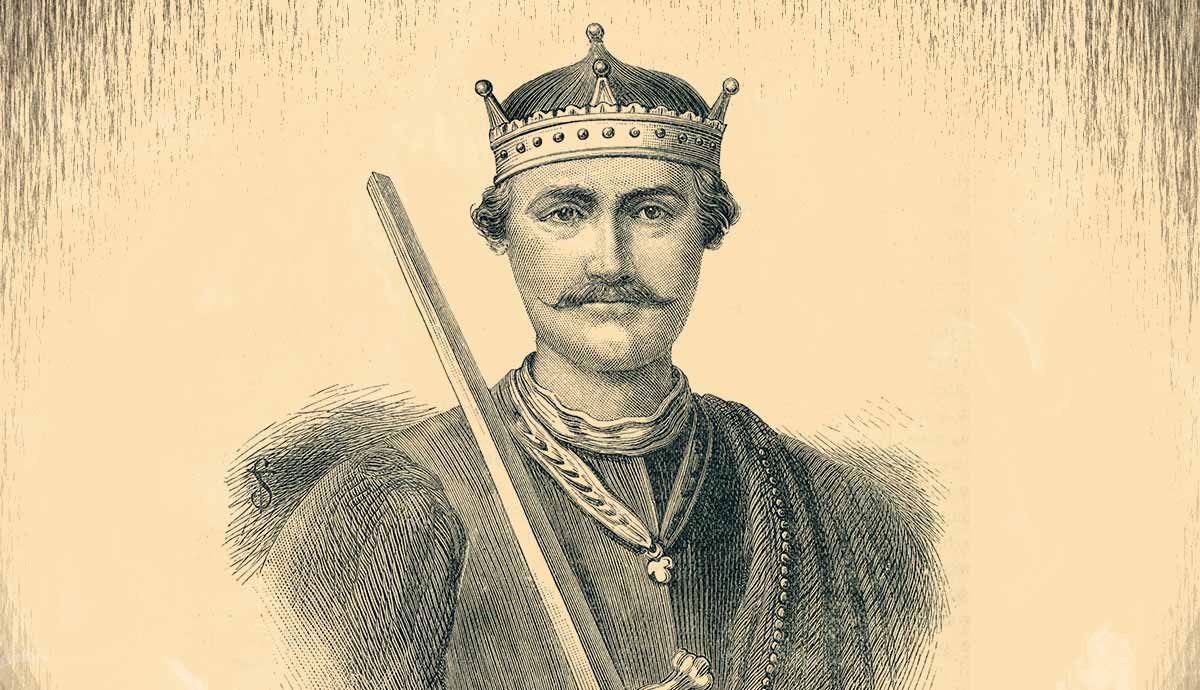

Without doubt, William the Conqueror is best known for his conquest of England in 1066. His decisive victory at the Battle of Hastings led to the Norman invasion and profoundly changed the face of England forever. But how did William become the Duke of Normandy, and what led to the decision to set his sights on England, and what factors ensured his success?

Early Life of the Duke of Normandy

Young William hailed from Normandy, a region in northwest France. He was born a noble, the son of Robert I, Duke of Normandy (ruled 1027-1035). Like many of the Normans, Robert and his son were descended from Vikings who had raided the region since the 8th century, also serving as mercenaries for local rulers.

