archaeologists as The Garden of Fugitives. The space was initially a large vegetable garden with a covered space used for banquets and celebrations. In 1961, archaeologists found a group of bodies buried in the garden. Among them was the youngest found victim of the disaster, a 12-month-old girl, who was found next to a young couple, possibly her parents. Apart from humans, archaeologists found on the site the remains of dogs clinging to their owners and even freshly baked bread.

Pompeii Survivors: Pliny the Younger and His Mother

Despite the scale of the catastrophe, many Pompeii residents managed to evacuate on time. Pliny the Younger, the nephew and the student of another Pliny mentioned above was one of those who saved themselves from the disaster. In his letters, he recounted the days of the tragedy and even shared his research concerning the death of his uncle. At the time, Pliny the Younger and his mother were staying in a villa near Pompeii. His mother was the first to notice the strange cloud looming over the volcano. According to Pliny the Younger, who became an accomplished lawyer and author as well, his mother begged him to go alone, complaining about her poor health and weak body. Somehow, Pliny convinced her to go with him, and both of them managed to get to safety.

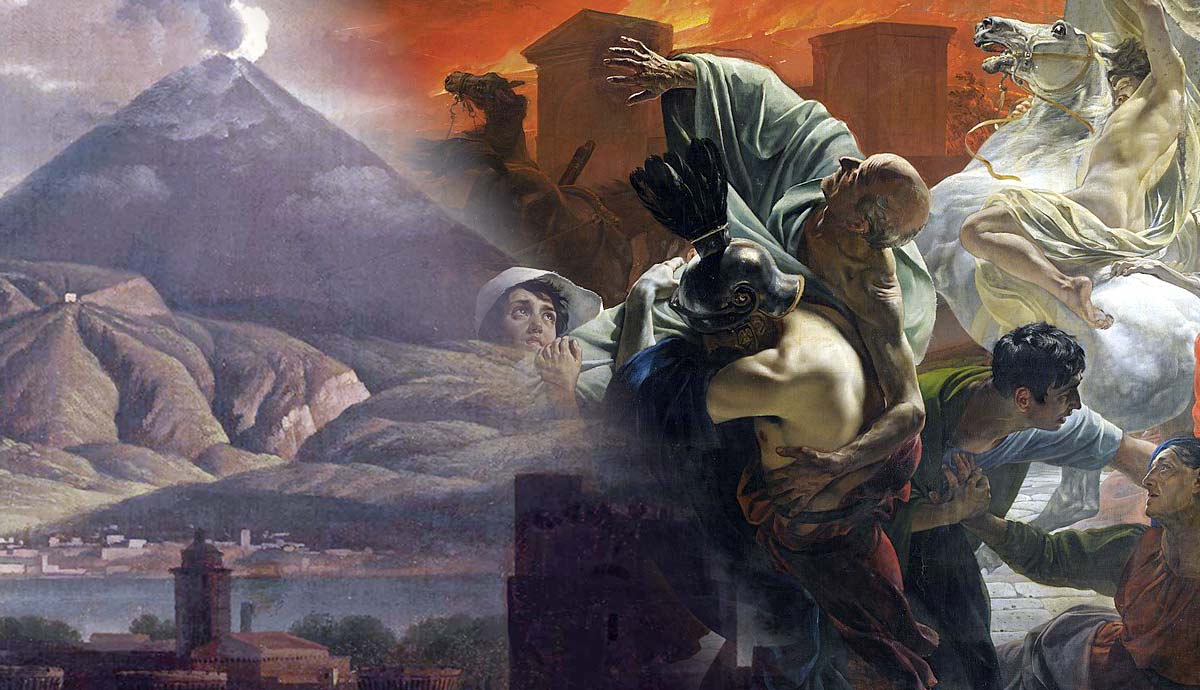

Pliny and his mother were among the most prominent characters in Karl Bryullov’s famous painting The Last Day of Pompeii. Bryullov was a Russian Romantic painter of German origin who visited Pompeii in 1823. Impressed by the remnants of the ancient city, he created a monumental work that featured both historical figures and characters inspired by the plaster casts of victims Bryullov saw in the city museum.