Without a doubt, the roots of western civilization were sown within the Hellenic world. Especially through architecture, the heritage of the ancient Greeks is vast and diverse. Therefore, a closer look at their still-existing architectural wonders is a rich and rewarding experience.

We can define as ancient Greek any construction built between 600 BCE up until the 1st century CE, within the Greek mainland, the Peloponnese, the Aegean Islands, and in colonies in Anatolia and Italy. The main types of ancient Greek architectural works are temples, mausoleums, gateways, public monuments, council buildings, and theaters.

1. A Unique Wonder Among Greek Ruins: The Lion Gate

The Lion Gate of Mycenae holds a special place among ancient Greek monuments, as it is the only surviving monumental piece of Mycenaean sculpture and one of the largest Bronze Age Greek sculptures. It was built during the 13th century BCE, on the northwestern side of the Acropolis in Athens, marking the entrance to the fortified citadel of Mycenae. The name comes from the sculpture depicting two heraldic lions or lionesses that stand above the entrance. The lions most likely symbolize authority, power, or protection due to their position as guardians of the citadel. Moreover, their symbolic design may have also carried a combination of both religious and dynastic meaning in connection with Mycenaean elites.

Furthermore, it is the only relief image that was described in the classical literature of antiquity, making it known through literary descriptions before its archaeological discovery. As pointed out by the archeologist Fritz Blakolmer, Homer appears to have had in his mind these two lions when he wrote the description for the entrance to the Phaeacian palace of Alkinoos, decorated with two golden and silver guardian dogs, a masterpiece created by the artistry of the god Hephaestus. Additionally, Pausanias wrote a more accurate reference to this monument and its decoration.

Interestingly, research on the sculptures reveals evidence of foreign influence, as noted by Nicholas G. Blackwell. The relief was carved using tubular drills, pendulum saws, and convex hand saws. The over 340 drill holes and dozens of saw cuts made using these tools suggest that these stone working techniques, especially the pendulum saw and tubular drill, may have been borrowed from Hittite Anatolia. Therefore, there is a strong possibility that the sculpture was partly carved through a process of technological transfer between the Mycenaeans and the Hittites, through merchants, artisans, or other forms of shared knowledge.

Furthermore, analysis of the two lions suggests that they were not part of the initial design. Specifically, the lions had their heads turned backward and not forward. Signs of damage and restoration were also identified among the design changes. The lion’s tails are a prime example, as proven by the traces of mortar-like fillings made by Mycenaean artisans using lime-based substances to cover mistakes or deep cuts.

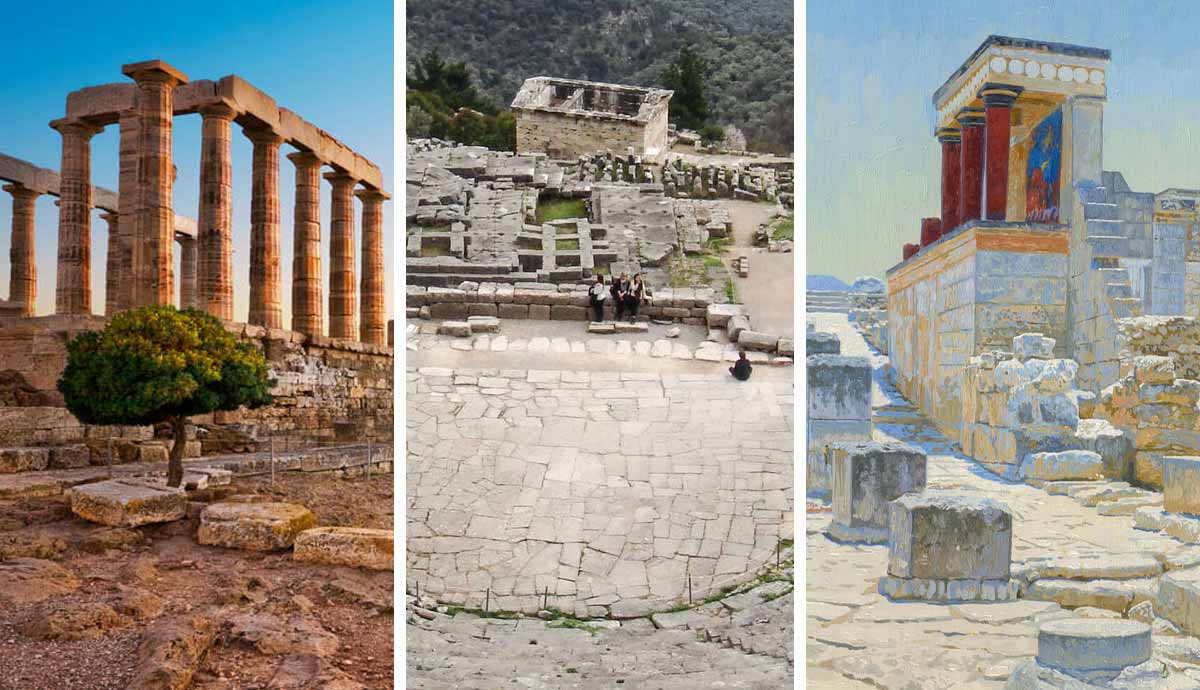

2. Ancient Theatrics: The Theater of Delphi

The theater of Delphi was built in the 4th century BCE, within the Pythian Apollo Sanctuary complex. It was modified several times, first in 160/159 BCE (during the time of Eumenes II of Pergamon) and later in the 1st century CE (during the early Roman Period), when it acquired the shape, we see today. Housing five thousand spectators, the theater offered a unique synesthetic experience due to excellent acoustics, thanks to a lack of enclosing walls (which prevented reverberation from outside), and its location above the sanctuary complex offered its spectators a breathtaking view of Phaedriades cliffs of Mount Parnassus.

