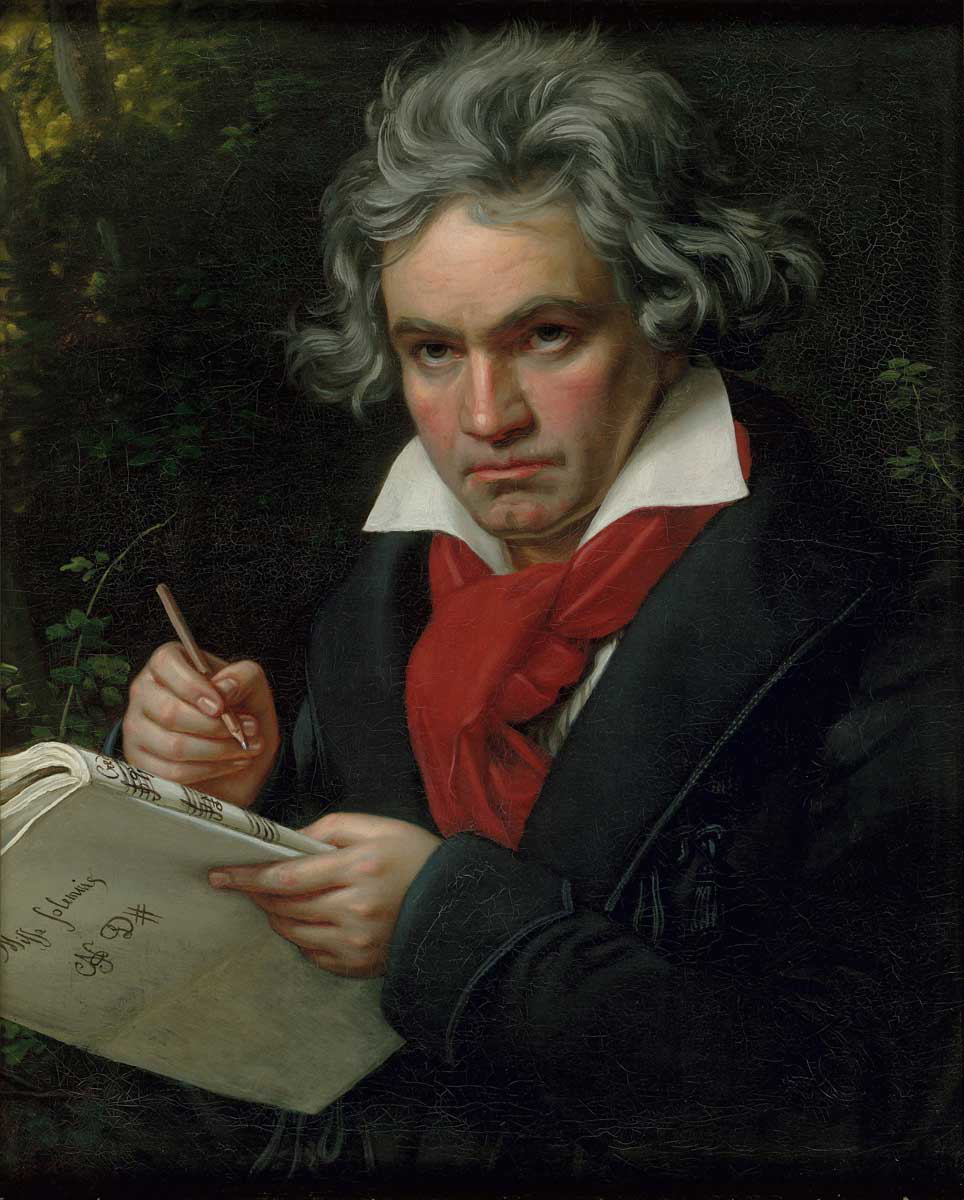

Beethoven’s nine symphonies stand out as towering giants in the symphonic world. From the humble beginnings of the First Symphony composed in 1800 to the gravity-defying Fifth Symphony (1808) to his ninth and final symphony (1824), each offers listeners a unique soundscape. He constantly pushed the boundaries of the symphonic form—as laid down by his predecessors, Haydn and Mozart—with revolutionary ideas. Beethoven would set the bar for nearly 200 years.

