Epicurus was a hedonist who believed pleasure was the highest good. However, he also believed that pleasure was simply the absence of suffering. For him, humans should strive to attain a state of ataraxia or ‘untroubledness’. His philosophy aimed to overcome the four main worries that would trouble most humans. One of these was the fear of death. Epicurus thought that death was nothing to be afraid of, and in this article, we will see why.

Who Was Epicurus?

Epicurus was born on the Greek island of Samos in 341 BCE to Athenian parents Neocles and Chaerestrata. He moved to Athens in 323 BCE, aged eighteen. Alexander the Great died in the year, which had political ramifications for Athenians living in Samos. Epicurus’ father moved from the island to the city of Colophon, which stood on the site of the present-day town of Değirmendere on the Turkish coast.

Epicurus left Athens and joined his father, where he stayed for the next ten years studying philosophy. He then spent some time living on the Greek island of Lesbos and on the mainland in Lampsacus. In both these places, he continued his philosophical work and gathered followers. At around 307 BCE, his last move was back to Athens, where he remained for the rest of his life. He died at age seventy of complications resulting from stones in his urinary tract: an incredibly painful death but of interest since Epicurus claimed to have no fear of death or, indeed, of pain. More on this shortly.

While in Athens, Epicurus founded his famous school, ‘The Garden’. The name derives from the fact that the school used a garden as its meeting place. It was between two of the most famous schools in Athens, The Stoa and The Academy. The Stoa gave its name to the philosophical movement known as Stoicism. Zeno of Citium, the founder of Stoicism, taught there from 300 BCE. The Academy was a school set up by Plato in 387 BCE, where Aristotle studied for two decades. On the door of The Academy was a sign that read, “Let no one ignorant of geometry enter here.” On the door of The Garden, the sign read, “Stranger, here you will do well to tarry; here our highest good is pleasure.”

The Garden

Today, the word ‘epicurean’ often precedes other words such as ‘delights’ and is used to describe taking pleasure in the sensual enjoyment of food and drink. However, were you to visit The Garden, the food awaiting you would likely consist of little more than bread and water with perhaps a piece of cheese. Epicurus and his followers lived very simply. He only took wine medicinally to manage pain, and even then, it was diluted with water. Where, then, did this association between Epicureanism and sensual delights originate?

The confusion probably stems from a combination of misunderstanding and malicious gossip. Epicurus scandalized the Athenians by opening his school to women and slaves. We can contrast this with Plato’s Academy, which was theoretically open to the general public, but in practice, students were restricted to upper-class men. Due to sexist and classist attitudes at the time, as well as the age-old delight in prurient gossip, people speculated about what went on behind the walls of The Garden with these women and slaves.

In addition, much of the history of today’s ancient world was collated and curated by scholars connected to the Church. The dominant philosophy of Epicurus’ time was Platonism, and Epicureanism challenges this philosophy. From a Christian perspective, the philosophy of Plato is far more palatable than that of Epicurus. This is so much so that German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900) once suggested that Christianity is merely Platonism for the masses. We can see then that Christian scholars are unlikely to approach Epicureanism without some bias.

Despite the malicious gossip about the goings-on at The Garden, critics unanimously praise Epicurus’ character. As a man, he seems to have been very friendly, kind, and well-liked.

Epicurus’ Hedonism

Hedonism is the philosophical view that pleasure is the highest human good. Consider the sign outside The Garden: “the highest good is pleasure.” Put simply, a hedonist judges the best course of action on the basis of how much pleasure they anticipate being derived. However, as is always the case in philosophy, things are rarely simple! The Epicurean idea of pleasure is somewhat nuanced and perhaps a little unexpected.

Earlier, we saw that a visitor to The Garden might expect to be offered some bread or water rather than what we might (today) imagine being an ‘epicurean feast.’ For Epicurus, this simple meal provides the opportunity for pleasure. It is not too hard to imagine that, if one were absolutely starving, a hunk of dry bread and a cup of water to wash it down might be experienced as the greatest meal ever tasted. However, Epicurus goes further than this. He would claim that while a sumptuous feast would certainly be pleasurable, it would be no more pleasurable than some bread and cheese. The pleasures differ, but one is not more pleasurable than the other.

The explanation offered by Epicurus is that pleasure is the absence of suffering. So, in the case of the pleasure from eating, it must derive from the lessening and absence of the pain of hunger. Similarly, the pleasure of relaxing comes from easing the suffering of tiredness; the pleasure of a massage comes from the ease of muscle tension, and so on. If Epicurus is correct, the pleasure of a cheese sandwich can be neither greater nor lesser than a feast. For Epicureans, the ultimate goal for human beings is the attainment of ataraxia (the state of ‘untroubledness’).

