Born on September 11, 1885 in Eastwood, Nottinghamshire, David Herbert Lawrence was the son of a coal miner who defied the odds imposed on members of his social class to become one of the twentieth century’s most important writers. He was a pioneer of sex writing and was steadfast in his determination to challenge the taboo around writing sexual desire in literature. During his lifetime, he was beset by obscenity trials and his books were banned; upon his death, he was regarded by some as little better than a pornographer, albeit a man of great (though ultimately wasted) literary talents. Since the watershed obscenity trial of Lady Chatterley’s Lover in 1960, however, Lawrence’s work has re-entered the mainstream and his novels are now considered key canonical texts. Here, we will look at just five of his most notable novels, exploring the genius that informed them, and, in some cases, the controversy that dogged them…

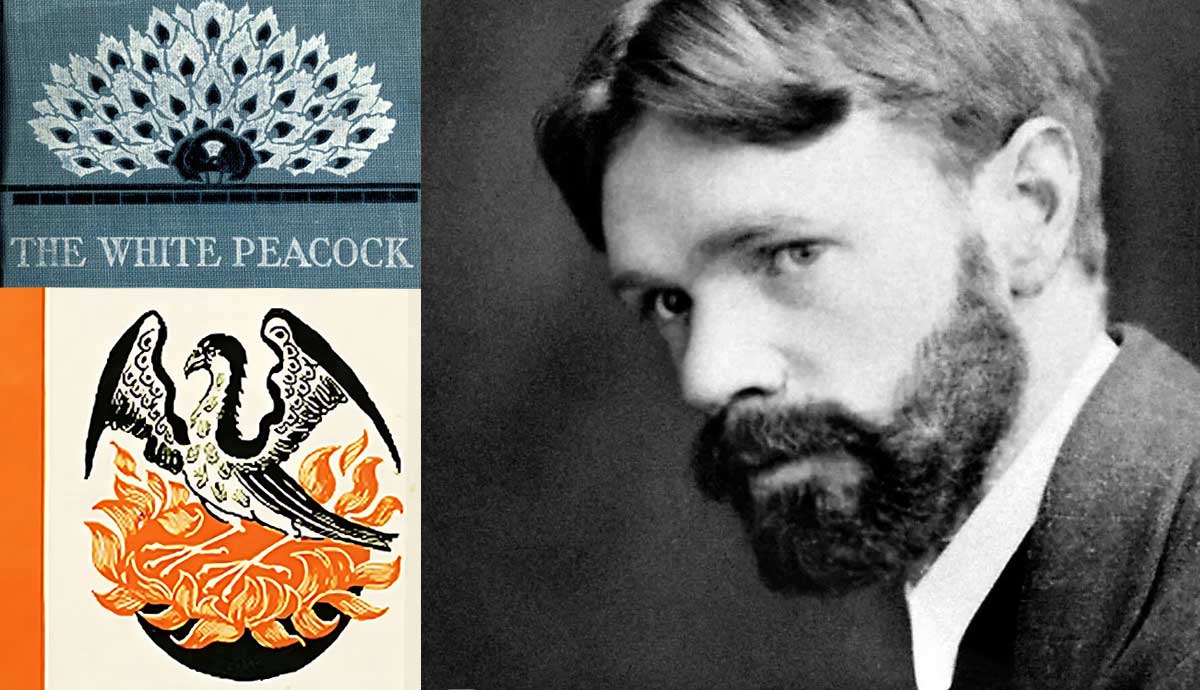

1. The White Peacock, 1911

The White Peacock, D.H. Lawrence’s first novel, came out in 1911, though it had a rather rocky road towards publication. Lawrence began work on the novel in 1906 and, during the four years it took to finish it, he rewrote it three times. Though he had made up his mind to become a writer even before graduating from University College Nottingham with his teaching certificate in 1908 (having won a short story competition in the Nottinghamshire Guardian in 1907), he was in no financial position to become a full-time writer.