Beethoven’s Five Most Influential Symphonies

The symphony is a light-hearted composition with one aim in mind — to entertain the audience. But it is not a slapstick, roll-on-the-floor-laughing comedy either. The Rococo Period flowed into the Classical Era and the focus now was on balance, harmony, established forms, and the rise of ensembles like the string quartet.

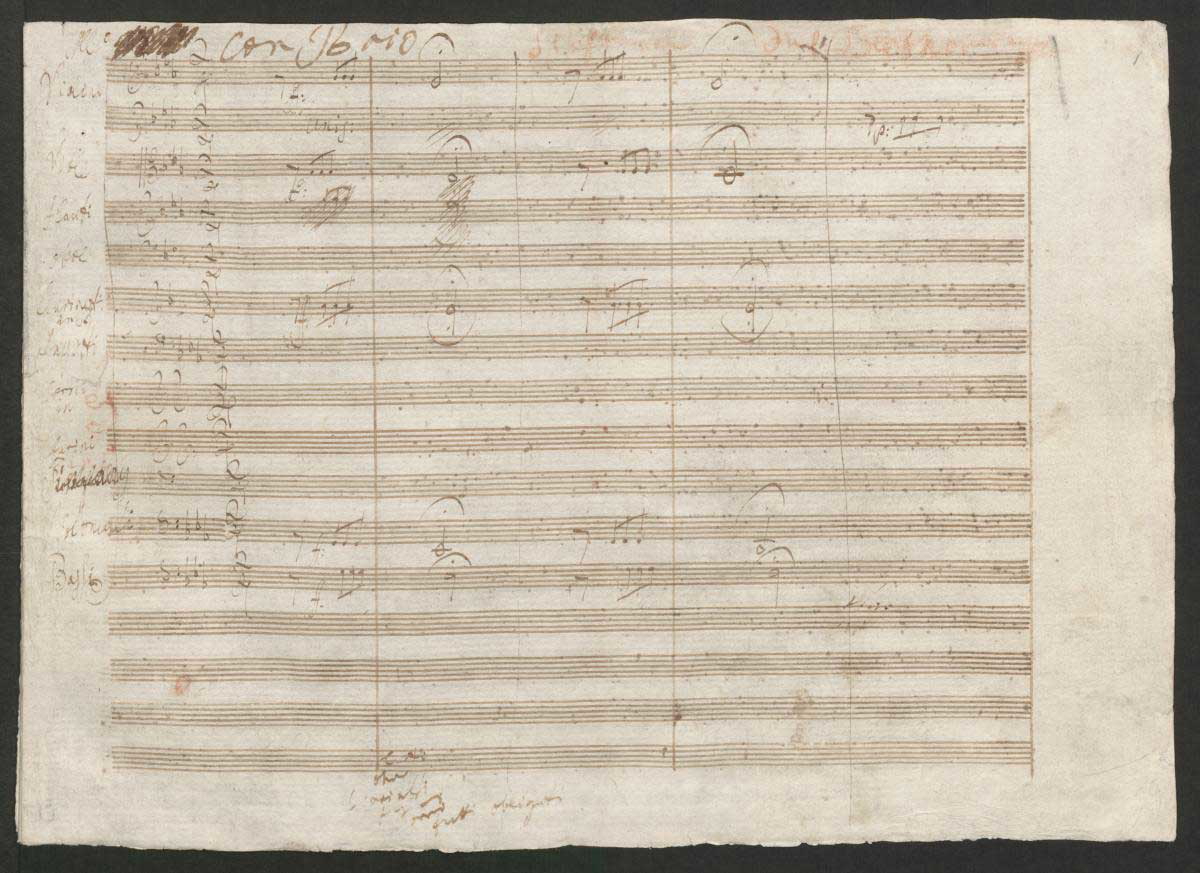

While I would love to write an exhaustive guide to each symphony, it is nearly impossible. I will highlight the most important features of five of Beethoven’s most influential symphonies and link exciting resources for each one that contains a wealth of information. A summary of each is presented to help you understand and hear the most salient parts before diving into the individual movements.

