For centuries, merchants, generals, and statesmen contemplated how to connect the eastern and western parts of the Eurasian landmass. This dream led to the creation of the first Silk Road system in the late second century BCE to mid-third century CE. This system proved to be quite stable and lucrative, buoyed by Han China, Parthian Persia, and Rome. But long before this land-based bridge was built, the ancient Egyptians developed a much more efficient bridge that connected Eurasia, primarily by the sea. In the late second millennium BCE, the Egyptians built the first of several versions of a canal that connected the Red Sea to the Nile River. An examination of the classical historians and archaeological sources shows that the Egyptians primarily built the canal for trade purposes and that numerous versions of the canal were built, sometimes by non-Egyptians.

The Modern Suez Canal

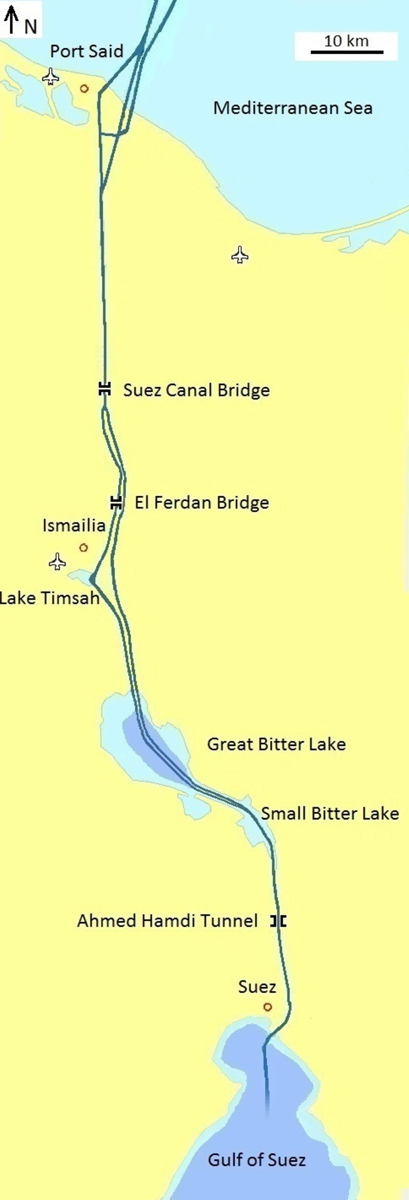

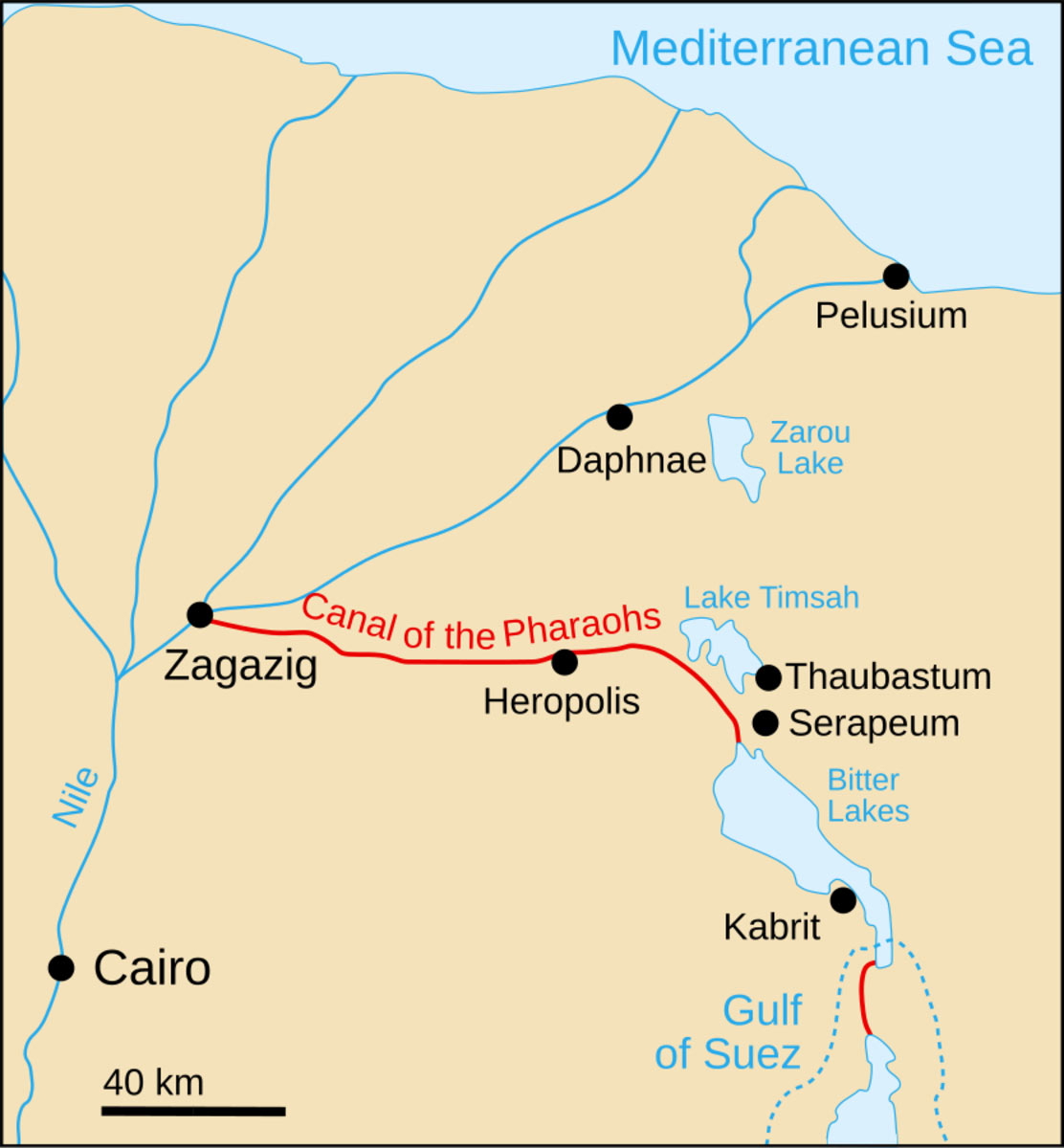

To understand the magnitude and importance of the ancient Red Sea Canal, it is important to briefly look at the modern Suez Canal. Completed in 1869, the Suez Canal is a modern marvel, cutting a 120-mile-long path through the 78-mile Isthmus of Suez. Unlike the ancient versions of the canal, the Suez Canal connects the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea directly. The Suez Canal was originally built and controlled by the French, but the British took control of it in 1882. A brief war was fought over it in 1956, with the British, French, and Israelis on one side and the Egyptians on the other. Today, the Suez Canal is a vital connection in global shipping, bypassing thousands of miles of the sea journey between Asia and Europe.

The purpose of the ancient Red Sea canals was essentially the same as the modern Suez Canal: to facilitate trade. There were also the added incentives of legitimatizing the rule of foreign-born kings and moving troops and diplomats from the Near East to the Mediterranean.

