The antiquities we see in museums today did not get there by accident. Across five centuries, a small number of antiquities collectors determined what survived the ages, what scholars studied, and what the pubic came to know as “classical.” This list comprises 10 historical antiquities collectors whose choices continue to shape museum and gallery displays worldwide.

10. Lorenzo de’ Medici (1449–1492)

The Medici family was a banking dynasty that ruled Florence beginning in the 15th century. Their wealth and politics turned art into civic identity. Under Lorenzo the Magnificent, the city became a center for the study of antiquity. He expanded the Medici family library with Greek and Latin manuscripts, assembled coins and engraved gems, and invited artists and scholars to study antique models at close range.

The young Michelangelo learned from the objects that Lorenzo had gathered. By utilizing antiquities to educate the public, project their taste, and legitimize their rule, the Medici established a template that later courts, museums, and antiquities collectors followed.

Where is the collection today? It is dispersed among the museums and palaces in Florence, including the Uffizi Gallery, the Pitti Palace, and the Medici Chapels.

9. Pope Julius II (ruled 1503–1513)

During the Renaissance, Pope Julius II used art and architecture to project papal authority and remake Rome. His court gathered classical marbles in the Belvedere Courtyard and opened them to artists and scholars.

By compiling masterpieces such as the Laocoön and the Belvedere Torso into a single accessible setting, Julius II cemented Rome as an educational hub for artists. The Vatican display became an important model for sculpture galleries as we know them today, as well as a standard for museum education.

Where is the collection today? The classical marbles associated with Julius II are housed in the Vatican Museums, specifically in the Belvedere Courtyard and the Pio-Clementino Museum.

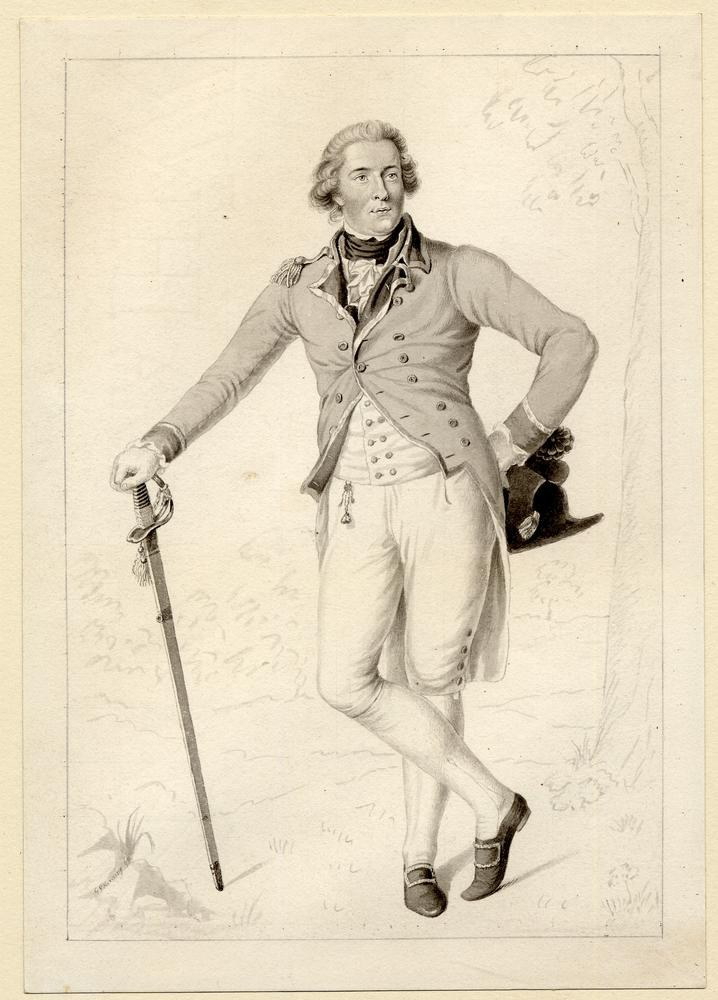

8. Lord Elgin (1777–1841)

Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin, served as British ambassador to the Ottoman Empire from 1799 to 1803. He viewed global antiquities as potential cultural assets for his home nation. Most infamously, Lord Elgin arranged the removal and shipment of Parthenon sculptures and other Athenian antiquities from Ottoman Greece to London.

