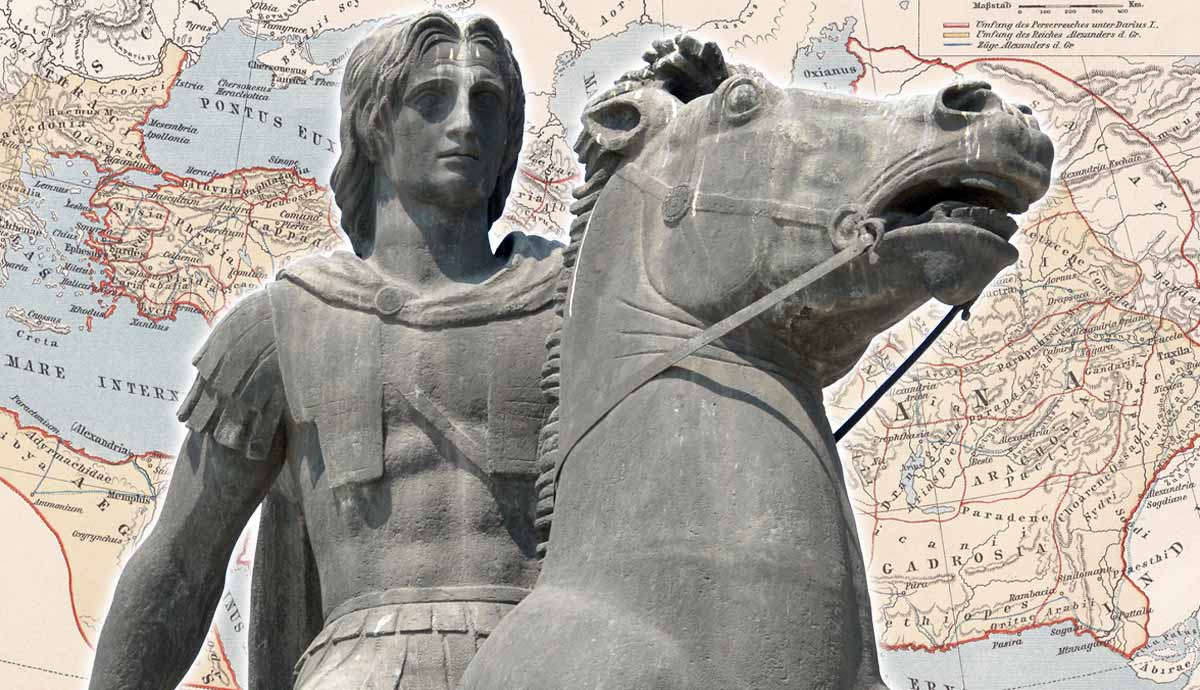

Alexander III of Macedon was born in 356 BCE, the son of King Philip II. By his death in 323 BCE, at the age of just 33, he would be Alexander the Great, King of Macedon, Hegemon of the Hellenic League, Pharaoh of Egypt, Great King of Persia, and the ruler of an empire that stretched from Greece and Egypt in the west to India in the east. Few names in history are as famous, so much so that it can be difficult to separate history and myth. Read on to discover the life and legacy of Alexander the Great.

Timeline & Key Battles

| July 356 BCE | Alexander is born in Pella, Macedon, son of King Philip II of Macedon of the Argead dynasty and Olympias, eldest daughter of King Neoptolemus I of Epirus. |

| 338 BCE | Battle of Chaeronea – The 18-year-old Alexander led his father’s Macedonian cavalry against the forces of Thebes, Athens, and other Greek allies. The battle was a crushing victory for Philip and the Macedonians. |

| 336 BCE | Assassination of Philip II and accession of Alexander. |

| 335 BCE | Battle of Thebes – One of Alexander’s first acts as king was the bloody suppression of an attempted revolt against Macedonian hegemony in Greece by Thebes. |

| May 334 BCE | Battle of the Granicus – Alexander crosses the Hellespont into Asia and wins his first battle against the Persian Empire. |