1. Symphony No. 1 in C Major, Op. 21 (1800)

The Beethoven we’re all used to—bold and loud—is not all-out present yet. Beethoven’s First Symphony is very much in the Classical style set out by his mentor, Franz Joseph Haydn, and his contemporary, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. Yet, there are hints of his later style: quick changes in the dynamics and experimentation with harmony and form are already present.

From the outset in the first movement, Beethoven “upsets” the natural order of the Viennese Classical tradition. He announces his arrival rather dramatically. But he is also cautious and does not stray too far from the established norms of the Classical symphonic mold.

Notable influences Beethoven copied and adapted for his First Symphony include:

- Mozart’s Symphony No. 41 in C Major, ‘Jupiter’, KV 551 (1788)

- Haydn’s Symphony No. 97 in C Major, Hob. I/97 (1792)

Instead of opening in the tonic (home) key, he opens with a sequence of dominant seventh chords leading away from the tonic key, C major. It is as if the music is indecisive, it cannot settle on the right key signature. But suddenly, the tonic key, C major, is established (at 01:17). Instead of leading the music towards the dominant (fifth note), the listener is confronted with it when the oboe, followed by the flute, announces the second thematic subject in the dominant (at 02:03). This is a technique Mozart often used as a joke and now Beethoven copies it, too. The theme is “passed around” the orchestra but soon enters a darker territory with woodwind writing reminiscent of Mozart.

It is like sunshine breaking through on a cloudy day when the recapitulation returns (at 06:27) in a dramatic fashion somewhat out of place in the Classical idiom. But this is Beethoven after all… A short transition (between 08:08 and 08:20) leads to the loud and bombastic coda (08:21).

The second movement (starting at 09:15) brings some respite from the fierce and fast first movement. Again, the sonata form is used like the first movement. The Violin II opens with a theme reminiscent of a stately dance and uses fugal imitation as the melody is imitated by other groups of instruments throughout the orchestra. Of note is the importance of the timpani during this movement — usually it is associated with military or funeral music. The timpani’s entry (at 10:36) is unusual in a slow movement, yet it is a clear calling card on Beethoven’s part of things to come.

The third movement (starting at 16:10) is Beethoven’s individuality shining through at its brightest. Although it is labeled as a Menuet (a stately court dance), it is a Scherzo or “joke.” It is only a Menuet on paper to keep with the expectations of the Classical Era. The tempo is too fast to dance to, and irregular phrases and displaced accents all add to the joking nature of the movement. Beethoven inherited this idea from Haydn who increasingly started to move away from the slow third movement expectation in his string quartets. Apart from the boisterous opening, the Trio section takes a slightly slower tempo with woodwind chords dominating (at 17:38) but quickly the opening theme returns softly (at 18:40) to dominate the scene.

Again, Beethoven deviates from his predecessors by adding a slow introduction to the fast, final movement. What is more, Beethoven wrote a masterful orchestral joke — the first violins try to reach a full octave, but constantly fail. With each “attempt,” the music swells from soft to loud but falls back to soft and creates a sense of tension and ambiguity. With each repeat, the violins try to fit more notes into the passage to reach the octave but fail. The joke is excellently portrayed by the violinists in the accompanying video above between 19:27 and 19:48.

At last, the orchestra joins in, and the theme is completed and transforms the hesitant theme into a driving scale-like passage, in the style of Haydn and Mozart in sonata form. At last, the listener is introduced to the home key of C major. While the Timpanis were quiet in the previous movements, they are now loud and proud and join the orchestra without hesitation.