The Primary Sources

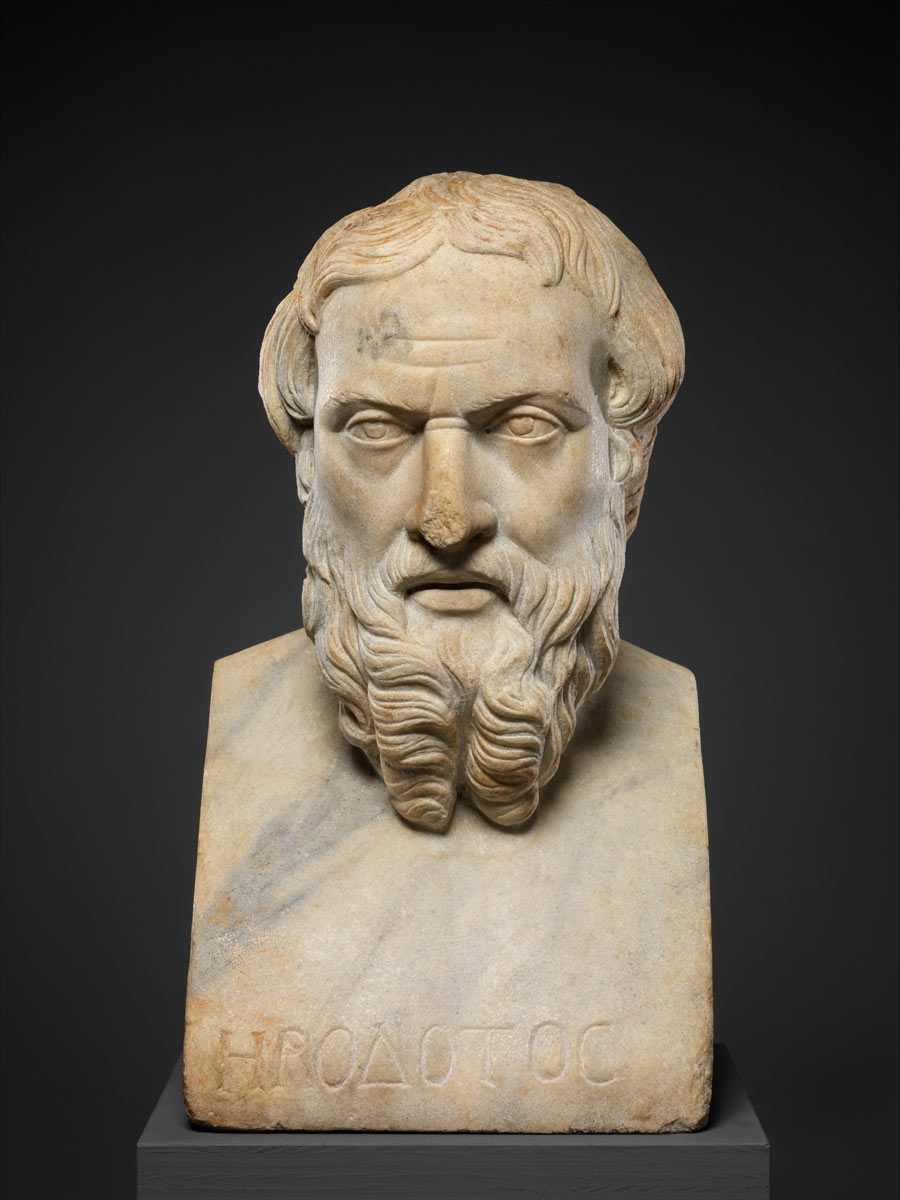

Nothing remains today of the ancient Red Sea Canal, also known as the “Canal of the Pharaohs.” However, there are a number of primary sources that attest to its existence. Among the most detailed are the accounts of classical historians and geographers, such as the 5th-century BCE Greek historian Herodotus. The 1st-century BCE Greek-Roman historian Diodorus and the 1st-century BCE-CE Greek-Roman geographer Strabo also wrote accounts of the canal. Overall, the authors corroborate each others’ accounts, but each also adds unique details that, although sometimes chronologically dubious, are quite helpful.

Classical sources are augmented by ancient Egyptian texts. Most of the Egyptian texts do not mention the Red Sea Canal specifically, although they do help to place the concept of pharaonic era canals into perspective. Finally, some archaeological artifacts can be compared with the written sources.