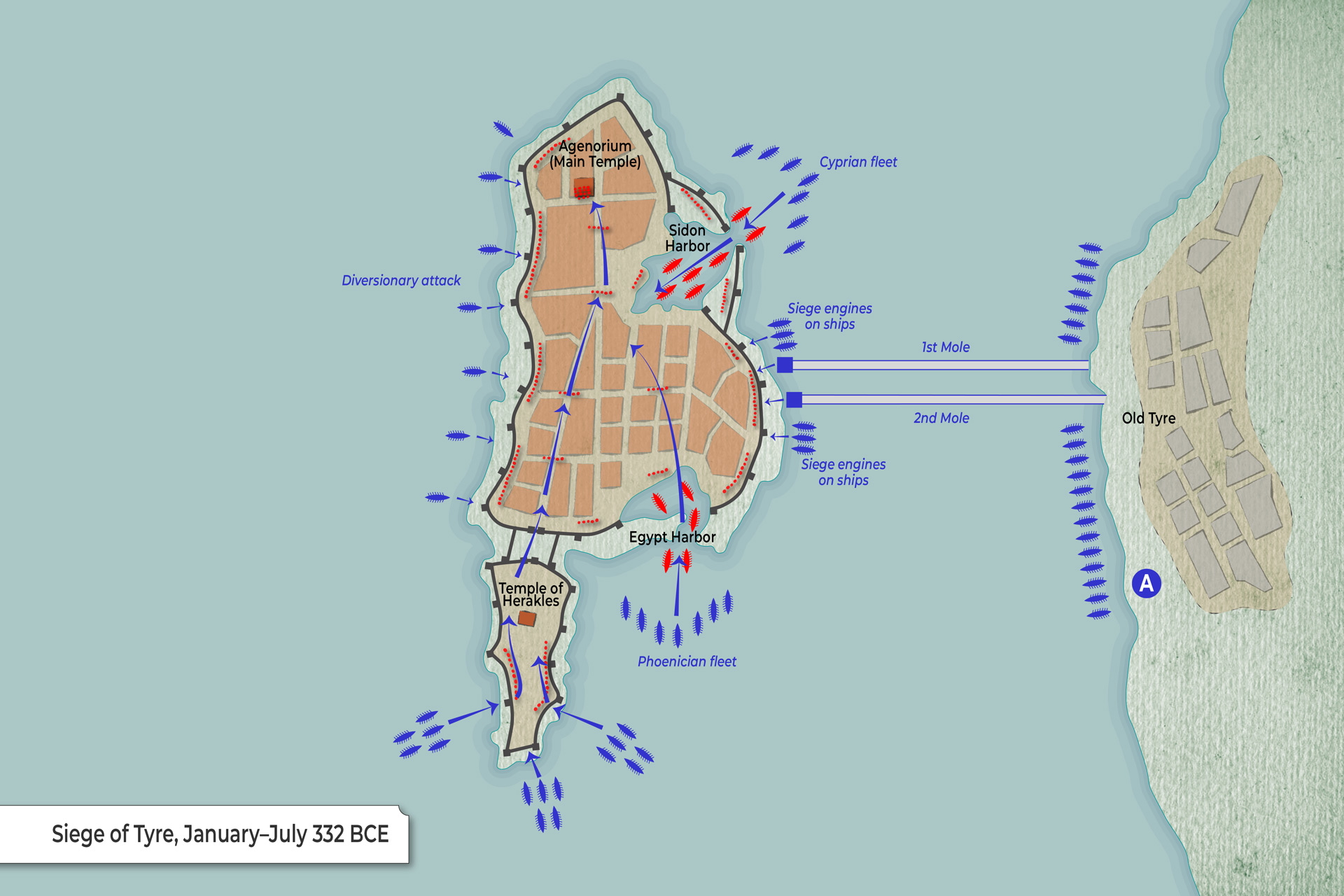

| 332 BCE | Siege of Tyre – Alexander’s forces build a mole to capture the key strategic city on the Phoenician coast. |

| 332 BCE | Alexander takes Egypt and visits the Oracle of Ammon at Siwa to confirm his divine parentage. |

| November 333 BCE | Battle of Issus – The next large battle against the Persians saw Alexander confront Darius III for the first time. |