And so, when he moved to London in 1908, he took up a teaching position at Davidson Road School in Croydon, while writing and immersing himself in London literary culture in his spare time. He was still working as a teacher when in 1910, while he was also working on The White Peacock, his beloved mother died of cancer. And, in the year The White Peacock was published, Lawrence himself suffered a severe bout of pneumonia, and it was only then that he became a full-time writer.

Get the latest articles delivered to your inbox

Sign up to our Free Weekly NewsletterThe White Peacock is one of Lawrence’s most notable novels, not least because it is his debut. Narrated by a character named Cyril Beardsall, it is written in the first person, which is atypical of Lawrence’s later novels. However, it explores many similar themes to his later works, such as love triangles, sexual desire, and, through his characteristically evocative descriptions of the natural world, the environmental impact of industrialization and the ambiguous division between city and country.

2. Sons and Lovers, 1913

Drawing on his own emotional turmoil following the death of his mother in 1910, Lawrence wrote Sons and Lovers, which was published in 1913. By the time it was published, however, Lawrence had tired somewhat of the novel, perhaps owing to the emotional labor required to write such a personal novel in the wake of his mother’s death. He therefore granted Edward Garnett (a writer, critic, and editor) carte blanche to cut a substantial number of pages from the manuscript, which he duly did. Despite Lawrence’s seeming indifference towards the novel, Sons and Lovers is now widely considered to be a literary masterpiece.

Telling the story of Paul Morel and his family, Sons and Lovers is both a family saga and a bildungsroman of sorts. At the center of the novel is the relationship between Paul and his mother, Gertrude, an educated and refined woman who is as frustrated in her marriage to a lower-class coal miner as she is devoted to her three children. Following the death of her eldest son, Paul – a sickly child, just as Lawrence himself was – becomes a particular pet of hers. The deep love that exists between mother and son, however, causes issues as Paul grows up and finds himself incapable of forming real long-term relationships with women, so does his love for his mother verge on a Freudian-style Oedipus complex.

Aside from this aspect of the novel, however, the publication of Sons and Lovers also marked a seminal moment in the history of the English novel. For the first-time, working-class lives were depicted by a working-class writer, who could capture both the struggles and the joys of life in a Midlands mining community.

3. The Rainbow, 1915

Published just two years after Sons and Lovers, The Rainbow is a family saga, charting the lives (and love lives) of three generations of the Brangwens across the 1840s to 1905 in Nottinghamshire. Against the backdrop of increasing industrialization, the novel moves from the life of Tom Brangwen, a farmer, to that of his granddaughter, Ursula, who attends university and goes on to work as a teacher. It is Ursula’s section of the novel that dominates, as she struggles to make her way and to find love in what would have been a near-contemporary society for Lawrence’s first readership.

In a bid to find a love that is both satisfying and meaningful, Ursula has a relationship not only with Anton Skrebensky (a British soldier of Polish heritage), but also a relationship with a fellow female teacher, Winifred Inger. In writing the latter, Lawrence drew inspiration from a same-sex relationship of Katherine Mansfield’s. Mansfield was a friend of Lawrence’s, though she was particularly close to his partner, Frieda, to whom she had confided the story of her illicit lesbian love affair in confidence. Frieda, in turn, relayed the story to Lawrence. And when Mansfield read The Rainbow, she was dismayed to find her own story fictionalized through the experience of Ursula. This betrayal colored her opinion of the novel as a whole, though she remained intimate friends with Lawrence and Frieda for the time being.

It was also as a result of Lawrence’s depictions of sexual desire (and, presumably, of homoeroticism in particular) that led to The Rainbow being tried for obscenity in the United Kingdom in 1915. As a consequence, over one thousand copies of the novel were confiscated and subsequently burned. It remained unavailable in the UK for the next eleven years.

