Although literature is ever-changing, its capacity to provoke controversy is a tale as old as time. Literary trends may come and go, but the reasons a book might be deemed obscene remain pretty much the same. While the medieval and early modern periods saw numerous attempts by church and state to suppress material that was either blasphemous or lascivious, obscenity trials gathered pace in the 19th and 20th centuries, with the rapid growth of publishers who disseminated these books—and of legal systems that punished them for it.

1. D.H. Lawrence, Lady Chatterley’s Lover

Possibly the most famous obscenity trial in literary history, D.H. Lawrence’s last novel caught the attention of judge and jury in 1960, three decades after the author’s death. This was not Lawrence’s first brush with the law: in his lifetime, he had seen his novels Sons and Lovers, The Rainbow, and Women in Love come under attack for their frank representations of sex.

Lady Chatterley’s Lover may have been partly inspired by E.M. Forster’s novel Maurice (written in 1913-14 but unpublished until 1971), which features a relationship between an upper-class man and a male groundskeeper. While Lawrence’s novel focused on a heterosexual couple, it retained the controversial cross-class elements and went much further in its descriptions of extramarital sex. The novel is about the eponymous Connie Chatterley’s affair with her groundskeeper, Oliver Mellors, and is notable for its liberal usage of certain four-letter words to describe their acts.

Initially published privately in Italy in 1928, Lawrence’s novel was finally published in Britain in 1960 by Penguin Books, when it fell victim to an act introduced just a year earlier—the Obscene Publications Act 1959, which was, in fact, intended to promote a more liberal attitude towards literary censorship. As it turned out, the trial of Lady Chatterley’s Lover bore out the new act’s purpose to allow publishers to avoid conviction if the book in question could be proven to have literary merit. (This was how obscenity trials were judged in America, as we will see below.)

Following a six-day trial featuring various defense witnesses, including Forster and the critic Raymond Williams, Penguin was found not guilty of publishing Lady Chatterley’s Lover. The publisher brought out a second edition in 1961, and its instantly widespread readership testified to the public’s curiosity to encounter Lawrence’s unabashedly explicit writing.

2. James Joyce, Ulysses

For over a decade after James Joyce published Ulysses, readers in America could not get hold of the novel unless they could afford a trip to Paris, where expatriate Sylvia Beach—founder of the bookstore Shakespeare and Company—had issued it. Joyce’s seminal modernist novel fell victim to the United States’ 1873 Comstock Act, forbidding the circulation of obscene material via the US Post Office before it had even been published in full.

The Little Review, an avant-garde publication founded by Margaret Anderson and Jane Heap with the help of Ezra Pound (and one of the many “little magazines” that flourished in America in the modernist era), had been serializing Ulysses since 1918. But in 1921, the Post Office seized copies of the latest edition. This came as no great surprise to the editors: they had previously faced criticism and even obstacles to further distribution of the magazine for their willingness to publish material that criticized the war and promoted anarchism.

In particular, the extract from Ulysses titled the “Nausicaa” episode attracted attention because it seems to describe–in a shifting narrative style which makes it difficult to discern whose perspective we are viewing things from–how a young woman, Gerty MacDowell, titillates the protagonist, Leopold Bloom, to the point of orgasm. The trial in February 1921 aimed to determine whether this description might corrupt readers, especially young female ones. However, the focus soon shifted to the question of whether Joyce’s prose was even intelligible enough to corrupt anyone.

Jane Heap, editor of The Little Review, felt that Ulysses was on trial more for the challenge its style posed to literary conventions than for any real obscenity. As she wrote of the allegedly lascivious passages involving Gerty and Bloom: “Girls lean back everywhere, showing lace and silk stockings […] men think thoughts and have emotions about these things everywhere […] and no one is corrupted.” During the trial, both the defending lawyer and one of the judges admitted that they could hardly make sense of the novel, the latter comparing it to “the ravings of a disordered mind.”

The Little Review editors were ultimately banned from publishing any further material from Ulysses. Although the novel was finished in 1922 (when Beach published it in Paris), it did not appear in America until 1933, when the judge in the case United States v. One Book Called Ulysses ruled—in a landmark for literary freedom of expression—that the novel’s sexual material was not intended to promote lust, and therefore was not obscene.