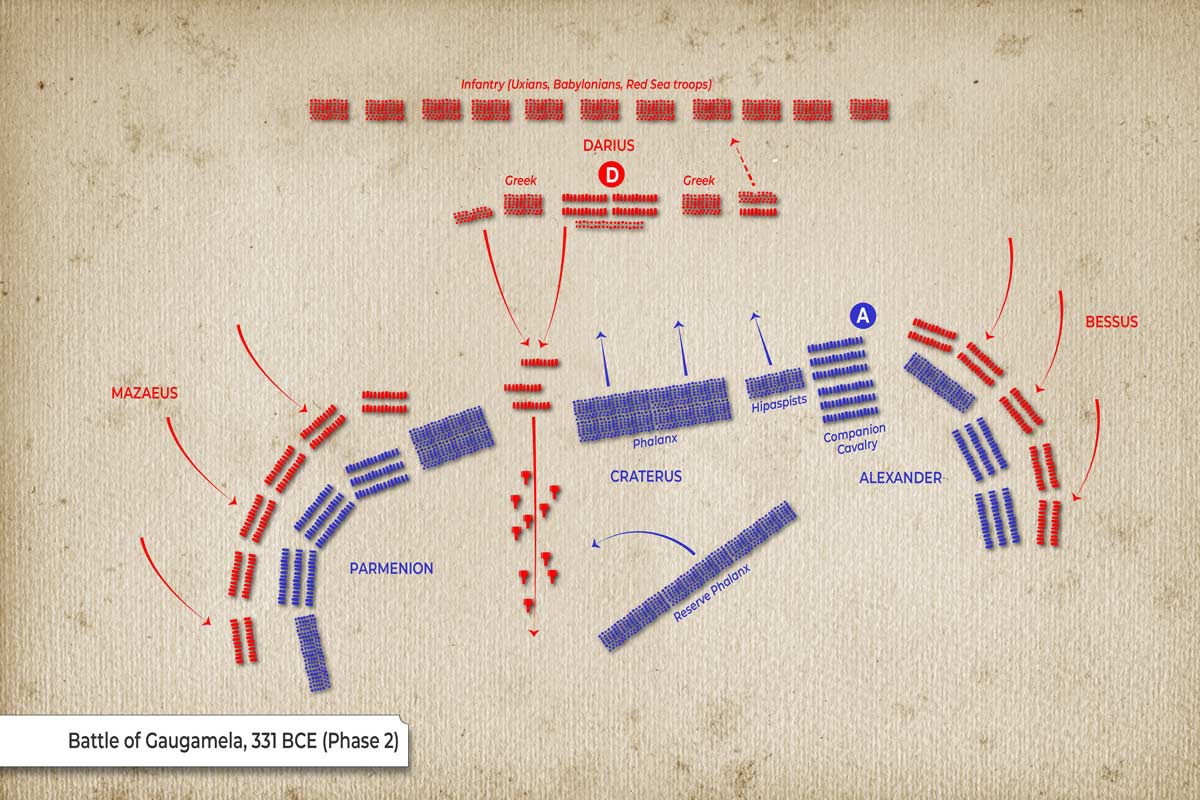

| October 331 BCE | Battle of Gaugamela – Alexander’s final crushing defeat of Darius III, after which he captures Babylon, Susa, and Persepolis. |

| 330-328 BCE | Alexander continues his conquest of Asia with campaigns in Bactria and Sogdiana. |

| 327 BCE | Siege of the Sogdian Rock – The defenders taunt Alexander that he would need “men with wings” to capture the seemingly impregnable mountaintop fortress. Alexander marries the Bactrian princess Roxanna, later the mother of his son Alexander IV (born 323 BCE). |

| May 326 BCE | Battle of the Hydaspes (Jhelum) – Alexander leads his men into India, culminating in his final great battle, this time against the Indian King, Porus, in the Punjab. |

| 326-325 BCE | The Macedonian army revolts, and Alexander leads them back to Persia through the Gedrosian Desert. |

| 324 BCE |

|

| June 323 BCE | Alexander dies in Babylon, just shy of 33 years old. |

Early Life

Alexander was born in July 356 BCE, in the city of Pella, the capital of the ancient kingdom of Macedon. According to a rumor recorded by the 2nd-century CE biographer Plutarch, on the day of Alexander’s birth, the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus burnt down, as the gods were distracted by the birth of the future Great.

Before he could be great, Alexander had to survive the dangerous Macedonian court. His father, King Philip II, had a handful of wives, as was commonplace to ensure multiple heirs. Alexander’s mother, Olympias, was the daughter of King Neoptolemus I, the ruler of the neighboring kingdom of Epirus. For a while, the colorful Olympias appears to have been Philip’s favorite wife. After the Battle of Chaeronea in 338 BCE, he set up gold and ivory statues of himself, Alexander, and Olympias at the Panhellenic sanctuary at Olympia. Olympias alone among Philip’s wives enjoyed such an opulent and public demonstration of his affections.

Alexander’s birth became the subject of a number of rumors and legends, most invented after his rise to power. Many were meant to be portents of his future greatness and hint at a divine lineage. According to one, recorded by Plutarch, on the night of her union with Philip, Olympias dreamt that her womb was struck by a thunderbolt. The implication was that her offspring was sired by Zeus.

As a young man, Alexander already displayed unusual boldness and charisma. One famous anecdote relates to his taming of the horse Bucephalus. Brought to the Macedonian court by a Thessalian merchant, no one could tame the beast, but Alexander bet his father that he could. He had noticed that the horse was scared of its own shadow, so he simply turned it to face the sun. Philip, delighted in the boldness and success of his son, apparently declared, “You must find a kingdom big enough for your ambitions. Macedon is too small for you!”

Education

As Philip’s son, Alexander had to be prepared to rule and had to learn to navigate an increasingly tumultuous world. Philip, through skilled leadership and military reforms, had catapulted his kingdom to the forefront of Greek politics, much to the chagrin of legacy powers, notably Athens, Sparta, and Thebes. To justify his position, Philip began to present himself as a champion of Greece and the most suitable man to lead a punitive expedition against the Persian empire. Nevertheless, his policies attracted ire and subterfuge in Greece, especially from the Athenian rhetor Demosthenes, who took a staunch anti-Macedonian stance.