The installation of these antiquities in the British Museum helped shape how global museums narrate classical Athenian history. At the same time, the so-called Elgin Marbles often center in modern-day debates on repatriation. While Greece seeks the return of the Parthenon sculptures to their place of origin, the British Museum cites preservation arguments and historical permissions.

Where is the collection today? Most of the Parthenon sculptures removed by Elgin are currently on display at the British Museum in London.

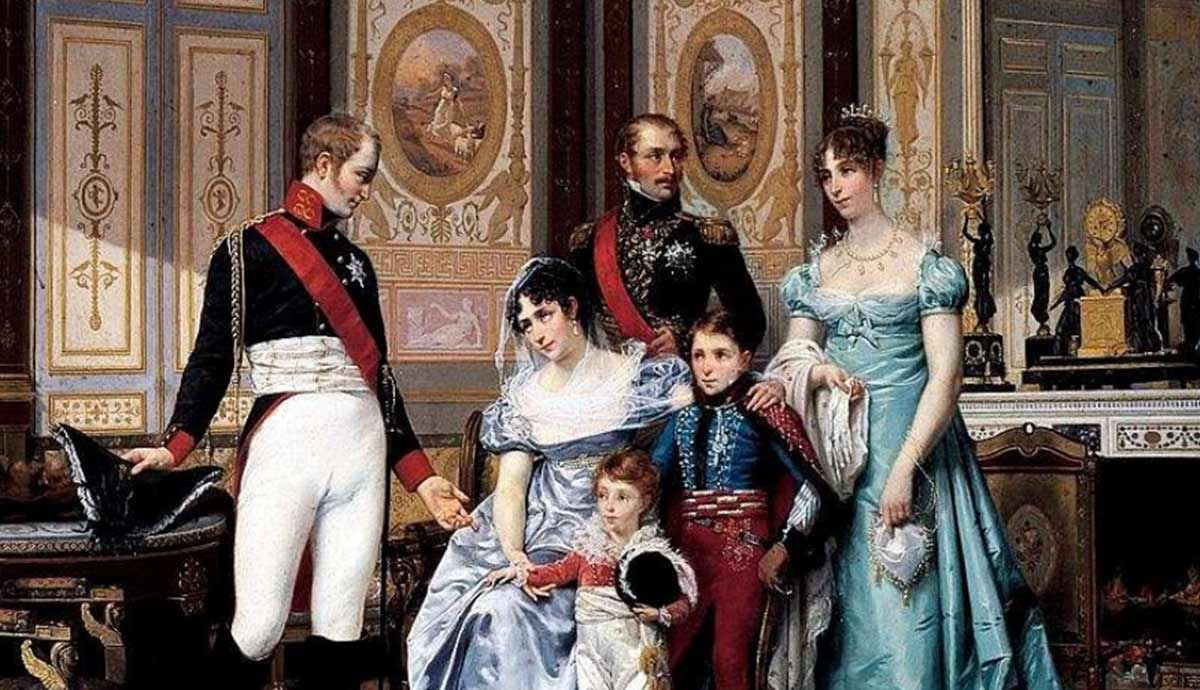

7. Napoleon Bonaparte (1769–1821)

From 1798 to 1801, Napoleon Bonaparte‘s army campaigned in Ottoman Egypt and Syria. The venture ended in military defeat, yet it produced a surge of cultural and scholarly knowledge, including the discovery of the Rosetta Stone, and laid the foundation for the field of Egyptology.

Napoleon brought along a large team of civilian scientists and scholars to survey temples, record inscriptions, and catalog objects. Their work appeared in the multivolume Description de l’Égypte (1809–1829), an encyclopedic record that standardized methods of documentation and shaped how museums research and present Egyptian collections.

The Napoleonic invasion also sparked a competition between Britain and France to secure Egyptian antiquities for their national museums, a race that continued throughout the nineteenth century. This legacy is visible today at the British Museum in London and the Louvre Museum in Paris.

Where is the collection today? Key objects and documentation are dispersed. Major Egyptian holdings from the collection are displayed in the Louvre and the British Museum. The Description de l’Égypte is held in research libraries and available in digitized editions.

