Throughout its incredible history, there has seldom been a time in China when the Chinese rulers themselves have been overthrown at the hands of foreign invaders. That is what makes the Yuan Dynasty so interesting—and so culturally different from other famous dynasties in Chinese history such as the Song, Tang, Han, and Qing. The Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368) also saw huge developments in warfare, as well as the birth of some of medieval China’s most incredible figures. In this article, we will explore a brief history of the Yuan Dynasty China and the wonders that it had to offer.

The Origins of the Yuan Dynasty

The beginning of the Yuan Dynasty has been a point of contention for historians for centuries—did it start in 1271 or 1279? There are several reasons for both answers.

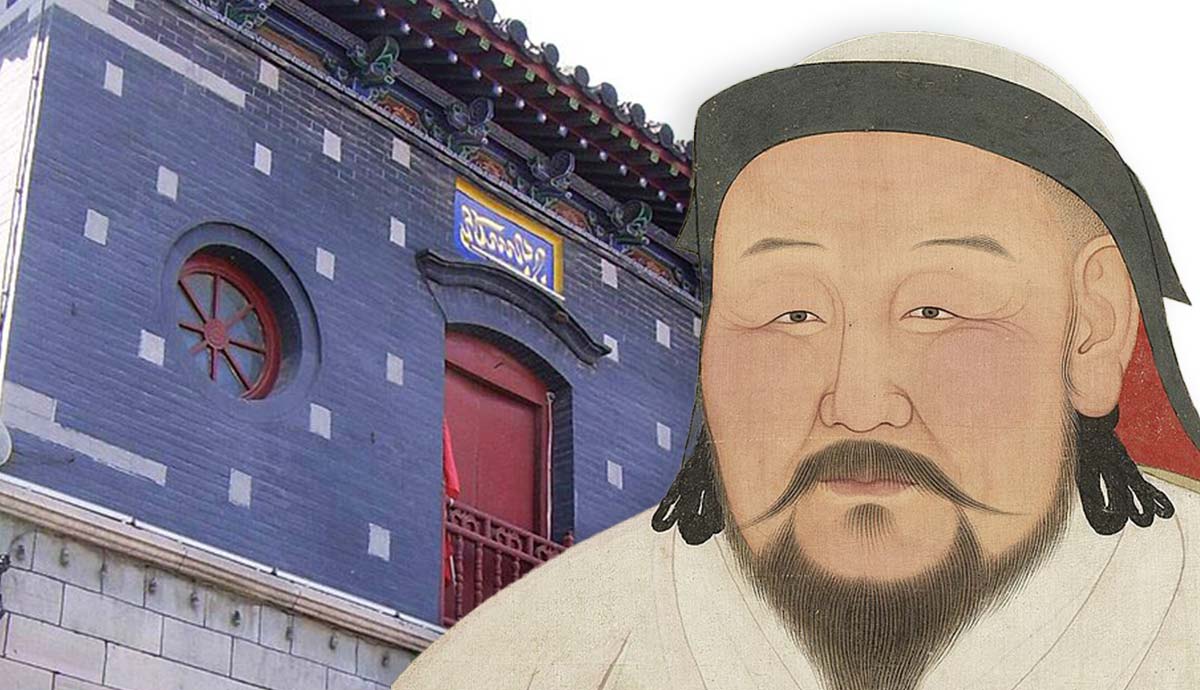

Prior to 1271, the Mongols had controlled areas of northern China for decades—particularly since the reign of Genghis Khan. It was Kublai Khan (a grandson of the great Genghis) who led the Mongols to conquer China and created the Yuan Dynasty (meaning Great Mongol State), announcing it in traditional Han style in 1271. This is why 1271 is often given as the official start date of the Yuan Dynasty: the Song Dynasty (which had ruled in China since 960 CE) had been formally overthrown by the Mongols, and the Yuan Dynasty was proclaimed.

So why should any other date be considered? Well, following Kublai Khan’s proclamation of the Yuan Dynasty and the “fall” of the Song Dynasty, the southern areas of China remained loyal to the Song Dynasty (some historians refer to this as the Southern Song Dynasty).

It would not be until March 19, 1279, at the Battle of Yamen that the outnumbered Yuan navy (they were allegedly outnumbered by ten to one) soundly defeated the last stand of the Song Dynasty, finally proclaiming official rule over all of China—hence why 1279 is also given as an official start date for the Yuan Dynasty.

Either way, by the turn of 1280, the Yuan Dynasty was well and truly in charge of China.

Kublai Khan: The Yuan Dynasty’s Greatest Ruler?

What is interesting to note about Kublai Khan’s rule is that his style of rule was an amalgamation of traditional Chinese rule, and Mongol ruling practices—he essentially had the best of both worlds.

In 1271, he formally proclaimed the Mandate of Heaven, which was a traditional way for ancient and imperial Chinese rulers to legitimize their rule: Kublai proclaimed himself the Son of Heaven, and thus ushered in a new era of Chinese history, promising it to be an age of peace and prosperity—much like the rulers of the Song, Tang, Han, and other earlier dynasties had done before him.