Preparing his son for rule, Philip charged several tutors with his education. In early childhood, it was Leonidas, a relative of Olympias. Recalling his famous namesake, Leonidas was Spartan in his outlook. He insisted that Alexander forgo the luxuries of his royal station, which might corrupt his sensibilities. He once famously chastized Alexander for throwing large quantities of incense onto a sacrificial fire. He urged the young man to be more sparing of so precious a resource until he had conquered the country where it grew. Years later, when Alexander was lord of Asia, he sent his old tutor a staggering 600 talents of incense with an accompanying message that he could now be less stingy in his offerings to the gods.

Alexander met his most famous tutor when he was a teenager: Aristotle, the renowned student of Plato. Having recently destroyed Aristotle’s hometown of Stageira, Philip offered its reconstruction in exchange for his son’s education. Aristotle agreed, and Alexander was taught by the philosopher at the Temple of the Nymphs at Mieza. The young prince was not Aristotle’s sole pupil. As was the custom, he was joined by some of his future comrades, including Ptolemy, Hephaestion, and Cassander. They studied topics such as philosophy, logic, medicine, morality, art, and religion.

It was also under the philosopher’s tutelage that Alexander developed his great love of the Homeric epics and probably his desire to rival the greatness of Achilles. Later, while on campaign, Alexander carried with him a copy of the Iliad annotated by his former tutor.

King of Macedon

Alexander’s affinity for Achilles reflects his warrior destiny. He displayed military talent from a young age, which was the main reason he was preferred over his older brother, Philip III Arrhidaeus. At just 16, acting as regent, Alexander quashed an uprising of the Maedi tribe, a group of Thracians who had used Philip’s absence on campaign to revolt. Later, in 338 BCE, the young prince played a decisive role in the Macedonian victory at Chaeronae, breaking the Theban lines and paving the way for the rout that followed.

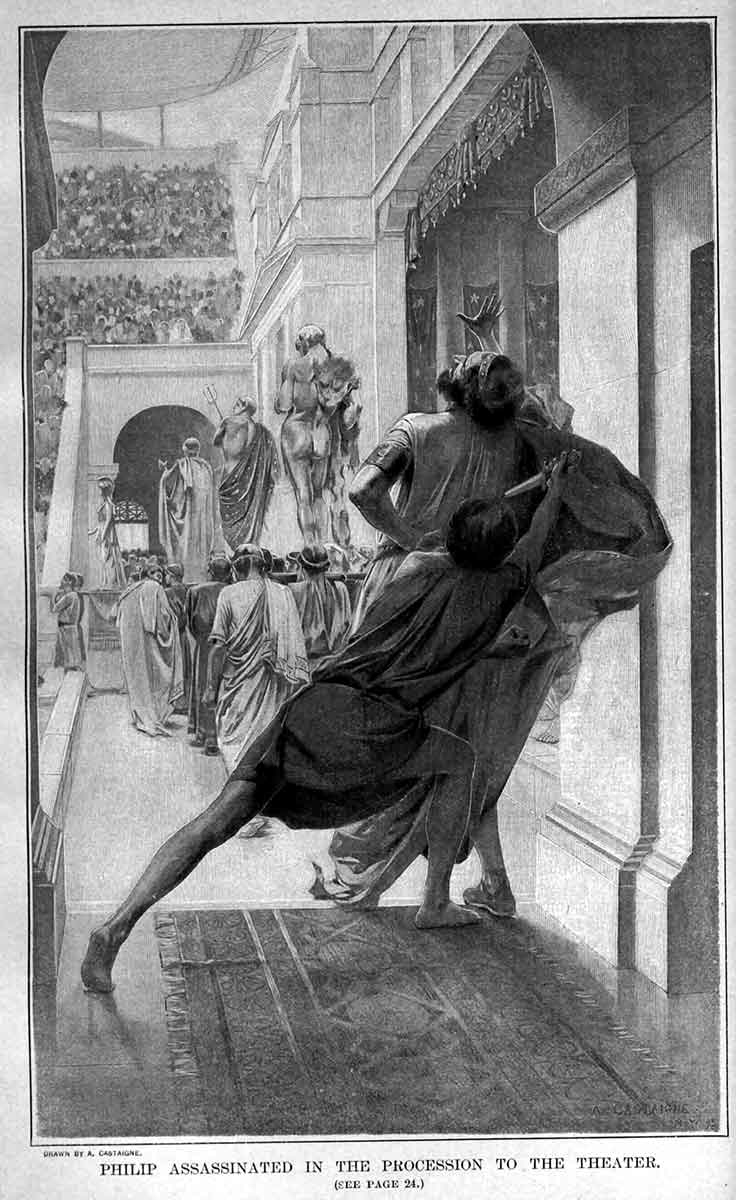

Philip’s marriage to Cleopatra Eurydice, a Macedonian noblewoman, in 337 BCE briefly jeopardized Alexander’s future as the heir apparent. But Philip’s assassination the following year at the hands of one of his bodyguards, Pausanius of Orestis, resolved the issue. Acting decisively, Alexander was recognized as king by the assembled Macedonian nobles and soldiers. He then quickly consolidated his power, executing the Lyncestian Princes accused of collusion in Philip’s assassination and other rivals. Some ancient authors suggest that Olympias and the 20-year-old Alexander were complicit in the assassination since they benefited most, but there is no firm evidence to support these claims. With his position secured and his mother acting as regent, Alexander left Macedon and picked up Philip’s plans for the great panhellenic campaign against the Persian Empire.

