Summary

- The Ancient Athenians developed early banking systems that were adopted by their Greek allies.

- This Athenian model influenced Hellenistic kingdoms, notably Ptolemaic Egypt, which introduced state and private banks.

- Romans adapted Greek banking concepts and created an expansive international banking system.

- Roman banking eventually collapsed due to economic crises. Banking reemerged in Europe during the Crusades.

Modern Western culture is indebted to the ancient Greeks and Romans in many ways. Writing, religion, government, and art in medieval Europe were all inspired by the Greeks and Romans. Banking is another concept that originated in the Hellenic world. The Athenians developed a sophisticated banking system in the 5th century BCE that influenced economies throughout the Greco-Roman world. Hellenistic kingdoms adopted Athenian banking, and later the Romans expanded upon this system with their own monetary theories. Roman banking largely collapsed at the end of the 3rd century CE due to internal crisis and the emergence of Christian views on usury and banking. Large-scale banking would only re-emerge in Europe during the Crusades.

The Treasury of the Delian League

In the years between the Greco-Persian Wars (499-449 BCE) and the Peloponnesian War (431-404 BCE), Athens became the premier Greek city-state. The Athenians achieved their status through a combination of shrewd political moves, naval prowess, and effective economic policies.

Control of the Delian League was another crucial component of Athenian hegemony in the Hellenic world. The Delian League began as an anti-Persian alliance of Greek city-states in 478 BCE, during the latter stages of the Greco-Persian Wars. Although Athens was the leading state in the league, the ships and gold the alliance collectively used were initially held on the island of Delos. Other prominent cities, such as Delphi and Olympia, had significant sanctuaries that were also notable treasury houses. These early temple-treasury hybrids were safehouses for various goods, including votive offerings, cult statues, weapons, gold, and silver. The shrewd Athenian statesman Pericles (495-429 BCE) saw great economic potential in this system, so he decided to move the Delian League’s treasury to Athens in 454 BCE.

When Pericles and the Athenians took control of the Delian League’s treasury, Athens began to exert significant influence over other Greek economies. The Athenians decreed that their allies would adopt Athenian coins, weights, and measures, thereby elevating Athens’ economic position in the Greek world. The move also meant that the cult of Athena essentially became the Bank of Athena.

The Bank of Athena

The Parthenon in Athens was another achievement of Pericles, built during his tenure as strategos of Athens. Dedicated as a temple for the city’s patron goddess, Athena, the Parthenon also began operating as a bank during the Peloponnesian War. The 5th-century BCE historian Thucydides described how the Delian League’s war effort was funded by this Bank of Athena.

“Their strength came from the financial income they paid and that, for the most part, success in war was a matter of judgment and abundant revenues. He told them they could take confidence, since six hundred talents in tribute usually came in every year from the allies apart from other revenue, and on the acropolis there was still six thousand talents in coined silver remaining at that time (the largest amount had been nine thousand seven hundred, from which they had made expenditures for the gateway of the acropolis and the other buildings as well as for Portiada) and, apart from that, uncoined silver in private and public dedications, and there was all the sacred equipment for processions and contests and booty from the Mede and everything else of that sort, not less than five hundred talents; going further, he added the considerable amount from the other sanctuaries.”

Bullion from the Parthenon, as well as golden statues, were used to mint coins, but the banking activities of the Athena Temple were not limited to holding and minting currency. The Temple made interest-bearing loans for secular purposes, which it used to fund the war effort and building projects. The administrative structure of the Bank of Athena quickly began to resemble a modern bank.

Another decree from the Athenian authorities established a board of treasurers who oversaw operations of the Athena treasury. The board of treasurers managed all aspects, not only of the Athena bank, but also the treasuries of the other local sanctuaries. The records indicate that each deity had property and funds assigned to them that were listed separately.

The Athenian banking system was efficient and effective in the early stages of the Peloponnesian War, but this did not endure. As the Spartan-led Peloponnesian League gained the upper hand, the Athenian banking system began experiencing significant monetary problems. By the end of fiscal year 423/422 BCE, the Athenian debt to the sacred treasuries had reached 5,600 talents with an accumulated interest of 1,400 talents. Spartan victory in the war proved to be the final blow to Athenian hegemony, but Athenian banking concepts survived.