4. Women in Love, 1920

In 1920, Women in Love – the sequel to The Rainbow – was published. Staying with the Brangwen family, it follows the love lives of Ursula and her younger sister, Gudrun. While Ursula is still working as a teacher, she gets better acquainted with Rupert Birkin, a school inspector and erstwhile intellectual closely aligned with Lawrence himself.

Gudrun, meanwhile, has returned home to Nottinghamshire from London, where she is an artist. Back home, she meets Gerald Crich, the wealthy heir to the local coal mine. While Ursula and Birkin’s relationship runs (relatively) smoothly, Gudrun and Gerald are locked in a battle of wills, and yet seemingly cannot stay away from each other. All of this builds to an explosive denouement, which has been described by Mark Schorer as having “all the force and pathos of the greatest novels, the real Russian bang” and therefore being one of the few instances of such a “bang […] in English fiction” (see Further Reading, Schorer, p. 46).

As with The Rainbow before it, Women in Love caused controversy. Although it was only available to subscribers in the UK due to the ban on The Rainbow, it nonetheless found its way into the hands of reviewers, some of whom took an unfavorable view of the novel. And, while Women in Love was not taken to court for obscenity, Lawrence was sued by Lady Ottoline Morrell (on whom the character Hermione Roddice was blatantly based) for libel. He had also based Gudrun on Katherine Mansfield, and Gerald on her long-term partner (and later husband) John Middleton Murry. Despite all these controversies, the novel is now considered a classic.

5. Lady Chatterley’s Lover, 1928

It is probably fair to say that, even today, Lady Chatterley’s Lover enjoys a somewhat infamous reputation. This is in spite of having been found not guilty of obscenity in the watershed trial of 1960, and in spite of the fact that other novels by Lawrence (as we have already seen) were also taken to court for various reasons. Nonetheless, it can be argued that some residual scandal still remains attached to Lady Chatterley’s Lover.

Published privately in Italy in 1928, Lady Chatterley’s Lover is said to be based on a number of different stories, including an affair between Lady Ottoline Morrell and a stonemason in her employ, and E.M. Forster’s novel Maurice, which remained unpublished until 1971 though Lawrence was among those who had seen the manuscript. (As the above examples of Lawrence’s novels attest, he often drew inspiration from his own life and from the lives of those around him, rather than imaginatively creating stories for his characters).

Just as Maurice focuses on homosexual love and desire and features a love affair between two men of different classes, Lady Chatterley’s Lover was considered so scandalous in part because it depicted a sexual relationship between an upper-class woman (the eponymous Connie Chatterley) and her gamekeeper (Oliver Mellors). This, in turn, feeds into the novel’s wider exploration of social class, as tensions between the Tevershall colliers and Sir Clifford Chatterley (the mine owner) simmer. However, it seems few readers at the time could have been trusted to look beyond the explicit depiction of a cross-class sexual relationship (and Lawrence’s use of certain four-letter words) to the wider thematic point about contemporary British class relations.

Connie Chatterley’s husband, Sir Clifford Chatterley, is paralyzed from the waist down due to an injury sustained during the First World War. Since he is left sexually impotent as a result, Connie embarks on an affair with Mellors. It is through this relationship that Connie comes to realize the importance of physical and sensual experience. Thus one of the themes of the novel (as argued by Richard Hoggart in the 1960 obscenity trial) is the need for greater cohesion between the mind and the body.

While D.H. Lawrence’s reputation may have been compromised by the controversies surrounding the publication of some of his novels by the time he died of tuberculosis in 1930, fellow novelist E.M. Forster, in writing an obituary of Lawrence, hailed him as the “greatest imaginative novelist of our time.” If a residual whiff of scandal and salaciousness is still associated with Lawrence’s work in certain quarters, his novels are also canonized as classics of early twentieth century literature and are – to this day – among some of the best works ever written.

Further Reading:

Schorer, Mark, “Women in Love and Death,” The Hudson Review, 6, 1 (1953), 34-47.