Conquest of the Persian Empire

Before he could start his campaign, Alexander had to deal with trouble in Greece. In 335 BCE, the Athenians and Thebans, battered but undeterred by their chastening defeat at Chaeronae, used the death of Philip to attempt to throw off Macedonian influence. Alexander, campaigning against the neighboring Thracians, quickly marched south and drew up his army outside Thebes. The city was razed by the Macedonians and the majority of its population killed or enslaved. Athens was suitably cowed. The brutal response allowed Alexander to move his forces across the Hellespont and into Asia, confident of no further trouble in Greece.

Alexander crossed the Hellespont in 334 BCE and began to march south through Asia Minor. Historians estimate that he had an army of over 50,000 infantry and cavalry. It was not long before, in May 334 BCE, his army met the Persian forces for the first time at the Granicus River (the modern Biga River, Turkey). The Persians were led by a group of satraps, including Arsites, satrap of Phrygia, and the Greek mercenary leader Memnon of Rhodes.

Memnon allegedly advised the Persians to avoid open battle and suggested a scorched earth policy to starve Alexander out of Asia, but the Persians chose battle. The Macedonians won a decisive victory and continued their advance deeper into Persian territory, heading south down the Ionian coast.

Alexander captured the city of Halicarnassus in his first successful siege. From there, the Macedonians advanced into Lycia and Pamphylia. It was there, in the city of Gordium, that Alexander cut through the Gordian Knot, a hitherto unresolvable puzzle. An act of propaganda, it was said that whoever succeeded would be “King of Asia.”

The Macedonian march continued into Syria, where they encountered the great Persian King Darius III and his army. Clashing at the Battle of Issus in November 333 BCE, the Macedonians were vastly outnumbered, at least two to one. Nevertheless, Alexander based his strategy on the topography of the battleground and achieved a crushing victory. Darius fled and, despite a desperate pursuit, evaded the Macedonians.

After Issus, the Macedonians continued their advance south along the coast of the Levant. In 332 BCE, they besieged the city of Tyre with its formidable coastal fortifications. It was a gruelling ordeal, and when the Macedonians eventually breached the walls, the slaughter inside the city was terrible.

After Tyre, the Macedonians entered Egypt and “liberated” the ancient land from Persian rule. Control of the region gave Alexander not only mastery of the eastern Mediterranean but also access to precious resources: This was crucial for the future of the campaign. After all, an army marches on its stomach. From Egypt, the Macedonians marched east once more, into Assyria, as they chased down Darius. The decisive battle against the beleaguered Persian King came in October 331 BCE at Gaugamela.

Once again, the heavily outnumbered Macedonian forces were victorious. Darius fled and had plans to retreat east and raise another army, but confidence in his leadership was brittle after two devastating defeats. He was murdered by his men.

Victory at Gaugamela confirmed Alexander as the lord of Asia, which he celebrated with a triumphal entry into the great city of Babylon. Despite what some of his men may have thought, this was not the end of the Macedonian war in Asia. To legitimize his position, Alexander decided to pursue Darius’ killers.

King of Asia

Alexander’s campaign continued, heading first to fabulously wealthy Susa and then majestic Persepolis, the ceremonial capital of the Persian Empire. In a controversial episode, the great city of Persepolis was burnt. Whether this was arson in retaliation for Xerxes’ destruction of the Athenian Acropolis in 480 BCE, a drunken accident, or simply wanton destruction remains debatable. In pursuit of the killers of Darius, Alexander and his armies marched across much of modern Afghanistan. In 329 BCE, the principal conspirator, Bessus, was betrayed and executed. But still, there was no end to the fighting.

The Sogdians, from modern Uzbekistan, rebelled against Macedonian incursions into their territory. They were defeated at the Battle of Jaxartes in 327 BCE. The Macedonians then laid siege to the great Sogdian fortress of Ariamazes. So high was the fortress that the overconfident defenders said that the Macedonians would need wings to take the fortress. Several hundred brave Macedonians scaled the sheer cliffs. Alexander informed the besieged to look up at Macedon’s “Winged Men,” resulting in their surrender. Inside the fortress, Alexander met the princess Roxana, whom he took as his wife, cementing a political relationship with the region.

March Into India

With resistance to Macedonian power in the Persian Empire quashed, Alexander turned his men toward the Indian subcontinent. This was to be the final stage of his massive campaign of conquest. Inviting some chieftains of Ghandhara to submit to him, not all accepted the king’s invitation. His main adversary after crossing into India was Porus, a king who ruled over territory between the Jhelum and Chenab Rivers (now in Punjab, Pakistan). The two kings met in the final great battle of Alexander’s life, the Battle of the Hydaspes, in May 326 BCE.