3. Rose Allatini, Despised and Rejected

One of the lesser-known books on this list, Despised and Rejected, was published in 1918 under the pseudonym A.T. Fitzroy. Its author, Rose Allatini, was Austrian by birth but moved to London in her early twenties. She was married for a short time to the English composer Cyril Scott, but after they separated, Allatini spent the remainder of her life with a female partner. This gives an indication of why her novel might have caused outrage, like the other books in this list dealing explicitly with same-sex relationships—but this is only part of the story of the controversy around Despised and Rejected.

Written during the First World War, Allatini’s novel contains a host of characters who condemn the conflict, especially conscription. One of its protagonists, Dennis, is a conscientious objector who makes a series of eloquent speeches against the state forcing young men to become soldiers, speeches which are well received by his bohemian circle which (similar to the real-life Bloomsbury Group) included not just pacifists, but artists and writers, and couples living in unconventional arrangements such as same-sex partnerships. The novel’s female protagonist, Antoinette, initially falls for a mysterious older woman before meeting Dennis, who entertains the idea of a relationship with Antoinette in the hopes it might distract from his homosexuality.

Allatini sent her manuscript to the publisher Allen & Unwin in 1918 and (in an echo of the novel’s biblical title) it was rejected. But this was not solely because of the novel’s sympathetic treatment of homosexuality: after all, Allen & Unwin had, just two years previously, published My Days and Dreams, an autobiography by the gay activist Edward Carpenter. What Unwin balked at in Despised and Rejected was the combination of candid sexuality and pacifism at a time when Britain was still at war. He recommended Allatini send the novel to C.W. Daniel, a publisher committed to bringing out pacifist material.

When the book came out, journalist James Douglas agitated for it to be banned, deeming its “hideous immoralities” too terrible for comment and focusing largely on its dangerous promotion of conscientious objection. Following a trial at which Daniel was ordered to pay a fine, the publisher defended himself as regards the homosexuality—saying he had not noticed any possible “immoral interpretation” of the relationships in the novel—but he stood by its pacifism.

4. Radclyffe Hall, The Well of Loneliness

Ten years after his campaign against Despised and Rejected, James Douglas took to the pages of the Sunday Express to mount another campaign. This time, he urged for the suppression of Radclyffe Hall‘s novel The Well of Loneliness on the grounds of its sympathetic portrayal of lesbianism. Hall was not the only author to publish a book on this theme in 1928, which was something of a watershed year for lesbian literature: Compton Mackenzie’s Extraordinary Women (a satire about lesbian expatriate artists on Capri), Elizabeth Bowen’s The Hotel, Djuna Barnes’s Ladies Almanack, and Virginia Woolf‘s Orlando all came out in the same year. Bowen, Barnes, and Woolf escaped the censors by taking obscure or playful modernist approaches, while Mackenzie’s novel could hardly be said to promote the lifestyles it represents (its extraordinary women are, by and large, unhappy and unsuccessful in their relationships).

In contrast to Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover and Joyce’s Ulysses, The Well of Loneliness contains no explicit references to sex. Rather, it scandalized readers such as Douglas because its coming-of-age story of Stephen Gordon, a masculine lesbian who pursues relationships with women, presents Stephen’s homosexuality as an unchangeable fact of nature. Hall’s protagonist confronts theories that pathologize her identity as a criminal or medical condition but ultimately rejects this stigmatization and demands to be respected.

Douglas’s campaign was not roundly supported. Much of the British press approved of Hall’s plea for more tolerant (if still somewhat pitying) attitudes towards homosexuality. Nevertheless, the Home Secretary agreed that the book was dangerous and ordered its publisher, Jonathan Cape, to withdraw it. When Cape continued to covertly facilitate the novel’s distribution, the case came to court. A vast swathe of Britain’s literary elite mobilized to protest against suppressing the novel. However, not all took up the argument (not yet a legal necessity in the UK) that alleged obscenity should be permitted if the book had proven literary merit. Some, such as Woolf and E.M. Forster, were not overly fond of the novel on artistic grounds.

After a week-long trial, the judge dismissed the question of literary merit as irrelevant and ruled that the book was obscene. This led to another trial when Hall’s American publisher, Alfred A. Knopf, came to bring out The Well of Loneliness. Unlike in the UK, the US jury was obliged to consider literary merit and to focus only on the novel’s possible effect on adult readers, not children. Like the UK trial, the US trial brought together the biggest names in contemporary literature, with Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Edna St. Vincent Millay all taking the stand to defend Hall’s novel. Deeming that The Well of Loneliness treated lesbianism as a “delicate social problem,” the US jury cleared it of all charges. It was another two decades, however, before the novel could be circulated in Britain.