2. Symphony No. 2 in D Major, Op. 36 (1802)

It is almost shameful that this symphony is frequently overshadowed by the First and Third Symphony because the work’s “bold, inspired, and adventurous spirit …foreshadows Beethoven’s heroic style and new symphonic vision that would take full flight in the monumental Eroica Symphony” (Eastman School of Music, 2024).

Again, Beethoven looks to Haydn and especially Mozart in acknowledgment and for inspiration and finds it in Mozart’s Symphony No. 38 in D major, K. 504, nicknamed the Prague Symphony. Similarities include the lengthy introduction, colorful writing especially the woodwinds, and frequent shifts between major and minor tonalities. It is written in sonata form with a long introduction.

The introduction (00:36-03:10) is three times as long as that of Symphony No. 1, lasting almost three minutes and marked Adagio molto (very slow). It contains a myriad of ideas, melodies, and phrases that could have been developed into a slow movement on its own. Instead, he dives into the exposition’s first theme (03:10-03:59) with a nervous fluttering in the strings taken up by the rest of the orchestra moments later. It grows in intensity until it gives way to the second theme (04:00-04:39) which is (probably) based on a French march he purloined and put into his symphony. However, the second theme departs from calmness to a dramatic treatment leading into the development section (04:39-06:59).

Finally, the recapitulation takes place with the first subject’s upward surges in the strings (07:04-08:53). An unusually long coda (08:54-10:07) is added to the end in a majestic style unprecedented in Classical symphonies until now.

The second movement (starting at 10:26) brings a welcome respite from all the drama and majesty of the first movement. The second movement demonstrates Beethoven’s move towards the Romantic Era through the emotional depth, intimacy, and introspective nature of the movement. It is also written in sonata form. There are two quotable moments in the exposition which I will touch upon briefly. The intimate opening reminds one of string quartet writing (10:27-11:16) repeated by the winds. There is also a Mozartian moment that reminds one of Mozart’s wind serenades (11:18-11:52) with a call-and-response between the winds and strings during the latter part.

The third movement is a lively scherzo instead of a graceful minuet. It recalls the energy of the first movement through its fast tempo, and frequent shifts in dynamics, and bounces the musical themes around the various groups of instruments. It is a rounded binary form: Scherzo (20:29), Trio (22:16), Scherzo (23:12). We could describe this movement as a celebration of life’s joys.

The final movement is marked Allegro molto (starting at 24:17) and is in a sonata rondo form with an extended coda. The opening sounds like a hiccup or stumble followed by trill-like laughter (24:17-24:27).

2. Symphony No. 5 in C minor, Op. 67 (1808)

“Thus, Fate knocks at the door!” Beethoven (allegedly) proclaimed to his assistant Anton Schindler (who had a habit of embellishing facts slightly). The opening four notes are perhaps the most famous four notes in music history. John Elliott Gardiner explores some of the possibilities that there are hidden messages woven into the score encapsulating the beliefs and values of the French Revolution.

The writer ETA Hoffman praised the Fifth Symphony as one of the era’s most important works while highlighting the “fate motif” as a symbol of Beethoven’s struggle with his deafness and personal turmoil.

The main four-note theme pervades the first movement (starting at 00:01) with its sense of urgency and inevitability throughout. We can consider it as the building block of the whole symphony — a single sentence that expands into whole musical paragraphs. It can also be interpreted through a Romantic Era lens as the individual hero facing the onslaughts of the larger world. The horns mimic the opening motif introducing the second subject (at 00:40).

Although it is a more lyrical treatment, the sense of urgency is ever present in the underlying structure. The development section (starting at 02:36) uses texture, orchestral colors, and dynamics rather than harmony to drive the music forward. The development is reduced to a single orchestral voice with a call-and-response exchange between the woodwinds and strings (between 03:18 and 03:49) before suddenly diving headfirst into the recapitulation at 03:50. The movement is ended by the tumultuous and stormy developmental coda (05:19 to 6:40) ending the movement in the same way it began. A heroic resolution is deferred until later.

