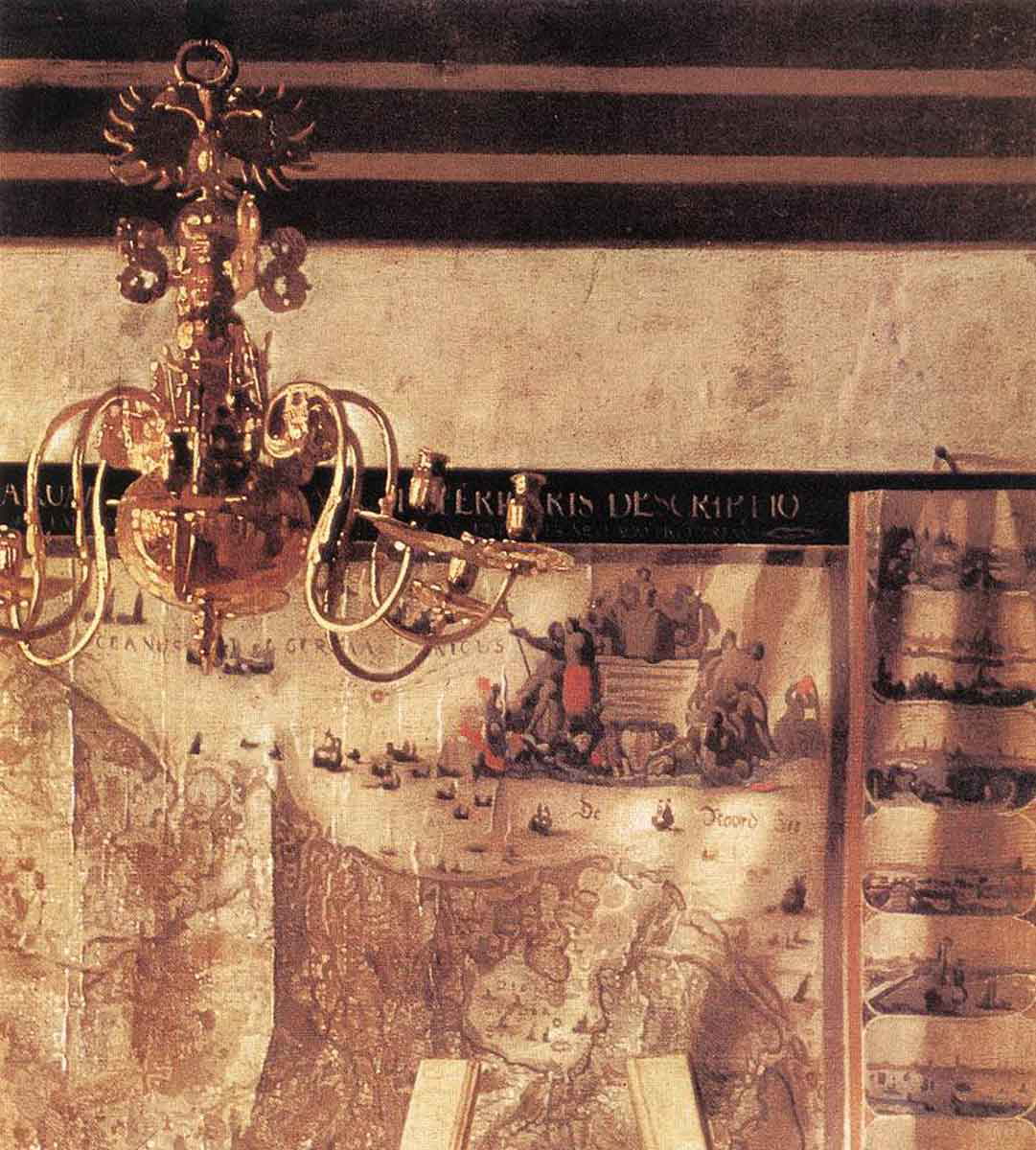

Vermeer’s work The Art of Painting, which he completed around the year 1668, is a complex image. It can be both viewed and “read” because, as well as being notable for rich tonal and textural effects, it is an allegory that highlights the proper aims and the necessary learning that enables an artist to become worthy of praise. In this image, Vermeer claims a high noble status for painting as a liberal art, for the best painters, and himself.

The Art of Painting

The artist paints himself in the act of painting a portrait of his daughter in a room richly furnished with various artifacts and paraphernalia. The artist is Johannes Vermeer (1632-1675), and the room is one he has painted many times: the front room on the second floor of his mother-in-law’s house in Oude Langedijk in the Netherlands.

Today, Vermeer is considered a canonical artist, a jewel in the crown of the Dutch “Golden Age” of painting. In his own time, indeed, he had garnered relative fame. However, between his own time and the 19th century, his mark on the history of art had all but vanished. This was a result of his being omitted from several important treatises on Dutch art over several centuries. Then, in the mid-19th century, French art critic Théophile Thoré-Bürger resurrected the reputation of the Dutch master, which has continued to thrive ever since.