Epicurus’ Antidote to Despair

Attaining a state of ataraxia might seem like a tall order. Most of us probably think that all human beings will always have something to be troubled about simply by the virtue of being human. Epicurus had what he thought was the answer. He called it the tetrapharmakos.

In ancient Greek, tetra refers to ‘four,’ and pharmakon means ‘drugs, poison or a spell’ (where we derived the word ‘pharmacy’). In Epicurus’ time, there was a medicine known as the tetrapharmakos that was used to treat ailments of the soul. It contained four ingredients: wax, pitch, resin, and animal fat. So, we can think of Epicurus’ tetrapharmakos as a kind of fourfold remedy and expect four things that will help us achieve ataraxia. The ‘four things’ are the four doctrines of Epicureanism. These are:

- Do not fear god.

- Do not worry about death.

- What is good is easy to get.

- What is terrible is easy to endure.

It is easily seen that these would concern human beings and prey upon their minds. Epicurus attempts to remove troubling concerns that might prevent a person from achieving ataraxia or a state of untroubledness.

1. Do Not Fear God

The Greek gods were seen as superpowerful beings who could cause terrible harm to humans. Accordingly, many people went out of their way to appease the gods and avoid offending them. The worry that a supernatural being might take umbrage with something one has or has not done is certainly troubling. Such a worry would be an obstacle to attaining ataraxia, the state of being untroubled.

Epicurus’ argument is simple. He agrees that the gods are powerful supernatural beings, indestructible and all but invulnerable. They also exist on a higher plane than mere human beings and in a state of bliss. All this being so, it is questionable that any of the gods would take the slightest interest in the activities of mortal beings. We can imagine the situation from our own perspective, looking down on the activities of, say, an ant. The tiny insect scurries around, attempting to do something or other known only to it. Perhaps it is looking for food to bring back to its nest or looking for a suitable location for a new nest. The point is we would not really care—the lives of individual ants, their cares and concerns, are trivial to us. The same would be true of the gods in relation to human beings.

Epicurus argued that gods should not be feared but used as role models to guide behavior. He said that people should attempt to emulate the happiness of the gods within the limits of the human condition.