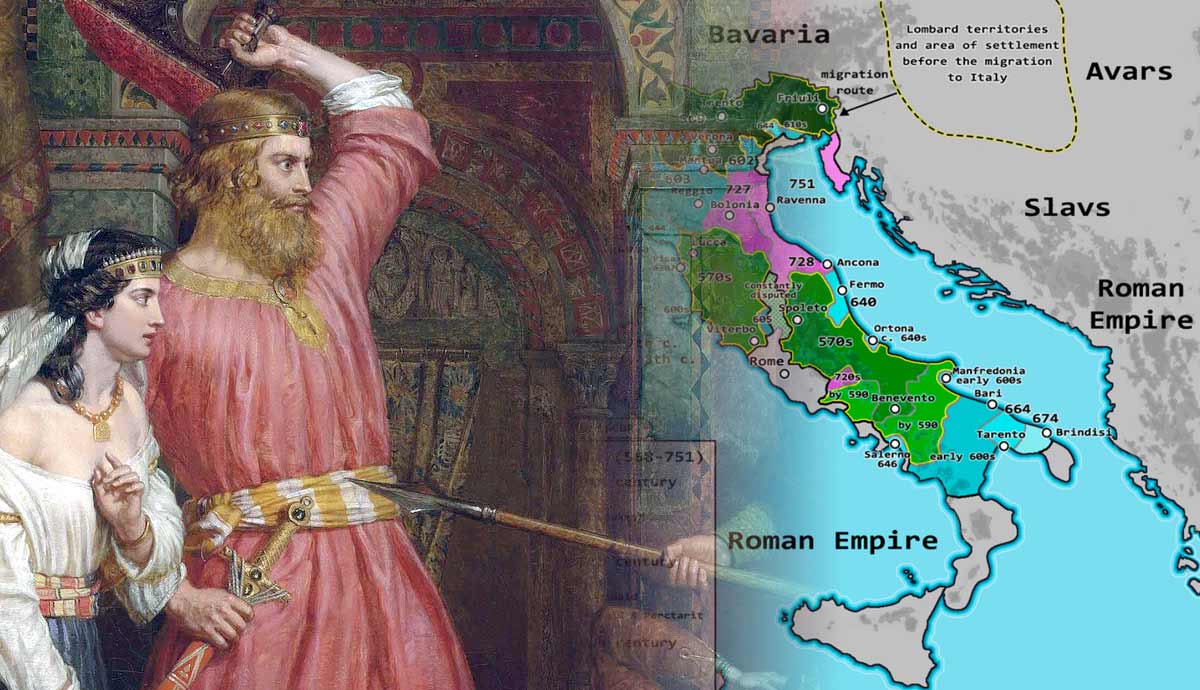

With their power and territory expanding, a Viking named Rollo established the Duchy of Normandy in 911. He had seized the region of Rouen in the late 9th century and then expanded into Bayeux. In 911, he helped the King of West Francia, Charles the Simple, defeat another Viking band. This led to a new alliance, which saw Rollo baptized and his territorial claims recognized as Normandy. He married Charles’s daughter, Gisela, to seal the deal.

William was a direct descendant of Rollo, six generations on, representing a surprisingly stable dynasty, with father succeeding son until William’s father, Robert, who succeeded his elder brother Richard III.

Nevertheless, there was some controversy surrounding William’s succession due to his mother, Herleva, who was not married to Robert. Consequently, William, who was born in 1028, was often known as William the Bastard in unfriendly sources. Some sources suggest that she was the daughter of a tanner or undertaker from the Norman town of Falaise, while others suggest she was of a more aristocratic background. Her aristocratic status is supported by the fact that she later married the Viscount of Conteville, and her brothers were reportedly influential during her son’s minority.

In 1035, his father died, and William inherited the throne of Normandy. Despite his status as a bastard and being just seven or eight years old, he was readily accepted as his father’s successor. Nevertheless, his lack of personal authority undermined ducal authority. Lesser nobles erected private castles, usurped important powers, and fought their own private wars. There were also attacks on William’s inner circle, with three of his guardians and his tutor dying violent deaths.

In 1042, when William was just 15 years old, he was knighted and finally considered the independent Duke of Normandy. He immediately set to work recovering the power that he had lost and brought the vassals of Normandy back under his control. He managed this with the assistance of his overlord, King Henry III of France, but during this time, William learned much and proved himself a strong warrior and ruler. He became known for simple and direct plans that ruthlessly exploited any opportunity. He also withdrew at the first sign of any disadvantage.

While Normandy was never fully secure, and William would fight rebellions and territory infringements for the rest of his life, after 1047 William was secure enough in Normandy that he could assist his king with battles in other areas, such as the king’s attempts to strengthen the France’s southern frontier and campaigns in the west against Geoffrey Martel, the Count of Anjou.

Political Alliances

During the early part of William’s reign, Edward the Confessor, a prince of England, was exiled to the continent by Viking usurpers. William established a good relationship with Edward during his exile, and he supported him when he was recalled to England as king in 1041. In the 1050s, during a difficult period in William’s reign, he conducted important negotiations with Edward, strengthening their alliance.

In 1049, William established an alliance with Count Baldwin V of Flanders, and in 1053, he married the count’s daughter, Matilda. This was despite the union being condemned by the Pope, showing William’s eagerness to seal the alliance with Baldwin.