Despite all the dramatic twists and turns, Beethoven balances all the sections of the first movement perfectly — each section is between 123 and 129 measures long.

The slower second movement (between 06:49 and 15:22) brings some welcome respite from the fireworks heard in the first movement. Two themes, each with its own set of variations are introduced. The first theme is played by the violas and violoncellos (06:49-07:40) and the second is introduced by the woodwinds (at 07:41). Suddenly, the theme erupts in a triumphant march (at 07:53). After these two themes are introduced, the listener is taken on a journey through various variations in major and minor key signatures. The goal of moving from the darkness of C minor set out in the first movement towards C major is nearly attained, but Beethoven delays the triumph again.

The low strings introduce a mysterious theme (15:30) repeating it twice before the horn enters with the fate motive as if it is a call to action (at 15:49). Although the third movement is not labeled as a Scherzo it features elements of the Beethovenian scherzos found in the previous symphonies: a quick tempo, misplaced accents, and differing phrase lengths.

The Trio (17:06-18:20) does not feature the typical pastoral elements with a focus on the woodwinds but erupts in a fugue in C major. The fugue adds seriousness to the third movement and continues the C minor/C major struggle. After a downward motion in the low woodwinds continuing in low strings (18:16), the Scherzo theme is taken up again by the orchestra at 18:20. The fate motive is used in the timpani (22:17) as a final expressive gesture and acting as a bridge to the final movement, which commences without a pause.

In the last movement (starting at 22:49) the symbolic hero finally triumphs over all his obstacles. Beethoven features instruments like the piccolo, contrabassoon, and trombones that did not make up the standard symphony orchestra of the time.

During the exposition, four major key themes are introduced while the development (26:33 to 28:45) section revisits ideas from the Scherzo. Using this cycle of harking back to previous material reminds the listener of the hero’s struggles and his ultimate triumph in the recapitulation (28:45). The coda (31:07 until the end), Beethoven’s longest until now, is written entirely in C major. Beethoven increases the tempo, driving the movement to its final, triumphant close. The hero emerges victorious despite all the struggles and the symphony ends with a unison C major chord ringing out.

3. Symphony No. 7 in A Major, Op. 92 (1812)

The Seventh Symphony marked Beethoven’s return to the symphonic form after a three-year break.

The standout feature of the first movement is the lengthy, slow introduction (0:03-03:50) which some scholars suggest may be considered as a separate movement altogether. The transition to the sonata form, which forms the actual movement, is signaled by a simple rhythmic pattern in the oboe and violins (between 03:50 and 03:55). This rhythm shapes the rest of the movement and moments of silence (between 08:23 and 08:33) are used to create anticipation and changes in the material. The development section (08:34-10:32) follows the two blaring silences. The recapitulation (10:33-12:58) introduces new tonal centers and has a different feeling altogether. The blaring silences are used again to section the coda (12:59-14:19) off on its own.

The second movement, starting at 14:44 and lasting until 24:06, is a melancholic, rhythmically driven movement. It has captivated audiences since its premiere in 1813. Early audiences often demanded an encore of the movement before the rest of the symphony could be played! This movement’s appeal lies in Beethoven’s ingenious combination of simple melodic lines, the driving rhythm that pervades the movement, and unexpected harmonies. It invites listeners on a haunting aural journey that fuels the imagination.

This symphony’s third movement features the longest Scherzo Beethoven had composed up to this point (the Ninth Symphony’s would exceed its length). Typical Scherzo features include irregular phrases, playful rhythms and misplaced accents, humorous insertions, and a surprising ending. One could compare the Scherzo (starting at 24:30) to horses galloping and frolicking. The Trio (26:57) may have been inspired by an Austrian folk tune and brings some respite from the Scherzo’s boundless energy.