Although the Macedonians were victorious, the battle was costly. Morale, already low among the Macedonians who had marched from Pella to the Punjab, dropped further. They were shaken by heavy losses and the terror of confronting Porus’ formidable war elephants. For Alexander, there was also the great personal loss of his horse Bucephalus in the battle. The horse was honored by a newly founded city, Boukephala, built on the site of the battle.

The Macedonian army reached its limit, and on the banks of the Hyphasis River, they revolted. Alexander’s campaigns of conquest were brought to an end. The final stage of their journey was to follow the Indus River east. Arriving at the coast, his forces were divided into two. The lucky ones sailed the Persian Gulf with Admiral Nearchus. The others, led by Alexander, marched back to Persia through the desolate wastes of the Gedrosian Desert. Huge numbers of Alexander’s men perished en route, but they arrived in the Persian city of Susa in 324 BCE.

As Governor & Administrator

By the time of his return to Susa in 324 BCE, Alexander had conquered a territory that stretched from the Macedonian capital of Pella in Europe across to the Indus in Asia. Covering more than five million square kilometers, no single individual in the ancient world had ever ruled such a large kingdom. The challenge for the young king was how to govern this extraordinarily vast and incredibly diverse dominion. The short answer was that, fundamentally, the Macedonian king kept the existing power structures largely in place.

His campaigns of conquest were not followed by wholesale changes to local societies. In Persia, the system of satrapies that had been used by Darius to control his territories remained in place. The only real change was that many Persian satraps were replaced by Macedonian nobles, and taxes collected were delivered to a different king.

The lack of fundamental change allowed Alexander to continue his advance without getting bogged down in messy administrative issues. But this approach did not provide a solid basis for lasting power. Moreover, much of Alexander’s success in holding his empire together was down to his personal charisma and ability to coerce and convince his men to follow his instructions. The further east, the less stable Alexander’s rule. His reign was plagued by stories of maladministration, corruption, and sedition.