An Early Canal Project in the Middle Kingdom (c. 2055-1650 BCE)

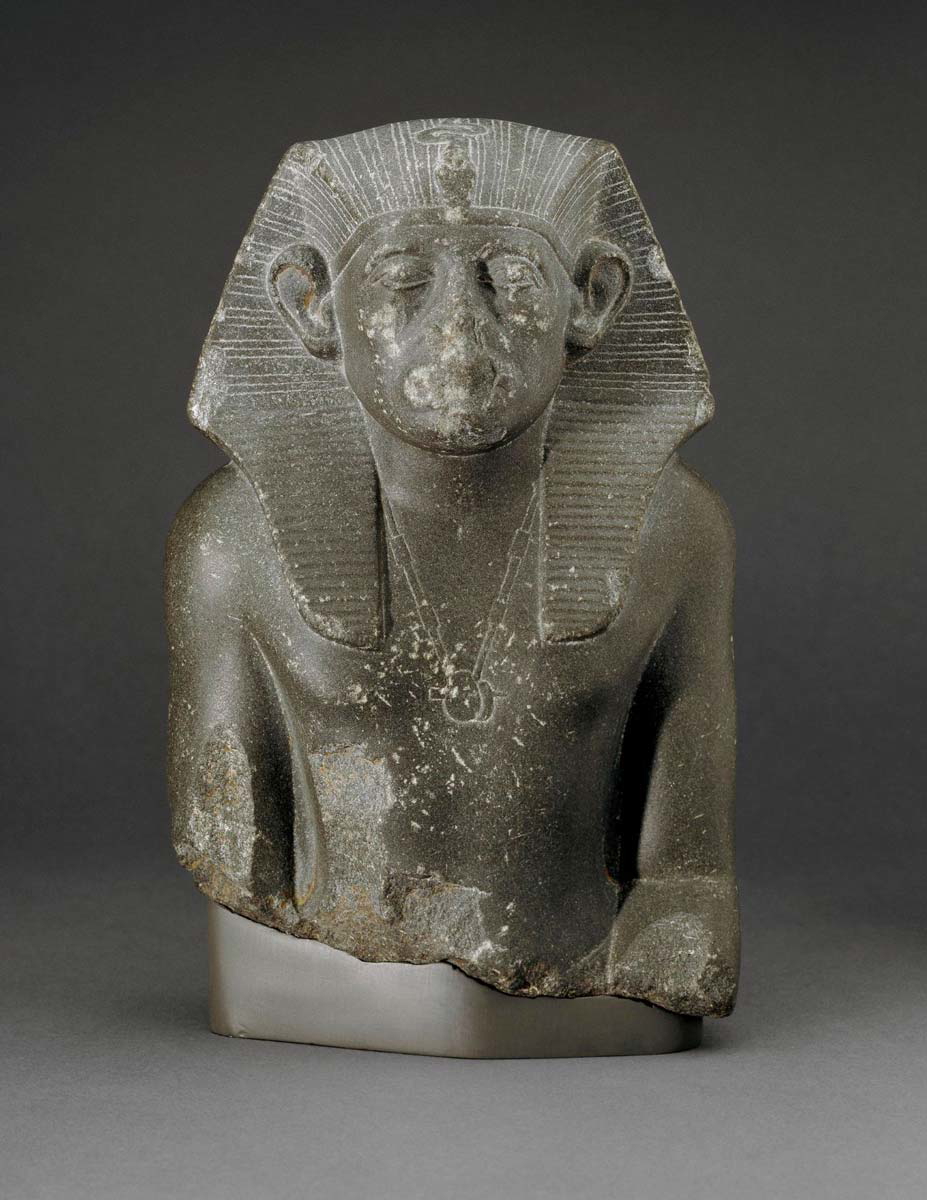

In Strabo’s passage about the Red Sea Canal, he states that “the canal was first cut by Sesostris before the Trojan War.” Sesostris was the name Greek and Roman historians generally applied to any of the three Middle Kingdom kings named Senusret. Many scholars place the historical Trojan War at around 1200 BCE, so the chronology is correct there, but can the claim be further corroborated? The Sesostris in this account, and most classical accounts for that matter, was probably Senusret III (ruled c. 1870-1831 BCE).