Banking in the Hellenistic World: Ptolemaic Egypt

When Alexander the Great died in 323 BCE, his empire was divided by his generals into several kingdoms, signaling the start of the Hellenistic Era. This period was marked by the spread of Greek art, language, and culture, which also included coinage, monetary theory, and banking. Greek-inspired banking and economics were perhaps the most evident in Ptolemaic Egypt.

Egypt was a fertile location for the adoption of Greek banking and monetary theories because it was home to preexisting advanced economic ideas. Egyptian documents show that from about 3100 BCE, Egyptians used weights and measures that functioned as a type of currency. In the 12th dynasty (c. 1985-1773 BCE), the Egyptians standardized these weights into an advanced proto-currency. The deben was a unit of measure that equaled about 93.3 grams, while a kite equaled slightly less than ten grams. One deben equaled ten kites. The deben was used as a measure of copper, silver, or gold, while the kite was used only to measure the more precious elements of gold and silver.

The second king of the Ptolemaic dynasty, Ptolemy II (ruled 284-246 BCE), was an active ruler who commissioned many public projects. Ptolemy II funded the construction of the Lighthouse of Alexandria and the Library of Alexandria. A canal that linked the Red Sea to the Mediterranean Sea was also built during Ptolemy II’s rule. These ambitious projects were expensive and required sound monetary and banking policy to fund them.

Ptolemy I (ruled 302-282 BCE) introduced coinage to Egypt, which was based on the drachma used throughout the Greek world. Due to a lack of silver mines in Egypt, the Ptolemaic drachma weighed less than other drachmas, and those used internally were mostly bronze. This facilitated person-to-person transactions. The amount of bronze coins circulating greatly increased during Ptolemy II’s rule, partially due to the requirement to pay taxes with coins. The ubiquitous yet cumbersome nature of hard currency meant that a banking system was needed for the collection of taxes and the extension of credit.

Borrowing from the Athenian system, Ptolemy II introduced both state and private banks that were licensed and franchised by the crown, with at least one bank in the capital of every nome (province). Royal banks collected coin taxes, and both royal and private banks extended credit and loans to private individuals at the exorbitant interest rate of 24%. The high, fixed interest rate prevented the development of a credit and debt economy.

Early Roman Banking

At the same time that the Ptolemies were refashioning Egypt’s economy to more closely align with that of the Greek world, the Romans were initiating their own banking and monetary changes, also drawing inspiration from Greek precedents. They also connected their banks to their gods, with the main aerarium, or public treasury, first established below the Temple of Saturn on the Capitoline Hill.

The first Roman silver coins were probably minted by the Roman state to commemorate the completion of the Via Appia from Rome to Capua in 312 BCE. Instead of using the widespread drachma as a currency standard, the Romans created the silver denarius as their standard coin. In addition to the denarius, the Romans also minted the sesterce, which was a bronze coin. Four sesterces equaled one denarius, and below that was the copper as, four of which equaled one sesterce. As the medium of the three denominations, the sesterce was the most commonly used coin for peer-to-peer transactions. Roman coins were technically worth their weight in silver, bronze, or copper, but the state did hold large amounts of gold.

Romans generally considered banking a lowly profession on par with acting. They considered making money from interest on loans an unworthy profession. Not all Roman banks and bankers profited from interest, but it appears that several did. Many utilized relatively modern monetary policies such as fractional reserve banking. This simply means that banks lend a portion of their reserve for interest. Roman records show that loans were referred to as a nomen or nomina (name), as they referred to the names of the debtors.

Roman banks were structured similarly to the Ptolemaic model, with the state bank having a monopoly on minting but also allowing private bankers. Banks and bankers were further divided into two primary categories by function. The faeneratores were moneylenders who functioned more like modern brokers and intermediaries, while argentarii were similar to traditional bankers.

Expanding Imperial Banking

The 1st century CE Roman biographer Suetonius wrote that two of Rome’s illustrious emperors had bankers in their families. Rome’s first emperor, Augustus (ruled 27 BCE-14 CE), had a grandfather who was described as a “money-changer,” possibly a faeneratore. One of Vespasian’s (ruled 69-79 CE) grandfathers “later turned banker among the Helvetii.” Despite general snobbery, familial connection to banking did not inhibit their rise to power.

