Accusations of witchcraft weren’t exactly rare in the 15th century, but for the Woodville women, being clever, influential, and—heaven forbid—good-looking, seemed to seal the deal. Jacquetta of Luxembourg and her daughter Elizabeth Woodville learned that a little charisma and a good marriage could easily turn into “proof” of sorcery. From mysterious family legends of descent from a water goddess to claims of love spells gone “too right,” these stories of accusation and their fallout remind us how uncomfortable medieval society was with powerful women—and how quick they were to slap an “evil” label on anything they couldn’t control.

Witchcraft in the 1400s: When Independence Looked Suspiciously Like Sorcery

By the 1400s, a woman with opinions was about as welcome as a plague rat, especially if she held any influence or, heaven forbid, made decisions independently. If a royal woman wielded her instincts politically or even quietly defied the men around her, the accusation of “witch” lurked just around the corner.

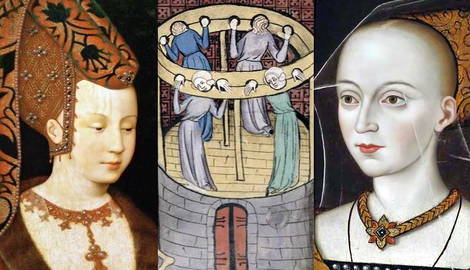

Jacquetta of Luxembourg and her daughter Elizabeth Woodville came to experience this firsthand. These women were a thorny pair for their time: Jacquetta, Duchess of Bedford, was from an old aristocratic family and Elizabeth, who later became queen of England, was uncommonly beautiful, strategically savvy, and stubbornly uninterested in staying in her lane. In the male-dominated world of politics and landholding, it is hardly a shock that whispers of witchcraft clung to them like ivy, planted by those who were jealous of their successes.

The 15th century was a brutal era for women who dared to take possession of the direction of their own lives or, worse, the direction of their children’s lives and countries. The Church and the Crown had a vested interest in making sure that royal power stayed where it belonged: firmly in the hands of legitimate high-born men. If a woman seemed just a bit too intelligent or her luck too golden, the gossip began. Because the medieval mind loved a good scapegoat, anything “off” about a woman could be pinned on the use of witchery. In Jacquetta and Elizabeth’s case, their connection to the legend of Melusine—a mythical water spirit who was half woman, half serpent—became the fodder for these whispered accusations.

Though Melusine had originally been a symbol of strength and a near-mythical right to rule in the Luxembourg bloodline, for their enemies, the tale became proof of their “unnatural” gifts.

Though an interesting case because of their connection to each other and their unusual marriages, Jaquetta and Elizabeth weren’t rarities. Women across royal courts were often viewed with suspicion if they dared to step beyond their prescribed roles. For these women, stepping out of bounds could be a fatal mistake. Even the suggestion of supernatural influence—true or not—was a tool to strip personal liberties and inheritances from women and, sometimes, their entire families.

The newly minted noblewoman Joan of Arc met her death following accusations of witchcraft, nearly four decades prior to those that would fall on Jacquetta. Joan died for her defiance of what was expected of her as a woman. Independence, it seemed, was the most suspicious trait of all.

For the Woodvilles and women like them, every public and private act of power had to be carefully calculated to avoid provoking suspicion. Marriages, alliances, and even the mere act of being able to bear many healthy children could brand them as a threat to good, innocent people. For Jacquetta and Elizabeth, navigating the often turning tides between warring factions was a matter of survival, where a single misstep could see their reputations burned at the stake, if not themselves.

Accusations Against Jacquetta

When Jacquetta of Luxembourg made the audacious decision to marry the dashing Richard Woodville for love (and without royal permission), it is safe to say she upset the social order. Having already been married to the Duke of Bedford, an English prince, and brother of King Henry V, Jacquetta’s match with a mere knight shocked everyone from the fashionable court to the commoners in the countryside.

Jacquetta must have known she was inviting scrutiny from those who saw darkness where there was probably only love. After all, why else would a duchess marry so far beneath her and feel the need to hide it from her sovereign? In addition, Jacquetta did the unthinkable. She went from being allied with the Lancastrians to the embrace of their bitter enemies, the Yorks.

Fast forward a few years, and Jacquetta’s high-profile family had only grown more influential. Her daughter Elizabeth married King Edward IV, catapulting the Woodville clan to the top of England’s power pyramid. In a kingdom where men with royal blood and battle scars still believed that kingship was theirs for the taking (and all were related and therefore all with claims to the crown), Jacquetta was dangerously visible—and so was her family. Enter the Duke of Gloucester, later Richard III, who saw Jacquetta as a convenient target to destabilize Edward IV’s reign and discredit the Woodvilles entirely.