The final movement (at 34:08) dramatically shifts away from the Scherzo. The rhythmic vitality of the movement coupled with its exuberance, can be described as a bacchanalian whirlwind of musical energy. The movement is composed in a sonata rondo form filled with complex rhythms and energetic themes. The coda (at 39:12) is a wild ride until the end is filled with energy and exploration of different key signatures and ideas. For the first time in Beethoven’s compositional career, he uses a triple forte marking (fff, forte fortissimo, as loud as possible or extremely loud), too.

4. Symphony No. 9 in D minor, Op. 125 “Choral” (1824)

The “Choral” Symphony is perhaps Beethoven’s most-discussed and majestic symphony and is renowned for its cultural, political, and religious impact since its premiere in 1824. Its powerful message is based on Friedrich Schiller’s text, Ode to Joy, which celebrates human unity and joy. This is the only symphony from Beethoven’s late period. Beethoven was completely deaf when he composed his last symphony, which makes it even more remarkable. It breaks the mold of the classical symphony form in every aspect of the Classical symphonic form. It has towered over composers for nearly two centuries and inspired composers like Wagner, Mahler, Brahms, and Shostakovich, to name a few.

The opening of the first movement is unusual — it starts with a nebulous opening (00:43-01:07) sounding like an orchestra tuning before a performance rather than presenting a clear theme or direction. Yet, this is the first theme. I interpret this opening as the birth of the hero who will rise to their full glory in the final movement. For the first time in a symphony, Beethoven omits the repeat of the exposition and plows directly into the development section (05:54-08:38). The development section is tumultuous and emphasizes the idea of the orchestra struggling to find the “correct” key signature by swaying between A minor and A major.

Finally, the recapitulation (05:54-11:27) arrives with the first theme presented in D major rather than D minor and unresolved tension that will last until the last movement. This is a technique used in his earlier symphonies. This movement ends with a dramatic coda (11:28-14:36).

The second movement features two distinct musical ideas. First, the Scherzo (15:19-22:23) in a five-voice fugue written in sonata form in D minor. Second, the Trio (22:24-24:43) is written in D major and is joyful and light when compared to the seriousness of the Scherzo. The Scherzo returns (at 24:44) and sandwiches the Trio in the middle of the movement. For a moment, the listener might think the Trio is repeated (at 29:41-29:46) as with previous Beethoven symphonies. But, alas, the movement abruptly ends. Beethoven is having the last laugh here as he humorously snatches the movement away from the audience.

In the third movement, it is as if Beethoven pulls back and recedes into a slow, lyrical mood. It uses a double variation form, where two themes are introduced and presented in their varied forms throughout the movement. The first theme (30:58-32:44) is in B-flat major while the second is composed in D major (32:44-33:47). Beethoven explores these themes in different keys and guises, preparing the music for the triumphant last movement.

The Finale is perhaps the most famous part of the whole symphony and certainly the most well-known too. Like the Third and Fifth symphonies, this symphony deals with stepping out of the darkness and entering the light. Finally, the hero will attain their goal and joy.

The last movement (42:50-42:59) begins with a dissonant chord resembling the hero’s struggle by symbolizing it through the orchestra’s struggle to settle on a key signature. Perhaps “Horror Fanfare” is the best way to describe this opening, which gives way to the cellos and double basses recalling material from the previous movements (at 43:10). Proleptic fragments of the “Joy Theme” are sprinkled into the mixture of recall-and-foreshadowing, setting the stage for the joyful resolution. A bass soloist “reprimands” (48:47-49:27) the orchestra with Beethoven’s snippet of text: “O friends, not these tones! Rather, let us tune our voices more pleasantly, and more joyously.”

After the bass soloist’s reprimand, the Ode to Joy (49:29-01:04:05) is presented in a theme-and-variation form. Each of the six variations, based on Schiller’s text, increases in complexity. Themes like human friendship, divine joy, and nature’s gifts are explored in the orchestra through rhetorical gestures to strengthen the choir’s message.