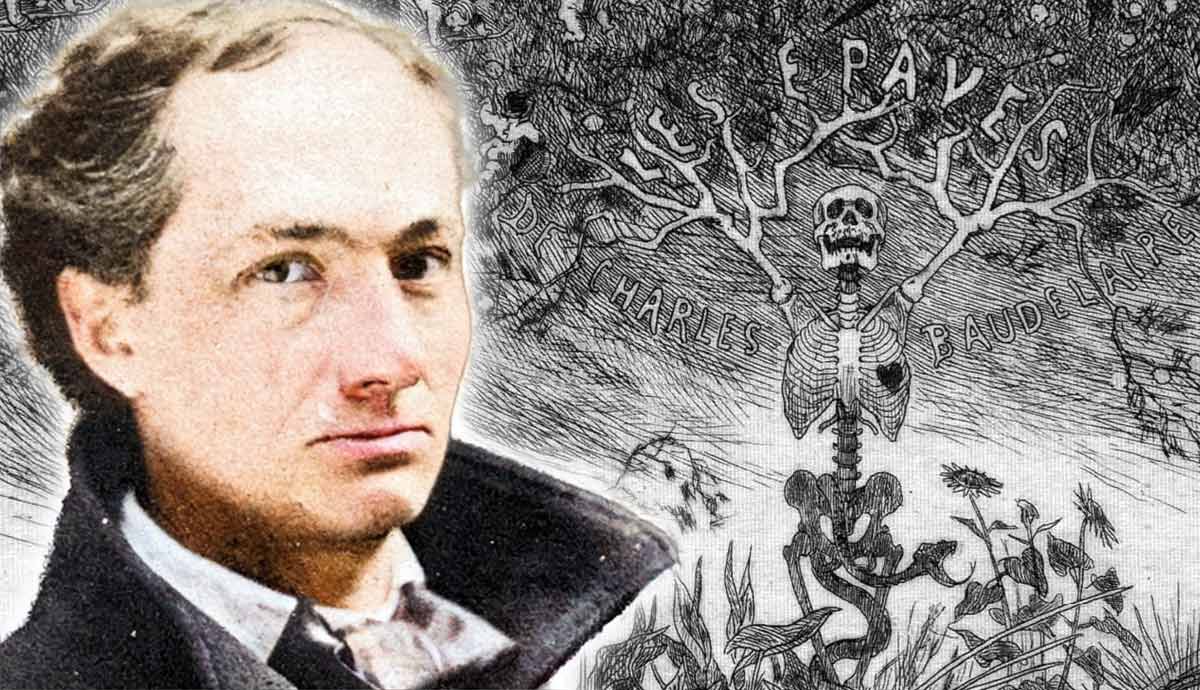

5. Charles Baudelaire, Les fleurs du mal

Some 70 years before Radclyffe Hall’s novel faced trial for a relatively sanitized depiction of relationships between women, Charles Baudelaire caused outrage in France for including poems about (among other things) lesbianism in his 1857 collection Les fleurs du mal (Flowers of Evil). Baudelaire’s book cemented the reputation he had been cultivating for the past decade as a poète maudit (literally, “accursed poet,” or one who lives outside the confines and comforts of polite society).

Les fleurs du mal not only contained poems touching on lesbianism but displayed Baudelaire’s fascination with what happens when sex, death, disease, the stench and screech of city life, and the sacred and profane combine. This heady brew and the relish with which Baudelaire crafted beautiful poetry on horrifying topics such as putrefaction and vampirism caused an outcry.

Under the regime of the Second French Empire, writers could be prosecuted for insulting public decency, and Baudelaire and his publisher were fined. They were also ordered to omit six poems from the collection (including”’Lesbos,” “The Vampire’s Metamorphoses,” and “The Damned Women”). Although this only whetted the appetites of many of Baudelaire’s fellow poets and artists, who celebrated his transgressive defiance of convention, these poems were left out of editions of Les fleurs du mal for nearly a century, when the ruling was finally overturned in 1949.