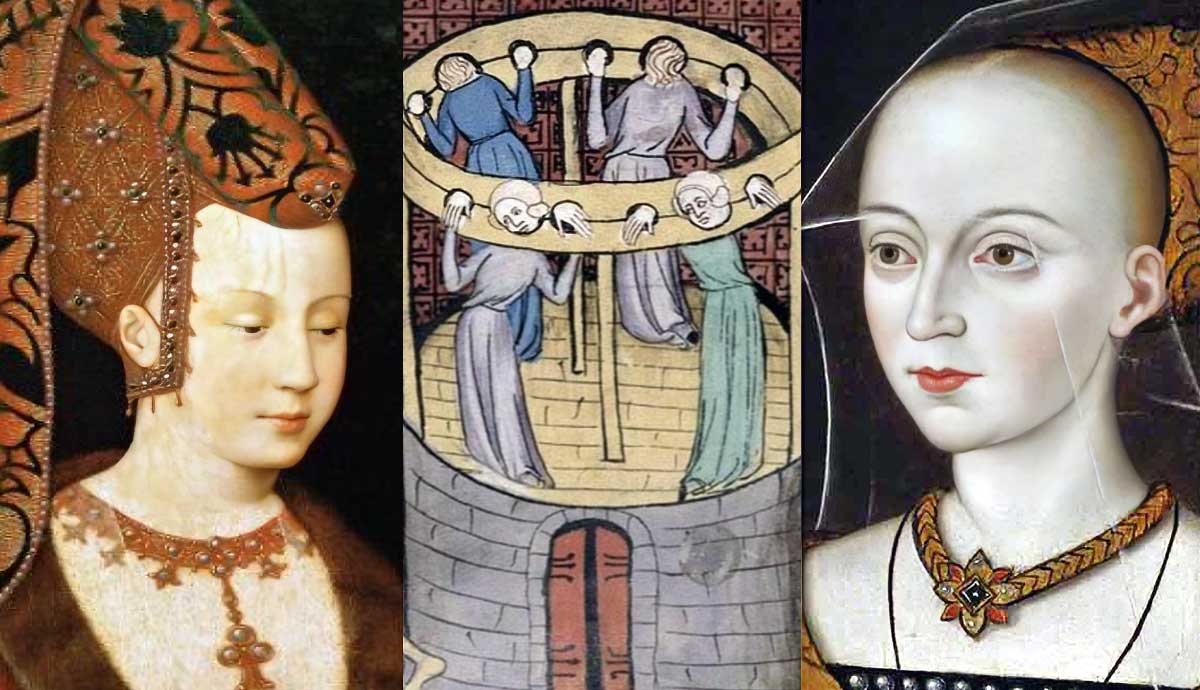

Richard convinced an associate to claim that he had proof that Jaqcuetta had used magic to influence her daughter’s match with his brother. Gloucester’s allies trotted out tales of Jacquetta’s supposed sorcery and presented a sensational piece of “proof”—voodoo dolls!

Yes, they actually claimed they’d found small metal effigies of King Edward and others among her belongings, conveniently implying she’d been dabbling in the dark arts to manipulate her family’s rise. Was this evidence credible? Hardly. In fact, it appears that this “evidence” was less about magic and more about male ambitions, with a dash of creative storytelling.

Richard and his supporters were all too willing to paint Jacquetta as a witch, banking on medieval minds being quick to jump to superstition when powerful women made unpredictable choices. To them, Jacquetta’s choice of her own husband, romanticized beauty, and her family’s ascent was dangerous enough to warrant drastic measures, like dragging her through a sham trial.

Jacquetta’s “trial” for witchcraft unraveled as quickly as it had been spun together. It turns out that accusing one of England’s most prominent women of casting spells requires more than wild rumors and a handful of dolls—especially when that woman is the mother-in-law to the king himself. Edward IV wasn’t about to stand by while his family was dragged through the mud, so he intervened to defend Jacquetta. Her innocence was ultimately confirmed, largely because her accusers couldn’t produce a shred of credible evidence that withstood the scrutiny of even a medieval court.

The whole case fell apart under closer inspection, and with Jacquetta acquitted, the so-called “evidence” was dismissed as nothing more than political theater. In clearing Jacquetta’s name, Edward IV didn’t just protect his mother-in-law—he sent a clear message that the Woodville family was not to be undermined so easily. As for Jacquetta, she’d survived the trial with her reputation—and her influence—intact, becoming one of the few women accused of witchcraft to walk away mostly unscathed.

Jacquetta would go on to give her Woodville husband 14 children. She lived a very full life, though not a magical one, before dying at 56 years old.

Accusations Against Elizabeth

When Elizabeth Woodville met Edward IV, she was no passive damsel hoping for mercy: she was a widow with two young sons, navigating a world that often cast women like her aside. Her first husband, Sir John Grey, had fought for the Lancastrians and died in battle, leaving her sons stripped of their inheritance. Elizabeth, known for both her beauty and her keen understanding of court politics, recognized the unique opportunity posed by Edward, a newly crowned king with a reputation for charm and impulsiveness.

According to contemporary accounts, Elizabeth set the stage for an encounter that would put her in Edward’s path, positioning herself under an oak tree. In this way, she knew how to best show off the right mix of vulnerability and allure in order to capture the young king’s attention. It worked. It worked better, perhaps, than Elizabeth could have foreseen.