In comparison with other theaters, the one in Delphi stands out culturally and historically. Besides plays, the theater also housed the Pythian games, musical contests, poetry recitals, and dramatic performances.

Its historical value further lies in its collection of wall inscriptions located near and within the theater. They detail the sales of slaves by their owners to the god Apollo. Specifically, this textual heritage chronicles the emancipation of over 1,200 individuals between 201 BCE and 100 CE. However, since Greek slaves did not receive citizenship upon being freed, the purpose of these contracts was to help slave owners replace an older slave with a younger one at a cheaper rate and help other owners to buy old slaves with less money.

3. More Theatrics: The Theater of Epidaurus

The ancient Theater of Epidaurus is located on Mount Kynortion, near Lygourio in Argolis, and was built in two phases during the late 4th century BCE, based on a plan designed by the architect Polykleitos the Younger. Like the theater of Delphi, this construction was part of a sanctuary complex dedicated to the ancient Greek God of medicine, Asclepius. It could house up to 14,000 spectators at a time, and due to its location, it also served as a backdrop for artistic, musical, and religious events associated with the worship of Asclepius. It stands out among other theaters of the period due to excellent acoustics, considered the best of its kind and still in use, hosting ancient drama plays and music festivals.

The theater achieved its harmony through a unique architectural design by Polykletos. He based the entire design of the construction on a single unit of measure, 0.35 m (13 inches, the radius of a central disk in the orchestra). Starting from this measurement, he conceived a series of radii and circles that defined every major part of the theater, such as the orchestra, the water canal, the auditorium, and the proedria. Correspondingly, these were employed to determine the length and depth of the stage and the layout of the annexes. Furthermore, his designs on the harmony also included the auditorium seating. He chose to ignore Vitruvius’s rule of constant seat incline in favor of a varied pitch between the lower and upper sets of seats. Therefore, spectators seated on the higher levels could enjoy a clear view of the orchestra due to the steeper upper slope.

4. The Royal Palace Complex at Knossos (Crete)

The impressive palace complex of Knossos is one of the world’s most important Bronze Age sites. Built on the hill of Kephala in Heraklion, it is arguably one of the oldest, if not the oldest, cities in Europe. It consisted of a central court, a main palace (belonging to King Minos according to myth), residential quarters, religious and ritual spaces, storage facilities, economic buildings (including shops and workshops), administrative spaces, a possible theater, and infrastructural elements (such as plumbing and ventilation).

Due to its importance as a major urban center and its long period of habitation (from the Neolithic period up until the 5th century CE), many legends are linked to this site, such as those of the mythical King Minos, Daedalus, Icarus, and the fabled labyrinth inhabited by the Minotaur. It was excavated in two phases: first in 1877 by Minos Kalokairinos, and later in 1900 by Sir Arthur Evans.

Two noteworthy aspects of this site are the architecture and the historical significance of the frescoes. The main palace had multi-story buildings with light wells and open-air courtyards, terracotta pipes for running water, flushing toilets, a drainage system, and a technique to mitigate damage from seismic activity. Builders used timber for its flexibility and ability to deform under stress without shattering, as beams integrated in walls and masonry. The frescoes are a valuable source of information for historians and archaeologists as they offer insight into the daily lives and beliefs of the Minoan civilization. These works of art depict religious festivals, rituals, sports, and decorative patterns and motifs. Furthermore, many frescoes from the palace walls depict the appearance of Minoans; although idealized, they are nonetheless important because they depict clothing and jewels.

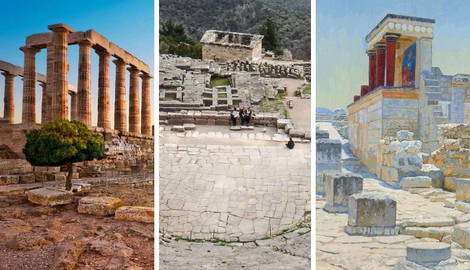

5. Wonder of the Greek Ruins: The Temple of Hephaestus

The Temple of Hephaestus (or Hephaisteion) is a Doric peripteral temple dedicated to Hephaestus, the Greek god of blacksmithing, and Athena Ergane, the patroness of crafts and workers. It is located at the top of the Agoraios Kolonos hill in Athens and was built between 460 and 420 BCE. Initially, the site was dedicated to the worship of general artisans, evidenced by the archeological discoveries of light metallurgy workshops and pottery workshops in the area. Furthermore, it hosted the yearly festival of Chalkeia, during which blacksmiths and artisans would parade their tools around the temple. After starting in the 7th century, the temple was used as a Christian church until 1834. As a result of its continuous use, it is considered one of the best-preserved ancient temples.

Besides its excellent preservation, the temple also houses impressive sculptural decorations called metopes (decorative panels located above Doric columns) that depict the feats of Herakles and Theseus. These can be found on 18 of the metopes—10 on the east side dedicated to Herakles, and 8 on the north and south flanks dedicated to Theseus. Curiously, the arrangement of both sets is irregular, and the sequence is out of order. The labors do not follow the traditional order. Cerberos is wrongly situated mid-series, and Theseus’ deeds are jumbled, not matching Plutarch’s version of the legend. Experts such as E. B. Harrison suggest that this situation resulted from an alteration of the sculptural program or that it was left incomplete during construction.

Further analysis of the aesthetic style suggests that the sculptors were influenced by the metopes of the Temple of Zeus at Olympia (featuring grotesque heads, caricatured monsters, and massive forms). However, the main difference is that the metopes at the Hephaisteion portray lighter, more agile bodies, similar to the style of the Parthenon. Therefore, the work of the sculptors at this site represents a transitional phase in classical sculpture—between the Severe Style and High Classical naturalism.