Vermeer painted mainly genre scenes, or scenes from everyday life. He worked slowly and methodically and, because of this, produced relatively few completed paintings. The Art of Painting (c. 1666-8), however, is one of only two known allegorical paintings in Vermeer’s œuvre. As such, it is more overtly layered in terms of meaning. For each seeming moment of the factual, there is another level of signification. In this sense, the scene can be read as both a genre painting and a genre painting that points beyond itself. In the words of art historian Albert Blankert: “No other painting so flawlessly integrates naturalistic technique, brightly illuminated space, and a complexly integrated composition.”

Visuality and Readability: The Textual Image

The Greek historian Plutarch wrote: “Simonides calls painting silent poetry and poetry painting that speaks.” This comment seems especially apt for Vermeer’s The Art of Painting which has also been titled Allegory of Painting. Once we dig into the picture’s meaning, we find a counterbalance or complementarity between the visual and the textual. For instance, the young model in the left background holds a trumpet and wears a wreath. Scholars have identified three possible allegorical personages that she could represent, and these are mutually reinforcing; therefore, Vermeer may have meant to represent all three. The three Muses are Clio, the Muse of History, Fama, of fame, and Pictura, painting.

The still life Vermeer paints in the left foreground—the chair and table holding a plaster cast mask and folio—is an introduction to the viewer of the image but also refers to the artist’s introduction to their craft: the study of antecedent models and texts, be they literary or scholarly. Yet, the depicted painter, Vermeer’s analog, is solely addressed to the painting of his model as Muse. Clio, the model, holds a volume of the Greek historian Thucydides, signifying that the learned attain fame; as Fama, she holds her trumpet; and, as these two as well as Pictura, she wears her wreath of honor.

Vermeer’s genre painting, therefore, becomes a painting of the painting of history. It is not so much in the tradition of the istoria—the painting of historical or mythological events—but is a picturization of the ideal motivations of momentous deeds, and of the consequent memorialization of their actors that is central to the istoria tradition. On the painter’s panel within the picture space, only the wreath is painted, showing the ideal motivations of the artist. It is a conferral of fame onto the art of painting itself by the artist. However, given the long apprenticeship and laborious effort referred to by the foreground passage of the table holding artifacts of learning and practice, only the most technically proficient and learned artists can partake in the fame of painting.

Scholar Hessel Miedema has observed in Vermeer’s image that the concept of istoria is signified on three levels. Firstly, the model is portrayed as Clio, secondly, it shows the idea that a history piece is worthy of the highest accolade in art, and thirdly the painting itself is an example of such a history piece.

Vermeer paints the artifacts on the table as an example for artists to emulate and for viewers to delight in. The viewpoint for the spectator, just below the trumpet of fame, also signals the coming together of artist and spectator in their work and learning, respectively, to the degree that the viewer too becomes worthy of being celebrated. This is in line with the meliorism that pervaded Dutch society in the 17th century, as the age of self-improving mercantilism superseded that of the hereditary aristocracy.

Thus, there are various transfigurations in the picture. The visual is freighted with textual significance. The young model is transformed into a Muse, the artist with his rich apparel is transformed into a possessor of a new self-made nobility (both of social status and the soul), the humble genre painting of everyday life becomes history painting, and learning and work add up to lasting fame.

Vermeer paints the painter painting the wreath. It is conferred on the painting, on himself, and the vocation of painting as a liberal art. Vermeer’s overlay of allegorical meanings shows him self-consciously as the archetypal and ideal humanist artist-scholar. He has mastered technical illusionistic representation just as he has mastered the mechanics of symbolic reference—the visual made textual. Thereby, Vermeer has made his image poetic and his poetry visible in the spirit of Plutarch’s Simonides.

Ivan Gaskill has observed that Vermeer’s later art revealed an “increasingly abstracted, tonal approach to painting.” This is also true of The Art of Painting. This characteristic conveys the immateriality of the ideals of artistic and moral perfection that Vermeer sought to at least imply. However, there is a tension here as he does this through a poetical naturalism that makes for an illusionistic coherence at the same time as admitting a looser paint application, as on the curtain. This suggests to the imagination an artistic aspiration beyond the factual truth of naturalism and the genre scene.

Therefore, Vermeer is matter-of-fact in terms of composition and its elements while achieving an unseizable pictorial world (visually and in his painting of an ideal). He heightens the light falling on Clio and exploits the shadows of the room with subtle and muted colors to create an image that shimmers like a mirage.

Vermeer’s orchestration of the light in the scene is telling. The direct light source—the window of the left background—is screened from us, the viewers. Only the depicted painter and the Muse have direct access to it. The Muse—be she Clio, Pictura, or Fama—is bathed in its golden glory while the depicted painter both pays tribute to this glory in the act of painting and participates in it through Vermeer’s masterly treatment of the overall painting. There is in this both effortless inspiration and the dogged, effortful capturing of it on the canvas. As such, Vermeer is highlighting the moral and artistic virtue of work.