Because the classical historians could not read the ancient Egyptian language, they relied on Egyptian priests as their primary sources for Egyptian history. Senusret III was widely viewed by Egyptians of the Ptolemaic and Roman eras as one of the greatest pharaohs of their early history. His military campaigns into Nubia became legendary, as were his pyramid and a canal he built around the First Cataract.

The First Cataract of the Nile River was an important geographic location in ancient Egypt. First, it marked the cultural and political boundary between Egypt and Nubia. Second, although it marked the divide between Egypt and Nubia, the Egyptians wanted it navigable when they were the stronger of the two peoples. The Egyptians exploited Nubia for its gold, electrum, and other exotic goods from the African interior. Most of those commodities were hauled north by boats. So, as much as the First Cataract served as a vital barrier, it also needed to be free for trade. To accomplish this, the Egyptians built a modest canal around the cataract. The canal is mentioned in one of the historical annals of Senusret III. It was listed as about 221 feet long, 29 feet wide, and 22 feet deep.

“Year 8 under the majesty of the King of Upper and Lower Egypt: Khekure, living forever. His majesty commanded to make the canal anew, the name of this canal being: ‘Beautiful-Are-the-Ways-of-Khekure-[Living]-Forever,’ when his majesty proceeded up-river to overthrow Kush, the wretched. Length of this canal, 150 cubits; width, 20; depth, 15.”

Canals in the New Kingdom (c. 1550-1069 BCE)

The First Cataract Canal was later re-dug by the New Kingdom pharaohs, Thutmose I (ruled c. 1504-1492 BCE) and Thutmose III (ruled c. 1479-1425 BCE). But even more important was the mention of a series of canals during the reign of Merenptah (ruled c. 1213-1203 BC). An inscription on the walls of the Karnak Temple dated to the reign of Merenptah relates how two interconnected canals played a role in the defense of the land from the Libyans. A damaged part of the inscription mentions the “Sheken canal” and the “Eti canal.” The Papyrus Harris, which was written during the rule of Ramesses III (reigned 1184-1153 BCE), mentions a “canal administration,” suggesting that by the late New Kingdom, the Egyptian canal system had become quite intricate. With that said, a canal that connected the Red Sea to the Mediterranean Sea was never explicitly noted before the Late Period.

The True Red Sea Canal in the Late Period (664-332 BCE)

It is possible, and arguably probable, that the Egyptians built a series of canals that linked the Red Sea to the Mediterranean Sea. While it is, for the most part, conjectural, there is evidence that several canals were built during the Late Period. According to Herodotus, the 26th dynasty king, Nekau II (ruled 610-595 BCE), commissioned the construction of a canal that connected the two seas. Part of the account reads:

“It was Necos who began the construction of the canal to the Arabian gulf, a work afterwards completed by Darius the Persian. The length of the canal is four days’ journey by boat, and its breadth sufficient to allow two triremes to be rowed abreast. The water is supplied from the Nile, and the canal leaves the river at a point a little south of Bubastis and runs past the Arabian town of Patumus, and then on to the Arabian gulf. The first part of its course is along the Arabian side of the Egyptian plain, a little to the northward of the chain of hills by Memphis, where the stone-quarries are; it skirts the base of these hills from west to east, and then enters a narrow gorge, after which it trends in a southerly direction until it enters the Arabian gulf. The shortest distance from the Mediterranean, or Northern Sea, to the Southern Sea—or Indian Ocean—namely, from Mt. Casius between Egypt and Syria to the Arabian gulf, is just a thousand stades. This is the most direct route—by the canal, which does not keep at all a straight course, the journey is much longer.”