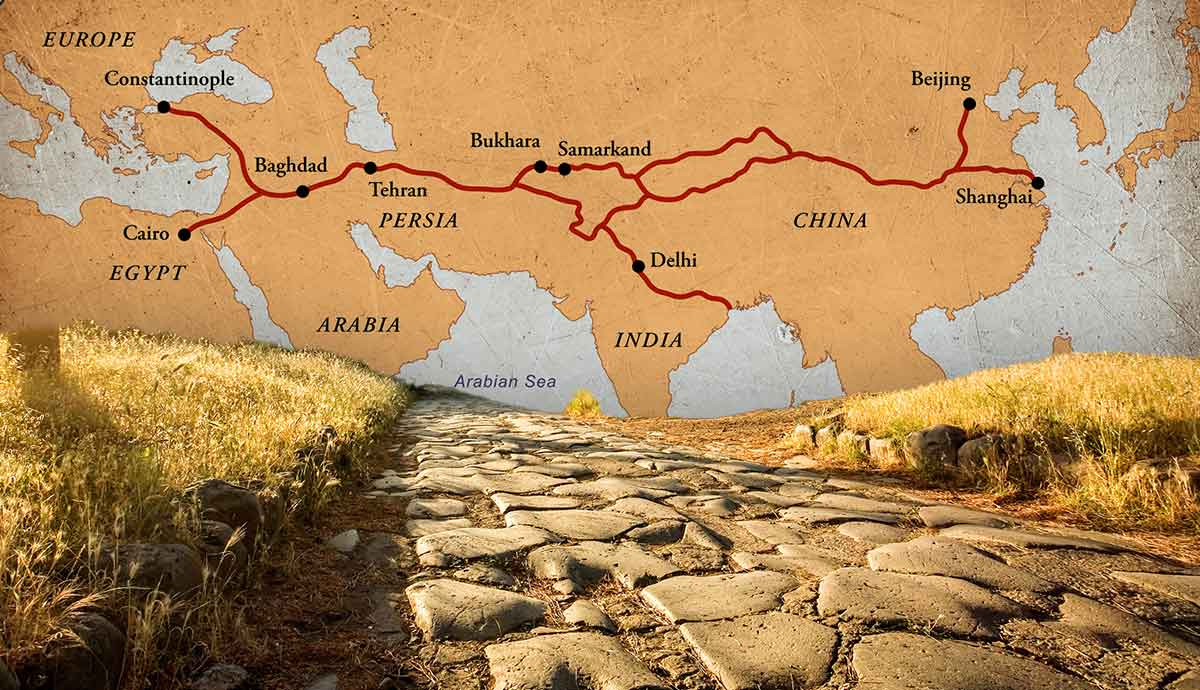

As the Roman Empire expanded, so did its banking. Many more denominations emerged, including gold coins such as the aureus, worth 25 denarii. Mints were also set up around the Empire to administer finances in Roman provinces and produce coins that transmitted central propaganda. Surviving records suggest that banking practices became heterogeneous across the Roman world, with Italian inscriptions and Roman Egyptian papyri records suggesting widespread integration of financial practices. Notably, public and private banks issued promissory notes that supported long-distance transactions.

The Collapse of Roman Banking

Rome faced many of the challenges of modern banking, including inflation. When the denarius was first introduced, it weighed nearly 4.5 grams of pure silver. It remained at that weight until the end of the Republic. During the early Empire, it stayed stable at around 4 grams, but at the accession of Nero (ruled 54-68 CE), it was reduced to 3.8 grams. This marked the start of continuous debasement. By the early 3rd century CE, the denarius had fallen to less than 50% purity.

Diocletian reaffirmed the denarius at 3.8 grams of silver at the start of the 4th century, but economic collapse continued. Heavy military spending and imperial policies undermined the economy. For example, maximum prices were established for specific commodities, which led to product scarcity and financial ruin for merchants. At the same time, the ascent of Christianity led to restrictions on banking as charging interest was seen as immoral. Consequently, banks mostly collapsed during the 3rd and 4th centuries CE. Organized banking all but disappeared until the Crusades, when the Knights Templar led the rise of a new approach to banking.