Miedema also refers to this moral element by correlating the art of rhetoric with the picture. As part of his analysis, “reading” as well as looking at the image, he refers to the dichotomy of inspiration and work. He writes of natura being signified by the Muse and of the rhetorical exercitatio as referring to the painter at work.

Miedema is explicit that the Art of Painting is analogous to the “art of living” in the painting. He even sees a contrast between the impermanence of fame and the immortality of virtue, with the painter becoming in this context a moral exemplar partaking in the latter. This perhaps overstates the matter. Vermeer certainly inscribes a moral component to his vision, however, there is no pictorial evidence that he divides fame from virtue. If anything, he paints fame as dependent on virtue, and virtue as the path to fame. There does not appear to be a note of the polemical in the painting that would derogate “mere fame” for the sake of virtue because the image in its thorough idealism extols both.

Vermeer seems to conflate three types of nobility in the painting. The richly dressed artist has a social nobility; the nobility of virtue is incontestable and can be earned through endeavor, and the process of the visual rendering of these is an example of that earned nobility of soul. The model is sanctified as a Muse, the painter ennobled by learning and the choice of allegorical subject, while the viewer is ennobled by Vermeer’s seemingly exacting naturalism.

Naturalism and Artifice

Vermeer is often remarked upon for having achieved a complete naturalism of representation, particularly in his handling of light. But as Michael Zell has shown, the artist was acutely aware of a tension inherent in representation. Zell writes of Vermeer’s “insistence on the equivocal nature of pictorial illusionism.”

Zell goes on to write of Vermeer’s use of tone and light over the more conventional modeling of form “at the expense of resolution and even of credibility.” Zell is remarking here on Girl with a Pearl Earring, but his comment is also on the whole descriptive of The Art of Painting. Vermeer’s orchestration of light in the latter painting—restricting the sunlight to the left background—allows him to create an atmosphere of gradated shadows in the rest of the picture.

The tactility of the scene in these shadows is both asserted and denied. It is replete with objects, especially those on the table, which are close to the viewer, heightening the sense of the tactile. Yet, the clothing of most of the scene in these indistinct and varied lighting conditions serves to dematerialize these objects, even the figure of the artist to some degree. This all serves the left background scene where direct golden light falls on the Muse. It is as though Vermeer paints his objects and himself as mere intermediaries to the artistic and moral ideal.

That is not to say, however, that Vermeer does not luxuriate in various textural effects—from plaster mask to panel to the map on the background wall. But the light being restricted to Clio at the window is his prime moment in the composition. It is indicative of both naturalism and artifice. It is painstakingly and poetically painted, as well as the very poetry of his painting of light draws attention to the fact of its being a representation.

The chandelier seems important in this context. Just as Clio is bathed in natural light, the chandelier is pointedly devoid of candles and in the shade. This can be interpreted as a self-deprecating moment to the effect that, for all Vermeer’s genius for light and hue on display, the artifice of representation cannot compete with the experiential truth of light on the senses.

Vermeer’s artifice is thus self-conscious. There is even artifice within the artifice. The model is Clio. The form of the plaster mask is painted, the chandelier is in shadow, the wreath on the painted panel is also painted, and finally, the seemingly trompe-l’oeil curtain that “reveals” the image is painted. Therefore, the painting appears to be closer to a conjuring of the mind than a representation of reality, for all of its vividness. It is a representation of representation.

The triangular passage from the empty chair to the artist to the Muse is perhaps an instruction to the artist. It can be seen as a warning to represent reality, or an ideal, rather than the mere imitation of past masters.

The contemporaneous art theorist Samuel van Hoogstraten (1627-1678) advised the landscape artist to paint nature’s “thousand refracted colors.” Vermeer adapts this to his “genre” scene here. His manifold hues are achieved within the limits of a seeming tonal polarity—between sober sunlight and the shadowy studio space. Examples of this are in the undulating hues across the creased map on the wall, the gilt highlights and colored shadows on the upper part of the chandelier, and the reds on the right side of the tiled floor. It is also in Vermeer’s variations on his favorite blue, from lending cold weight to the curtain to the highlighted turquoise of Clio’s robe. Perhaps even the neutral dark of the painter’s doublet jacket establishes the artist as the impartial observer and portrayer of forms and the intricacies of light in a naturalistic manner.

Writing in 1721, French artist and theorist Antoine Coypel insisted that true art hides art, as its objects appear arranged by chance. The Art of Painting amounts to a complication of this dictum. Vermeer draws attention to art. From his deprecation of representation, and perhaps his means of representing, to the overt references to the long study needed to attain the status of a liberal artist, the picture foregrounds the limits of pictorial imitation as well as its glories. The painter at his easel, the model as an allegorical figure, and the curtain, all index art itself. However, in the expert handling of naturalistic light from the window, the naturalism of the liberal art still life on the table, and the overall seeming effortlessness of Vermeer’s technical effects of tone and hue, art is hidden too. Perhaps one could amend Coypel’s recommendation of art hiding art to, in Vermeer’s case, effort hiding effort.

Bibliography:

Harrison, Wood, Gaiger (eds), Art in Theory: 1648-1815: An Anthology of Changing Ideas.