This was later corroborated by Diodorus to some extent, but he added that the Persian king Darius I (reigned 522-486 BCE) took over the project. Interestingly, Diodorus wrote that “Darius the Persian made progress with the work for a time but finally left it unfinished.” The reason given was that he was informed such a project would cause massive flooding of the Delta. Despite this account, other sources suggest the Persian king did complete the canal.

A collection of stelae dated to the reign of Darius I, known collectively as the “Red Sea Stelae,” appear to corroborate Herodotus’s account. The best preserved are three badly damaged ones that were discovered near Tell l-Maskhoutah, Egypt, in 1889 by Wladimir Golénscheff. The stelae were then transported to the Egyptian Museum, Cairo, in 1907, where they were translated and examined by Egyptologists and other Near Eastern scholars. The stelae are clearly dated to the reign of Darius, but there is some debate about exactly when they were completed and if Darius was in Egypt when the canal was opened. The syntax of the actual text and the spelling of Darius’s name closely match that of a colossal statue of the king that was discovered in Susa in 1972. Although relatively short, the texts on the stelae offer more insight into details about the canal.

The best preserved of the three stelae is a granite stela discovered near Shaluf, known as the Shaluf stela. One side is written in Egyptian but is so damaged that a translation is nearly impossible. The most important aspect of this stela is the trilingual cuneiform text on the opposite side of the Egyptian text. The non-Egyptian texts are written in six lines in Old Persian, four lines in Elamite, and three lines in Akkadian. The non-Egyptian texts read the following:

“Saith Darius the King: I am a Persian; from Persia I seized Egypt; I ordered this canal to be dug, from the river by name Nile, which flows in Egypt, to the sea which goes from Persia. Afterwards this canal was dug thus as I commanded, and ships went from Egypt through this canal to Persia thus as was my desire.”

The Red Sea Canal stelae appear to corroborate the classical accounts, and vice versa, with Darius claiming he completed the canal. Based on where the stelae were discovered, it would appear that the canal followed the route Herodotus noted. It went from the Red Sea to the Bitter Lakes before turning west to meet the Pelusiac Branch of the Nile River. The purpose was clearly to move troops and trade from the east to the west.

Ptolemy II and the Final Version of the Ancient Red Sea Canal

The classical sources corroborate the archaeological evidence to a certain degree. Although both Diodorus and Strabo wrote that the canal was completed, they credited the Ptolemaic-Egyptian king, Ptolemy II (ruled 284-246 BCE), with the feat. Strabo, perhaps based on Herodotus, wrote that Psamtek I (reigned 664-610 BCE) began construction of the canal, which was followed up by Darius I. Ultimately, one or more of the Ptolemaic kings then finished the project.

“The Ptolemaïc kings, however, cut through it and made the strait a closed passage, so that when they wished they could sail out without hindrance into the outer sea and sail in again.”

Diodorus offered a slightly more detailed account of the completion of the canal, crediting Ptolemy II. He also assigned the canal’s terminal or starting point, depending on the direction of the journey, as the Red Sea city of Arsinoe.

“At a later time the second Ptolemy completed it and in the most suitable spot constructed an ingenious kind of lock. This he opened, whenever he wished to pass through, and quickly closed again, a contrivance which usage proved to be highly successful. The river which flows through this canal is named Ptolemy, after the builder of it, and has at its mouth the city called Arsinoë.”

When all the classical accounts, Egyptian and Persian texts, and archaeological evidence are considered together, it appears that the Red Sea Canal was the culmination of centuries of experiments. The Egyptians began building canals in the Old and Middle Kingdoms, and by the New Kingdom, they had become experts in the technology. They possibly built the first version of the Red Sea Canal in the New Kingdom.

There is better evidence that the Egyptians completed the canal in the Late Period, and then foreign rulers probably re-cut the earlier version. Ptolemy II was known for making Alexandria the center of the world, completing projects started by his father, and drawing scholars to the city. Therefore, it is likely that Ptolemy II thought it was vital to connect Egypt to the west and east via the Red Sea Canal.