6. Sir William Hamilton (1730–1803)

From the 1760s, Sir William Hamilton, Britain’s ambassador in Naples, amassed an unparalleled collection of Greek vases, bronzes, gems, and sculptures. He acquired works through Campanian excavations and local dealers, then invited scholars and travelers to view them privately in his palazzo.

Hamilton’s method of cataloging served to standardize the study of pottery. His catalogs grouped works by shape and fabric, named techniques such as black-figure and red-figure, recorded provenance and measurements, and interpreted scenes, treating imagery as evidence for myth, ritual, and daily life. Museums and antiquities collectors have since adopted this framework as a template for labels, case groupings, and catalog records.

Where is the collection today? Major groups of Hamilton’s vases and related antiquities are held at the British Museum in London.

5. Catherine the Great (1729–1796)

Catherine the Great, Empress of Russia from 1762 to 1796, positioned herself as an Enlightenment monarch. She tirelessly acquired classical sculpture, engraved gems, coins, and entire cabinets through agents. These works were inventoried and installed in purpose-built rooms of the Small and Old Hermitage, adjacent to the Winter Palace, establishing procedures for cataloging and curating antiquities.

Catherine commissioned dedicated antiquities galleries in the Small Hermitage and the Old Hermitage, located near the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg. Her successors expanded access to the royal collection, and in the nineteenth century, the New Hermitage opened to the public as a museum. The classical core that visitors see today still rests on Catherine’s acquisitions and the cataloging and display systems she established.

Where is the collection today? The classical collections Catherine assembled anchor the State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, Russia.

4. Sir John Soane (1753–1837)

Sir John Soane, the son of a bricklayer, entered the Royal Academy’s School of Architecture in London at age 18 in 1771. After a Grand Tour of Italy, focused on close study of ancient sites and antiquities, he established an architectural practice and won major commissions, including the Bank of England.

Soane’s passion for antiquities grew into one of the most significant collections in the world. In 1792, he purchased two neighboring homes in London. Over the following decades, he rebuilt and extended them to house his ever-growing collection of antiquities, furniture, and sculptures. Soane eventually bequeathed his property and collection to the nation as a public museum. Sir John Soane’s Museum remains open today, its rooms arranged much as he left them.

Where is the collection today? Soane’s collection is preserved at Sir John Soane’s Museum, located at 12–14 Lincoln’s Inn Fields in London.

3. The Torlonia Family (18th century—present)

Beginning in the late 18th century, the Torlonias rose to prominence in Rome. Giovanni Torlonia administered Vatican finances and earned titles that secured ducal and princely status. Collecting antiquities became a central part of that identity.

They acquired sculptures through dealers, bought entire collections from indebted noble houses, and excavated finds on their estates. The result was a vast private trove, often ranked among the most important collections of Roman marbles, including busts, statues, reliefs, sarcophagi, and portraits.

In 18,75 Alessandro Torlonia opened a museum for the marbles, though access was limited to invited visitors. While many works were off view, family catalogues and photographs became standard references, shaping attributions and typologies for decades. In the 21st century, conservation projects and exhibitions returned selected pieces to public view, refreshing those benchmarks and influencing gallery displays of Roman portraiture and sarcophagi.

Where is the collection today? The marbles are held by the Fondazione Torlonia in Rome, with selected works shown in recent conservation projects and temporary exhibitions.