He used another Chinese method to establish his rule when he declared that 1272 was to be the “first year of the Great Yuan,” and made Khanbaliq the new capital (Khanbaliq is located where modern-day Beijing is).

This was another example of Khan using both Mongol and Chinese methods together to legitimize his rule for both Mongols and Chinese. He even evoked an image of a sage emperor by following the rules laid out by Confucius in ancient China, while simultaneously retaining his roots as a Mongol leader as a direct descendant of Genghis Khan.

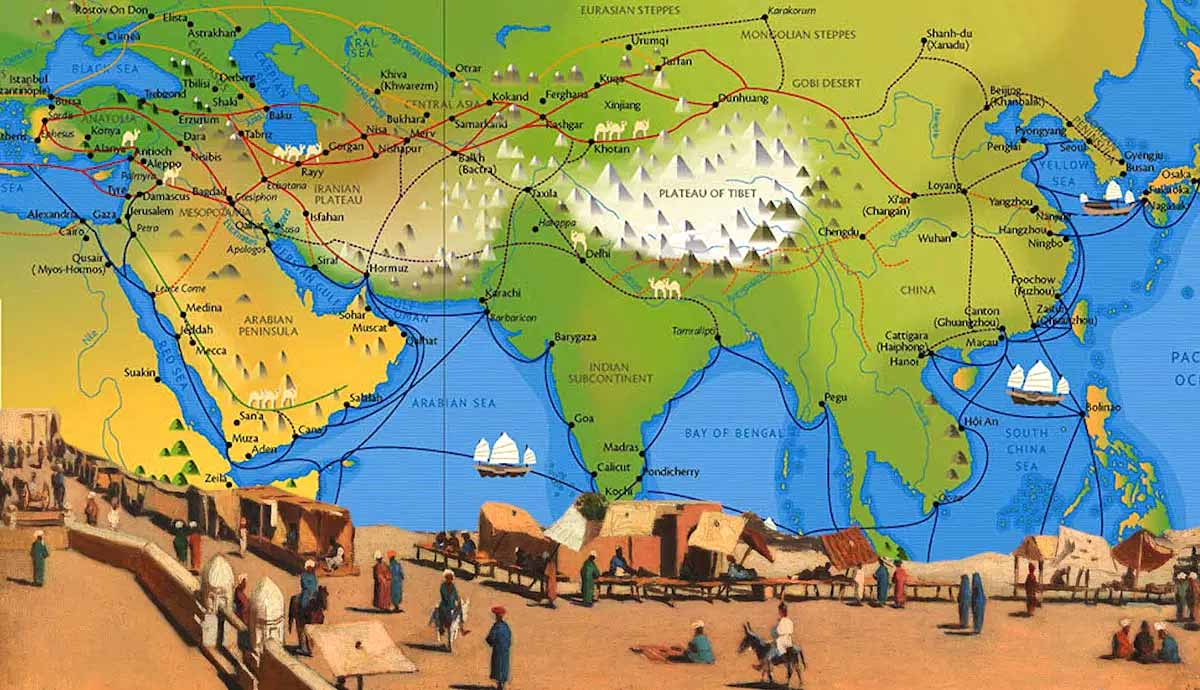

One of Khan’s most important diplomatic moves was his open support for trade through the Silk Roads—this helped the early Yuan economy to boom, and it was also aided by Kublai Khan’s continued use of the Mongol postal system, which he successfully integrated into Yuan Dynasty China. This was created through the use of skilled horse riders and postal stations, who could deliver messages at a speed unprecedented before, which aided with trade and communications across the vast empire.

It is the reign of Kublai Khan to which the term Pax Mongolica (Mongol peace) refers—a clear reference to the Pax Romana (Roman peace). It was during the rule of Kublai Khan and the early years of the Yuan Dynasty that peace and prosperity came to China in the Middle Ages.

Technological developments also took place during Kublai Khan’s reign, most notably the expansion of the Grand Canal, further connecting north and south China, and his encouragement of the use of jiaochao (paper bank notes).

However, perhaps the most notable aspect of Kublai Khan’s court and early Yuan rule was that he openly welcomed foreign visitors to China—most famously of all, the world-famous Venetian merchant Marco Polo. It is Marco Polo’s account of his stay in Kublai Khan’s court that created the best Western interpretation of contemporary Yuan China.

Yuan Society and Religion

While we could cover almost a full century of Mongol rule in China, the next section of this article will discuss Yuan society, and how it was structured.

Firstly, a new language was needed so that both Mongol and Chinese citizens could communicate with one another: this was essentially a mash-up of both languages and became known as the Phagspha script. While the majority of the Mongol emperors in the Yuan Dynasty could not master written Chinese, most of them took to Phagspha very well.

While most of the emperors had huge palaces commissioned, many of the Mongol rulers still stuck to what they knew best, and lived semi-nomadic lifestyles, frequently traveling around the realm.