Beethoven adopts a theme from Mozart’s Misericordias Domini K. 222. In Beethoven’s time, adapting a melody from another composer was not seen in the same serious light as we view plagiarism today — it was a form of flattery and homage to the original creator. Brahms also purloined the theme from Beethoven (or was it Mozart?) in the final movement of his Symphony No. 1, Op. 68 (1862–76). As a final triumphant gesture, and showcasing his brilliance as a composer, the sixth and final variation is a double fugue (59:11-01:04:03). In this double fugue there is the “Joy” theme strophe from Schindler’s text, and the two second-last strophes. The combination of these three elements symbolizes the pursuit of the creator and all mankind living in harmony to achieve true joy.

In a rousing “double” coda, the symphony is ended. The “first” coda (01:04:05-01:05:25) belongs to the choir along with the full orchestra. Beethoven reaffirms that all people (alle Menschen) will find joy in the “Divine Spark” (Gotterfunken) given by the loving Father who dwells above the stars. The orchestra drives the music to the end in the “final” coda (01:05:25-01:05:43).

Final Thoughts

Beethoven was aware of the expectations of the audience in Vienna, but he also had a mind of his own and offered them a glimpse of the symphony’s future in his hands. He certainly had some unconventional ideas and throughout his career, he would singlehandedly change the course of classical music. While his first symphony is still conservative it paved the way for his “heroic” style seen in the later symphonies that would change the course of the symphony. For nearly two centuries, composers looked to Beethoven as their muse and an inspiration to look up to and try and emulate.

Further Reading and Listening

Dunnett, B. (2019, January 29). Sonata form. Music Theory Academy. https://www.musictheoryacademy.com/understanding-music/sonata-form/

Feld, M. Beethoven’s Symphony #9 (1824). (n.d.). http://www.columbia.edu/itc/music/modules/summa3/summa3_print.html

Boxwood&Brass. (2017, March 31). Natural Horn Demonstration – Anneke Scott [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fk9RmouFQik

Storm and Stress – New World Encyclopedia. (n.d.). https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Storm_and_Stress

Monteverdi Choir and Orchestras. (2020a, May 29). Symphony No. 3 “Eroica”: Heroism & shock tactics | Gardiner and the ORR on Beethoven’s Symphonies [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Io91Hvh4XvQ

Monteverdi Choir and Orchestras. (2020b, June 5). Symphony No. 4: Composing for all eternity | Gardiner and the ORR on Beethoven’s Symphonies [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MZWbCNNn6PI

Monteverdi Choir and Orchestras. (2020c, June 19). Symphony No. 6: Pantheism and camaraderie | Gardiner and the ORR on Beethoven’s Symphonies [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2nUfPBIRb48

Monteverdi Choir and Orchestras. (2020d, June 26). Symphony No. 7: Dithyrambic abandon | Gardiner and the ORR on Beethoven’s Symphonies [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8f0–cl1G4U

Monteverdi Choir and Orchestras. (2020e, July 3). Symphony No. 8: A tribute to Haydn | Gardiner and the ORR on Beethoven’s Symphonies [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2G_DrkWDi9o

Monteverdi Choir and Orchestras. (2020f, July 10). Symphony No. 9: “Up above the stars he must dwell” | Gardiner and the ORR on Beethoven’s Symphonies [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=riTOSWNI2pk

Ruhling, Michael E. Symphony No. 9 in D minor, Op. 125 “Choral” (1824) – Beethoven Symphony Basics at ESM – Eastman School of Music. (n.d.). https://www.esm.rochester.edu/beethoven/symphony-no-9/

Sus, Viktoriya. (2023, January 28). What Is the Ideal World? 5 Utopias Proposed by Famous Philosophers. Retrieved from https://www.thecollector.com/what-is-the-ideal-world-according-to-famous-philosophers/