Edward, supposedly struck by her beauty and her boldness, found himself compelled to help her—a desire that quickly transformed into a determination to make her his queen. He seemed to know just how jarring this romantic decision would be to his newfound reign. It didn’t stop either him or her, though it did influence their decision to marry and consummate said marriage covertly. Their swift, secret marriage in 1464 upended expectations and angered many in the court who believed a king’s marriage should be more politically advantageous, especially with the opportunity to strengthen ties to a foreign court.

Elizabeth’s rapid and unpredicted ascent was often regarded with suspicion by her detractors, who whispered of sorcery and seduction. In truth, however, Elizabeth’s “witchery” lay not in spells but in her unyielding confidence, her calculated moves, and her ability to turn adversity into opportunity—a combination as powerful, and as threatening to her enemies, as any supposed enchantment.

Their marriage didn’t stop with love at first sight, either. It was remarkably fruitful, producing a healthy string of ten heirs in rapid succession, a fact that Elizabeth’s detractors didn’t overlook. To her critics, it wasn’t just love or biology at work here—it was spellwork to keep her alluring and fecund. The whispers turned into accusations that she’d used dark arts to bewitch Edward and tie her bloodline to that of the ruling family.

Royal marriages were supposed to be pragmatic political unions, not passionate affairs with enough romance to produce a brood of healthy babies. Elizabeth defied that narrative at every turn, and her independence—and sway over her besotted husband—unsettled those who preferred their queens quietly obedient.

Unlike her mother Jacquetta, Elizabeth Woodville didn’t face an official trial for witchcraft. Instead, she was surrounded by a simmering stew of gossip, suspicion, and ill-meaning whispers that stayed mostly in the realm of shadowy speculation. While Jacquetta was forced into a high-stakes defense of her reputation (complete with alleged voodoo dolls), Elizabeth’s so-called “crimes” didn’t produce any physical evidence. Her enemies preferred the safer route of insinuation over outright accusations, especially given her influential position as a queen beloved of her husband.

Elizabeth, in the eyes of those rumormongers, was absolutely a witch. After all, she was a woman who had dared to secure her own future and children’s fortunes—without a male relative pulling the strings. That alone was enough to make her seem a little too fruitful, a little too flourishing, and a little too close to something otherworldly.

Other High-Ranking Women Accused of Witchery

Jacquetta and Elizabeth were hardly alone. Across cultures, empresses, duchesses, and wives of kings faced similar charges, and the pattern is unmistakable: a woman who dares to be more than subordinate suddenly has her virtue—and magical prowess—called into question. In fact, Jacquetta and Elizabeth were just two in a cross-cultural, location-defying line of women who would be accused of royal occultism.

400 years before Jacquetta would face similar accusations, Empress Meng (1073-1131) from China’s Song Dynasty would be banished from court over rumors of witchcraft. Meng was married to Emperor Zhezong, a match orchestrated by his powerful mother, Empress Dowager Gao. The emperor and Empress Meng reportedly never warmed to each other despite the Empress Dowager’s encouragement. When Meng’s young daughter contracted some disease, Meng was accused of sorcery, all for searching for a cure, and exiled to a Daoist nunnery—a swift removal from influence under the guise of a witch’s punishment.

Meng’s adoptive mother, who had tried to help her daughter and granddaughter, was executed for the crime of being an accessory to witchcraft, which was really just showing care and concern for a small child. Meng’s own exile was essentially an elegant off-ramp to prevent her from interfering in court, much like Jacquetta’s reputation was smeared by accusations of sorcery to sideline her influence.

Ironically, Meng’s banishment saved her life when the Jurchen invaders captured most of the royal family—a fortuitous twist that must have seemed a bit too lucky for her detractors. Empress Meng’s fall and survival make her a kindred spirit to Jacquetta, showing how witchcraft accusations often served as an excision from circles of influence.

Back in England, and closer to home for Jacquetta and Elizabeth, was Eleanor Cobham, Duchess of Gloucester, whose story echoes Elizabeth Woodville’s. Married to Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, the childless king’s only uncle, Eleanor found herself a heartbeat from the throne with her husband next in line. However, like many before, this was a contested succession. So, persistent rumors were invented that Eleanor was dabbling in astrology and consulting the notorious “Witch of Eye.”

Much like accusations against Jacquetta, those enemies of hers were busy claiming she was crafting wax dolls and plotting the king’s demise. Much like Elizabeth, whose match with Edward IV upset all hopes of a strategic royal marriage, Eleanor’s marriage posed a problem to those hungry for power. Much like Empress Meng, Eleanor’s co-conspirators met a swift and violent death, and she was banished to the Isle of Man. The moral: in a court where powerful men wanted you gone from the eyes of the people, accusations of witchcraft provided the perfect excuse.

Across cultures and centuries, the message was the same: women who strayed beyond domestic-only roles could expect retribution in the form of whispered suspicions and witch hunts. It was never about magic—it was about fear. Jacquetta, Elizabeth, and their fellow “witches” were simply too compelling, too influential, and too far from “obedient” for comfort.