2. Do Not Worry About Death

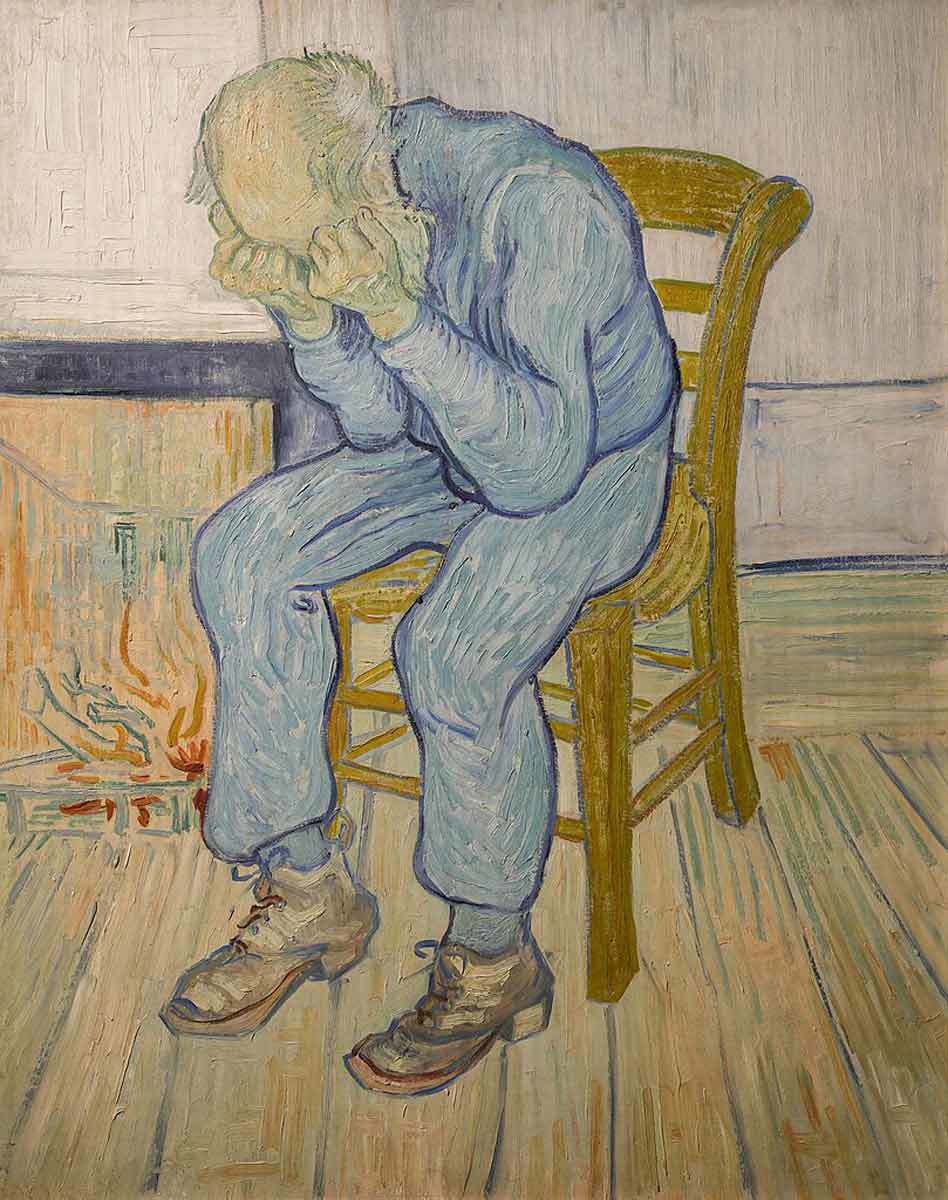

We come now to why Epicurus thought death was nothing. We have seen that Epicureans believe the greatest good for human beings is to achieve a state of ataraxia and be untroubled by anything. Fear of death must count as one of the more troubling fears that all human beings share. However, Epicurus thought that this fear did not really make sense and that death ought not be something that should worry us. This is because death is something that we never really experience, and after death, there can be no suffering. We remember the absence of suffering is, for Epicurus, ‘the good.’ Let us take a look at these ideas.

Firstly, since all humans are mortal, death is something that will come to all of us. However, unlike other experiences that we must go through simply by virtue of being alive, death is not something we will actually experience. When the time comes, we will pass from a state of being alive to death. Because we must be alive to experience something, and we are not alive when dead, the actual moment of death will not be experienced. Put simply, we will be alive, and then we will not be alive. Accordingly, the experience of death is something that will never ‘happen’ for us and so does not need to be feared.

Secondly, once we are dead, we will experience nothing at all. This means that we cannot experience suffering. The dead do not get hungry or feel tired, their bodies do not ache, and they never have worries about the future. If the good is the absence of suffering, then the bad must be the presence of suffering. Since there is no suffering after death, it cannot be bad and ought not be feared.

3. What Is Good Is Easy to Get

We have already seen what Epicurus might mean by the third doctrine. A simple meal is easy to get and provides as much pleasure as a grand feast (which would be much harder to put together). For Epicureans, ‘the good’ is pleasure, and pleasure is the absence of pain; therefore, anything that alleviates pain and suffering is ‘good.’ Because a person only needs the simplest things that will do the job—and simple things are simple to acquire—what is good is easy to get.

4. What Is Terrible Is Easy to Endure

While Epicurus’ thoughts on the gods, death, and the good might seem plausible to some, his claim that what is terrible is easy to endure is a far more difficult sell. Indeed, few philosophers today would go along with Epicurus here. Let us have a look at what he has to say.

Epicurus sorted physical pain into two kinds: heavy and light chronic. He then claimed that heavy pains are easily endured because they do not last very long. Chronic or regularly recurring pains, on the other hand, last longer but are much weaker in intensity and, therefore, are also easily endured. The point is not that pain is unpleasant but that the thought of future pains ought not to trouble a person too greatly because no matter which type might be coming, both are easily endured.

This view of pain seems more than a little implausible. However, it must be admitted that Epicurus would have been no stranger to pain. It was mentioned at the start of this essay that he died at age seventy from complications caused by stones blocking his urinary tract. The pain caused by this condition would have been intense.

In a letter written to a friend, Epicurus talks of the pain caused by his inability to urinate and of having violently painful dysentery. However, he also says that his recollections of previous philosophical contemplations counterbalance all of his sufferings! Diogenes Laërtius mentions this letter in his Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers, and opinion is divided over its authenticity; however, if it is genuine, then Epicurus’ endurance over terrible pain is truly remarkable.