In 1054, King Henry II and Geoffrey Martel formed an alliance against William, while he was also dealing with a new rebellion at home. William defeated the alliance at the Battle of Mortimer the same year. The issue was brought to a final conclusion when both Henry and Geoffrey died in 1060 and were replaced by weak rulers. This left Williams the most powerful leader in northern France.

In 1064, Edward sent Harold Godwinson, his brother-in-law, to William as an ambassador. The two men seemed to have formed an alliance and went on a campaign together into Brittany.

While all this was happening, William also implemented significant religious reforms. William made his half-brother Odo the Bishop of Bayeux, and worked with him and the other bishops to pass laws against simony (the selling of Church offices) and clerical marriages. He also endowed several monasteries and made several important monastic reforms with the support of Lanfranc of Pavia, a famous master of the liberal arts whom William welcomed into his territory.

William’s Disputed Claim to the English Crown

Eventually, William turned his attention to England. This was not a sudden and baseless attempt to conquer more land for himself. William asserted that he had a legitimate claim to the throne of England. Hence, his invasion in 1066 was merely a case of him taking by force what was rightfully his, at least as far as he was concerned.

William’s claim to the throne of England was partially based on his lineage. Edward the Confessor died childless in January 1066, and he was the son of King Aethelred the Unready and Emma of Normandy. This made William Edward’s first cousin once removed, giving him a familial claim to the English throne, even though he was not the closest claimant.

More important to William’s claim was his assertion that Edward had actually sworn to give the kingdom of England to William after his death. Some medieval sources claim that Edward had promised William the throne during the latter’s visit to England in 1051. Whether William actually visited England in that year or not, the promise is generally accepted as historical. Furthermore, in 1064, the powerful Harold Godwinson, Earl of Wessex, had sworn that William could succeed Edward while in Normandy.

Nevertheless, when Edward died, Harold immediately succeeded him. This was only logical, since he was from the most powerful family in Britain and had already done much of the ruling during the latter part of Edward’s reign. Furthermore, Harold claimed that Edward had specifically chosen him as his heir when he was on his deathbed.

Another claimant to the throne was Harald Hardrada, King of Norway, who had the support of Tostig, Harold Godwinson’s brother.

The Battle of Hastings in 1066

In 1066, when it became clear that Harold Godwinson had no intention of fulfilling Edward’s supposed promise, William decided to take England by force. According to William of Poitiers, a contemporary priest and chronicler, the Duke of Normandy’s planned invasion of England had the approval of Pope Alexander II.

A single organized invasion of England would not be easy, so William spent the summer making preparations. He used this time to construct an enormous fleet of ships. One contemporary source, William of Jumièges, claimed that he constructed 3,000 ships to use in the invasion. While this is widely understood as an exaggeration, it nonetheless testifies to the evident enormity of William’s preparation. He also assembled a large army from all over his own territory and various allied territories, including Flanders and Brittany.

An enormous and powerful army would be needed not only because of Harold’s strength, but also because Harold knew that William would likely try to invade.

Throughout the summer, Harold positioned his forces on the coast of England. However, at the summer’s end, he sent his troops home, thinking that William would not invade in the autumn. In reality, William would have invaded in August, but unfavourable winds made this unadvisable. Then, in September, he launched his ships.

William had a grand strategy and was also lucky. Harold had been forced to march north to deal with the invasion of Harald Hardrada, successfully defeating and killing him. Harold Godwinson then quickly marched south, by which time William had arrived. The Normans decided to hold position at Hastings, just next to the coast, rather than attempt to travel north to meet Harold.

Finally, on October 14, the two armies clashed. Though Harold had some initial successes, William was the superior tactician, employing fake retreats to draw out the enemy soldiers and then attack them with cavalry. By the end of the day, William had won the Battle of Hastings and Harold was dead. The Duke of Normandy was now William the Conqueror, King of England.

How William the Conqueror Came to Rule England

William of Normandy, despite being born out of wedlock, succeeded his father as Duke of Normandy. Initially being a fragile child leader, through alliances and military conquests, William established himself as the most powerful king in northern France.

When Edward the Confessor, the King of England, died in early 1066, William thought he had a good claim to the throne due to his family connection to Edward and promises reportedly made by Edward and his brother-in-law, Harold Godwinson. But when Harold went back on those promises and made himself king, William decided to take what he considered his by force. After months of preparation, William set sail for England with a huge army in September 1066 and won a decisive victory at the Battle of Hastings on October 14, 1066. He was now William the Conqueror, King of England and Normandy. The presence of the Normans in England would forever change the country.