Hellenization

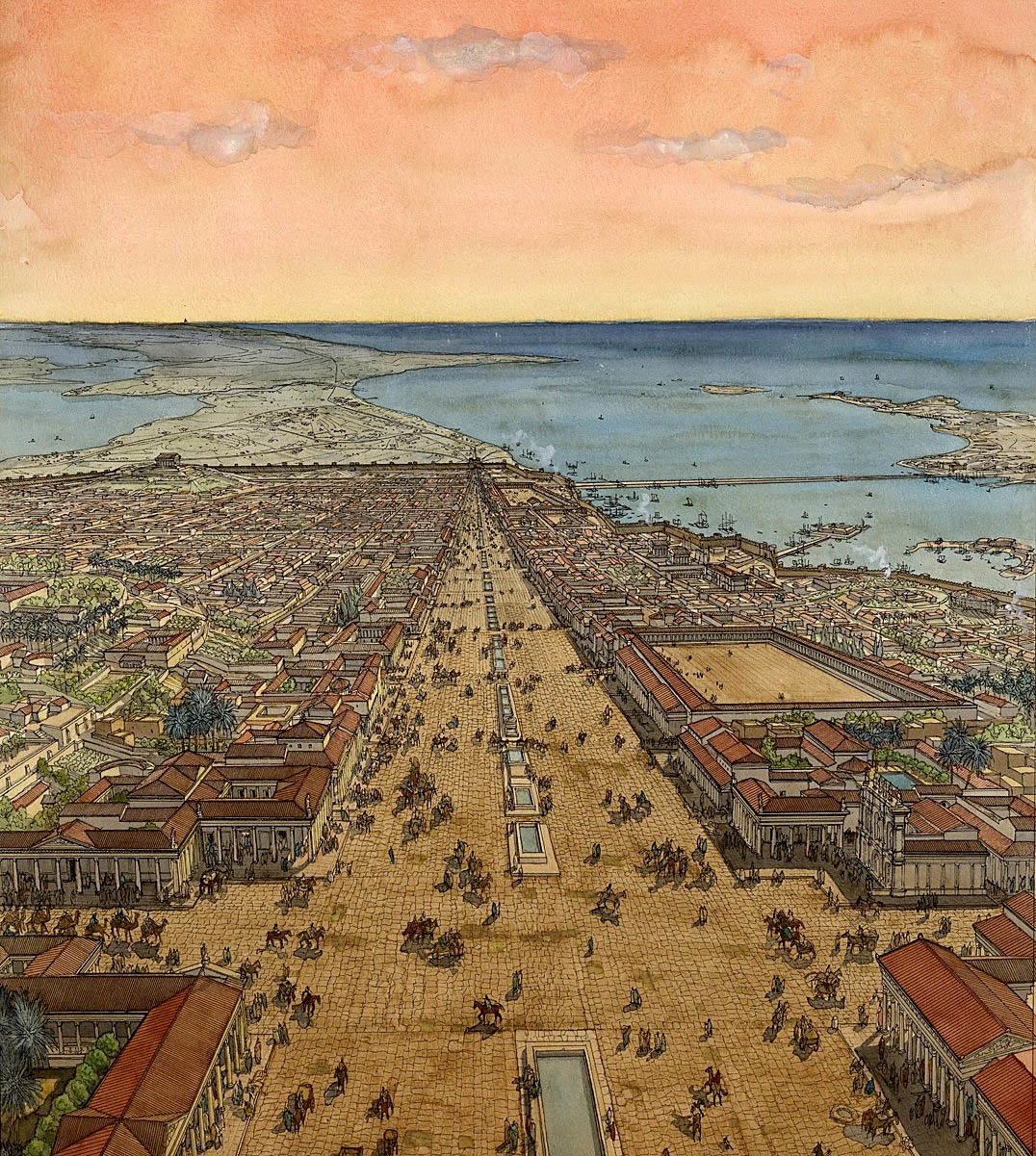

While Alexander’s empire may have left administrative structures largely in place, it had a profound cultural impact on the conquered territories. One of the most impactful consequences of Alexander’s conquests was the foundation of Greek cities across the region. Most were found east of the Tigris, suggesting that they were designed to serve a defensive role. But a significant number of them bore the king’s name, suggesting their purpose was also ideological.

The most famous of the many Alexandrias founded by the king was the first. Alexandria, established on the Mediterranean coast of Egypt in 331 BCE, quickly became one of the most important cities in the ancient Mediterranean world. Famous for its great lighthouse and grand library, it became a center of learning and culture in the ancient world for centuries.

Beyond the confines of his cities, Alexander’s conquests were responsible for a process known to historians as “Hellenization,” the spread of recognizably Greek culture. Greek language, religion, architecture, and aesthetic ideals spread throughout the territory conquered by Alexander. Greek aesthetics can be seen in the art of Gandhara and Ionic columns in the temples of Pakistan.

Alexander’s Hubris

Cultural exchange was not one-sided. The Macedonian court also absorbed ideas from conquered territories, in particular the Persian custom of proskynesis. This was ceremonial prostration on the ground before the king, typical in the Persian court, but considered offensive in Macedonian culture. Nevertheless, Alexander started to receive proskynesis, attracting scorn from the Macedonians, who thought it alienated the king from his court. This, combined with increased integration of the Persian elite into the empire’s political and administrative hierarchies, meant that tensions at court were high.

Another source of contention was the question of Alexander’s divinity. While in Egypt, Alexander had marched through the desert to visit the Oracle at Siwa, an oasis in the Libyan desert. There, the sources report that the Macedonian king was informed of his divine parentage: he was the son of Amun. This led, in time, to his acknowledging Zeus-Ammon as his father, represented on his coin iconography by appearing with ram horns. Alexander’s desire for divinity, something largely antithetical to the Greek mindset, furthered the divide between Alexander and the Macedonians.

A manifestation of this tension occurred when, back in Persia, Alexander decided to reassign Cleitus the Black, an older general who had served under Philip. Unhappy at the reassignment and with changes in Alexander’s behavior, Cleitus stated publicly that Alexander’s achievements depended on those of Philip, and that he was the son of a god and not the previous king, then he was not the legitimate Macedonian king. In a fit of anger, Alexander killed him with a pike to the chest.

Decline & Downfall

This is just one example of the unhappiness that plagued Alexander on his return to Persia. His ambition for further conquest was thwarted by his men, many of whom perished on the gruelling march across the Gedrosian desert. He also discovered that his empire was suffering the effects of maladministration and corruption. Executions followed, and another mutiny when Alexander attempted to discharge a number of his veterans.

While the Macedonians criticized Alexander for his adoption of Persian customs and integration of Persian soldiers into the Macedonian army and high command, he continued to court Persian culture. As well as impregnating Roxana with a son who would be born after his death, he married Stateira, the daughter of Darius III, and Parysatis II, the daughter of Artaxerxes III, another former Persian king. He also had many of his Macedonian officers marry Persian women in what are known as the Susa weddings to promote integration.

Alexander was stricken by personal tragedy in the autumn of 324 BCE, when his close friend and possible lover Hephaestion fell ill and died. He entered into a period of extreme mourning, akin to the grief displayed by Achilles at the death of Patroclus. He allegedly ordered the temple of Asclepius, the healing god, in Ecbatana destroyed in revenge for the death of his companion.

Death of a God-King

The challenge of his new position as king of a vast empire weighed heavily on Alexander and he may have turned to excessive alcohol consumption. His body, weakened by years of campaigning and serious injuries, eventually gave up. On June 11, 323 BCE, Alexander died in the Palace of Nebuchadnezzar II in Babylon. He was 33 years old. For just over a week, he had been increasingly debilitated by a fever, until it eventually overcame him. Theories soon circulated that Alexander had been poisoned. There is no evidence to support this claim, and the rumor probably arose because people simply could not believe he died of natural causes.