The religion of the empire was another interesting factor in the running of the Yuan Dynasty. The establishment of the Yuan Dynasty saw a huge increase in the number of Muslims in China. However, Kublai Khan favored Tibetan Buddhism as a religion, and as a result, the official state religion of the Yuan Dynasty became Buddhism, and many Buddhist statues and sculptures in China date from the Yuan Period.

Social Class Structure in the Yuan Dynasty

As mentioned earlier, there was a distinct class structure under the Yuan Dynasty—and while it was generally deemed a period of peace and prosperity, a foreign nation invading and taking over a centuries-old dynasty meant that there was an element of racial structure to the class system in Yuan Dynasty China.

At the top of the chain were, of course, the Mongols. This comes as no surprise based on the fact that the class system was structured based on who the Mongols felt they could trust the most.

The group deemed as second-class citizens was named the Semu. This group was made up of non-Mongol Westerners, and those from Central Asia. This group included Muslims, Jews, Tibetans, and Christians.

The third group was simply called the Han. The term also encompassed Koreans and other ethnic groups who lived north of the Huaihe River, as well as the native north Chinese Han people.

The group that the Mongols deemed as the lowest under the Yuan Dynasty were the Nan, which meant “Southerners.” These were all the subjects of the short-lived Southern Song Dynasty, which the Yuan had overthrown in 1279 to formally establish the Yuan Dynasty.

Developments in Science and Technology in Yuan Dynasty China

One of the most unfair, yet commonly accepted, associations with Yuan Dynasty China is that there was a lull in scientific and technological advancements following the death of Kublai Khan in 1294.

This was not the case at all, and the perception of the Mongols as savages is simply outdated and xenophobic. It was during the Yuan Dynasty that the mathematician Zhu Shijie solved simultaneous equations with up to four coefficients, something that is equivalent to matrices today.

In fact, mathematical knowledge was actually brought to China by the Mongols, and, combined with Arab calendars, contributed to incredible mathematical developments in the years of the Yuan Dynasty.

Moreover, because of the melting pot of diverse cultures that was Yuan China, medicine evolved rapidly, too—Kublai Khan even created the Imperial Academy of Medicine to support the education of new physicians. Some of medieval China’s finest physicians lived during the Yuan Dynasty: the Mongol-born physician Hu Sihui mentioned the importance of a healthy diet in a medical treatise dated to 1330, while another physician, Wei Yilin, invented a suspension method for reducing dislocated joints, and he performed this with the use of anesthetics.

Paper money, as mentioned earlier, could not be produced without a printer—and the Mongols held a monopoly on printing in Yuan China, and are often credited with bringing printing into the mainstream in China. For example, in 1273 the Mongols created the Imperial Library Directorate, which was a government-sponsored printing office. By 1328, annual sales of printed calendars had reached over three million in the Yuan Dynasty alone, which goes to show the sheer volume of printing that was happening during this period.

The Decline of the Yuan Dynasty

While the early years of the Yuan Dynasty under the rule of Kublai Khan had seen great peace and prosperity come to medieval China, the later years would take a different tack.

The 1320s saw corrupt emperors and regicide, and popular rebellions—which had been rare during the early years of the Yuan Dynasty—cropped up more often. Pretenders to the Imperial Throne and relatives of descendants of Genghis Khan battled it out, often at the expense of peasants who suffered at their hands, either in their armies or their crop yield.

The 1340s saw a range of natural disasters including floods, drought, and resulting famines, which finally culminated in a series of rebellions against the Yuan government known as the Red Turban Rebellion.

The Red Turban Rebellion had started in 1351, and by 1354 had gained so much popular support that the emperor ordered it to be put down, but failed.

It was thanks to the leadership of the Red Turban Rebellion, under Zhu Yuanzhang, that the emperor was forced to flee north to Shangdu from his base in Khanbaliq in 1368, at the arrival of the Ming Dynasty. It was Zhu Yuanzhang who would go on to be crowned as the Hongwu Emperor, the first Emperor of the Ming Dynasty, who would rule China from 1368 until 1644.

The Yuan Dynasty: In Conclusion

While the Yuan Dynasty came to an abrupt end in 1368 after less than a century of rule, at the hands of the mighty Ming Dynasty (which in turn would go on to rule for almost 300 years) its achievements cannot be overlooked.

The perception of the Yuan Dynasty as a mixed amalgamation of tribes and savages is simply wrong—some of medieval China’s greatest minds were born during the Yuan Dynasty and helped shape it through their knowledge and expertise in a range of fields such as engineering, mathematics, and science.

While Kublai Khan’s leadership saw an age of peace and prosperity brought to China, it was not the royalty who suffered but the conquered classes—with the Mongols favoring their own over the Han Chinese.

Finally, the Yuan Dynasty should not be remembered as the Mongols simply occupying China—the Mongols made an effort to assimilate into Chinese culture, which is why Yuan Dynasty China is one of the most important eras of Chinese history, with its effect still being felt today.