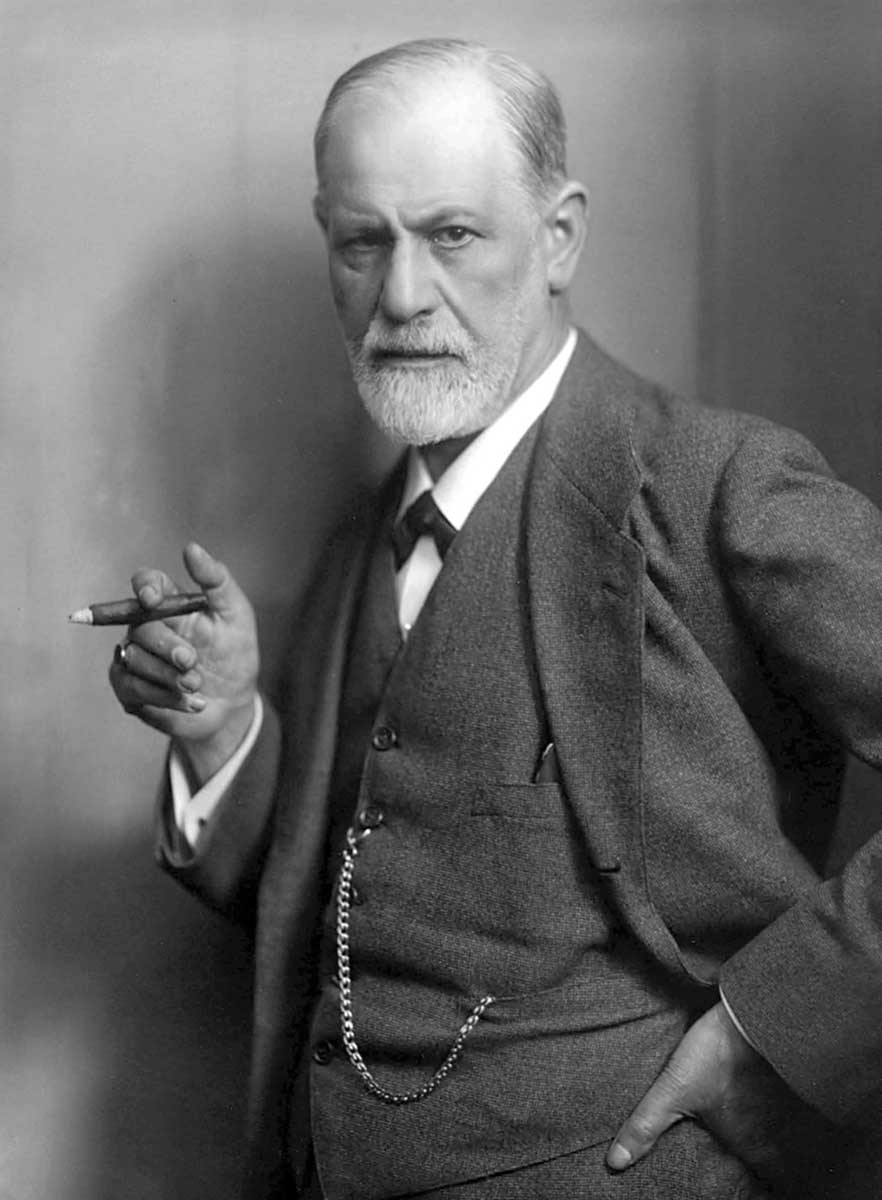

2. Sigmund Freud (1856–1939)

Alongside his groundbreaking work in psychoanalysis, Sigmund Freud compiled a significant personal collection of antiquities. When he left Vienna for London in 1938, the collection numbered over 2,000 pieces. Its range was broad—from Egypt, Greece, and Rome to India, China, and Etruria.

Freud began by collecting plaster replicas, then transitioned to originals, including funerary stelae, painted ceramics, and small statuary. He arranged many of these in his personal study, demonstrating how antiquities influenced his philosophies on myth, memory, and ritual. A Roman Athena held particular significance for him and accompanied him into exile from Nazi-occupied Austria.

Today, the Freud Museum in London preserves his study largely as it was when he left it. The collection demonstrates how small antiquities can support timeless ideas, and why cross-cultural holdings are important for tracing universal themes.

Where is the collection today? Freud’s antiquities and study are primarily preserved at the Freud Museum in London.

1. Charles Towneley (1737–1805)

Charles Towneley, a wealthy English country gentleman, became one of Britain’s leading collectors of antiquities in the 18th century. Portrait heads, reliefs, mythic figures, and large marbles decorated his London house, where entire rooms were arranged for the comparison and study of antiquities.

Many pieces in Towneley’s collection originated from excavations around Rome, including sites associated with Hadrian’s Villa at Tivoli. Towneley kept notes on provenance and restoration and commissioned drawings that helped scholars identify subjects and workshop styles. Several sculptures in museums around the world still carry his name in the literature.

After Towneley died, the British Museum acquired a significant portion of his collection. The Towneley marbles anchor core galleries and serve as benchmarks for Roman copies of Greek originals, eighteenth-century restoration practice, and the history of collecting. They demonstrate how a private gallery has become a public standard for interpreting Roman sculpture today.

Where is the collection today? A substantial portion of Towneley’s marbles is in the British Museum in London, where they remain integral to the Greek and Roman sculpture galleries.