Grief quickly descended into fear and chaos. Alexander’s vast domains were just that: Alexander’s. How would the Macedonians retain them without Alexander at their head? When they gathered around the king to ask who exactly he wished to be his successor, the enfeebled warlord was only able to muster a cryptic response: his empire should go “to the strongest.” The seeds were sown for decades of horrific bloodshed as Alexander’s successors, known as the Diadochi, fought ruthlessly among themselves for portions of the empire.

Alexander’s Tomb

As the battle of Alexander’s dominion began, his earthly remains became a considerable prize. Originally, his body was dispatched from Babylon in a gold sarcophagus back to Macedon, where he would presumably be buried with other members of the Argead dynasty at Vergina. But this apparently contradicted Alexander’s own wishes, to be interred as Siwa close to his father Zeus-Ammon.

But Alexander’s body never made it back to Macedon. His sarcophagus was seized by Ptolemy, one of Alexander’s closest companions, who successfully carved out a dominion for himself in Egypt, establishing the Ptolemaic dynasty. It was the most stable of the emergent Hellenistic kingdoms, surviving until it was conquered by Rome in 31 BCE. But Ptolemy did not take sole possession of Alexander’s relics. Other generals, including Perdiccas and Eumenes, took possession of other symbolically significant icons of Alexander’s authority, including his armor, diadem, and royal scepter.

Ptolemy initially placed Alexander’s body in a temporary tomb near his Memphis base. But as the city of Alexandria grew and became the new capital, his body was transferred there, where it was housed in a great mausoleum and temple called the Soma.

Augustus at the Tomb of Alexander the Great, by Lionel Noel Royer, 1878, private collection

The body of Alexander attracted a constant stream of high-profile visitors over the centuries, including high-ranking Romans like Julius Caesar, Pompey Magnus, and Augustus. The figure of Alexander loomed large in the Roman imperial mindset; ambitions of conquest in the east saw various emperors present themselves as the imitators of Alexander. Such delusions of grandeur were not merely limited to vilified emperors such as Caracalla; even Trajan, the optimus princeps, viewed Alexander as a source of inspiration as he campaigned against the Parthians. Nevertheless, after a visit by Septimius Severus at the turn of the 3rd century CE, the tomb was closed.

After this date, the location of the tomb and Alexander’s remains become one of ancient history’s great mysteries. The closure of all pagan temples following the Theodosian Decrees of 381 CE saw Alexander’s mausoleum disappear from the map of Alexandria. There are theories that Alexander’s body was moved to other parts of Egypt, back to Macedon, or even to Venice. The hunt for his remains is ongoing.

Modern Interpretations

Even before his demise, Alexander’s life had become legendary, and he became more myth than man over the centuries. This means that while we have a huge array of sources for the life and character of Alexander the Great, differentiating between fact and fiction is often challenging. Very real acts of

improbable courage and victory – such as the ‘winged men’ of Macedon who triumphed in the Sogdian mountains – stretch the imagination. Some of the most incredible stories about Alexander are preserved in the Alexander Romance, by pseudo-Callisthenes, which was a collection of tall tales gathered in Alexandria. The stories in the Romance include the suggestion that Alexander became the lover of Thalestris, the Queen of the Amazons.

But there is no denying Alexander’s incredible impact. His conquering army spread Greek culture to much of the Middle East. Alexander himself inspired other ambitious generals, like Julius Caesar, who, at the age of 33, allegedly lamented that he had not yet been able to match the Macedonian king’s exploits. Alexander was certainly treated as a hero in Greek and Roman stories of his life.

But many modern scholars take a less romantic view of Alexander and his legacy. He was clearly a master tactician and a charismatic leader of men, but he was also a warlord who marched his soldiers tens of thousands of miles on a mission of bloody conquest, slaughtering not only other soldiers but also women and children caught in the crossfire. This has led to some negative testimonies about his life throughout history. For example, in Persian Zoroastrian literature, he is called the “accursed” (gujastak). Modern scholars are also increasingly turning away from the romanticized Greco-Roman view of Alexander to see him through the eyes of the conquered.

Alexander’s Legacy

In his Biography of Alexander the Great, which he pairs with Julius Caesar in his Parallel Lives, Plutarch pleads for forgiveness with his readers, highlighting that it would be impossible to recount all the deeds of Alexander, so great were they.

It was said that Alexander was driven by pothos . This was a burning desire to explore new horizons and conquer new territories. In his short life, the charismatic Macedonian king led his army from Pella to the Pubjab. Vast territories were won by the Macedonians at the lethal point of a sarissa, as their king marched ever on for glory, and perhaps even divinity, leaving a bloody trail in his wake. While Alexander’s empire was great, it was also ephemeral. Without his magnetism to hold it together, it soon fractured.

While the empire was short-lived, the legacy of Alexander the Great was far from fleeting. The stories of his life and conquests continues to fascinate, two millennia on.