6. Walt Whitman, Leaves of Grass

While Baudelaire was submitting to the demands of the censors, across the Atlantic, another poetry collection by a poet eager to transcend ordinary society was causing a stir: Walt Whitman‘s Leaves of Grass, first published in 1855. The poems’ blend of Transcendental philosophy, comradely love between men, and simple, speech-like language and free versification outraged many readers. The abolitionist politician and author Thomas Wentworth Higginson wrote: “It is no discredit to Walt Whitman that he wrote Leaves of Grass, only that he did not burn it afterwards” (Broaddus, 1999, p. 76).

The book did find devoted readers, however, and something of a cult developed around Whitman. To his devotees, he was the prophet of a new, more democratic America, a vision he enunciated in the new poems that appeared in several new editions of Leaves of Grass over the next three decades.

In March 1882, Whitman’s publisher, James R. Osgood, received a request to remove certain poems from the collection on the grounds that they were obscene. The New England Society for the Suppression of Vice and their spokesman, Boston attorney Oliver Stevens, objected to poems that were sexually explicit (such as “To a Common Prostitute”), poems that expressed equal desire for men’s bodies and women’s (“The Sleepers,” “I Sing the Body Electric”), and poems which exposed the realities of pre-Civil War America (“Song of Myself”).

Although Osgood was prepared to comply with Stevens’s demands, Whitman was not. Anticipating that the scandal of attempted censorship would only increase interest in Leaves of Grass, Whitman took the book to a new publisher, and a new edition was brought out later in 1882. Its first printing sold out in one day (Reynolds, 1995, p. 543).

7. Allen Ginsberg, Howl

Beat poet Allen Ginsberg wrote Howl in 1954-55 after experiencing hallucinations under the influence of peyote. This background finds its way into the poem, with its horrifyingly riotous visions of the “best minds of my generation” all addled, in some way or another, “looking for an angry fix.” The poem name-checks peyote, benzedrine, nitroglycerin, and Metrazol; it offers vignettes of characters, taken from Ginsberg’s own experiences, “who copulated ecstatic and insatiate,” including pairs of men; it describes the whole in language which would, a few years later, come under discussion during the trial of D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover.

In 1957, two San Francisco booksellers—Shig Murao and Lawrence Ferlinghetti—were arrested for selling copies of Howl. As was the case for many of the books on this list, the prosecutors claimed it would be dangerous should children come across Ginsberg’s poem. As a 2010 film about Ginsberg depicts, the trial brought together a group of literary experts to defend the poem’s artistic merit and was overseen by a judge who had prepared for the case by investigating a pertinent legal precedent: the trial of Joyce’s Ulysses. Like that novel, Howl was judged to be treating its lascivious material artistically rather than with intent to provoke desire. Therefore, it was not obscene. Despite recurrent controversies surrounding broadcasts of Ginsberg’s poem, the obscenity trial did not damage its reputation but only enhanced it, making it an emblematic work of counter-cultural art.

8. Anthony Burgess, A Clockwork Orange

Although it was never the subject of a nationwide trial, Anthony Burgess’s 1962 novel has come into contact with the law on a number of occasions. The dystopian dark comedy was initially well received, although some readers found its depiction of gang “ultraviolence” distasteful. For the most part, though, audiences seemed able to distinguish between representation of a moral issue and endorsement of it (a perennially thorny question in literary reception—as Vladimir Nabokov, among others, found).

It was only when Stanley Kubrick adapted A Clockwork Orange as a film in 1971 that, much to Burgess’s chagrin, prosecutors began to object to the novel. The success of Kubrick’s film brought wider attention to its content, including scenes of rape and torture. Concerned about the domino effect of copycat violence in the real world, Kubrick withdrew the film from circulation in the UK in 1973. In the same year, a bookseller in Utah was prosecuted for selling A Clockwork Orange. Although the charges of obscenity were dropped, the incident was followed by the novel being banned in towns in Colorado, Connecticut, and Alabama in 1976, 1977, and 1982 respectively.

Even in 2019, the Florida Citizens’ Alliance urged for Burgess’s novel to be banned. Just last year, a school district in Texas banned A Clockwork Orange, although not for its depiction of violence. Instead, the book was deemed dangerous for “adopting, supporting, or promoting gender fluidity.” The days of censoring, banning, and even litigating against books are not yet behind us.

Further Readings:

Broaddus, Dorothy C. (1999). Genteel Rhetoric: Writing High Culture in Nineteenth-Century Boston. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press.

Reynolds, David S. (1995). Walt Whitman’s America: A Cultural Biography. New York: Vintage Books.